Cartridge Board

22 Long Rifle – The Middle Years

column By: Gil Sengel | October, 25

An obvious solution was to design a somewhat larger-caliber rimfire cartridge. It could use a longer, heavier bullet that was less affected by the black-powder fouling and more accurate at longer range than the 22 LR. Given the problems with the 22 Extra Long (covered in the last column), Stevens attempted this in the 1890s with the introduction of the 25 Stevens rimfire. The original load used a 67-grain inside-lubed bullet and 11 grains of black powder. Target shooters weren’t interested. In 1902, Stevens offered the 25 Stevens Short with a 65-grain, inside-lubed bullet ahead of 4.5 grains of black powder to compete with the 22 Short in gallery shooting. Target folks adopted neither .25 caliber, but it did gain some popularity with small-game hunters.

The “secret” to making Vieilles powder didn’t remain secret very long. Alfred Nobel developed a similar compound within two years. So did the British, but they formed it into long strips and called it “Cordite.” In July 1895, the King Powder Company of Cincinnati, Ohio, began building a production line for smokeless powder. Black powder was obsolete, but not right away, for 22 rimfires.

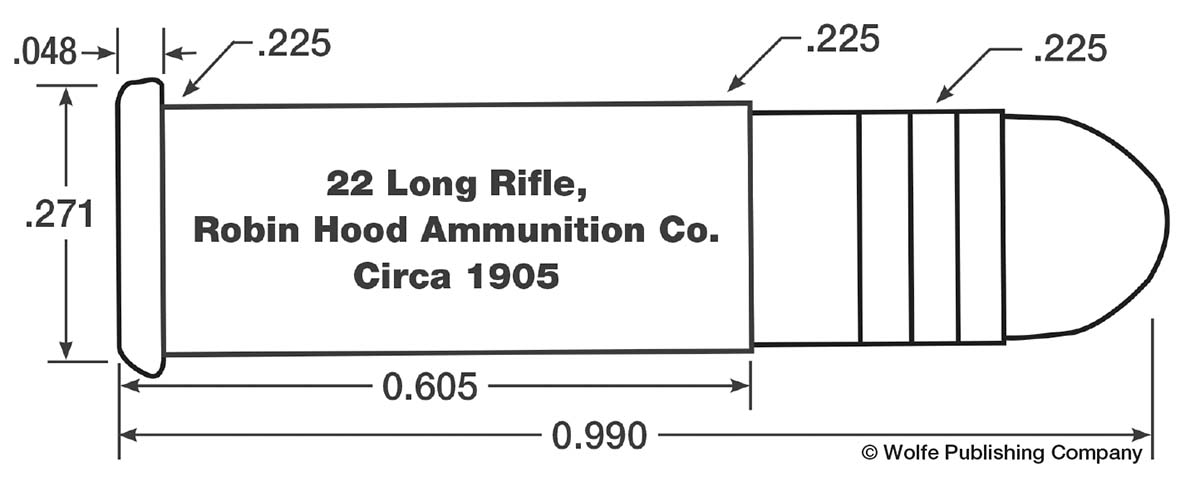

King Powder Company had a smokeless powder available in about a year. Peters Cartridge Company (owned by King) loaded it. By the turn of the century, DuPont and several others were making smokeless compounds called “powders,” though some appear to have performed more like explosives than propellants. Diving into the weeds regarding smokeless powders for 22 rimfires is not the interest here. Suffice to say, Winchester began loading 22 Shorts and Longs listed as smokeless in 1896, BB Caps appeared in 1901, but no 22 LRs. This didn’t happen until 1905. Muzzle velocity was listed in various places as 1,050 to 1,100 fps.

The reason for this late date was the smokeless powder available at the time – all smokeless powders. They produced higher pressure, often twice that of black powder. Thus began the development of a brass case to replace the weaker copper variety. Burning temperature was also higher, making the new powder “erosive” (the word used at the time). And what was eroded? Steel, of course, barrel steel. The chamber throats became rough, then the lands directly in front of the throat began to disappear. This affected accuracy.

Word traveled slowly at this point in history, but fortunately, the salvation of all 22 rimfires was already in existence. This was Kings Semi-Smokeless Powder produced by the previously mentioned King Powder Company. Inventor was Milton F. Lindsley. Also, despite differences of opinion, the powder was a mechanical mixture of black powder and smokeless powder according to its patent application. There does not, however, seem to be any record of the proportion of black powder to smokeless or what the smokeless was. King Semi-Smokeless was sold to individuals by grain size (similar to black powder) and was said to produce pressures no higher than black powder, while not being erosive. Thus, it was safe to use in old iron-frame guns and muzzleloaders. The introduction was in 1896.

The end of World War I saw the U.S. Army wanting a 5-shot, bolt-action training and match rifle. In August of 1919, at Camp Caldwell, New Jersey, during the National Rifle Matches, Winchester showed prototypes of what would become the famous Model 52. Savage also had a rifle, later called the M1919. The Savage failed in several respects, but the Winchester went on for sixty years as America’s premier 22 rimfire match rifle. This was the beginning of the end of the fine single-shot 22 LR target gun.

New smokeless powders gradually became less erosive, and attention was turned to primers. In the 1920s, all priming compounds contained mercury and potassium chlorate. When the cartridge was fired, some of the mercury was driven into the brass case, making it brittle and unsafe for handloading. The potassium chlorate (a salt) caused bore rusting if not removed in a few hours.

There is one other topic concerning the middle years. This is muzzle velocity. While black powder gave the 40-grain bullet about 970 fps, early smokeless and semi-smokeless powders raised this to 1,050 fps. I could find only one reference to groups produced by black powder 22 LRs and that was about .75-inch groups at 25 yards. The later erosive smokeless and King Semi-Smokeless were more thoroughly tested. Groups of .70 inch at 25 yards, 1.75 inch at 50 yards and 3.55 inches at 100 yards were considered good, though this varied some between ammunition brands, lots and rifles.

By 1930, velocity had been raised to 1,300 – 1,400 fps from cartridges designated as Remington “Hi Speed,” Federal “XL,” Winchester “Super Speed” and Western “Super.” Cases were brass only. At first, they were less accurate than the 1,050 fps smokeless loads, but this improved. Many reported 2.5- to 4.0-inch groups at 50 yards. This is from otherwise accurate rifles. Some produced 1.5-inch, 50-yard groups. Eventually, the very best rifles firing the very best lots of the very best ammunition would average 1.75 inches at 100 yards according to Whelen. Keep in mind that while small-game hunters liked the flatter trajectory, group sizes still prevented most 100-yard shots.

World War II interrupted everything. Its end would bring more changes to the old 22 LR, which will be covered next time.