New Powders in the .220 Swift

Speed and Accuracy

other By: John Haviland | April, 26

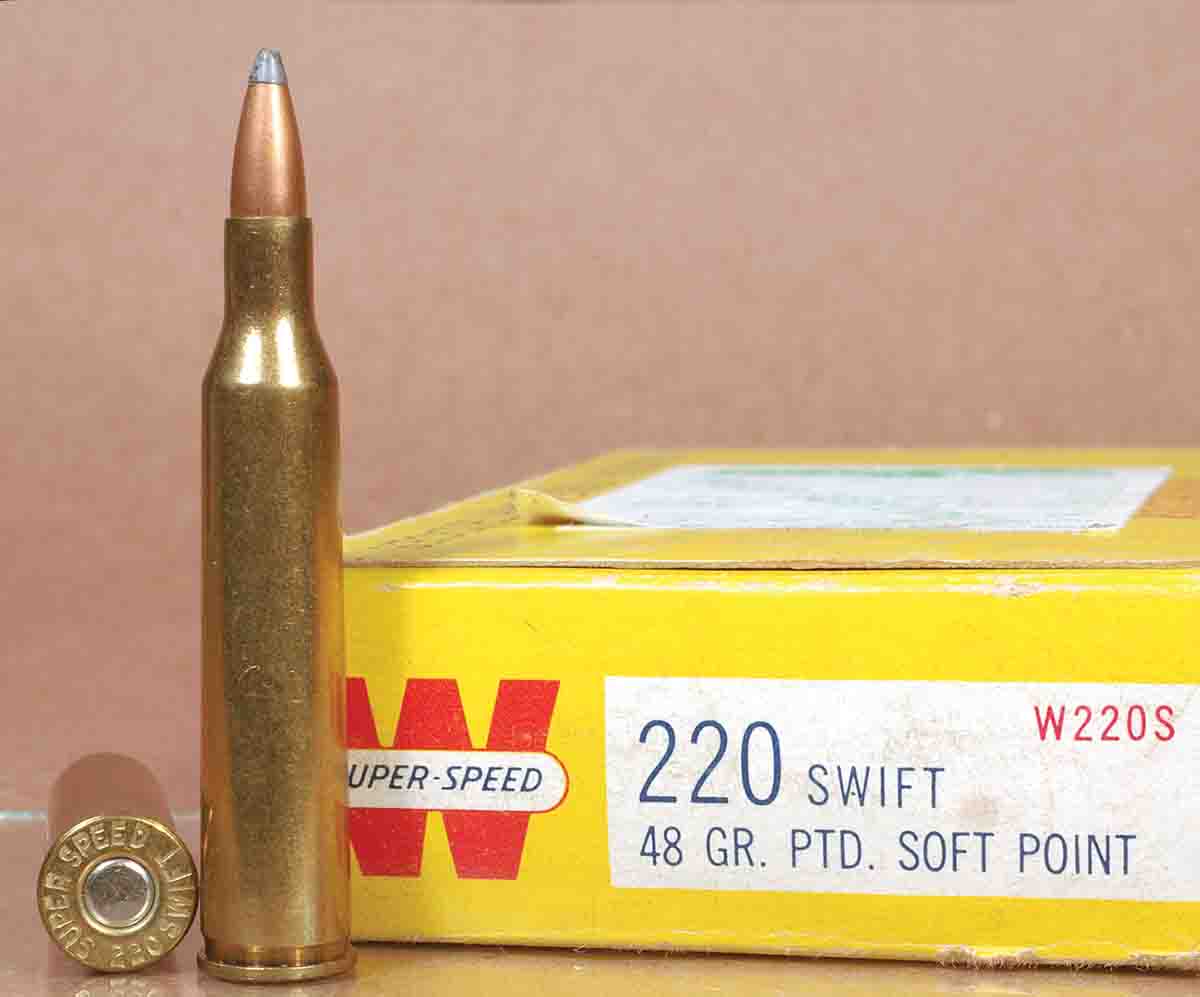

You don’t hear much about the .220 Swift these days. The .22-250 has stolen its long-range thunder, commercially, anyway; and everyone is shooting the .223. A bunch of new powders, however, make the Swift just as good or better than it ever was as King of the Varmint Cartridges.

Recent powders from Accurate, Alliant, Hodgdon, IMR, Norma, Ramshot and Vihtavuori provide a new array of options for loading the Swift. I’ve been shooting these powders in a Winchester Model 70 Varmint Swift made in 1961. While I’m still a big fan of the .22-250, these powders made the Swift sing an accurate and speedy song – so much so, that I’m wondering why I didn’t buy a Swift a long time ago.

A few of these powders produced low extreme spreads of velocity in my Swift. Norma’s 203-B turned in velocity spreads of 41 fps with 40-grain bullets and 29 fps with 50-grain bullets. Vihtavuori N150 went as low as 9 fps with 40-grain bullets and 18 fps with 53-grain bullets. With 55-grain bullets, Reloder 17 and Big Game produced spreads between 36 and 41 fps. Often, heavier bullets in a cartridge produce the lowest velocity spreads. That may be because heavier bullets require slower-burning powders that fill more of the case, and the heavier bullets are longer and protrude down into the case farther. One or the other, or both, of these situations keep the powder in a uniform position so it burns more consistently.

That was certainly the case with the relatively heavy Sierra 63-grain Semi-Point bullet. The Swift’s barrel remained fouled after nearly 100 rounds when the Sierra bullets were fired. Extreme velocity spread was 74 fps for Accurate 2700, 20 fps with Hybrid 100V, 8 fps for Reloder 19 and 12 fps for H-1000. The average group size of the Sierra bullets was .81 inch for the four groups.

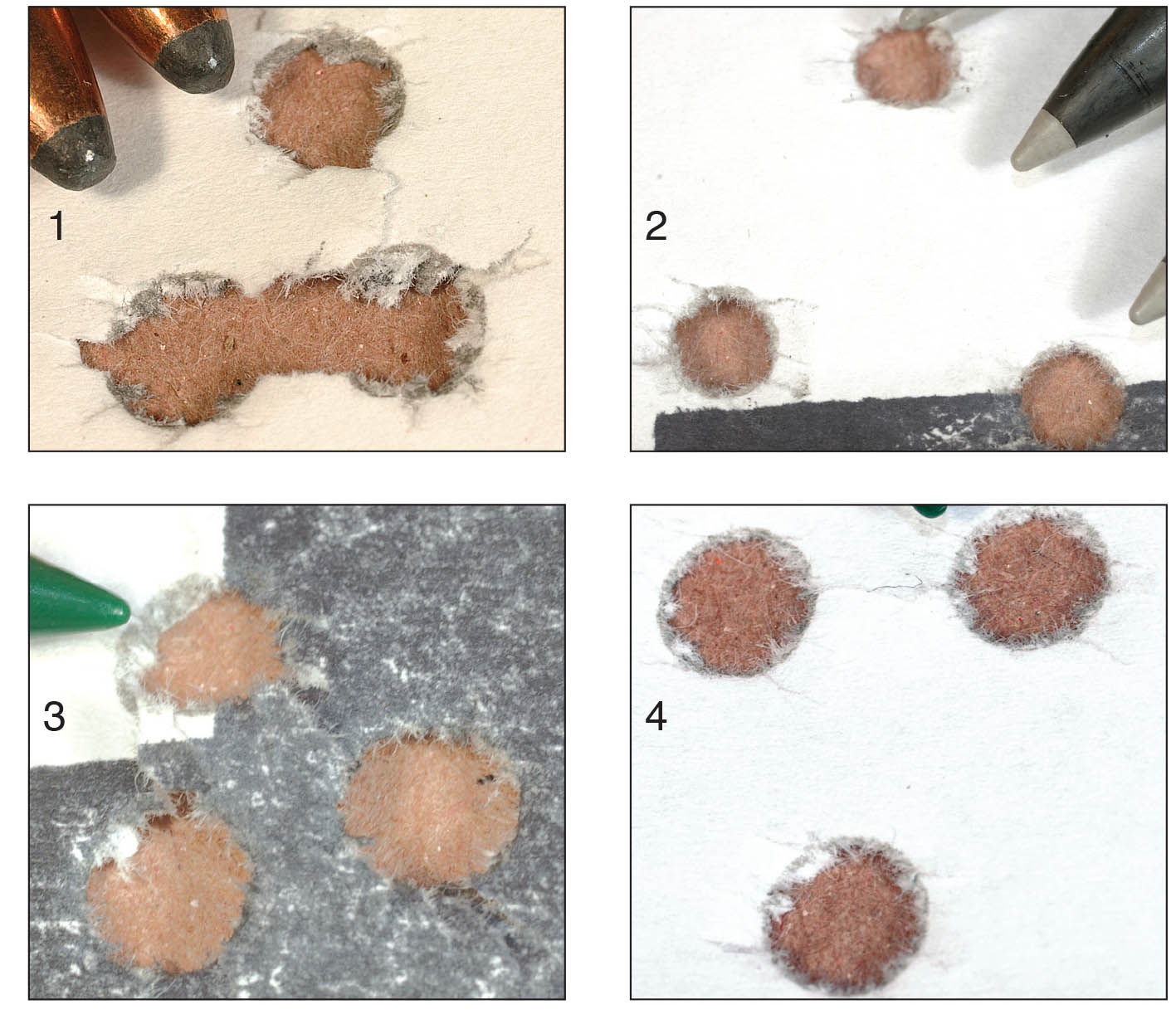

The Swift has always been known as an accurate cartridge. My Model 70 Varmint shot a few loads in .5 inch and tighter at 100 yards. The Sierra 50-grain BlitzKing grouped as tightly as .33 inch with Accurate 2700. The Sierra 53-grain Bench Rest hollowpoint shot consistently well with four different powders, with groups between .77 and .94 inch.

I sighted in the Swift with Remington 55-grain Power Lokt hollowpoints and 44.0 grains of Hunter last spring in preparation for a day of sending ground squirrels to that clover patch in the sky. The last three bullets I fired landed in .178 inch at 100 yards. This proves good bullets group well when fired through a good barrel.

Certainly the shape of the Swift’s case has nothing to do with its precision. In fact, the Swift case is the antithesis of what is considered a correctly shaped case for the best accuracy. Its rim sticks out like a sore thumb and that can’t be beneficial for a precise fit in the chamber. Its long tapering case body and sloping shoulder also fall short of providing an exact cartridge fit. But, still the Swift shoots well.

Swift cases did stretch quite a bit in the Model 70 when fired with maximum loads. The Winchester cases that had been fired a couple of times were sized enough to set the shoulder back .002 inch. The cases were trimmed to 2.195 inches and then fired. Three of the fired cases had lengths of 2.204, 2.205 and 2.206 inches. That’s quite a bit of stretch. In fact, those measurements are right at the maximum case length for the Swift.

I measured the cases in the various stages of sizing to determine if the cases grew in length more during sizing and at what stage of sizing. One at a time, I ran each case into an RCBS sizing die, and then partially pulled out the case enough to loosen it from the die. I unscrewed the expander ball stem, and with the expanded ball still in the case, removed the case from the die and measured the case lengths. Then I threaded the stem back into the die and pulled the expander ball out of the case mouths. The lengths of all three cases in various stages of loaded, fired and completely resized varied as shown in Table I.

The Swift cases did stretch quite a bit on firing, and then some more when the cases were run into the sizing die. Even though the inside of the necks were lubricated, pulling the expander ball back out of the cases took a bit of elbow grease on the press handle. But this force did not lengthen the cases. In fact, expanding the necks decreased case length ever so slightly. So we can lay to rest the old myth that pulling a case neck over an expander ball increases case length.

There have also been reports for years on end about the Swift’s high pressure causing brass to flow forward and increase the thickness of case necks. I inserted a bullet into all the fired cases used to shoot the loads listed in the load table. The bullet easily slipped into the case necks, indicating no brass had extruded forward on firing to thicken the necks. I also measured the thickness of the necks of a few cases that have been fired several times, and the measurements remained the same.

However, two of the Swift cases out of 100 had splits on the necks after being reloaded five times. That has never happened to me with the thousands of .22-250 Remington cases I’ve reloaded over the years. The .22-250 cases usually last about 12 firings, and then a few out of a batch will crack in front of the head.

Cartridge Comparisons

New and old handloading articles suggest problems with the Swift will disappear if powder charges are backed off a couple of grains, but that turns the Swift into a .22-250 Remington. Top speed .22-250 loads, fired from 24-inch barrels, come up about 100 fps short of the Swift. The Cartridge Comparison table lists some top velocities with various bullet weights from the Swift and several other high-speed, .22-caliber cartridges. As the table shows, the .223 Winchester Super Short Magnum, in turn, beats the Swift by 100+ fps, and the .22-250, with its 4-inch shorter barrel, beats the .225 Winchester by about 100 fps. This comparison proves the more powder burned and the higher the pressures, the faster a bullet leaves the muzzle.

If these four cartridges are fired at a prairie dog town 500 times a day over a long weekend, their barrels would function only as tomato stakes. The solution is to keep the rate of fire at a slow and reasonable rate so the barrel on a Swift and these other cartridges will last years on end. That’s why my old Model 70 Varmint Swift will make only brief appearances on the prairie and the hay field.

The Swift was introduced in 1935 in the Winchester Model 54 bolt action. It was said the heavy amount of powder the Swift burned and the high velocity of its bullets quickly ironed out the Model 54’s mild steel rifling lands as flat as a road-kill jackrabbit on a paved highway in the heat of an August afternoon. The Swift was also said to produce squirrely pressures with maximum loads. Those criticisms and condemnations have pestered the Swift ever since, even in rifles built with much more wear-resistant barrel steel.

Would the Swift be received on better terms today as a new cartridge than back in the 1930s? No, it would parallel the short and unhappy life of the .223 Winchester Super Short Magnum. Even before Swift rifles were on sporting goods shelves, the Internet would be ablaze with tales of torched barrels after firing as few as 300 rounds and a cartridge whose accuracy fell off to dismal after firing as few as 20 rounds. Of course, the Swift’s rimmed case would bring up slurs of cartridge feeding problems. Before hunters even had a chance to shoot a Swift, the cartridge would wear a black eye as a crippler of deer.

On a prairie dog shoot-’em-up a few years ago, I shot a Swift in a Remington Model 700 electronic ignition EtronX, and my partner banged away with a .22-250 in the same model rifle. We both shot Remington EtronX loads with Hornady 50-grain V-MAX boat-tails. The stated velocity of the V-MAX bullet was 3,725 fps from the .22-250 and 3,780 fps from the Swift.

Before we started shooting, we decided to compare notes on any differences we saw between the Swift and .22-250 cartridges. However, over two days of shooting, we never observed any distinction between the two. Recoil was identical, the barrels heated up at equal rates, and the barrel bores seemed to foul the same when we cleaned them. We shot at prairie dogs from 100 to somewhat over 400 yards. We hit prairie dogs quite regularly. We also missed high and low, and, when the wind blew, off to the side. We decided by the end of the shoot there was little sense buying a new Swift because the immense popularity of the .22-250 Remington meant many more rifle and ammunition choices.

.jpg)

Winchester dropped the Swift in 1963 when it revamped its Model 70. The replacement .225 Winchester, which was sort of an abbreviated Swift, was an immediate dud. About 20 years ago, the Swift made somewhat of a comeback. Ruger and Savage chambered rifles for the Swift but dropped the cartridge a few years ago. Cooper Firearms will still make you a Swift in its Model 22 single shot, but Remington is the only major manufacturer still chambering the Swift, and that’s in a single rifle, the Model 700 Varmint SF.

Still, there are lots of Swifts out there. I finally got mine in the Winchester Varmint and with these new powders, I plan on shooting the King of the Varmint Cartridges for a long time.

.jpg)

.jpg)