.22-250 Improved

Higher Velocity Handloads in a Sisk STAR Rifle

other By: John Haviland | February, 26

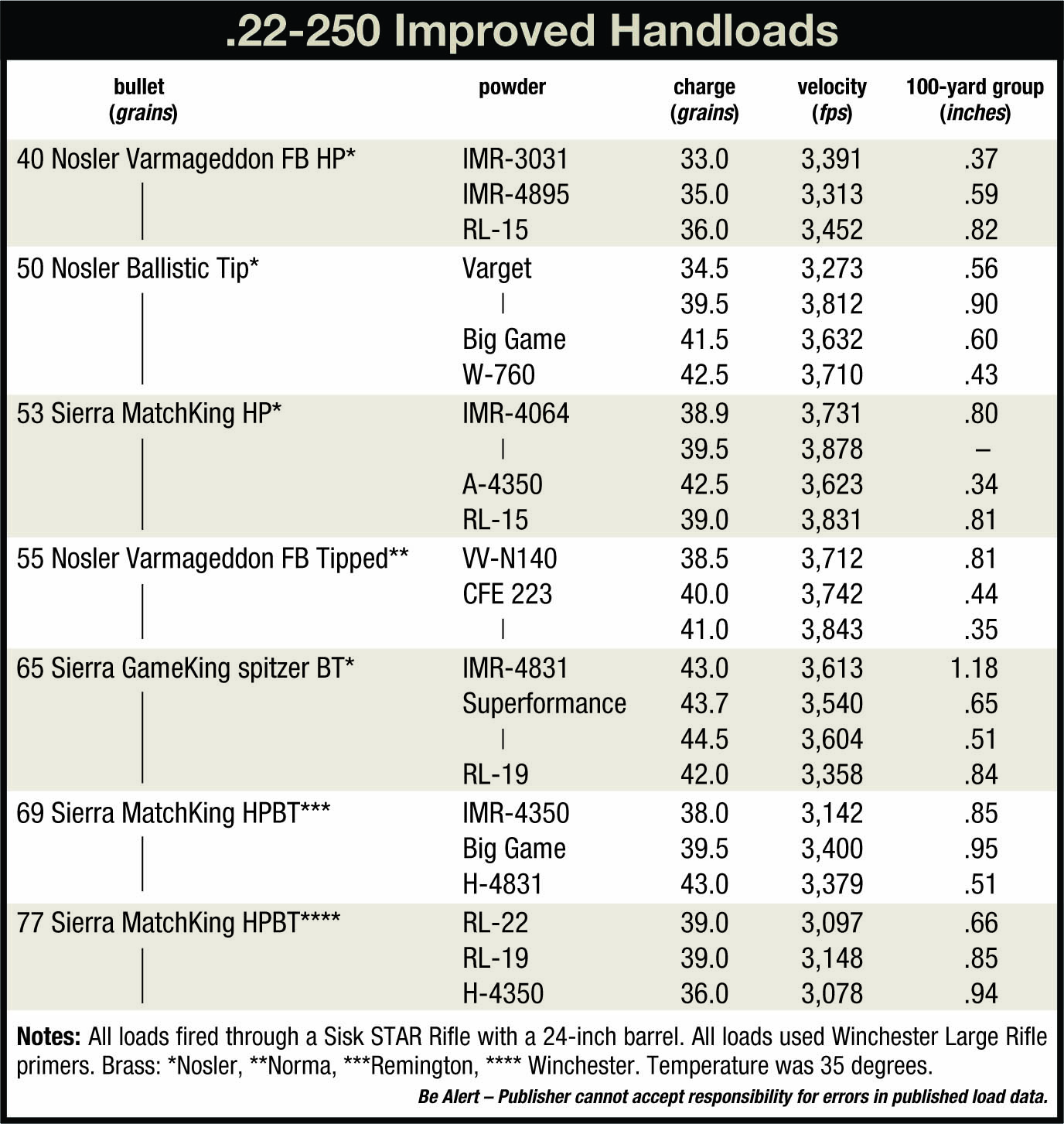

To determine if the improved is indeed a change for the better over the standard cartridge, Charlie Sisk of Sisk Rifles in Dayton, Texas, went all out chambering the improved cartridge in his new Sisk Tactical Adaptive Rifle (STAR). The rifle is based on a Remington Model 700 action with a 24-inch Lilja barrel with a one-in-8-inch rifling twist. The STAR’s aluminum stock has nearly as many adjustments to make it fit a shooter as congress has to increase the national debt.

The .22-250 Improved is often called the .22-250 Ackley Improved, after P.O. Ackley, who designed the cartridge. In volume 1 of his book, Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders, however, Ackley does not hang his name on the cartridge. Instead, he calls it merely the .22-250 Improved and writes that there are two versions of the cartridge, one with a 28-degree shoulder and a second with a 40-degree shoulder.

According to Ackley, the chamber for an improved cartridge has the same headspace dimension as its parent cartridge. For instance, a .22-250 Remington cartridge’s only point of contact in an improved chamber is at the junction of the neck and shoulder. “Creators of improved cartridges did this intentionally in order to produce cases by fire forming factory-loaded ammo of the original chambering in a rifle now chambered for the improved case,” Ackley wrote.

When chambering a .22-250 cartridge in the improved chamber, a slight resistance should be felt as the bolt handle is pushed closed. Federal, Norma, Nosler, Remington and Winchester factory .22-250 Remington cartridges provided this bit of “feel,” as Ackley called it, when the bolt handle was closed. The fired cases from these loads came out perfectly formed.

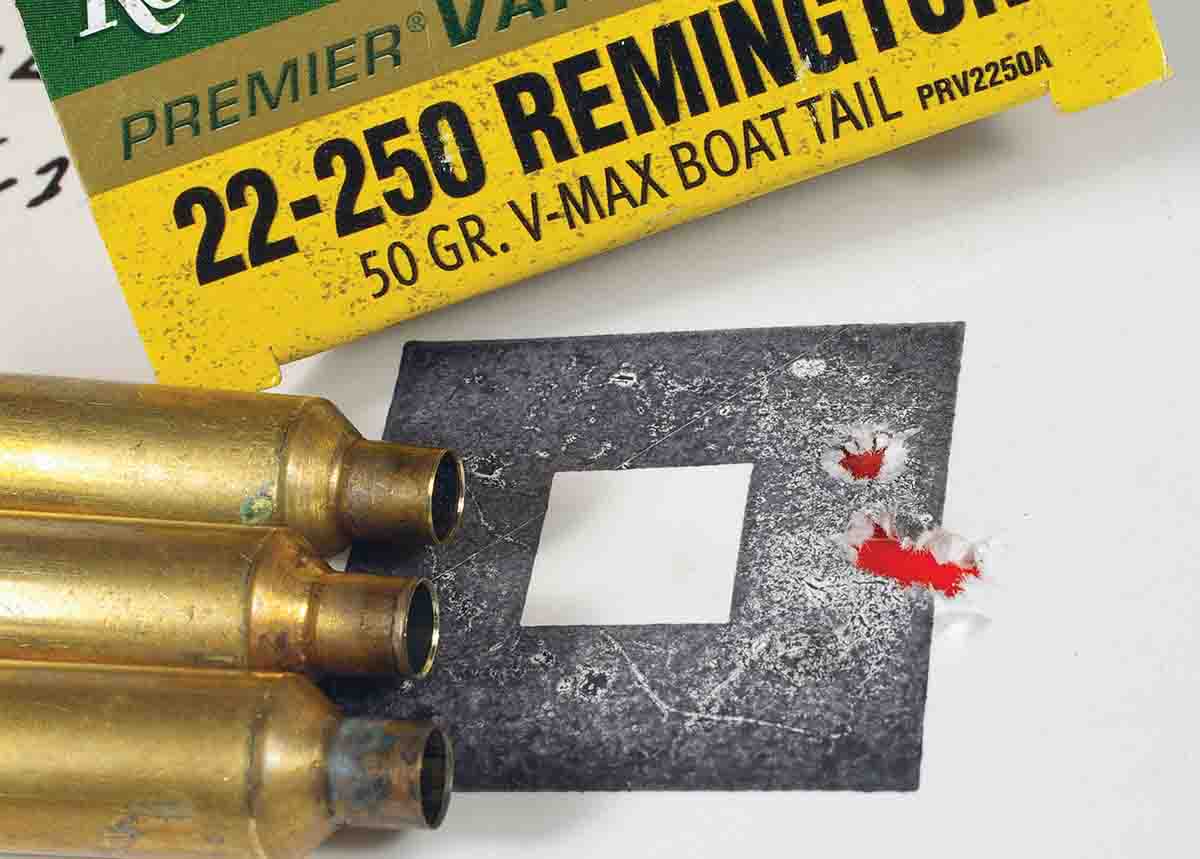

Accuracy was great with those factory cartridges fired in the improved chamber. Remington Premier Varmint cartridges loaded with 50-grain V-MAX bullets and Winchester Supreme loads with 35-grain Ballistic Tip Lead Free bullets shot groups of about .5 inch at 100 yards. Velocities, though, were about 130 fps slower fired in the improved chamber compared to a regular .22-250 Remington chamber. In a pinch, factory .22-250s loads will work just fine.

All the formed cases shortened somewhat during firing. That’s expected as the cases expanded to fill the larger improved chamber. Remington cases shortened from 1.90 to 1.892 inches. Nosler cases shrank from 1.90 to 1.880 inches. That worked well because the trim length of improved cases is 1.892 inches. Winchester Supreme nickel-plated cases measured 1.905 inches before firing. For some reason, those cases remained the same length after firing in the improved chamber. Regular, unplated Winchester brass shortened properly.

On firing, body taper of the improved cases was .014 inch compared to the .22-250 Remington’s .053-inch taper. Shoulder angle increased to 40 degrees, in contrast to the .22-250 Remington’s 28-degree angle. Ackley wrote, “It can easily be demonstrated that comparatively straight cases without much taper combined with the sharp shoulder arrests the forward flow of brass thus preventing the necessity of trimming the cases to length frequently.” I agree, and will add that the stretching that does occur appears mostly when cases are sized.

It’s been written that cases with quite a bit of taper and a gently sloping shoulder also allow brass to surge forward during the pressure of firing, and case necks thicken, but I’ve never had any problem with regular .22-250 Remington cases thickening after firing them a dozen times.

The formed .22-250 Improved cases gained about 10 percent of additional total case capacity compared to the .22-250 Remington cases. Ackley wrote “. . . the design of the improved case is such that after fire forming has occurred the loads can be increased considerably over and above the original to achieve a considerably higher total velocity.”

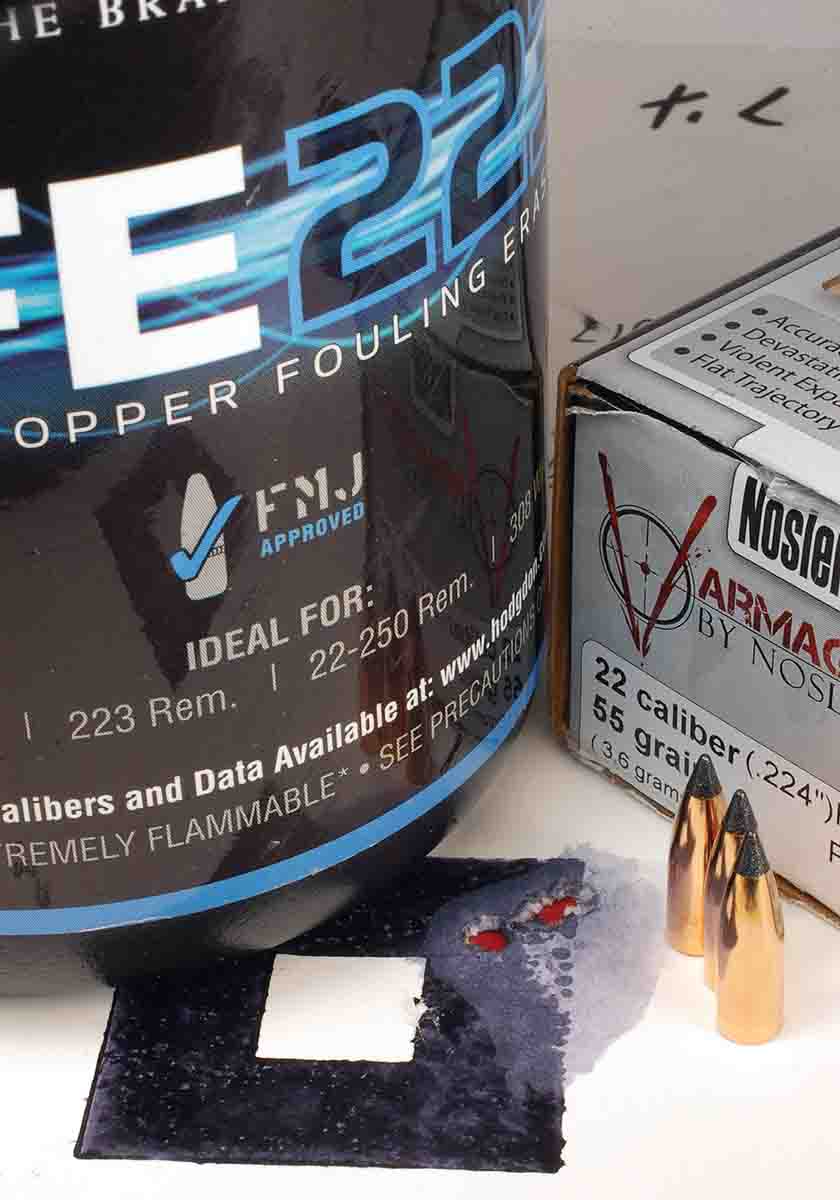

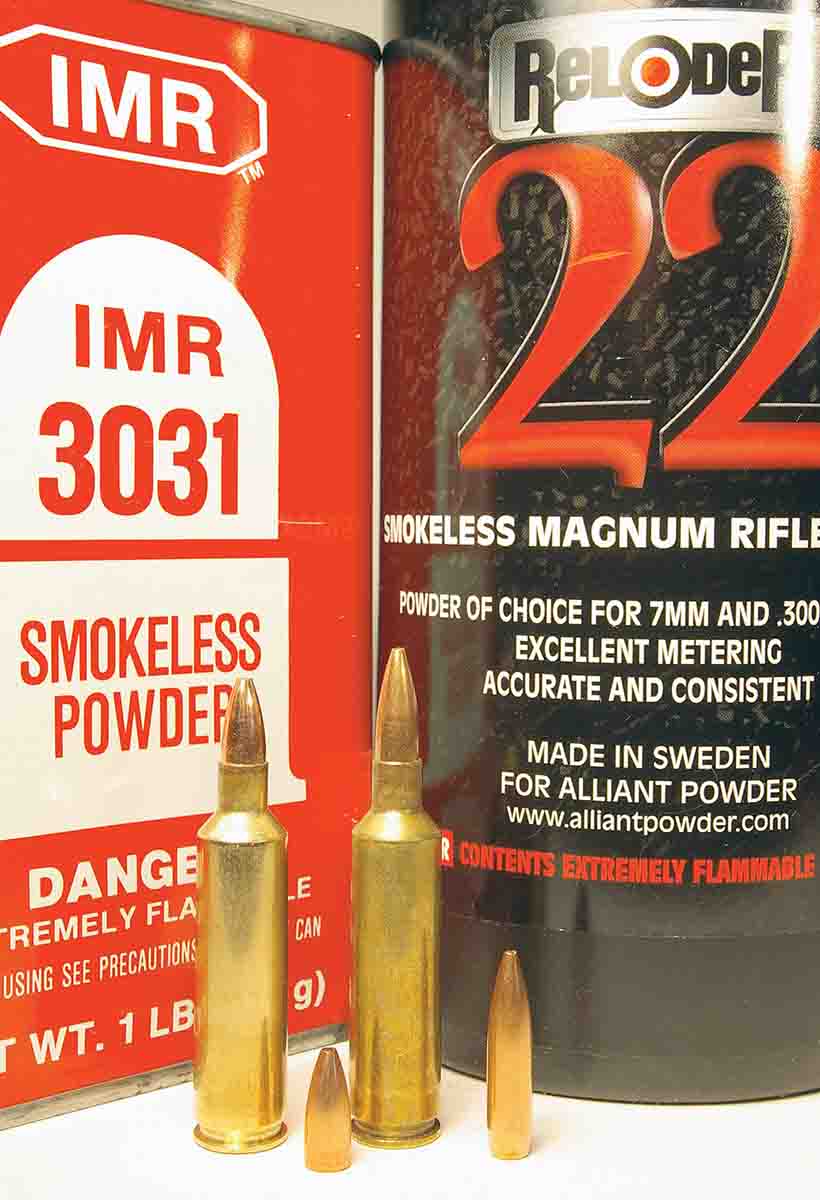

Both cartridges will shoot 40-grain bullets well over 4,000 fps, and sustained shooting of such loads will quickly transform a barrel bore into burnt toast. One of the .22-250’s good traits is its ability to retain accuracy with reduced-velocity loads, and the .22-250 Improved also shares that quality. At the velocity level of the little .221 Remington Fireball, the improved shot Nosler 40-grain Varmageddon bullets into tight groups and with extreme velocity spreads of 24 fps with IMR-3031 and 9 fps for Reloder 15. IMR-4895’s extreme spread was nearly four times as much, but accuracy was still good.

A liability waiver isn’t required to step on the gas of the .22-250 Improved. The additional 2.0 to 4.0 grains of powder fired in the Sisk .22-250 Improved rifle resulted in safe pressures and a gain of about 100 fps over the standard .22-250. However, that velocity level is more than some bullets can withstand from a relatively fast 8-inch twist. Several Sierra 53-grain MatchKing bullets must have disintegrated in flight with a velocity approaching 3,900 fps, because they failed to reach the target at 100 yards. As the load table shows, accuracy was excellent with other bullets.

All in all, the .22-250 Improved has been a good cartridge. Bullet velocity and accuracy are certainly present. I’ve loaded a big batch of cases seven times with stout amounts of powder, and they show no signs of wear. The best part is they have not required trimming.

The Sisk STAR Rifle

After looking through the scope on my rifle, more than one person has commented my head is not screwed on straight. That’s because I hold a rifle tilted somewhat to the left, and to compensate I mount scopes a bit cockeyed so a reticle appears level to my eye, but offset scopes are a thing of the past with the STAR stock. A bolt out the back of the receiver section of the stock threads into a nut in the grip of the buttstock and locks the two pieces together. Splines on the face where the two pieces join allow setting the grip at any angle. Spacers can be added to lengthen the distance from the grip to the trigger and to change grip angle. The captured circular nut is then locked with the fingers or a wrench.

The buttpad is also adjustable. It’s attached to a threaded shaft that extends from the rear of the buttstock that screws in or out to set a length of pull from 12.5 to 14.75 inches. A thicker pad allows extending pull length to 16 inches. The shaft can be threaded into a second, lower hole in the buttstock to drop down the buttpad. Turning the shaft sets the left or right slant of the pad, and two nuts lock the shaft in place. The pad can be further adjusted for height and pitch by screwing it into one of four sets of holes on the recoil plate.

The cheekpiece is a Kydex saddle that extends over the comb. It can be adjusted up or down and with a forward or backward pitch. Two large nuts lock it in place. Shooting from a bench, I set the comb fairly high to position my eye to see through the Leupold scope mounted on a rail high on the receiver. Shooting prone, I moved the comb up a bit more. Index marks on the stock help bring the comb back to previous settings.

The aluminum walls of the receiver portion of the stock are rigid so there is no need for pillars for receiver screws or any type of bedding material to stiffen the stock. The inletting in the receiver portion of the STAR stock cradles a Remington Model 700 action only on the outside of the receiver ring and bottom of the tang. If you want to fiddle with recoil lug bedding, two screws at the front of the receiver can be turned in to push the lug tightly into the recoil lug mortise. A screw on each side of the stock can be turned in to place pressure on the sides of the recoil lug. An optional magazine frame accepts Accuracy International detachable magazines.

Sisk had a devil of a time designing a mount on the front of the receiver portion of the stock to attach the forearm and have it remain tight after taking it on and off time after time. A light switched on when he happened to look at the dovetail mount on a Bridgeport milling machine from the early 1900s. He took the basics of that mount and designed the STAR dovetail that pulls the mount on the forearm back and at an angle into the receiver, tight, every time.

The forearm has a flat bottom and its barrel channel is wide enough that it makes no contact with a barrel 1.25 inches thick. Holes all around the forearm allow attaching bipods, studs for slings and rails for lights and everything else tactical. One forearm model even has a hole in the front for a flashlight set inside the barrel channel.

The whole STAR stock weighs 3.8 pounds. All three parts of the stock are anodized. For now it is made for Remington Model 700 short-action receivers. In the works is a stock for a standard-length Model 700, Savage and Winchester actions. Contact Charlie at siskguns.com.