Loading the 7.7 Arisaka

Among the Strongest Military Actions

feature By: John Barsness | February, 20

One of the obscure mysteries of smokeless centerfire rifles is the existence of a few cartridges slightly over .30 caliber, which might be called the “kinda thirties.” This tiny trend began with the .303 British in 1888, which according to many references uses barrels with a .303-inch bore diameter and .311-inch grooves. However, in the three .303s I have owned – a Lee-Enfield Mk. 4 No. 1, a Ross Model 1910 and a special-run Ruger No. 1A made in 2010 – slugging the barrels resulted in bore diameters from .301 to .304 inch, and grooves from .310 to .313. This is more variation than a larger number of slugged “real thirty” bores.

The second “kinda thirty” cartridge was the 7.65x53mm Mauser, which appeared the year after the .303 in the 1889 Mauser rifle. The cartridge and rifle were adopted by the army of Argentina, the reason the round became popularly known as the 7.65 Argentine, but it is also used by several other countries. While 7.65 millimeters equals approximately .301 inch, at least one reference claims it equals .303. Most references suggest groove diameter is .313, but the authors may be similarly math-challenged. Having never owned a 7.65x53, I cannot provide any hard evidence, but might have to fill that information gap in the near future.

The .303 and 7.65x53 may have filled the immediate desire for “kinda thirty” cartridges, because a half-century passed before the next (and apparently last) appeared. In 1939 the Japanese Imperial Army adopted the 7.7x58 round, a more powerful cartridge than the 6.5x50 round used since 1905 in two early Arisaka bolt rifles.

Most references list the 7.7’s bullet diameter as .311 inch, and most handloading manuals suggest using the .311, to .312-inch bullets offered by several manufacturers. However, as most handloaders know, rifle bores can vary, one reason I could not pass up an unmodified (except for one small detail) Type 99 Arisaka leaning in the used rack at Capital Sports & Western Wear in Helena, Montana. It even included the original canvas, side-mounted sling.

The Japanese writing on top of the receiver ring translates to “99 Type,” but the serial number stamped on the side of the action is in Arabic numerals. The one small modification is right in front of the receiver ring inscription, a slightly rough area where a stamping representing a 16-petal chrysanthemum flower was removed. This symbol indicated ownership by the Emperor of Japan, and when the Imperial Army’s rifles were surrendered at the end of the war, the stamping was ground off.

Various sources list the weight of Type 99s as around 8.5 to 9 pounds, but that probably includes the bayonet, an exceptionally long-bladed model that in original form was essentially a short sword. Early-production World War II bayonets featuring a hooked quillion (the crossguard of the handle) to tie up an opponent’s bayonet – or sword, since even well into the twentieth-century swords were still issued to many soldiers, including all Japanese officers. My bayonet-less rifle weighs 7.6 pounds.

Several boxes of .311- and .312-bullets were on hand, but of course handloading would require brass and dies. When Type 99 rifles started showing up in the U.S. after the war, the only 7.7 brass available was Japanese military with Berdan primers, which are a pain in the rear to decap.

Back then quite a few rounds still used Berdan primers, so both primers and decappers were pretty common, but the 7.7x58 also happened to be yet another minor variation on the basic 8x57 Mauser “rimless” case, copied by cartridge designers around the world since 1888, including the U.S. military when it created the .30-06. The 7.7’s base and rim are very close to the .30-06’s diameter; the cartridge drawing in the Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, Tenth Edition, shows a head diameter of .471 inch and a rim diameter of .470. As a result, many post-war U.S. handloaders reformed and trimmed Boxer-primed .30-06 brass.

Today, however, both Norma and Prvi Partizan make new Boxer-primed 7.7x58 cases. An Internet search revealed Prvi Partizan brass on the Graf & Sons website, along with a Lee Precision set of “7.7 Japanese” loading dies for a very affordable price.

While waiting for the order to arrive, considerable research revealed some historical disagreement about the rifle and cartridge – though also indicating my Type 99 was a lucky purchase in several ways. While the rifle was obviously in pretty good condition (including a semi-shiny bore), it also turned out to be early production.

More than one reference lists standard barrel length as 25.9 inches, but this one measures 25.6, closer to the 25.5 of the Type 99 used as a test rifle in Hornady’s manual. My rifle’s rifling twist is 1:10.5 while the Hornady manual lists 1:9.5. However, such twist variations are pretty common in older cut-rifled barrels; I have found more than an inch difference in twist rate even in high-quality sporting rifles such as the Savage 99.

I retouched the muzzle crown with a Brownells hand-tool, then slugged the 4-groove barrel with 00 lead shot. Measured with a Starrett digital caliper, the bore turned out to be a consistent .301 inch in diameter. The grooves measured .315 to .316 inch and were more than twice as wide as the lands.

The Type 99 Arisaka action has been described as a pre-98 Mauser type, since it cocks on closing and has the same sort of extractor and bolt stop. Interestingly, the floorplate is one of the few hinged models found on military bolt actions, with the release inside the front of the trigger guard.

The safety is essentially the wide cocking piece, almost 1.1 inches in diameter in my rifle, which also blocks escaping powder gas. To put the rifle on “safe,” push the knob forward then turn it clockwise a few degrees, whereupon it locks the bolt down. Like some other old bolt-action cocking pieces such as the 1903 Springfield’s, the flare of the cocking piece allows recocking the bolt manually in case of a misfire, though the safety is slow and clumsy compared to the Springfield’s lever.

On the other hand, the Arisaka is one of the strongest military bolt actions ever made. Perhaps the best-known tests were performed by P.O. Ackley, where both Type 38 6.5x50s and Type 99 7.7x58s proved tougher than several other military bolt actions, including the 98 Mauser and 1917 Enfield, but Frank de Haas also cites another such test in Bolt Action Rifles (1971).

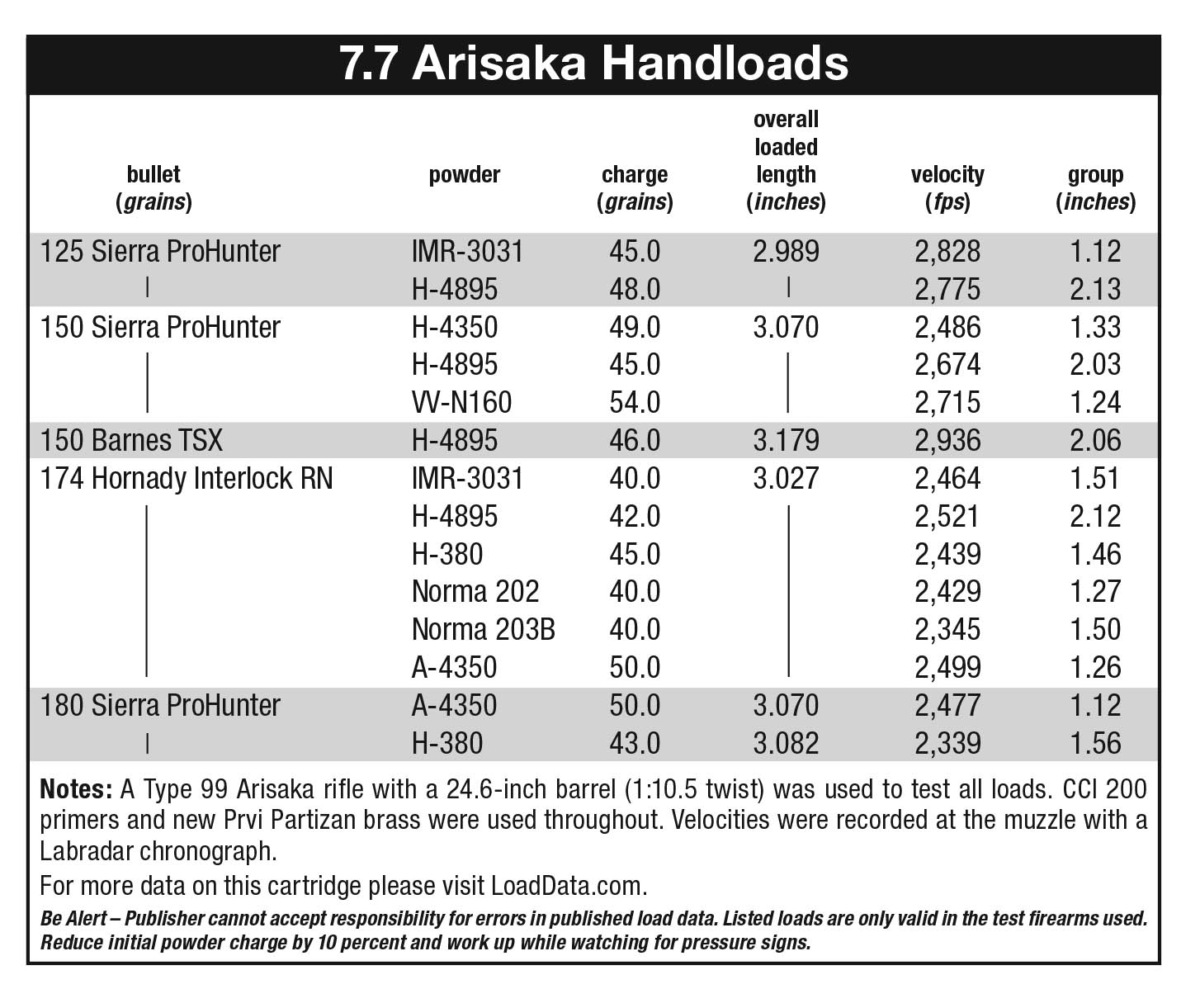

Following my usual procedure, recent data was searched for powders listed as producing the highest velocities for each bullet weight. Hornady’s 174-grain .312-inch Interlock was selected to start the tests, partly because a bunch were on hand and partly because, according to several references, the original Japanese service load used a bullet of 175 grains at 2,477 fps. (However, apparently even those numbers are in dispute – or perhaps varied during the war. The Hornady manual claims a 184-grain bullet at 2,390.) However, by 1939 just about every army in the world, including Japan’s, had switched to spitzer bullets, so the 174-grain Hornady roundnose is not historically correct anyway.

The first range test took place at 25 yards, mostly to see where the rifle shot with its folding, two-aperture rear sight. The standard aperture, with the sight lying flat, is non-adjustable and regulated for closer ranges, while for long-range shooting a second aperture slides up and down a flip-up, 2.5-inch ladder. The trigger is two-stage, typical of military (and even some sporting) bolt actions of the era, with a secondary pull of around 5 pounds, but due to being pretty crisp it was easy to use.

At 25 yards the standard aperture resulted in a pretty high point of impact. I expected this, since older military rifles were often regulated to shoot high at closer ranges to result in hits with a centerhold on vertical targets out to normal distances.

However, point of impact was also consistently to the right, as much as 2 inches. When I initially tried to move the front sight sideways in its dovetail with a Williams sight-pusher tool, it would not budge, understandable in an 80-year-old rifle, but an overnight soaking with Kroil penetrating oil loosened it up.

The high elevation, however, took a little more work. The front sight is a tapered post attached by a dovetail that was far too small for any of the front sights in my collection. Eventually I added a “silver” bead to the top, using a small triangular file to cut a slot in a piece of No. 3 steel shot, then epoxying the shot to the top of the sight with Brownells ACRAGLAS GEL.

My rifle is missing the anti-aircraft “wings” on the first Type 99 ladder sights. The rifle appeared a couple years into the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the antiquated Chinese military planes could not fly high or fast, and generally lacked armor. The 99 sight included a pair of flip-down steel bars on either side of the ladder, marked with the estimated speed of the planes. In use, Japanese soldiers set the aperture for the approximate range and used the speed-marks on the bars to lead fighters and bombers. Obviously, this was not precision shooting, but the anti-aircraft bars were normally used in multi-rifle barrages. As Japan’s conflicts expanded to include countries with faster, higher-flying and better-armored planes, the anti-aircraft wings were abandoned.

The heads of the new Prvi Partizan cases measured .471 inch, exactly the same as the Hornady manual’s drawing, and not much more after firing: You have to look pretty close to see the tiniest hint of a bulge. This is contrary to many old handloading reports, which mention noticeable bulging of fired cases, perhaps because of sloppy chambering in late production rifles.

Quite a few Arisakas were converted to other cartridges. An older elk outfitter I knew in the 1990s had a 99’s barrel set back and rechambered to .308 Winchester, and the bolt handle changed and action drilled and tapped for scope use, as a back-up rifle for his clients. He said it grouped most factory ammunition into 2 inches or so, which back in the innocent twentieth-century was considered well under “minute-of-elk.” (My rifle feeds and extracts .308 Winchester ammunition pretty well, which is understandable since the basic body diameter of the .308 and 7.7 is similar.)

I do not know how many other Type 99s have .301-inch bores, but decided to try .308-caliber bullets to see how well they might work, since .308s obviously shot okay in my outfitter friend’s rifle. On hand were Sierra 150-grain ProHunters and Hornady 180-grain Spire Point Interlocks, which were loaded with the same powder charges that grouped best with .311-and .312-inch bullets.

Unfortunately, neither shot anywhere near acceptably, probably due to the deep, wide rifling allowing powder gas blow-by. Muzzle velocities were not only 75 to 100 fps slower than with .311/.312-inch bullets, but the velocity of individual rounds varied widely, resulting in vertical stringing of up to 4 inches at 50 yards.

I also suspect the rifling might have been why the Barnes 150-grain TSX, a bullet that has shot well in .303 British rifles, did not match the accuracy of the lead-cored bullets: The solid copper TSX does not tend to “bump up” in diameter like lead core bullets, even when booted with faster-burning powders.

The water capacity of the fired Prvi Partizan cases with 180-grain bullets seated was right around 50 grains, very similar to the .303 British and .308 Winchester. As a result, when loaded to the same pressures, all three are capable of similar muzzle velocities, though I would not recommend pushing the 7.7 much unless the rifle is thoroughly checked out, due to possible large differences in chamber and bore dimensions. However, if you are one of the many handloaders who likes to fool around with older rifles, a Type 99 can be a lot of fun.