Handloading the .222 Remington

The Classic “Triple Deuce” (2011)

other By: Brian Pearce | February, 26

.jpg)

Not so very long ago, the .222 Remington was king of the medium-velocity .22 centerfire cartridges, serving countless var-mint shooters and dominating in Bench Rest competitions. From several aspects, it is a historically significant cartridge and still deserves consideration from the discriminating rifleman.

To help understand the .222, it was developed to fill the void between the .22 Hornet (and .218 Bee) and the .220 Swift, driving 50-grain bullets around 3,200 fps. Its case was a completely modern rimless design with a 23-degree shoulder, ideally suited to handloading. If the rifle is accurate, one really has to be “off the playing field” to assemble handloads that won’t shoot. Case life is long, and barrel life is normally around 7,000 or 8,000 rounds (at least for minute-of-varmint accuracy) due largely to the modest pressures and rather small powder charges. Looking the case over, one can’t help but notice the .222 resembles a scaled-down .30-06. The .222 is the parent of the .222 Remington Magnum, the .223 Remington, .17 Remington, .204 Ruger and several wildcats. (Certainly the case was not stretched to create the above cartridges, but rather was the basis for them.)

.jpg)

From a varmint shooter’s standpoint, the .222 Remington is a jewel. The small charges of powder offer economical high-volume shooting and long barrel life, reducing the overall expense involved. Recoil is truly mild, even when chambered in “walking” varmint-style rifles, and muzzle blast is never an issue. While the Deuce can’t offer the long-range performance of the .220 Swift or .22-250 Remington, it is an honest 250- to 300-yard varmint number, which covers the majority of varmint shooting needs.

Mac’s rifle was built by “the family,” so to speak. He had built the action (from his brother’s design) and fitted it with a Pat McMillan barrel. Gail McMillan moulded the fiberglass stock, with Mac fitting it to the barreled action. The 50-grain bullets came from J-4 Precision Jackets and were driven with 23.5 grains of Hodgdon BL-C Lot No. 1 powder (no longer available). Ignition came from a CCI BR-4 (bench rest) prototype primer (which are currently available).

.jpg)

In my early years of guns and shooting, the .222 Remington was commonplace among fellow ranchers, who used guns for controlling coyotes or varmints, and every boy at school who was a shooter/hunter was familiar with the Triple Deuce. It was even occasionally pressed into service for taking larger game, such as deer and pronghorn. Before I was even old enough to hunt big game, I watched as one of my older brothers dropped a pronghorn buck with a single shot through the lungs with a Savage chambered in .222. (This is certainly controversial, and we will discuss it further in a moment.) When dealing with coyotes, bobcats, prairie dogs and other small critters, the cartridge is excellent.

Handloading the .222 Remington

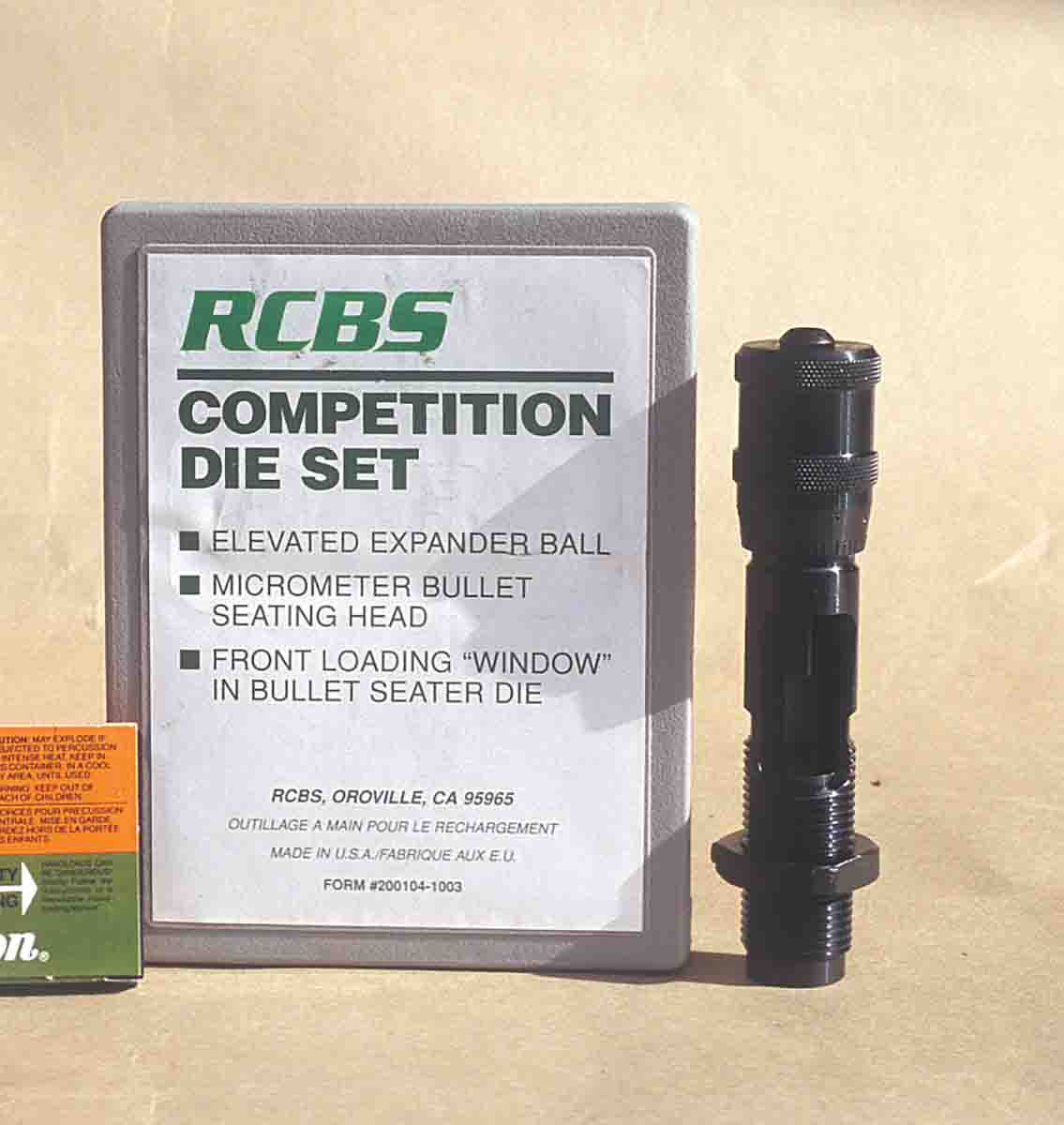

It is relatively easy to assemble accurate handloads for the .222 Remington. If developing loads for the

There are many excellent powders for handloading the Deuce, including several that were popular during its heyday, as well as some worthy newcomers. Examples include Hodgdon H-322, H-335, H-4198, BL-C(2), H-4895, Varget, Alliant Reloder 7, Winchester 748, IMR-4198, IMR-4895, IMR-3031, Vihtavuori N133, Western Powders X-Terminator and Accurate AA-2015, AA-2460 and AA-2520.

It was easy to duplicate factory ammunition ballistics driving a 50-grain bullet 3,140 fps with several of the above powders, including H-322, H-335, Varget, VV-N133, AA-2015, RL-7, IMR-4198 and X-Terminator. With select powders it was possible to exceed those speeds by 100 and even up to 240 fps. With that said, some of the most accurate groups were obtained with loads that were achieving 2,950 to 3,200 fps. Personally, I would select loads based on accuracy rather than loads that were giving the extra velocity.

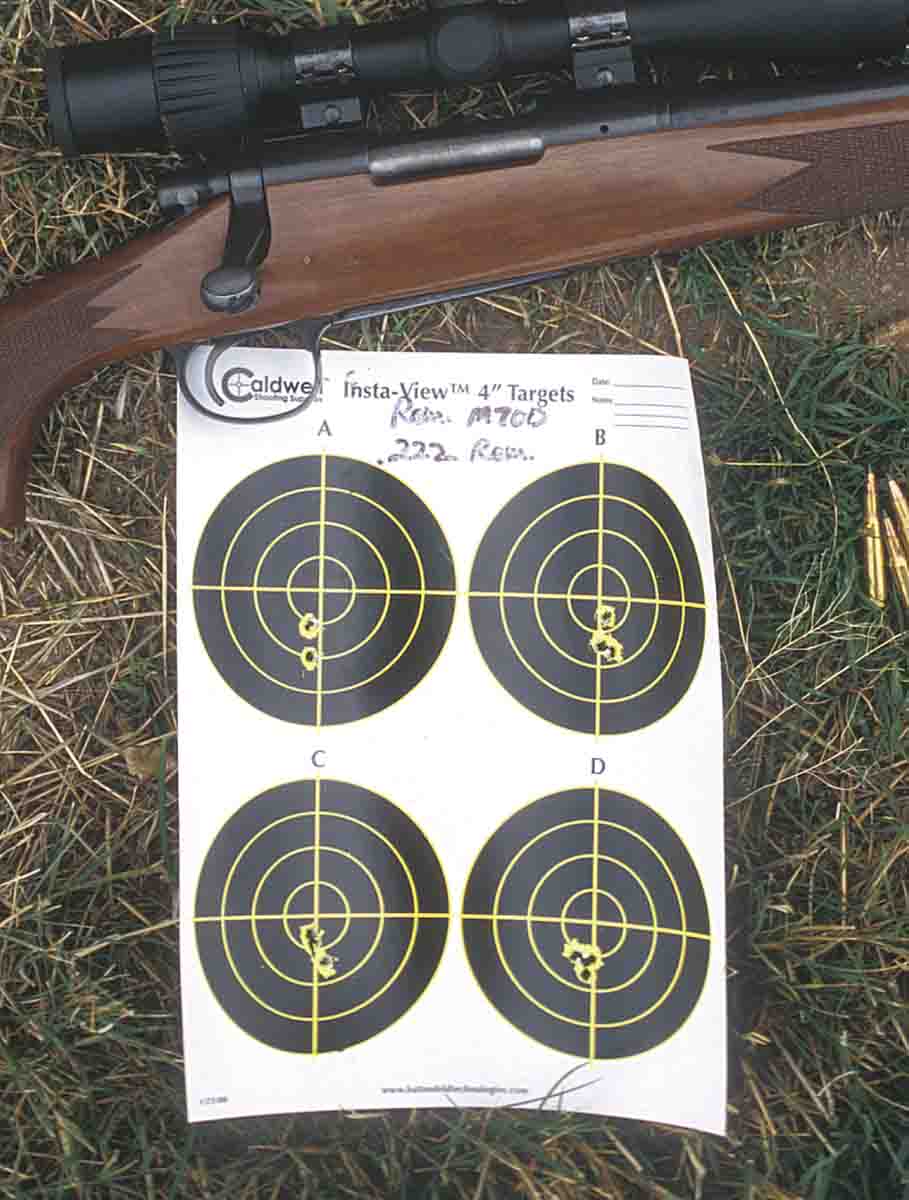

In developing the accompanying data, a Remington Model 700 Classic with a 24-inch barrel was used. This rifle was a “Limited” version produced during 1993. With decades of practice, Remington has the accuracy end of things figured out, as this rifle groups under .5 inch with several loads. Years ago, when I first purchased this rifle, I basically threw together a load that consisted of 19.0 grains of IMR-4198 with a 55-grain Sierra hollowpoint capped with a Remington 71⁄2 primer (for about 3,050 fps). The first four shots cut a three-leaf clover.

With this being a standard weight barrel (.645 inch at the muzzle) rather than a heavy varmint outfit, I chose to install a light variable scope for “hike and hunt” use, taking coyotes and other suitable game. A Weaver Grand Slam 3-10x with a 40mm objective in black matte finish was installed in Weaver rings. This is a top-notch scope featuring an aircraft grade one-piece aluminum tube and multicoated lenses to reduce glare and increase light transmission. It is waterproof, shockproof and offers Micro-Trac 1⁄8-MOA click adjustments with a “real world” retail price of around $300. When adjusting this scope, there was no guessing, as the click adjustments positively moved bullet impact exactly where it was supposed to be.

Most rifles chambered for the .222 Remington feature a one-in-14-inch twist, as did the Remington Model 700 Classic used. This twist is best when used with bullets weighing 40 to 55 grains. Some guns will stabilize bullets weighing up to 60 grains (as did this Model 700), but best accuracy was obtained with 50- to 55-grain weights.

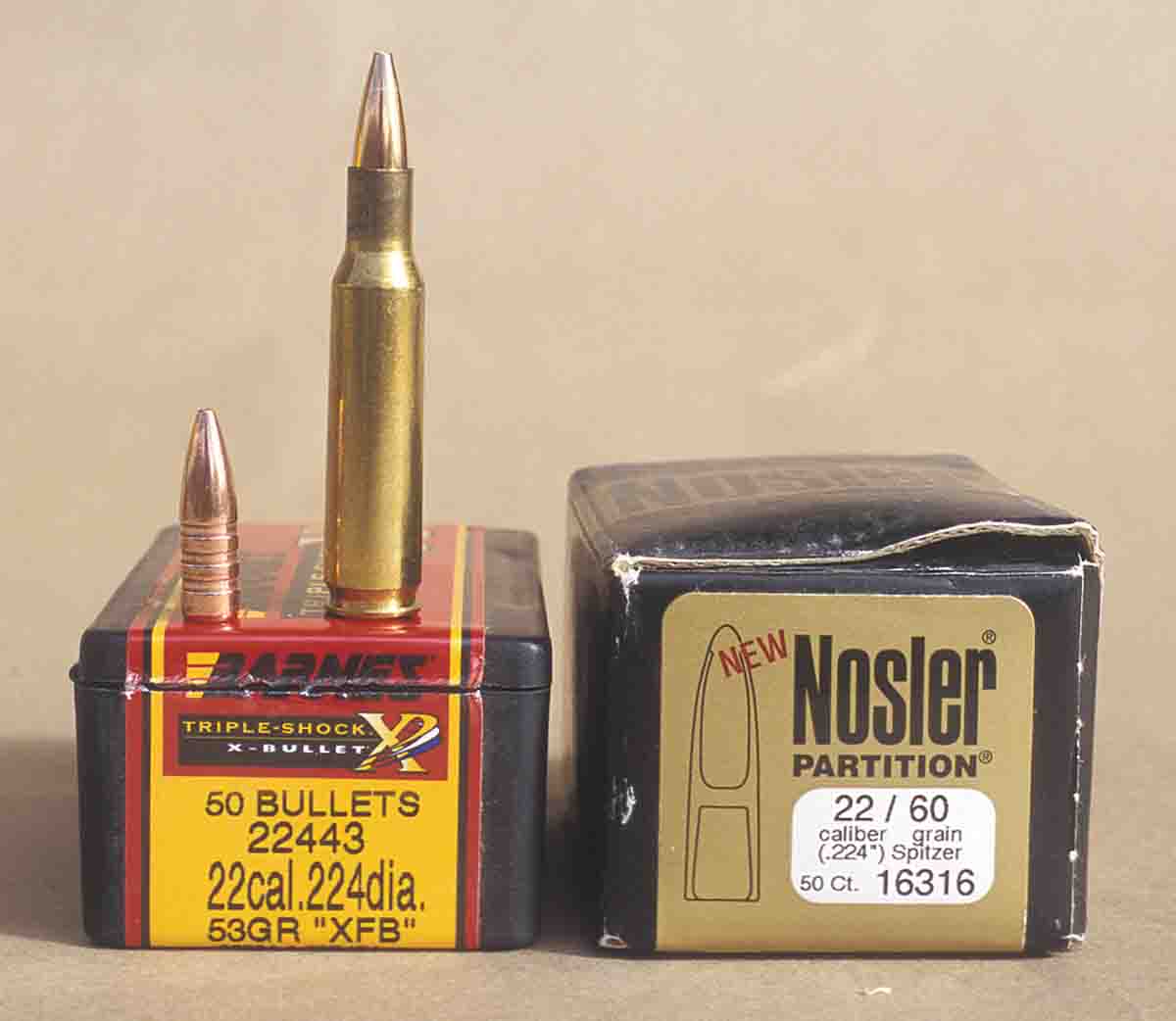

Most .222s will be put to work in varmint towns, but it’s also worthy for thumping coyotes, and the list of truly excellent bullets for these purposes seems nearly endless. A few examples include Speer’s 50-grain TNT hollowpoint and 52-grain hollowpoint, Nosler’s hollowpoint boat-tail, Hornady’s V-MAX and SX and Sierra’s 50-grain BlitzKing. The 50- and 52-grain weights are excellent general-purpose choices in the Deuce, with the 55-grain versions having an edge on windy days or long distances. For those who want to attempt deer with a .22 centerfire (where legal), data was included using the 60-grain Nosler Partition, as well as the Barnes 50-grain X-Bullet and 53-grain Triple-Shock X-Bul-let. I know this is a controversial application, but if the range is limited and bullets placed correctly, deer can be taken cleanly. Any of the above three bullets will drive completely through on broad-side shots.

Today industry operating pressure for the .222 Remington is established at 46,000 CUP. Certainly most bolt-action rifles will allow the cartridge to be loaded to greater pressures, similar to the .223 Remington or .222 Remington Magnum, which run 52,000 and 50,000 CUP, respectively. To me this seems to take away some of the little round’s virtues, such as low muzzle blast and long barrel life, and as previously stated, some of the most accurate loads were not top-velocity numbers. For example, using the 50-grain Speer TNT hollowpoint driven by 20.0 grains of IMR-4198, muzzle velocity was 3,257 fps, while 20.5 grains went 3,326 fps and 21.0 grains produced 3,381 fps. Of the three, the 20.0-grain load gave the lowest extreme spreads and best accuracy, while the 21.0-grain load came in last in both categories. These results are by no means conclusive, as they were only fired in one rifle, but the low extreme spreads cannot be ignored. And there were other loads where similar observations were made.

Often at the conclusion of a handloading article, I’ll select two or three loads that gave the top results in a given gun, then assemble a quantity of ammunition for future use in the field. In this instance, there were literally dozens of combinations that produced truly remarkable accuracy and performance. This is mentioned as a testament to just how easy the cartridge is to handload and obtain excellent results. Furthermore it shows the stiff competition, or should we say high-quality products, of bullet and powder manufacturers. In this respect we most definitely live in a “Golden Era.” For the above reasons, in the accompanying data, there are no comments specifying the accuracy of loads, as doing such would be “splitting hairs,” so to speak, and would best be determined from a real match rifle or the individual rifle they will be fired in.

Easy to load, pleasant, economical, long barrel life and world record holder best describe the Deuce. If you are a discriminating rifleman or woman, this cartridge is a worthy addition. Sorry, but you’ll have to find your own, as mine isn’t for sale!

.jpg)

.jpg)