The Colt SAA

Pearce Shares Personal History

other By: Brian Pearce | February, 26

The Colt Single Action Army revolver is the most recognized, famous and collectible handgun of all time. Its history is fascinating, spanning 135 years and continuing. It has served honorably in the hands of horse soldiers, world war veterans, lawmen and detectives, cowboys, big game hunters, African hunters, explorers, generals, target and exhibition

shooters, average citizens, not to mention bandits and bank robbers. It was present when the western frontier was young, wild and wooly – and eventually laid to rest. In the hands of Hollywood movie actors portraying fictional and nonfictional characters, it has stimulated interest in gun ownership, something we need now more than ever. Before discussing a few of the Colt’s virtues, let me share why it is a special favorite.

Even in my preschool years, I had a fascination with handguns, firing my first at age 3. I looked at and studied every gun I was allowed to handle or shoot, and by age 12 had purchased my first .22 revolver. Practice was daily, and it was put to good use dispatching half-drowned gophers in our alfalfa hay field and barnyard pests ranging from skunks to pack rats. I was hungry to learn everything I could about all good handguns and scraped together enough money to purchase a nice Ruger Single-Six with a 61⁄2-inch barrel and dual .22LR/.22WRM cylinders. Marksmanship skills were improving, and if I would do my part, the gun was capable of taking jackrabbits, ground squirrels, rockchucks, badgers and even unlucky coyotes. I was pushing 14 years old and had developed a strong appetite for hunting big game, including deer, elk, pronghorn and black bear, and really needed a big-bore sixgun.

My five older brothers each had a .357 Magnum, including a Colt, Python, Smith & Wesson Model 28s and others. I had seen them take deer, pronghorn and even elk, and had been shooting all their guns regularly. My opinions of the .357 were somewhat formed; it was a good cartridge, but a larger caliber would likely be better for big game, and it was really noisy (which is an important factor for a field sixgun, as they are often fired without hearing protection). There had to be something better without stepping up to the intimidating (at least for a 13- or 14-year-old shooter) .44 Magnum.

I had made friends with a number of real old-timers, who had been lawmen, ranchers and hunters, and had the opportunity to shoot a number of Colt Single Action Army .45s and .44-40s. I gleaned the knowledge of guns, cartridges and bullets from anyone who would tolerate me, and it quickly became apparent just how respected the old .45 Colt cartridge was by those who had “lived” with one. I listened to stories of it being used to stop a felon’s car, harvest an Alaskan moose in a survival situation and just how pleasant it was to shoot.

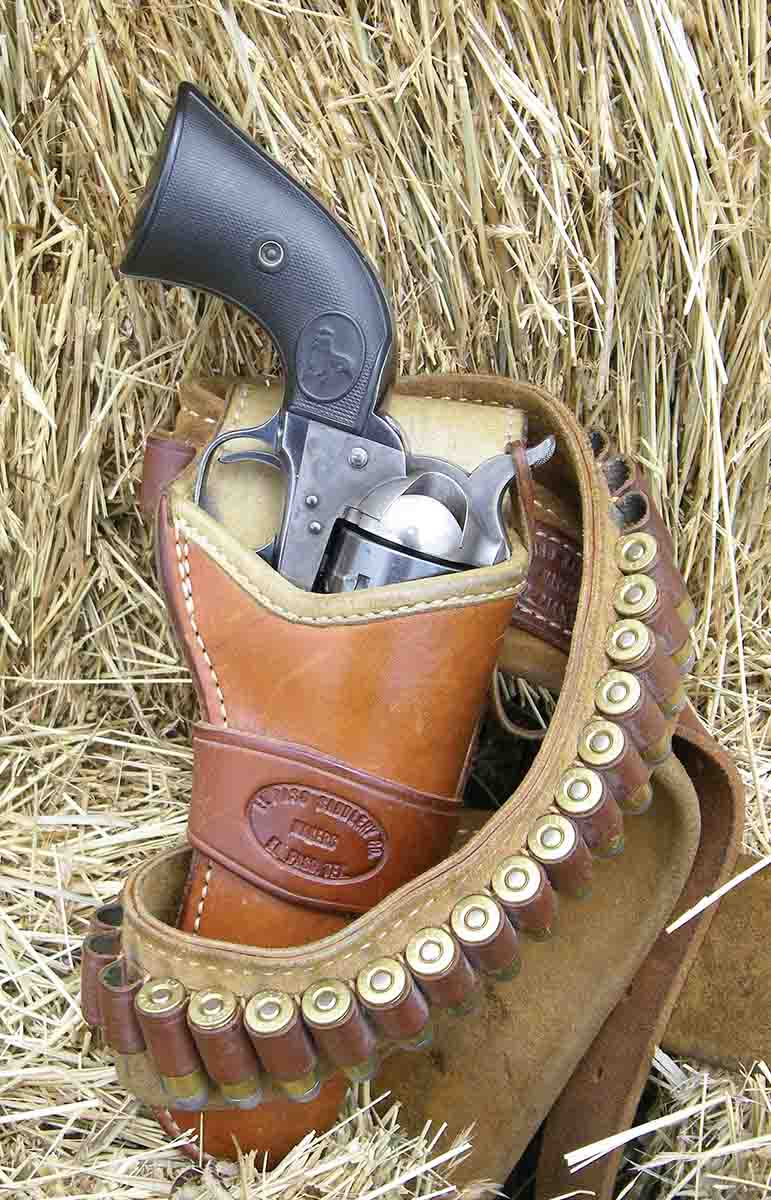

To make matters worse, during this time Dad hired a seasoned ranch hand (who was formerly a saddle maker) to help with spring calving season. Under his pillow the ranch hand kept a beautiful Peacemaker .45 Colt that was housed in a hand-tooled cartridge belt and holster laced with rawhide. The ivory handles had long cracks and were yellowed from age. He was deadly accurate with that gun and would occasionally allow me to fire a few rounds behind the bunkhouse.

I sold a High Standard Double Nine .22, a handmade hunting knife, some antique spurs, a few hides from my trap line and had enough money to purchase a nice prewar Colt Single Action Army .45. It had been made into a flattop frame with an adjustable rear sight and low-profile ramp front blade. It featured one-piece walnut stocks, a 51⁄2-inch barrel and was of unusually

high quality, built by a craftsman from our golden era. It shot very well and was a great gun for a kid living on thousands of acres of range land loaded with game. This was the first gun I began handloading for, took my first big game animal with (at least with a handgun), and it taught many lessons. It also gave me a deep appreciation for the virtues of the Colt Peacemaker and the .45 Colt cartridge.

In the years since, I have owned and fired many dozen Colt Single Action Army revolvers including 1st (1873-1941), 2nd (1955/56-1975) and 3rd generation (1976 through present) guns. While the 2nd and 3rd generation revolvers have their place, for many reasons the prewar versions are the most fascinating. Their quality is noticeably better with the frame properly shaped and the backstrap and trigger guard “flats” being hand-fit and polished to exactly match the frame. The cylinder

flutes are large and beveled, the hammers are of correct width to fill their slot, and the spurs are usually (prior to around 1910) hand-knurled. Trigger guards are gracefully shaped and contoured. By studying the finer details of vintage revolvers, it becomes apparent they were not only a working gun (something they did very well) but also offered artistic quality. While various blueing methods were used during different periods, it was attractive and the molten case colored frame and hammer were stunning.

The Colt SAA revolver was not just dreamed up at the factory by a couple of engineers,

but rather was the result of decades of building fighting guns used in a variety of skirmishes, including the Civil War. Those experiences, including much feedback from battle-worn soldiers, law enforcement and frontiersmen, led to the development of the SAA, which was designed with very little fat or excess weight. Even with a 71⁄2-inch barrel, a .45 Colt revolver tips the scales at 39 ounces, while the 43⁄4 inch is 36 ounces. This is heavy enough for steady offhand shooting, yet light enough to wear in a hip holster for long hours. The Peacemaker’s weight, size and superb balance are difficult to improve upon as a practical field or working sixgun and, in this respect, remains the pinnacle of all single actions.

A fascinating aspect of prewar revolvers includes the various applications for which they have been used. For instance just holding a .45-caliber “US” cavalry revolver takes me back to the fascinating (and tragic) history of the Indian wars. Perhaps it was carried by one of Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s troopers at the Battle of the Little Bighorn or carried up San Juan Hill beside the flamboyant Teddy Roosevelt. Perhaps it was pulled from “retirement” and put to battle in the Philippines when the newly adopted .38-caliber Colt double-action revolver failed to stop drug-hyped warriors. As predicted the proven .45 Colt sustained its reputation for stopping fights with a single shot, which saved many U.S. soldiers’ lives.

Civilian guns are often more interesting, as these were the ones ordered by the town sheriff, Texas or Arizona Rangers, cowboys, townsmen or Indian policemen. In this form it was available in many cartridges, barrel lengths and finishes. The most common calibers included .32 WCF (.32-20), .41 Colt, .38 WCF (.38-40), .44 WCF (.44-40) and .45 Colt, with the standard finish being blue with case-colored frame and hammer. For those wanting to dress up their sixguns, ivory and pearl stocks with or without carvings were offered (as well as other exotic materials), and for a relatively small sum, factory engraving was available.

Another gun I have had the pleasure of shooting is a “long flute” .45 (manufactured 1913-1915) with a 71⁄2-inch barrel that was used to rob a Montana bank. When the hold-up turned into a shootout and the cowboy was killed, the sheriff wound up with the gun, holster and cartridge belt. This is one of the finest shooting SAAs I have ever fired and is a reminder that the “Old West” was really not that distant, as this gun was made the same year as my father, who is still living.

There is also a “US” cavalry gun that was almost certain to have been carried by Roosevelt’s Rough Riders up San Juan Hill. Naturally it is a 51⁄2-inch version but is in unusually good condition. And, yes, it shoots very well, but more importantly, it is a piece of history that can almost be “felt” when held and fired.

Others that will only be briefly mentioned include a 43⁄4-barreled .45 Colt that was stained (actually pitted) with the blood of its owner, a sheriff, from a wound sustained in a gunfight. And there is a .32-20 WCF that was used by a sheepherder to kill coyotes, as well as black bears that had developed a taste for mutton. I have also had the pleasure of using the Harold Croft and Elmer Keith experimental “M-2” revolver, a lightweight outfit that was converted to .44 Special and outfitted with adjustable sights and a specially designed grip frame. And there is Dick Casull’s (of .454 Casull fame) 71⁄2-inch barreled .44 Magnum with special heat-treating methods that allowed it to safely handle the heavy load in spite of being more than a century old.

Besides having a colorful history, the Colt SAA has served me well in many different applications. In addition to being used to dispatch everything from rattlesnakes to porcupines, “working” guns helped account for a number of big game, including deer, elk, black bear and mountain lion. And while they are not generally thought of as a target arm, the Colt can be accurate.

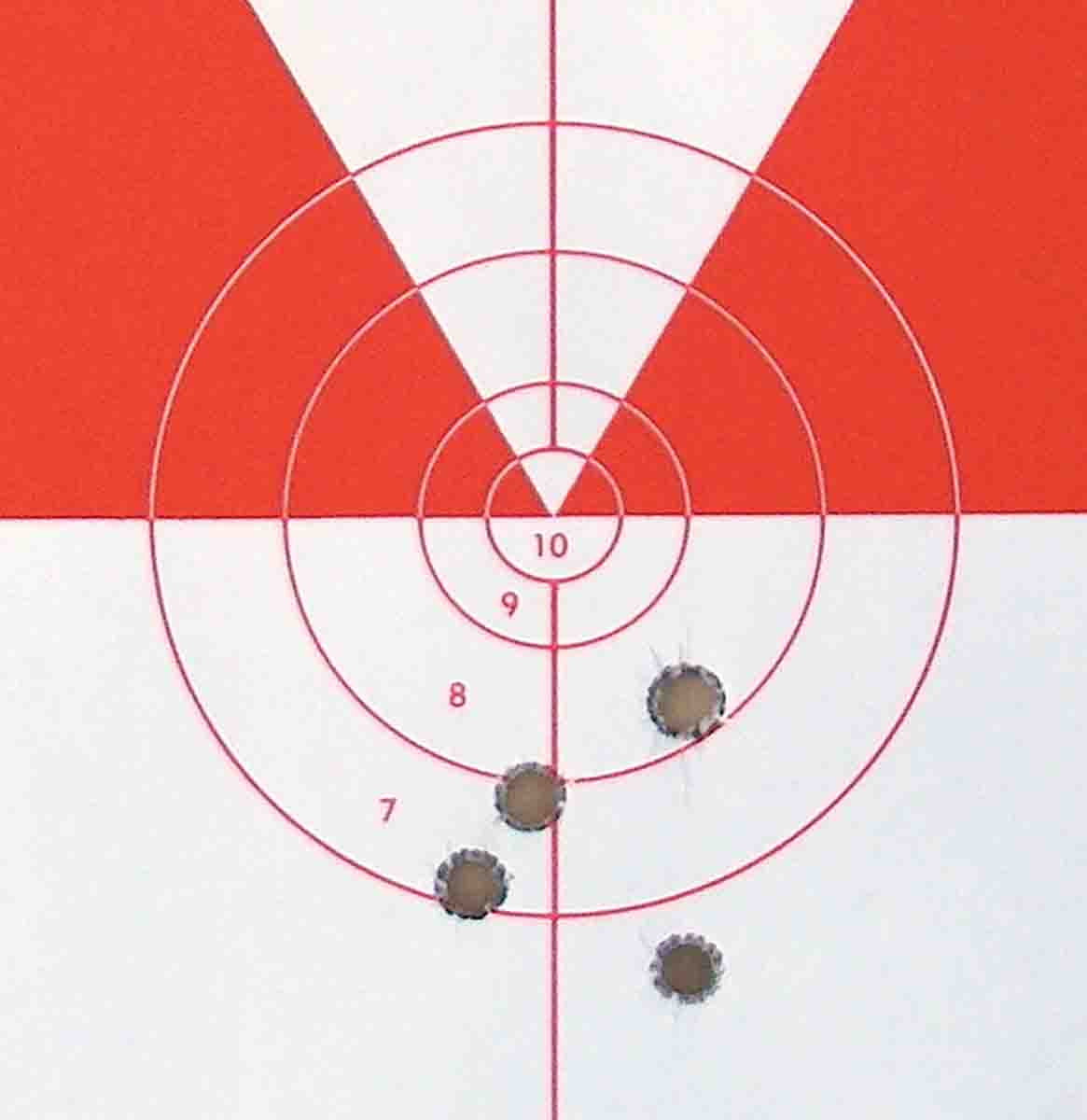

At age 17, I attended a turkey shoot being sponsored by a police organization. Upon signing up, the sergeant in charge was extremely rude, but this was my first such event and some fundamental questions were asked. At any rate, I stepped up to the “line” and won several turkeys in a row, using my brother’s Smith & Wesson K-22. The sergeant was nothing short of angry, as he was losing to a wet-nosed kid. He then announced that all contestants were required to use a centerfire handgun, which he thought would disqualify me. I retrieved a Colt SAA .45 from the pickup and proceeded to take the turkey from the sergeant again, with him using a custom-built target bull-barrel Smith & Wesson Model 10 .38 Special. He then announced that six turkeys was the maximum that anyone could win, and I was out! This event is not mentioned to indicate I am a great handgun shot, but rather the rude sergeant was just really bad! Nonetheless, the Colt was capable of 1- to 11⁄2-inch groups or less at 25 yards from a sandbag rest.

When working range cattle, a .44 Special or .45 Colt stoked with cast bullets on the hip is comforting, as things can get dangerous in a heartbeat. My Colts have been carried in threatening circumstances, or what is commonly known as self-defense, with complete confidence. In spite of some thinking that an automatic pistol with multiple 17-round magazines is necessary for such work, the truth is that an individual who really knows how to use a single action is well-armed and capable of coming out on top in a gunfight. I enjoy perforating aerial targets, precision long-range shooting and draw and hit as practical practice sessions.

Favorite Guns,

Calibers and Loads

As discovered in my early teens and in the decades following, the .45 Colt performs better on game than its “paper ballistics” (measured in foot-pounds) indicate. A 250- to 260-grain cast or lead bullet of correct design and driven around 900 fps will cut through deer, elk and black bear on broadside shots. And being of .45 caliber, the bullet opens a respectable wound channel, especially bullets with a substantial meplat and full-caliber front driving band. So loaded the cartridge is best described as reliable and is a more effective cartridge than the .357 Magnum. There are other important reasons to appreciate this old cartridge and include its relatively low pressures of 14,000 psi, which results in lower muzzle blast and noise (greatly appreciated by many experienced shooters), little barrel erosion and long case life.

My standard .45 Colt handload for smokeless-era Colt Single Action Army revolvers is cast bullets from Lyman mould 454190 that weigh 255 to 260 grains and are profiled essentially the same as vintage ammunition. Using 6.0 grains of Alliant Red Dot powder or 7.1 grains of Winchester 231 powder will essentially duplicate the 108-year-old factory loads from Remington and Winchester that contain 250- and 255-grain bullets, respectively. Either Federal 150 or CCI 300 Large Pistol primers should be used. Velocity is around 860 fps from a 51⁄2-inch barrel. Bullets are roll crimped over the ogive for an overall cartridge length of 1.580 inches.

When I want a load that delivers a bit more shock to game, the old Keith bullet, Lyman mould 454424, at 255 grains is employed. It can be used with the above powder charges, but if more velocity is desired, 9.0 grains of Hodgdon Universal Clays will achieve around 950 fps from most revolvers and is a respectable hunting load.

For post-World War II Colts (and prewar guns with appropriate steels), the RCBS mould 45-270-SAA cast bullet is superb. It is an improved Keith design intended specifically to maximize the performance of Colt SAAs. From most alloys it weighs between 280 and 285 grains. Either 7.5 grains of Hodgdon Titegroup or 10.5 grains of Vihtavuori VV-3N37 will produce between 950 to 1,000 fps from a 51⁄2-inch barrel and are proven loads on game.

The .44 Special is a great cartridge in the Colt SAA, but I prefer to handload to enhance its power and performance. The problem is that in the pre-World War II era, there were only 507 Colt SAAs produced in .44 S&W Special, which usually command a premium from collectors – and do not belong in my hands that would put them to work. Due to this limited availability, I have converted a number of SAAs (that were previously altered in some fashion) to .44 Special, which make great “shooters” especially when chambers are held to minimum tolerances and line-bored. This caliber has been popular in the post-war SAAs, and handloads offered herein are safe for guns of any generation.

There are many great .44-caliber bullets, but the one I rely on most is the 250-grainer cast from Lyman mould 429421. Driven with 8.0 to 8.2 grains of Alliant Power Pistol, velocities are just under 1,000 fps from most revolvers with a 43⁄4- to 51⁄2-inch barrel. On those occasions that more velocity is desired, 16.0 grains of Alliant 2400 will produce around 1,181 fps from a 71⁄2-inch barrel or 1,140 fps from a 43⁄4-inch gun.

I very much enjoy shooting .44-40 and .38-40 Colt SAA revolvers, and while they are good and effective cartridges, neither can match the power of the .44 Special or .45 Colt and therefore are viewed as somewhat nostalgic.

Although somewhat specialized, the .32-20 is a favorite small game hunting cartridge. Everyday loads include the 116-grain cast bullet from Lyman mould 311008, sized .312 inch and pushed 950 fps (71⁄2-inch barrel) with 4.0 grains of Hodgdon Universal Clays. For long-range jackrabbits, a 116-grain gas check bullet (Lyman mould 311316) is driven 1,450 fps using 12.5 grains of Hodgdon H-110 and capped with a Remington 71⁄2 Small Rifle primer that produces around 28,000 CUP. (Using this primer will help prevent it from “flowing” into the Colt’s rather large firing pin hole and tying up the gun.)

Other favorite guns must be discussed generally as to caliber and barrel length. Guns with 71⁄2-inch barrels are easy to shoot well due to additional barrel weight and longer sight radius, offer instinctive pointing virtues and are well suited to resting on the hip while in the saddle. Unfortunately they are on the long side for everyday hip carry, as they are hard to sit down with or to slide in or out of a vehicle. For this reason, everyday working guns are usually fitted with 43⁄4- or 51⁄2-inch barrels and are chambered in .44 Special or .45 Colt. In spite of critics feeling that the 51⁄2-inch version is a compromise, it is an excellent all-around length and was the length the U.S. military settled on after years of service. Nonetheless, I find the 43⁄4-inch barrel the handiest and is the length used the most.

The SAA used most is chambered in .45 Colt with a 43⁄4-inch barrel, sports carved ivory stocks and is more than 100 years old. The action is carefully timed and tuned, has been fitted with modern springs, bolt, etc. The forcing cone is carefully cut, and the trigger pull is crisp and clean. It has had in excess of 15,000 rounds fired through it since being in my possession. It is often worn to town stuffed casually in the waistband, where its sleek profile and fixed sights don’t snag on clothing and such. In spite of its age, I do not feel handicapped when taking a buck or a beaver.

Virtues of the Design

and Reliability

I have read many times that the Colt Single Action Army is “a gunsmith’s friend” or is “prone to breakage.” It certainly can, but with modern springs (hand, bolt/trigger spring) it is far less prone to breakage as long as the shooter understands the lockwork and how to use the gun properly. And many Colts are poorly timed (due largely to parts being improperly replaced), which causes undue stress to the lockwork and often results in premature breakage. I have guns that have been tuned and properly timed, then more than 10,000 rounds fired through them without a single failure or breaking of parts. At this point, just like maintenance of a car, trigger/bolt and hand springs as well as the bolt should be replaced. If parts do break, they are easy and inexpensive to repair and/or replace. (Wolff springs are available through Brownells at 1-800-741-0015 or you can visit online at: www.brownells.com.

To further illustrate the reliability of the old Colt, during the 1889, 1890, 1891 NRA Wimbledon and Bisley Common, Colt SAAs won by far the most prizes but were also subject to firing more than 60,000 rounds without a single mishap (misfire or breakage). Again, with modern steels and springs, the chance of breakage is even further reduced.

In today’s environment with little frontier left, comfortable homes, air-conditioned cars, less horse travel, less really hard work, few realize just how tough and durable the Colt SAA really is. The action is well protected from dirt, dust and moisture and when dirty, still continues to function as well or better than most revolvers. The .25-inch base pin extends through the solid frame and cylinder, which results in a gun that can take a real beating without damage to the crane or misalignment of the cylinder (which is common with many double-action revolvers). Another virtue of the design is that they can still be fired with a number of broken or missing parts! I have restored many Colts that were literally beat to death from use and abuse on the frontier and in Hollywood movies. A double-action revolver would have been toast, but with new parts, the old Colt can become usable again.

Safety Tips

Before using any prewar Colt Single Action Army revolver, it should be determined to be in safe shooting condition by one who is qualified. Guns below serial number 192,000 are intended for black powder, while guns above that number are built with better steels, making them suitable for smokeless powder loads.

Even though there is a hammer “safety” notch, it should not be trusted, as it and/or the trigger sear can break causing an accidental discharge when dropped or bumped. Always carry the Colt SAA (as well as clones, old model Ruger Blackhawk revolvers, Freedom Arms Model 83s or similar actions) with five cartridges in the cylinder and an empty chamber under the hammer.

We live in a day and age when many expect others or the government to protect and take care of them. Perhaps the Colt SAA should serve as a reminder of generations past who knew how to take care of themselves.