A Short History of Handgun Cartridges

From Black Powder to Modern Magnums

other By: John Barsness | February, 26

And so the search continues, on into our imaginings. It began with the invention of black powder, probably in the thirteenth century. The first search was for a practical way to make the power of powder portable. While some hand “gonnes” (an early Anglo-Saxon spelling) appeared soon after gunpowder, these were unwieldy, because the metals humans had mastered were relatively weak. The barrel had to be relatively large and heavy, the reason there were far more cannons than handguns in the fourteenth century.

Handguns became truly practical only after we learned to make the iron alloy called steel. Some were pretty powerful, especially cavalry pistols capable of firing roundballs weighing several hundred grains. But early handgun cartridges were weak, and for several reasons.

While “cartridges” had been used almost as long as guns themselves, the earliest were essentially crude versions of the “speed loaders” hunters use today for recharging muzzleloaders. Mostly they were tubes of paper or cloth, containing only a bullet and a powder charge. The spark came from elsewhere, whether a fuse, the stone-and-steel of a flintlock or, starting early in the nineteenth century, a thin metal “cap” containing fulminate of mercury. The switch from flint to cap made self-contained metallic cartridges inevitable. For the first time the bullet, powder and spark could be contained in the same package – and that, of

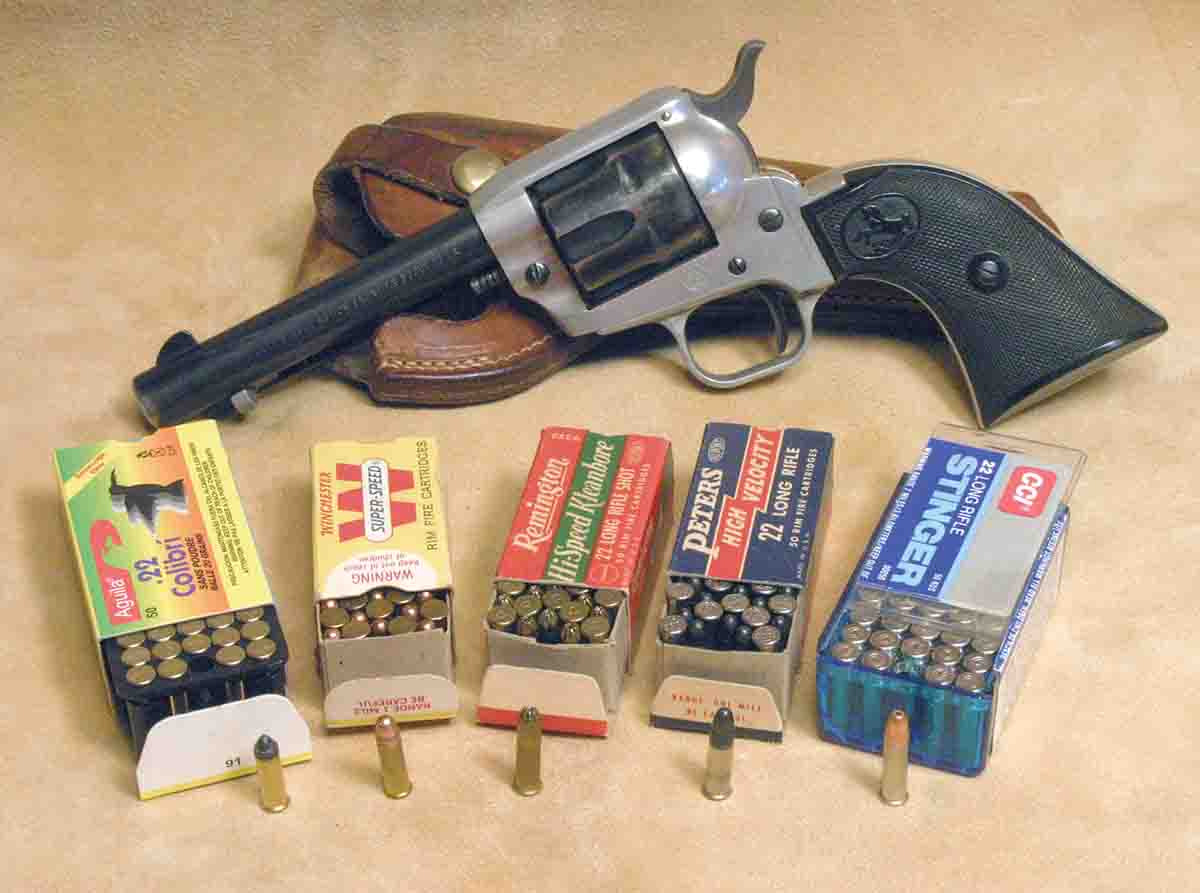

Though a workable centerfire cartridge was invented by a Swiss named Samuel J. Pauly in 1812, the first mass-produced cartridges were mostly rimfire. The rim of the case itself had to be capable of being crushed, meaning the case itself had to be relatively weak. The .22 BB cap is generally considered the first successful commercial cartridge, even though it contained no powder, just a priming compound. Introduced in 1845, it quickly led to a bunch of rimfire cartridges with actual powder inside, ranging in size from the .22 Short to the .56-56 Spencer, both introduced in the 1850s.

In handguns, muzzle velocities of early American rimfire ammunition ran in the neighborhood of 600 fps. Many of these rounds were chambered in early revolvers, in particular the “pocket” models primarily meant for self-defense, but the soft lead bullets from smaller cartridges were often stopped by heavy clothing. In reality, probably more victims of such handguns died of infection than being shot, even after the development of effective antibiotic medicine. (The “germ theory,” as it was called, was controversial into the late 1800s, with many physicians denying that “microbes” could be the cause of infections.)

The next big step was the general introduction of centerfire ammunition. In American handguns this apparently began in the 1860s with the .50 Remington Navy, also known later as the 1871 Army. Muzzle velocities still weren’t much, however, so “power” could only be increased by using heavier bullets. The .50 Remington, for instance, featured a 300-grain bullet – at the same old 600 fps.

By the 1870s, however, several centerfire revolver rounds were pushing bullets of 180 to 250 grains to around 900 fps. Some folks even started “hunting” with handguns, by chasing bison on horseback and filling the unfortunate buffalo full of revolver lead. Among the more powerful and popular rounds were two versions of the .44 Smith & Wesson, the “American” developed for the U.S. military and a slightly longer-cased version for the Russian military. In fact, when the Grand Duke Alexis (son of Russian emperor Alexander II) visited America in 1872, he went hunting with Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and “Buffalo” Bill Cody. Apparently one of the firearms he used was a .44 Russian revolver.

Many practical folks preferred the dual-use rounds commonly known as the .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40. (Today, with the proliferation of cowboy shooting, some purists prefer to call these cartridges by their original names, the .32, .38 and .44 WCFs – “Winchester Center Fires” – as opposed to the .44 Henry rimfire cartridge used in previous Henry and Winchester rifles.) These were introduced in the Winchester 1873 lever-action rifle but were also chambered in popular revolvers such as the 1873 Colt. None qualified as a “buffalo” cartridge, even in rifles, but were pretty popular among cowboys and homesteaders – anybody who didn’t normally hunt anything much bigger than deer and preferred the handiness of using the same ammunition in both sidearm and rifle.

The most popular handgun cartridge, however, was by all accounts the .45 Colt. While the 1873 Colt revolver came in many chamberings, “Colt .45” became an American phrase, eventually even being applied to the original Houston major league baseball team.

The Colt .45 was popular because it was powerful. The primary factory load used a 255-grain bullet and around 40 grains of black powder, for a muzzle velocity of 900 fps or so, depending on barrel length. While this doesn’t seem like much today, it was enough to penetrate the chest of an Indian pony or heavily clothed stage robber – or a deer, elk or buffalo, often desired by cowboys or soldiers tired of beans, moldy bacon and hardtack. At the same time, the handgun itself didn’t cripple the shooter with recoil.

In fact the .45 Colt was so popular that the black-powder load was offered by factories into the twentieth century. My father was raised on a homestead in central Montana, during the 1920s and 1930s when a few grizzlies and wolves still roamed. One of the stories he used to tell was of the last grizzly killed in the Judith Mountains. Apparently two cowboys were out deer hunting, but only one carried a rifle, a .30-06. They surprised a big grizzly at close range, and the guy with the ’06 ran off as the bear charged, leaving his companion to whack away at the grizzly with his Colt. The bear died, full of .45-caliber holes, as it fell on the man.

The single action was relatively rugged and, if loaded correctly (with an empty chamber under the hammer), safe to carry even when its owner was being bounced around on horseback. But it was also relatively slow to fire, unless you were one of the professionals (bad or good) who practiced the art of “fanning” the hammer.

Thus a double-action revolver, capable of firing each time you pulled the trigger, was preferred by a few criminals and lawmen. “Billy the Kid” (born William Henry Antrim but more commonly known as William Bonney) apparently was one of the first to take to double actions, carrying a pair of Colt Lightnings in .41 Long Colt. They didn’t do him much good, since like many gang-bangers of today, he died of acute lead poisoning when only 21. But many upstanding citizens also carried revolvers, especially in rough frontier towns, often preferring a pocket-sized double action.

Thus two distinct types of revolvers started to evolve, one for use on humans and one for everything. Obviously there was some crossover, but in general the double actions were chambered for somewhat lighter rounds and the single actions for heavier cartridges. It’s easier to kill (or frighten away) humans than grizzly bears, and pocket revolvers are much more compact and easy to shoot when chambered for smaller rounds.

Around 1890 smokeless powder arrived. The big change initiated by smokeless was the autoloader. Like Billy the Kid, many professional bad guys, lawmen and military officers were convinced of the virtues of a quick-firing handgun. In general these “automatics” used the same size bullets as revolvers, ranging from .22 to .45 inch diameter. But autos were limited in power both by the mechanics of the action and by the necessity for cases short enough to fit in a stacked magazine inside the grip. The additional zip provided by smokeless powder, however, allowed auto cartridges to match the power of black-powder revolver rounds.

The few years around 1900 saw the introduction of many rounds designed for autoloaders that are still popular today, including the .32 ACP (introduced in 1899), 9mm Luger or Parabellum (1902), .380 ACP (1908) and .45 ACP (1905). In addition, a number of smokeless rounds primarily designed for revolvers also appeared, notably the .38 Special (1902) and .44 Special (1907).

The older black-powder rounds also got a boost from smokeless, though the ammunition companies underloaded them for safe use in revolvers – and cartridge cases designed for black powder. Most of the older rounds used “balloonhead” cases, formed by stamping sheet metal. These were strong enough to hold black- powder pressures, or reduced loads of smokeless, but the new smokeless handgun cases often had solid heads with a much thicker section of brass surrounding the primer.

All these changes had ramifications that affect handguns and their ammunition to this day. The still-existing black-powder rounds will always be loaded by the major factories to lower pressures, even if today’s revolvers and cases can safely operate at much higher pressures. This is so some nitwit with a circa-1880 Colt .45 doesn’t stick high-pressure ammunition in the chamber and blow his hand off.

It’s also part of the reason for another constant in handgun cartridge design: lengthening an existing cartridge case to come up with a “new” round. This started in the nineteenth century. Most rimfire rounds came in various lengths, some existing today in the .22 Short, Long and Long Rifle. When smokeless powder appeared, so did the .44 Special, a longer version of the .44 Russian, chambered in revolvers designed for smokeless powder.

Even handgun rounds designed strictly for smokeless powder are not immune. The .38 Special was lengthened in 1935, becoming the .357 Magnum, and in 1983 it grew even longer, becoming the .357 Remington Maximum. The same thing happened to the .44 Special in 1955, with a longer version named the .44 Magnum. In 2007 an extended version of the .32 Harrington & Richardson Magnum appeared, the .327 Federal Magnum.

Along the way there have been many wonderful attempts at new cartridges, some of dramatically different design. One was the 7.62 Nagant, a .30-caliber round made for a double-action revolver with a cylinder that shifted forward when fired, sealing off the gap between cylinder and barrel common to most revolvers. It worked, boosting muzzle velocities around 50 percent, but apparently was too expensive to manufacture and hard to maintain.

Another great experiment was 1971’s .44 Auto Mag, which reproduced the ballistics of the famous .44 Magnum revolver round in an autoloader. It worked as advertised, but as Cartridges of the World notes: “Unfortunately, the Auto Mag pistol had a rather short, stormy career, marked by more than its share of manufacturing, marketing and mechanical troubles.” Its most basic problem? A Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum revolver was much cheaper and more reliable.

Another sidelight was the .41 Magnum revolver round, introduced in 1964. The .41 still appears in a few revolvers today, but the reasons grow increasingly obscure. Originally introduced as a police round, it supposedly filled the gap between the .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum. But police departments started moving toward autoloaders, and the .40 Smith & Wesson (1989) ended whatever law enforcement potential the .41 Magnum ever had, despite not being nearly as powerful.

This was because better handgun bullets finally arrived, bullets that would both expand and penetrate. The revolution in rifle bullets started soon after World War II, with the development of the Nosler Partition, but for some reason it took longer in handguns. Today we have many fine expanding handgun bullets (including the Nosler Partition).

Prior to the perfection of the expanding handgun bullet, the only ways to increase practical power were to increase velocity (normally by lengthening the cartridge) or make the bullet bigger, both in weight and diameter. This is why many handgunners clung to the .45 ACP as a self-defense round, when today it is steadily being replaced by the 9mm Luger and .40 S&W. The rationale for this trend can still be argued, but it’s a real trend, made possible by better bullets.

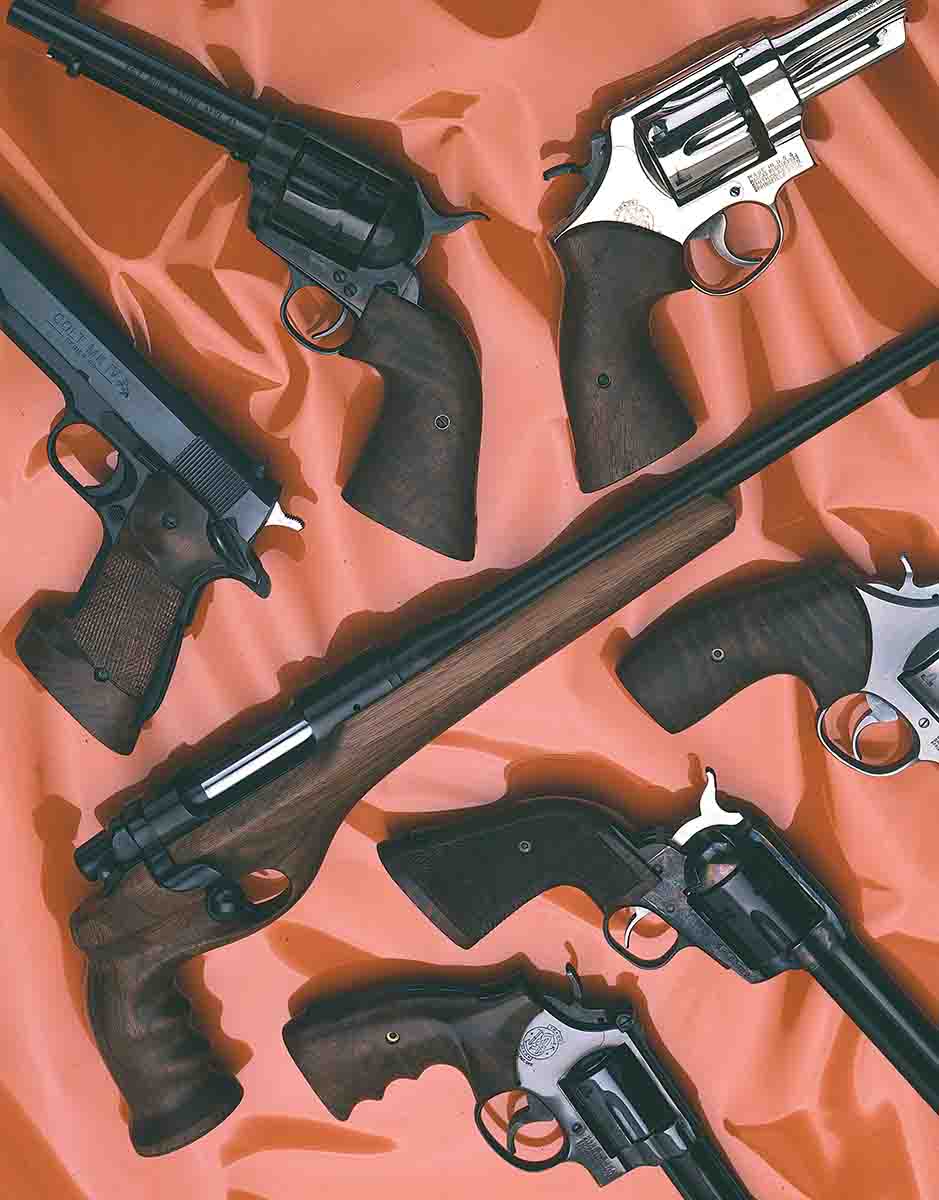

Most substantial handgun cartridge design ended 50 years ago, when the .44 Magnum appeared. Recently I went through the 2008 Gun Digest and totaled up the cartridges chambered in traditional handguns. This total did not include all the different models chambered for the .38 Special, because with all the slight variations in revolvers from, say, Smith & Wesson or Taurus, there would be approximately three bazillion checkmarks by “.38 Special.” Instead, if a certain manufacturer chambered the .38 Special, that counted as one chambering.

Autoloaders (service and sport): 9mm Luger/Parabellum (22), .45 ACP (21), .40 Smith & Wesson (17), .380 ACP (13), .22 Long Rifle (12), .32 ACP (7), .38 Super (6), 10mm Automatic (4), .25 ACP (3).

Double-Action Revolvers (service and sport): .38 Special (9), .357 Magnum (8), .44 Magnum (4), .45 Colt and .22 Long Rifle (3).

Single-Action Revolvers: .45 Colt (12), .44-40 (10), .357 Magnum (9), .38 Special (8), .32-20 and .22 Long Rifle (5), .44 Special and .22 Magnum (4), .32 H&R, .38-40, .44 Russian and .17 HMR (tied with 3).

Now let us ponder these numbers. Of the top two chamberings in all handgun categories, the most recently introduced cartridge is 1935’s .357 Magnum. Both the top two rounds in single actions were introduced in 1873. Aside from the three rimfires, there are 17 chamberings listed. Only four were introduced after World War II, the .32 H&R, .40 S&W, 10mm Automatic and .44 Magnum. The .32 and .44 are essentially power upgrades of older rounds, the .32-20 and .44 Special. Evidently the only real need was for an autoloading round somewhere between the more powerful 9mm/.38 rounds and the .45 ACP, filled by the .40 and 10mm.

Yes, newer rounds have been introduced. Those for autoloaders have mostly fallen by the wayside. There has been a spate of more powerful revolver cartridges, eclipsing the one-time “world’s most powerful handgun” (see Dirty Harry, 1972), the .44 Magnum. But look at the popularity lists. The .454 Casull, .460 Smith & Wesson, .475 Linebaugh, .480 Ruger and .500 Smith & Wesson do not appear.

There’s an excellent reason for this: The average shooter can’t handle the really big revolver rounds. While researching this essay, I visited my local shooting emporium, Capital Sports & Western in Helena, Montana. In recent years there has been some excitement generated by the big revolver rounds in western Montana, both because there are a lot of manly men Out West, and because grizzly bears are becoming more common in the mountains and even on some plains.

But in the glass handgun cabinets of Capital Sports there were no revolvers chambered for any round from .454 Casull to .500 S&W. My friend Tom Brownlee was behind the counter, and I asked him why.

“The guys who want one, have one. But a lot of the guys who thought they wanted one, don’t have one anymore. Look at the used .44 Magnums. . . .” Tom tapped the glass above two .44s, a blued Smith & Wesson and a stainless Taurus. Neither showed much sign of wear. “The average guy can’t even handle a .44, let alone a .454.”

This is the truth. I am an above-average handgun shot and can handle a .44 Magnum or heated-up .45 Colt even in a fairly light revolver. But my one experience with a .454 Casull informed me of my limits. This is not to say the really big revolver rounds are bad cartridges. They are just of very limited usefulness, to a very few people. That’s why the list of most popular traditional handgun rounds is mostly made up of cartridges introduced 50 or 100 or 135 years ago. The truly useful gaps were long ago filled.

The other reason is that the handgun hunters who want more power than the .44 Magnum tend to bypass revolvers and autoloaders and instead buy what a friend of mine calls “hand carbines,” single shots like the Thompson/Center Contender. These are sometimes chambered for traditional handgun rounds; I have Contender barrels for the .32-20 and .41 Magnum, for instance. But far more are chambered for either rifle rounds such as the .223 Remington and .30-30 WCF, or supposed handgun rounds that could just as well be rifle rounds, from the .221 Remington Fireball to the .375 JDJ. (The last not only appears in Contender pistol barrels but Contender carbine barrels.) The 2008 Gun Digest, in fact, lists single-shot factory handguns chambered for rifle cartridges up to the .375 H&H and .450 Marlin.

Obviously this is another evolutionary offshoot of the handgun. These are not sidearms but primary arms, mostly used to either shoot targets or hunt. In general they are not shot offhand, but from rests of one sort or another. This is partly because of their enhanced accuracy. In fact, many of these handguns are more accurate than rifles in the same chambering, primarily because the barrels are shorter, then therefore stiffer. Shooting offhand does not take advantage of their accuracy potential.

The largest examples are also pretty heavy. I have a 14-inch .30-30 WCF Contender barrel with a 2.5-7x T/C scope mounted. On a G2 Contender frame it weighs 4.5 pounds and is capable of one-inch groups at 100 yards – as long as it’s shot with some kind of rest, whether over sandbags or with a bipod. With the bipod it comes very close to weighing exactly the same as a Model 94 Winchester carbine.

Many other such single-shot pistols are built on bolt actions, and some weigh even more than many of today’s super-light “mountain” rifles. Obviously there is some crossover here between handguns and rifles, but it is worthless to quibble over it. Lots of people like to shoot big handguns, and I like to shoot about any kind of sporting arm, one reason I own a few hand carbines.

With a good rest and enough time to aim, they are capable of astonishing performance. One day with my friend Rod Herrett (Herrett’s Stocks, Inc.; www.herrett-stocks.com), I shot dozens of prairie dogs out to almost 400 yards with several of Rod’s bolt-action handguns chambered in rounds up to .22-250 Remington, and Rod killed one at over 600 yards. That would be pretty good shooting with a rifle.

How far will the evolution of such handguns go? Some people would be happy to make a pronouncement on that, but I can’t, because despite most traditional handgun cartridge development ending shortly after smokeless powder appeared, we keep seeing new stuff. Now we have at least one revolver cartridge, the .460 S&W, capable of giving the .30-30 WCF a run for its money – in handguns. Who knows what will happen next?