Powder or Cartridge - Which Came First?

Evolution and Necessity

other By: R.H. VanDenburg, Jr. | February, 26

The question, as put to me by Editor Dave Scovill, was simple enough: Which came first, the powder or the cartridge? It is a good question, but any one-word answer would be vastly simplistic. So, while trying not to overly complicate things, let’s take a stroll back in time.

Not too far, though, as the word cartridge is somewhat limiting, and the word powder is construed to mean smokeless powder. Still, we can’t ignore its predecessor, black powder. Black powder evolved over centuries. Noisemaker, explosive, cannon propellant and finally a propellant for small arms were, and are, among its many uses. When used in arms, both powder and ball or shot were loaded from the muzzle.

One of the concepts learned over time, especially in the propellant arena, was that of burning rate. Different applications required different burning speeds that could be controlled by the size and shape of the powder granules. In black-powder manufacture, the separating of granules by size is accomplished by sifting the powder through a series of screens. Smaller granules burn more quickly than do larger ones. Through trial and error, manufacturers learned to tailor their powder to the requirements of the application. The change to smokeless powder did nothing to lessen the importance of the concept.

Skipping over a lot of innovation and refinements, we come to the era of the cartridge case and loading self-contained ammunition from the breech. The powder was still black. Early on we didn’t even have suitable guns. We had to develop them and the cartridge; only the powder was already available, although some tinkering with burning rates may have been required. In quite a few instances, it proved necessary to modify existing muzzleloading arms.

When our military, in 1866, decided to arm its soldiers with breech-loading rifles and carbines, it developed the .50-70 Government cartridge: a 450-grain lead bullet over 70 grains of large-grained black powder at a reported 1,260 fps. The guns, the Springfield Model 1866, were actually Model 1861 muzzleloading arms modified by cutting away the breech end of the barrel and installing a “trapdoor” style breechblock. The .58-caliber barrels were lined to accommodate the new .50-caliber bullets. Newer models, with proper barrels, were soon to follow. Over the next three decades, there was a plethora of new guns and cartridges developed for rifles, shotguns and handguns. All the cartridges were self-contained, all utilized already existing black powder of appropriate grain sizes.

Smokeless powder was not too far away. In 1883, French chemist Paul Vieille was the first to successfully produce a gelatinized nitrocellulose that became smokeless powder. By 1885 the powder, called Powder B, was in production, and by 1886 the French had a new rifle, the 1886 Lebel, and the first smokeless powder cartridge, the 8mm Lebel. As a point of departure, the French already had the single-shot Gras rifle and a metallic, albeit black-powder, cartridge, the 11mm Gras. The new rifle was a bolt-action repeater; the new cartridge was but a modification of the old, clearly showing its Gras heritage.

Other nations were quick to follow suit with Germany moving from its own Model 71, 11mm Mauser with its black-powder cartridge to the 1888 Mauser, predecessor to the famed ’98 Mauser. Both latter cartridges were also 8mm. The British were to announce their .303 British cartridge, first in 1888 with black powder as the propellant. In 1892, the propellant was changed to cordite, a smokeless, double-base powder cut into “cords” or spaghetti-like strings rather than kernels or flakes.

Clearly, in the case of the 8mm Lebel, even though there was a case with which to begin work, the rifle, cartridge and powder designers had to work hand in hand to finalize cartridge dimensions, including bullet caliber and weight. The Germans essentially started from scratch as the 11mm Mauser was a rimmed cartridge; the cartridge they ended up with, the smokeless 8mm Mauser, rimless. Again, all parties had to work together. The British adopted their rifle and cartridge before the adoption of smokeless powder, therefore the onus fell on the powder manufacturer to adhere to existing specifications.

In 1892 the U.S. government, eager to replace its single-shot Springfield rifles (by then chambered for the black-powder, .45-70 Government) turned to the Norwegian Krag-Jørgensen bolt- action repeating rifle. Its caliber was 8mm, but the U.S. had decided on .30 caliber as ideal for its needs. The new cartridge was still rimmed, and its case appears to have been derived from the new British .303 but slightly larger with less taper and a slightly larger rim. It was originally called the .30 U.S. Army, but we know it today as the .30-40 Krag.

Smokeless powder production in the U.S. had begun in 1890. Early government loadings of the .30 U.S. Army consisted of a 220-grain full-metal-jacketed bullet propelled by the famous Peyton powder manufactured by the California Powder Works. In 1894 the army put out a request for a new powder. According to Phil Sharpe, in his magnificent Complete Guide to Handloading, “Specifications were more or less general and gave merely the dimensions of the cartridge case and bullet; a velocity of 1960 fps at 53 feet was desired, with a mean variation of but 20 f.s. in 40 rounds and a maximum pressure of 38,000 pounds.”

Obviously quoting from the original specifications, Sharpe went on to say: “The powder must be free of dust, smokeless, must not corrode barrel or cartridge case or require an unduly strong primer or leave a hard adherent residue in the barrel. It must not be sensitive to shock or friction or be so friable as to break up in transportation. It must permit of machine loading with variations not over 3⁄10 grain in 50 consecutive loadings. It must not give excessive heat in rapid fire. Preference will be given to American powder and those of nitrocellulose types.”

Here the powder manufacturers had the gun and the cartridge, as well as some broad specifications as a guide. In 1896 Laflin & Rand Powder Company’s W.A. .30-caliber powder became the official service powder and remained so until 1908. This means that not only were most .30 U.S. Army (.30-40 Krag) cartridges loaded with it, but also the .30-03 and .30-06 cartridges were developed around this powder! Only after 1908 were powders again developed for the existing military cartridge.

This was an era of immense change elsewhere as well. Shooters were being introduced to new smokeless powder cartridges, such as the .30 WCF and the .25-35 Winchester, and shooters, powder and ammunition manufacturers alike were anxious to have the old black-powder cartridges loaded with smokeless powder. A number of powders were developed as bulk-for-bulk, that is volume-for-volume replacements for black. It is said that Laflin & Rand’s famous Sharpshooter smokeless powder was developed expressly for the .45-70 cartridge. It saw wide use there in bullet weights from 300 to 500 grains.

In the lighter weights, velocities could be held to black-powder standards or increased significantly while not exceeding old “trapdoor” Springfield safety considerations and even higher in the 1886 Winchester for which the cartridge was also chambered. At the 500-grain bullet weight, Sharpshooter was still an excellent smokeless duplicate for the full 70 grains of black, developing 1,300 fps or so while using 23.2 grains. Again quoting from Sharpe: “The Sharpshooter load developed less pressure than the black, 18,000 psi to 25,000 psi according to Hercules.” Sharpshooter also found favor in a host of other cartridges from the tiny .22/15/60 Stevens to the .50-110 Winchester. It was a double-base powder and matched up well with the lead bullets of the day. It was close to today’s 2400 in burning rate.

We now come to the beginning of the modern era that Scovill most likely had in mind to begin with. New cartridges were popping up like mushrooms after a rain, and new powders were being developed at almost the same rate. Cartridge development was mostly along sporting lines. Powder development was promoted along two fronts: internally, as the natural desire to improve the product line as technology improved, and externally as military needs grew. Technological improvements included reducing barrel fouling and wear, ease of ignition, reducing the powder’s tendency to absorb or lose moisture, improving shelf life, among others; also the ability to control burning speeds chemically as well as through granule geometry.

The W.A. powder that was used in the early military of the .30-06 gave way to a single-base powder, successively known as DuPont 1909 Military, DuPont Military #20 and Government Pyro .30 Caliber DG. It served as our service .30-06 powder through World War I and was standardized as a canister powder under the name DuPont MR 20. The MR series of DuPont powders was replaced by an early IMR series, which included such powders as MR 13, 15, 16, 17 and others. Technological improvements continued, and by 1935 DuPont had introduced an improved IMR series that contained powders familiar to us today: IMR-4227, 4198, 3031, 4064 and 4320. IMR-4895, 4350, 4831 and 7828 were still to come. As was often the case, many of these powders were developed to meet some military need but were found to exhibit great versatility across the cartridge spectrum. Of course, as new and better powders were developed, the civilian market expanded its cartridge offerings.

In the early 1930s, Hercules developed a new powder ideally suited for small rifle cartridges, such as the .22 Hornet. The powder was released to the public in canister form in 1933 as 2400. It didn’t take long for big-bore handgun experimenters to try it in their sixguns. When Doug Wesson announced his intentions to lengthen the .38 Special case to create a more powerful handgun cartridge, chemists and ballisticians from Winchester, Remington, DuPont and Hercules, along with technicians from Smith & Wesson, worked together to create, in 1935, the .357 Smith & Wesson Magnum. The powder they chose for factory ammunition was 2400. In time both factories and reloaders used it in .410 shotshells.

Cartridges of modest case capacity had the best of it during this period, as even the slowest of rifle powders were fast burning by today’s standards. Still, large case capacity cartridge development continued. An example of a cartridge that was better than the powders it had to work with was the .30 Newton.

Apparently an outgrowth of the earlier .30 Adolph Express (circa 1912), also developed by gun and cartridge designer Charles Newton, the .30 Newton was introduced about four years later in Newton rifles. It had a larger case in length and diameter than the .30-06 and gave quite impressive velocity figures at 50,000 to 55,000 psi with powders in the burning rate range of our modern IMR-3031 to 4895. Had the cartridge been developed in the 1940s or 1950s when powders such as 4350 and 4831 became available and been chambered in more arms, it might still be with us.

Throughout smokeless powder production, some powders had been standardized sufficiently to be offered to the reloading public as canister powders. In addition, in the U.S., the government had frequently sold surplus powders to National Rifle Association members. After World War II, Bruce Hodgdon forever changed the reloading scene dynamic by purchasing large quantities of surplus military powder and offering it to the shooting public. It began with surplus 4895, which had been the World War II-era .30-06 powder, but followed with a powder DuPont had developed for use in the army’s 20mm cannon called 4831. It didn’t take long for shooters to realize that here was a powder slow enough to allow for an increase in case capacity in many bore sizes, but also that it was ideal in the .270 Winchester, .25-06 and others. With its own powders being sold by the government as surplus and ending up in the hands of potential DuPont customers, DuPont took awhile but eventually expanded its own canister line to include such powders as 4895 and 4831.

The years following World War II saw another change: the expanding competition of powder companies. For the most part, early smokeless powder reloaders used DuPont powders. After the DuPont breakup in 1912, we used single-base DuPont rifle powders and double-base Hercules handgun and shotgun powders. Hodgdon changed all that. In the 1960s, Winchester began to offer some of its Ball powder line to handloaders. Foreign companies such as Norma began exporting its canister powders to the U.S. Other companies such as Accurate Arms set up to import other foreign powders, many surplus military powders from Europe. As surpluses dried up, newly manufactured powders from all over Europe made their way here.

There were now several forces at work at the same time. New and improved powders to meet military and industrial needs, including the law enforcement and sporting markets, were still required. There was the need to be competitive – more so than in the past – as any potential contract would have multiple bidders. Also the canister market put pressure on the manufacturers both to be competitive and to meet the needs of new cartridges.

In the early part of the twentieth century, when federal regulations began to place restrictions on waterfowl hunting, including gauge restrictions, the industry responded by increasing the shot weight. Before long we were shooting 10- and 12-gauge shotguns that carried as much shot as earlier 6- and 8-gauge guns. All this demanded new and improved powders.

Another outside influence that had an effect on sporting ammunition also occurred in the shotgun field. The mandate for the use of nontoxic shot in waterfowl hunting initially was limited to steel shot. To be effective, steel shot required a higher velocity than lead. To accomplish this required a slower powder than was currently available. It took some time – and the development of new, stronger wads – but now steel shot loads have reached a level of perfection and acceptance not dreamed possible two decades ago. Those slower powders and stronger wads have subsequently led to the development of newer, nontoxic substances that are even more effective than lead.

An example of new military needs occurred as postwar militaries upgraded their shoulder arms to autoloading and automatic, or selective fire models. There developed a real need for powders that produced a constant port pressure regardless of atmospheric conditions.The Australian Defense Industries (ADI) was one company that responded. Its success filtered down into its sporting ammunition and canister powders, some of which are sold in the U.S. under the Hodgdon Extreme series label.

Also into the mix we must throw this: Ammunition manufacturers rarely manufacture their own powder. Much like the military, but frequently on a smaller scale, they solicit bids from competing powder companies to meet their needs, whether for a specific cartridge or a series of cartridges. One such powder that evolved out of this arrangement is known throughout the industry as Bullseye 84, a Hercules, now Alliant, product. Developed to meet the requirements of autoloading pistols, such as the 9mm Luger, the powder has been very successful over a wide range of cartridges. A friend at Speer, as I was troubling him about something, confided in me that Speer uses more Bullseye 84 in loading its extensive line of handgun ammunition than all other powders combined. Just before Hercules became Alliant, in the mid-1990s, the company standardized the powder and released it to the reloading public as Power Pistol.

In the canister powder trade, simple competition frequently drives the market. For years those who reload .410 shotshells, mostly for skeet shooting, made do with Hercules 2400, Winchester 296 or Hodgdon H-110. Not to be outdone, as Accurate Arms grew, it introduced 4100. Hodgdon responded with Lil’Gun. Both powders were considered to be .410 specific but were quite suitable for use in some big-bore handgun reloading, as are 2400, 296 and H-110. Alliant countered with a .410 specific powder of its own called 410. It was more efficient than 2400 but considered unsuitable for metallic cartridge use.

Recognizing that competitive shotgunners who reload are constantly looking for bargains in components, a few years ago Alliant decided to market an economy-priced powder, PROMO. It was a volume-for-volume replacement for the company’s fine Red Dot but would be sold only in 8-pound containers. Marketing was generally restricted to large shoots, although retail dealers could order it. PROMO is not as clean burning as Red Dot, nor perhaps as suitable for cold weather use, but it generally produced the same ballistic results as Red Dot. Alliant took further competitive action by introducing Clay Dot, a more cost-effective alternative to Hodgdon’s popular Clays target powder that was both a weight-for-weight and volume-for-volume replacement.

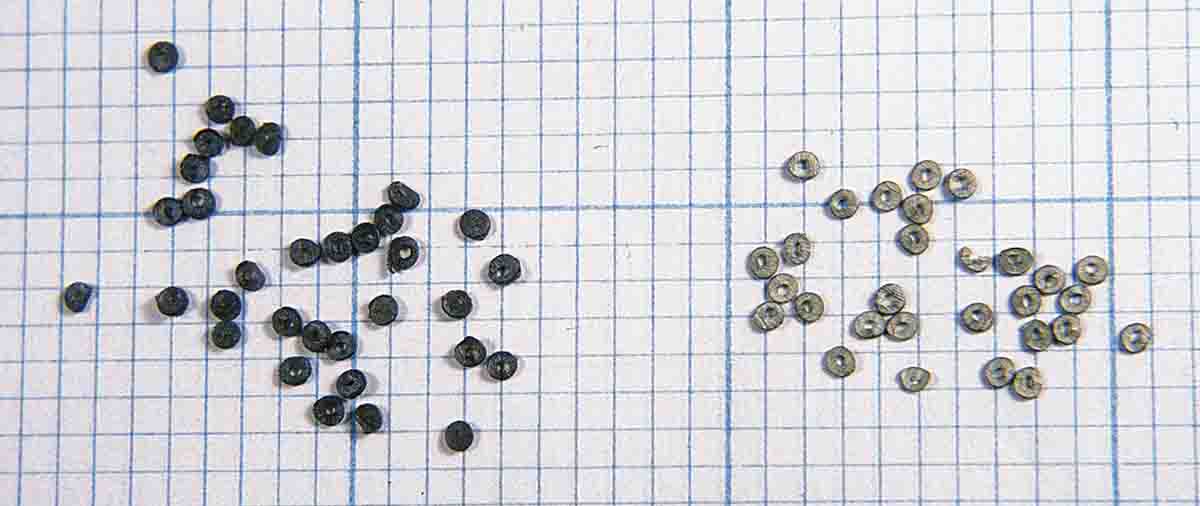

As a result of the popularity of cowboy action shooting, Hodgdon saw an opportunity to introduce a truly different powder, Trail Boss. The powder is ideally suited for low pressure, low velocity, cast bullet loads in the cartridges commonly used in the sport. Its low density precludes double charging and improves shot-to-shot consistency. And, charmingly, it looks very much like the Sharpshooter of a century ago, developed largely to improve performance in the same cartridges.

We’ve also seen existing cartridges improved in other ways. Through a series of proprietary blending and compaction techniques, Hornady has created its Light Magnum line, whereby standard cartridges have been given increased velocities. A rash of new cartridges has been developed lately, all using existing powders. The Winchester Short Magnum (WSM) and Super Short Magnum (WSSM) series are examples, and factory ballistics can be duplicated using available canister powders, assuming the same barrel lengths. That said, Alliant’s newest offering, Reloder 17, is marketed as a new “smokeless powder for short magnum rifles” and “designed for short magnum case capacity.”

So, does this get us any closer to answering Scovill’s question? I think so, although we need to think not in a straight line answer of one or the other, but in a circle. Early on gun, cartridge and powder designers had to work together to produce our first smokeless cartridges. Later on we replaced black powder with smokeless in our existing cartridges. Later still, and now, there are enough powders available that new cartridges could be designed without the need for new powders, although close consultation among the design groups was always important.

As sure as night follows day, though, once a new cartridge emerges, powder manufacturers will try and tailor a new powder for it. And so it goes: New cartridges beget new powders; new powders beget new or improved cartridges.