A Pair of .25s – Make That Three

These Quarter-Bore Wildcats Are Quick, Mild and Useful!

feature By: Wayne van Zwoll |

During the early days of automobiles, while the makings of unimaginable war simmered in Europe, stateside rifle enthusiasts A.O. Neidner and F.J. Sage concluded a case the size of the .30-40 Krag’s was perfect for a hot .25 cartridge. They had in mind just the rifle for it.

Like his father, who’d eventually lost interest in his tannery, John drifted to gunsmithing. He was in a good place at a good time. Rails had just joined at Promontory Point, 50 miles from Ogden. By 1878, when he turned 23, muzzleloaders had given way to cartridge arms. Although he had no drafting tools, and his main shop fixture was a foot lathe, ox-carted from Missouri, John wanted to build a rifle. He sketched the action and hand-forged its parts, filing them to dimension. Then he wrote Schoverling, Daly and Gales in New York: “Please tell me how to patent a gun.” John Browning filed for his first patent on May 12, 1879.

His father died soon thereafter, leaving John the head of two households. With brothers Matt, Ed, Sam and George, he built a 25x50 shop on a 30-foot lot at the edge of Ogden’s business district. Frank Rushton, an English gunmaker touring the West, helped the youths tool up, turning that shop into a factory. Ed ran the mill. Matt made stocks. Sam and George rough-filed receivers, John finished the parts, and assembled each single-shot rifle. At $25, it sold briskly.

Alas, three months into production and just a week after opening a retail counter, burglars stole everything of value, including the prototype rifle. The Brownings persevered, finishing as many as three rifles a day. John designed a second dropping-block action. By 1882, he’d sketched and then built a repeating rifle. Awaiting that patent, he started on another.

While its 1873 repeater in .44-40 was hugely popular, Winchester had nothing to match the power of Sharps and Remington single-shots. So, when in 1883 Winchester salesman Andrew McAusland came upon a second-hand Browning rifle, he gave it a close look. Then he sent it to New Haven and company VP Thomas Bennett.

Bennett immediately embarked on the six-day rail trip to Ogden. He found a modest shop run by striplings barely out of their teens. But Oliver Winchester’s son-in-law was no fool. “How much for your rifle?” he asked John. One rifle? No, the rifle. Winchester would buy all rights.

Bennett was surely stunned by Browning’s reply: “Ten thousand dollars.” An enormous sum in 1883 – and this from a country bumpkin! Bennett offered eight and paid a $1,000 deposit. Weeks later, having sent the remaining $7,000, he had to remind John to stop making what was now Winchester’s rifle. It soon appeared as the Model 1885. Browning’s “High Wall” action was slimmer than the equally stout 1874 Sharps and stronger than the 1873 Springfield. A subsequent “Low Wall” version for small cartridges gave easier breech access. Winchester’s 1885 was listed in most popular chamberings, ranging from .22 rimfire to the big bores serving buffalo hunters.

Discontinued in 1920, the Model 1885 was revived by Browning as the Japanese-built B-78 and produced from 1973 to 1982. It returned in centerfire form as the Model 1885 from 1985 to 2001, then under the Winchester banner beginning in 2003.

Mine was a gift from a friend. An early High Wall, it is much altered but in fine working order. Notably, the barrel is bored for the 25 Short Krag.

This .25’s case (from the 30-40 Krag, for which many 1885s were chambered) measures 2.750 inches, base to mouth – at least, that’s what my rifle likes. Nominal length of the 30-40 is 2.314 inches. Shoulder angle and location are the same.

You might well ask: How deep does the 25 Short Krag bury the 25-35, introduced in the Winchester Model 1894 rifle in 1895? Well, the Krag holds more powder. Both hulls are rimmed, but the Krag’s base is .545 in diameter, the 25-35’s .506. The .25 Krag’s length to mouth is .232 greater. Length to the shoulder is 1.725 inch for the Krag, 1.380 for the 25-35. Both cartridges, incidentally, rank among some of the first smokeless centerfire offerings stateside.

At a glance, I expected spunky loads in the 25 Krag to match the enthusiasm of the .250 developed around 1913 by the brilliant Charles Newton. Savage stoked that cartridge to send 87-grain bullets from its Model 99 lever rifle at 3,000 feet per second (fps), blinding speed in those days. Newton was evidently willing to forego the Madison Avenue moniker of 250-3000 to launch 100-grain bullets at 2,800 fps. Eventually, the 87-grain load was dropped; the cartridge endures as the 250 Savage. Handloads in bolt rifles can improve markedly on the velocity and accuracy of 250 factory loads.

Because commercial loads for the more capacious 257 Roberts (adopted by Remington in 1934) were held to mild pressures, the 25 Krag seemed poised to upstage those as well.

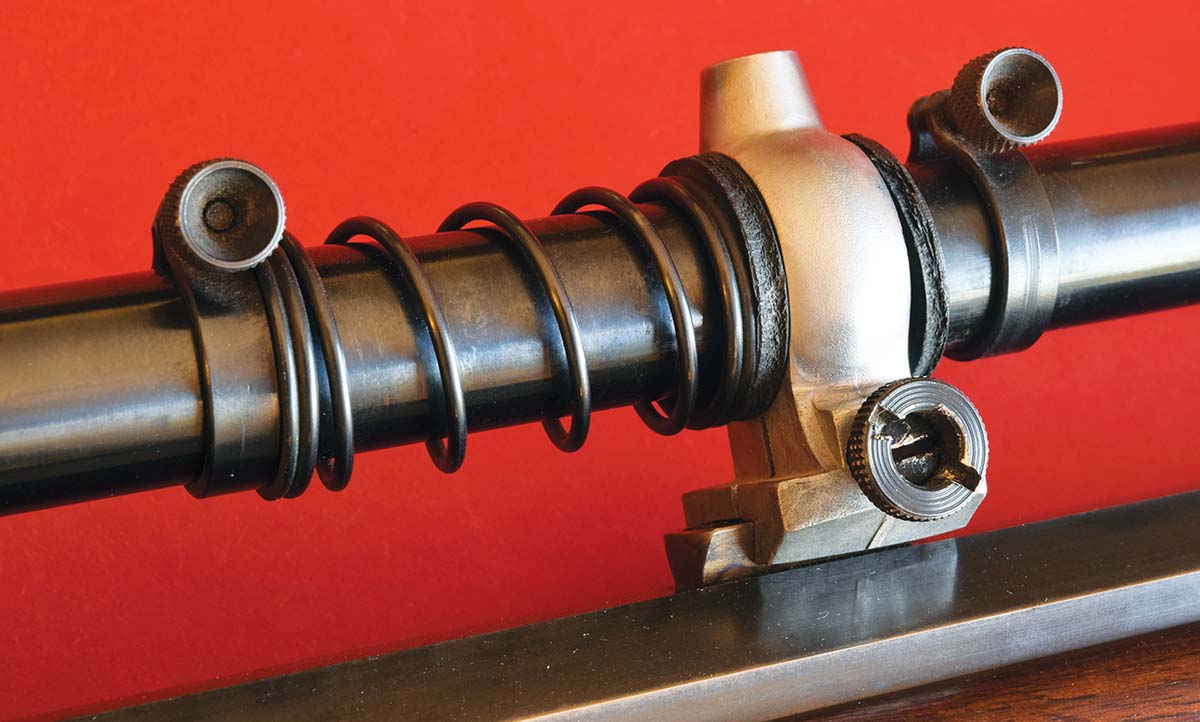

The heavy 28-inch octagon barrel of my High Wall carries a 12x Litschert scope with the external adjustments of its day. This optic pairs nicely with the rifle’s weight and dimensions to suit it for prone shooting in ’chuck pastures with quick, lightweight bullets but I’ve long leaned on .25s for their performance on heavier game. They handily accelerate the 100-grain bullets that seem a practical limit for traditional 6mms. For big deer, Nosler’s 110-grain AccuBond gives a clear edge to .25-bore cartridges over 6mms of equivalent case capacity.

Using powders as slow as IMR-4350 in the 25 Krag, I found 87- and 100-grain bullets preferred faster fuel (Table 1). Easily overtaking the 250 Savage with powders in the IMR-4895 W-760 burn range, this wildcat eclipses even modern 257 Roberts +P loads. Predictably, it falls well shy of catching the 25-06, a Remington cartridge since 1969. (As early as 1909, Charles Newton experimented with .25s on the 30-06 case. So did many other wildcatters. The 25-06 endured as a wildcat cartridge longer than it’s been commercially loaded!)

While rambunctious loads for the 257 Roberts and the 257 Ackley Improved can trump the 25 Krag downrange, their rimless cases aren’t as neatly suited to dropping-block single-shots as the Krag’s rimmed hull.

In repeating rifles, the Roberts is still imperfect. It derives from the 7x57, a fine option in the Mauser 1898 actions for which it was designed. It’s a mid-length cartridge, an odd fit in the long and short actions of modern sporters fashioned, respectively, for the 30-06 and 308 Winchester and kin. Long actions wonder why they’ve not been fed the frothier 25-06; short magazines refuse the Roberts unless bullets are seated quite deep.

Having shot deer with the 257 Roberts, and with the 243 Winchester and the 244 Remington, I’m sweet on all three. What long intrigued me was a .243-length rimless .25. Necking the .243 up yields the 25 Souper, a wildcat I’d like to have claimed. Its origin is unclear; surely it occurred to some clever handloader shortly after the .308’s 1952 debut.

In his Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders (Vol. I, 1962), P.O. Ackley described the 25 Souper with modest enthusiasm as “… quite similar to the Improved 250/3000 …. It is made by necking the 308 Winchester case to .25 caliber with no other change.”

Field & Stream shooting editor Warren Page may have written the first text I read on this round. He pointed out the ease of forming cases: an expander plug bumping the 243 Winchester out to accept 25-caliber bullets. Necking down the 308 Winchester is the long route.

For decades, the 25 Souper stood patiently in line behind my other rifle projects. Then ace gunmaker Charlie Sisk came up with a short Remington 700 action and a 24-inch Lilja barrel with 1-in-10 twist. He squared the bolt face, lapped the lugs and trued the receiver face and barrel shank. Then he installed one of his heavy .300 recoil lugs. Charlie machines these from stainless steel, then bores and surface-grinds them to fine tolerances.

With Brownell’s Acraglas Gel, Sisk bedded the barreled action in a Hi-Tech Specialties stock from Mark Bansner. “My father plugged a radiator leak on an old Farmall tractor with Acraglas,” he explained. “It’s held for more than 20 years. Acraglas is good stuff.”

Adding a Timney trigger and a Swarovski 3-9x36 in one-piece Talley alloy mounts, I was delighted with the fine balance and eager pointing qualities of this 7-pound rifle. Mild handloads quickly gave me a 200-yard zero. A few shots over my Oehler sky-screens, and I hiked charges to leave the 250 Savage and 257 Roberts behind. Hornady 87-grain spitzers clocked over 3,330 fps with no signs of untoward pressures. Exceeding 3,100 with 100-grain Sierra and Nosler bullets was no harder. Best news: These fast-stepping loads and 110 Bergers driven to 3,145 fps all shot into .85 inch (Table 2). Duly impressed with Charlie’s gunsmithing, I could hardly have snared a better deer/pronghorn rifle. On its first range outing, this 25 Souper punched seven three-shot groups that measured under .75 inch. I didn’t clean the barrel at the bench or let it cool more than a short minute between shots. While most powder charges nudged recommended maximums, there were no sticky bolt lifts or loose primers.

Bartt manufactures his own AR receivers, locking upper and lower with a ball-in-groove arrangement. The integral guard is open enough for glove use without looking odd. Generous fire controls nix fumbling. The take-down pin is finger-friendly for tool-free disassembly. Stainless magazines with .020-inch walls feed cartridges to snug chambers and fast-twist barrels. Trigger pull adjusts from 3 to 6½ pounds.

But what kept my eyes from glazing was the barrel stamp: 257 Bartz. Huh?

All these loads functioned properly through the Brenton rifle and delivered fine accuracy. I could have nudged all a bit faster, as there was nary a hint of cork-popping pressure. Still, the Hornadys registered 2,945 fps. How fast must a bullet go to kill a deer?

Perhaps a Brenton AR will someday earn classic status among deer and sheep rifles. On the other hand, my Winchester High Wall in .25 Krag and Remington 700 in .25 Souper have yet to wear out their welcome!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)