300 Holland & Holland Magnum

Happy 100th Birthday!

feature By: Layne Simpson |

The Super 30 Magnum Rimless was introduced by the British firm of Holland & Holland (H&H) in 1920. At the time, the shop was building high-grade stalking rifles in 375 Magnum on actions built at the Mauser factory in Oberndorf, Germany, and the same action was used for building rifles chambered for the Super 30. Why it was given a milder shoulder angle is lost in time, but it was likely due to the fact that doing so made cartridges feed more smoothly in a magazine rifle than had the 375 H&H case been simply necked down for a .30-caliber bullet. Also, the 375 H&H case necked down with no other change would have resulted in a rather short neck.

The Super 30 was offered in Flanged Nitro Express variation for double rifles and Rimless Nitro Express for magazine rifles. Both were loaded with cordite, an early smokeless propellant of high nitroglycerine content formed in strands, or “cords,” of a length that often reached from the web of the case to the beginning of its shoulder. Linen thread was sometimes used to hold a bundle of strands together, and that eased manual insertion into the case prior to its shoulder and neck being formed. In addition to being quite erosive on barrels, cordite was extremely temperature sensitive, and since the 30 Super would surely be subjected to the tropical climates of India and Africa, pressure and therefore velocity were intentionally held quite low. The 150-grain bullet seated atop 58 grains of cordite had a velocity rating of 3,000 feet per second (fps). Bullets weighing 180 and 220 grains pushed by respective cordite charges of 55 and 49 grains exited the muzzle at 2,700 fps and 2,350 fps, respectively. In other words, the big British cartridge delivered the same velocities as American loadings of the 30-06 Springfield.

When the 30 Super immigrated to America in 1925, it became known as the 300 Holland & Holland Magnum, so in the minds of American hunters, it is celebrating its 100th birthday this year. The British cartridge became almost all it could be when the Western Cartridge Company began loading it with 180- and 220-grain bullets at respective velocities of 3,060 and 2,739 fps. The 180-grain load was eventually reined back to 2,920 fps. Match ammunition with a 180-grain full-patch, boat-tail bullet at 2,920 fps was added. Not to be outdone, Remington quickly joined the chase with big-game and match loadings.

It should be noted that the 300 H&H was not the first magnum-capacity cartridge to be introduced to hunters in America. Charles Newton, who founded the Newton Arms company in 1913, offered rifles chambered for the 30 Newton, and it was loaded by the Western Cartridge Company until the 1940s. Unfortunately, due to the limited production of rifles chambered for the cartridge, not many hunters were aware of it. I find it interesting that the powder capacities of the 30 Newton, 300 H&H Magnum and 300 PRC introduced by Hornady in 2018 are pretty close to the same. Like the 30 Newton, the 300 PRC does not wear a belt.

For quite a few years, the 300 H&H was mostly used by well-heeled sportsmen who traveled far in search of game and could afford the price of an English-built rifle. A best-quality Holland & Holland Magazine Rifle on the Mauser action sold for 35 Guineas in London and $320 in New York. The fate of the cartridge began to change in 1935 when Ben Comfort of St. Louis, Missouri, used a custom rifle in 300 H&H to win the prestigious 1,000-yard Wimbledon Cup match at Camp Perry, Ohio. Built by Griffin & Howe on a highly modified 1917 Enfield action, the rifle had a 30-inch bull barrel made by Winchester. The ammunition used by Comfort was loaded by Winchester. A photograph of him with his rifle and big silver trophy cup soon appeared in a widely circulated Shooting Holidays news journal published by Winchester in those days.

Griffin & Howe had been offering big-game rifles in 300 H&H prior to Ben Comfort’s big win, but they were rather expensive when compared to the price of a Winchester Model 54 or Remington Model 30, both available in 30-06 at the time. Fate smiled again when Winchester introduced the Model 70 in 1937, and the 300 H&H was among its nine original chamberings. The 300 H&H was available in three variations: Standard Rifle with a 26-inch barrel, Target Model with a medium-heavy 24-inch or 26-inch barrel and, as if to capitalize on Ben Comfort’s win, the Bull Gun with a heavy 28-inch barrel. Interestingly enough, the tiny 22 Hornet chambering was introduced in the Model 70 during the same year, but that’s a story for another time.

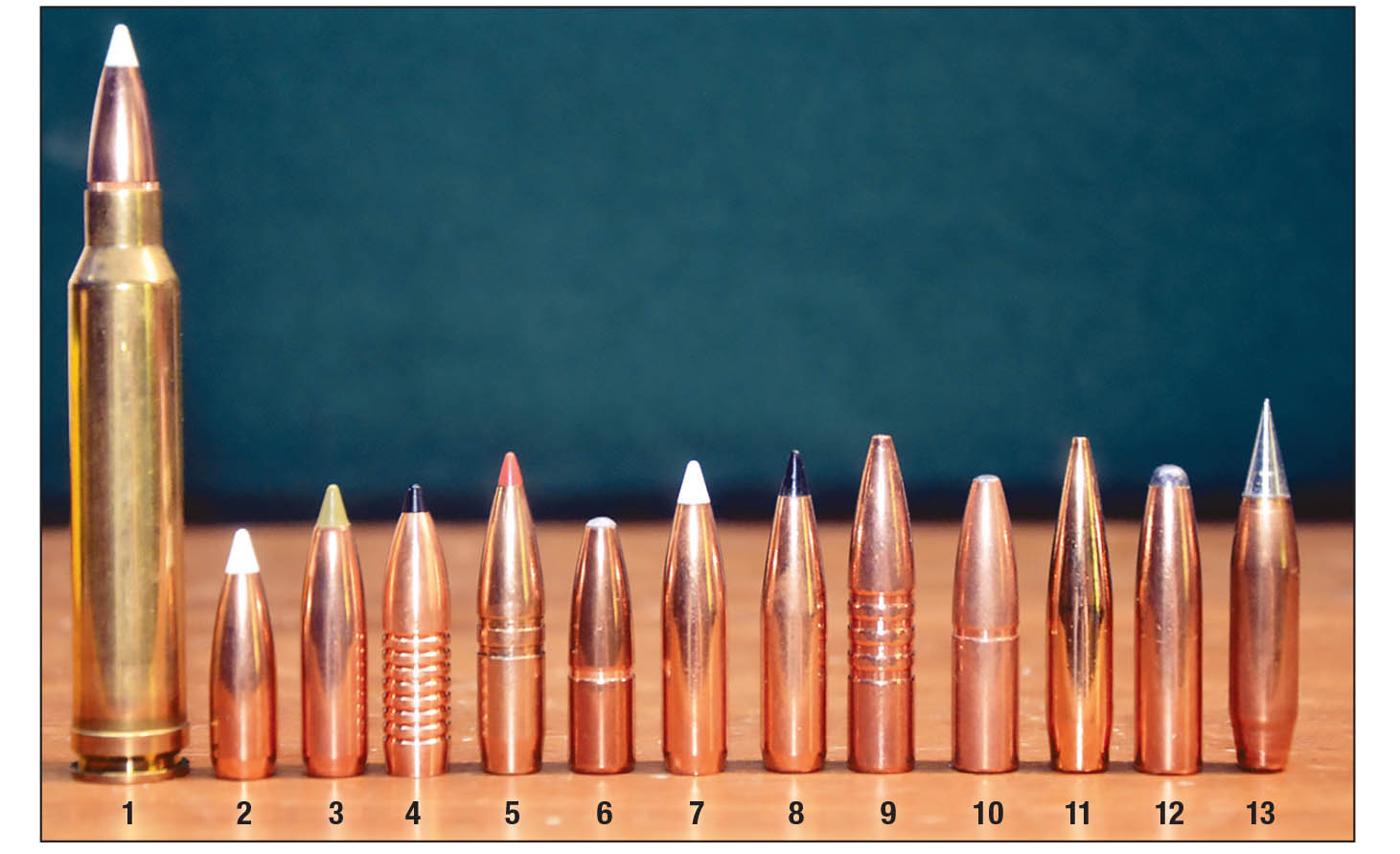

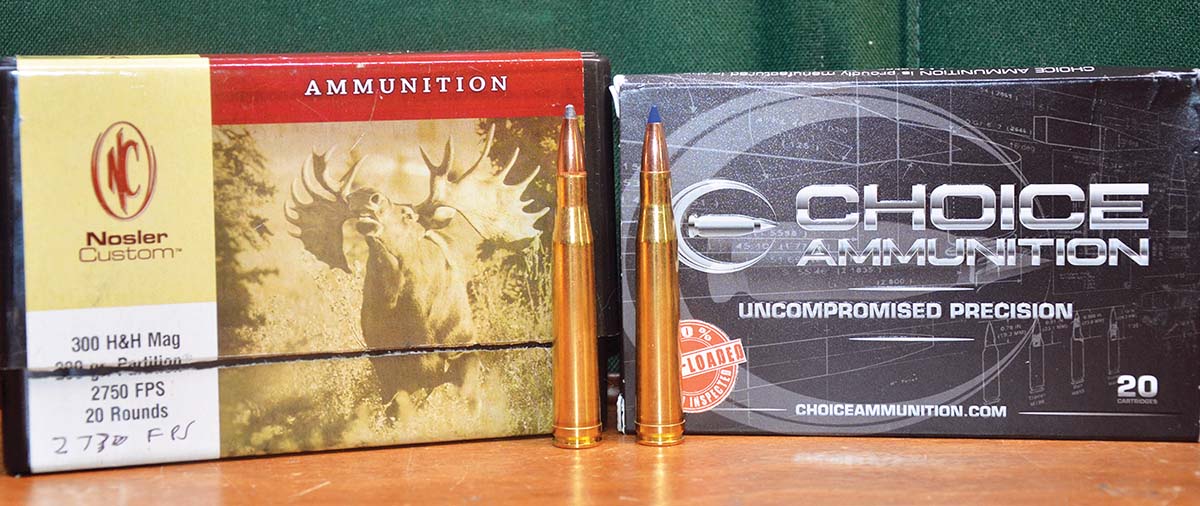

The first rifle in 300 H&H that I owned was on a modified 1917 Enfield action, and while I would like to say it was built by Griffin & Howe and it center-punched tacks, its builder was unknown, and it was not very accurate. Next was a Model 70 that I hunted with for several years before giving it to a friend. It was one of the first factory rifles I owned that would consistently shoot three bullets inside an inch at 100 yards. As a bonus, it digested, without a single whimper, the maximum charge of H-4831 shown on page 159 of the Hodgdon’s Data Manual Number 23. Maximum velocity clocked by Hodgdon’s 24-inch test barrel was 3,013 fps, and the same charge behind the Nosler 180-grain Partition was 87 fps faster in my rifle, probably due to its longer 26-inch barrel. Winchester cases were long-lived, seldom needed trimming, and I don’t recall discarding a single one due to an expanded primer pocket.

Through the decades, I have enjoyed using rifles in 300 H&H Magnum on several hunts, and one will always be at the very top in fond memories. The planning for it began in 2007 when Bob Nosler mentioned that the company would be celebrating its 60th anniversary during the next year, and we should celebrate with a hunt in the Yukon. The favorite rifle of Bob’s father, John A. Nosler, was a Winchester Model 70 in 300 H&H Magnum, and the failure of lead-core bullets on a mud-caked bull moose prompted him to design the Partition bullet. Being aware of this, I suggested to Bob that we use Model 70s in 300 H&H, and since his dad’s favorite hunting garment was a Filson Mackinaw Cruiser, we left our synthetic fabrics back home and wore the same. Bob’s son, John R. Nosler, who now heads the company, would also be on the hunt, and he managed to round up a couple of Model 70s in 300 H&H for Bob and me to use. As a bonus, he also located just enough 180-grain Partition bullets made by his grandfather during the 1940s for me to zero the Model 70 and to use on the hunt.

Soon after returning from that hunt, I began to itch all over for a rifle in 300 H&H Magnum and turned to Lex Webernick of Rifles, Inc. for the cure. After blueprinting my Model 700 action, Lex fitted a Lilja 26-inch, three-groove, stainless steel barrel with a 1:10 twist. He also replaced the aluminum bottom metal with Sunny Hill steel from Brownells. All metal received a black CERAKOTE coating. Lex then pillar-bedded the action in an Ultra Walnut stock made by S&K Industries of Lexington, Missouri. Remington used stocks made by that company for many years, with Ultra Walnut stocks reserved for high-grade rifles and shotguns. At first look, the stock of my rifle has the appearance of any other stock of nicely figured walnut, but a top or bottom view reveals two thin layers of carbon fiber sandwiched between three thicker layers of walnut. Most who have examined the rifle through the years did not notice that until it was pointed out. The stock has the warmth and beauty of high-grade walnut, and yet according to technicians at S&K, it is comparable in strength and warp-resistance to a multi-layered laminate, but without the weight. Remington eventually purchased S&K Industries. A 3-shot group fired by Lex with Nosler 180-grain AccuBond bullets included with the finished rifle measured just under a half inch. The rifle’s first hunt would be for elk in New Mexico, and on the fifth day, I used the same load to take a good bull at 265 yards. Barrels chambered for magnum cartridges don’t last forever, so through the years, I have not developed a great many loads for the rifle.

From the very beginning of Model 70 production in 1937 to its end in 1963, the 300 H&H did not rank among its best sellers, and the introduction of the 300 Winchester Magnum in 1961 drove the final nail in its coffin. Even so, it was more a matter of “new has to be better” than any difference in potential performance. The Nosler Reloading Guide has net water capacities of various cartridges measured with bullets of various weights seated. The biggest difference shown in favor of the 300 Winchester Magnum is 3.6 grains for 180-grain bullets, and the smallest difference is 0.4 grain for the 200-grain Partition. For cases of that size, such minor differences in net capacity have an insignificant bearing on velocity, assuming the two cartridges are loaded to the same chamber pressure and fired in barrels of the same length. Nosler shows the 300 Winchester Magnum as 100 fps or so faster with all bullets except for the 220-grain Partition, so the Winchester cartridge was obviously loaded to slightly higher chamber pressure than the 300 H&H.

Contrary to what is often written, the 300 Holland & Holland Magnum does not require a “magnum” action. The Winchester Model 70 had the exact same standard-length action for it and all other cartridges for which it was chambered. I have rifles in 300 H&H and 300 Winchester Magnum on standard-length Remington 700 actions. On the other hand, I have a Ruger Model 77 Magnum, and it does have a “magnum” action for the longer 416 Rigby. More accurately stated, the 300 H&H is too long for the standard-length 98 Mauser action unless it is modified to accept it, as was done by several companies in the past.

.jpg)

.jpg)