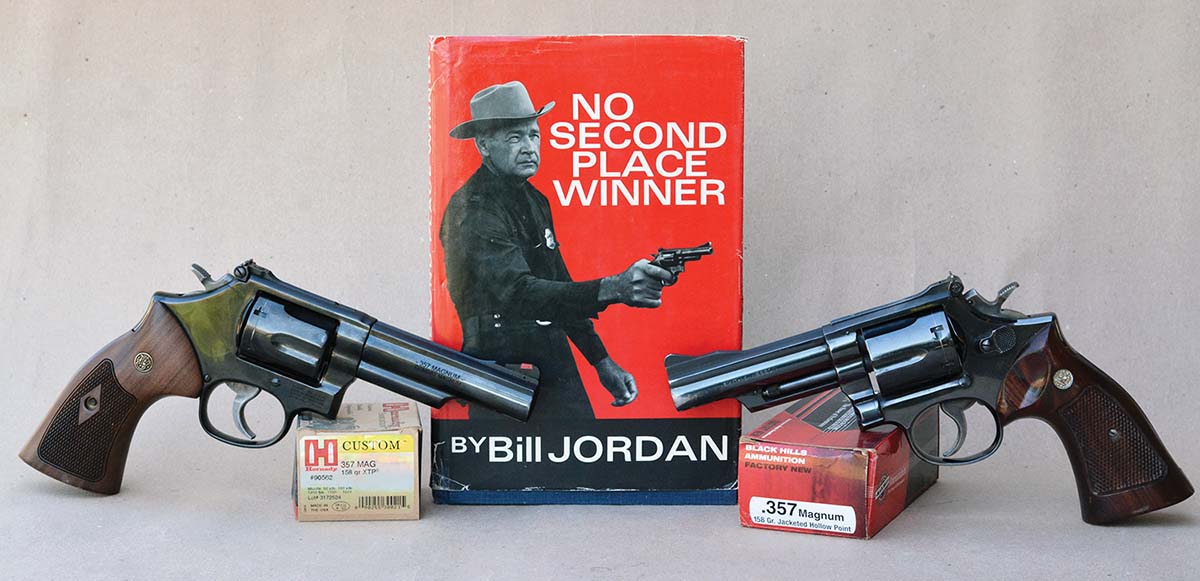

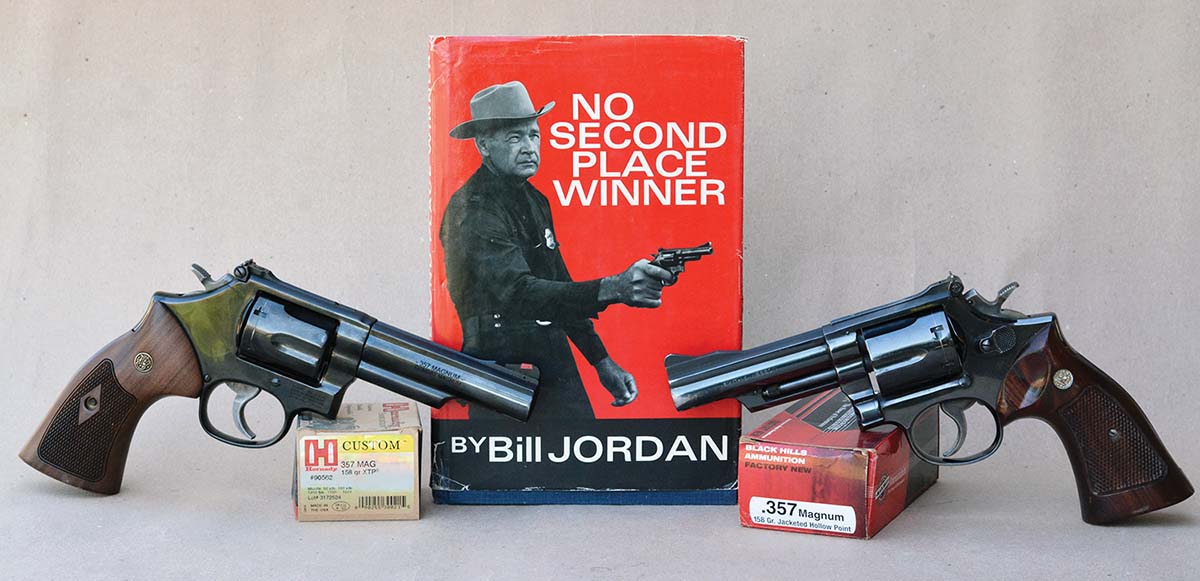

The Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum was introduced in 1955 and became the Model 19 in 1957. It was the brainchild of famous lawman, combat veteran and gun writer Bill Jordan. A current Model 19-10 (left), and a Model 19 (right) are shown.

The Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum, chambered in 357 Magnum, was introduced in 1955 and later became the Model 19 in 1957. For several reasons, the new sixgun was destined for widespread popularity and remained in continuous production through 1999. It was also offered in stainless steel beginning in 1970, which became the Model 66, but that model was discontinued in 2005. After a decade of absence and great demand, the K-frame Combat Magnum Model 66-8 was reintroduced in 2014, but with some notable engineering changes. With a returning interest in traditional blue-finished sixguns, the Model 19-10 has also been reintroduced.

The Combat Magnum was the brainchild of the legendary Bill Jordan (1911-1997), who is probably unknown (but should be known) to many younger generations. In short, Bill served as a U.S. Marine during World War II and the Korean War and served 28 years as a Border Patrol Agent. I knew Bill well, and, in typical Southern gentleman tradition, he rarely discussed many things that had to be done in the line of duty in combat and law enforcement. He was the real thing and shared with me some of his experiences and stories that will probably never be told.

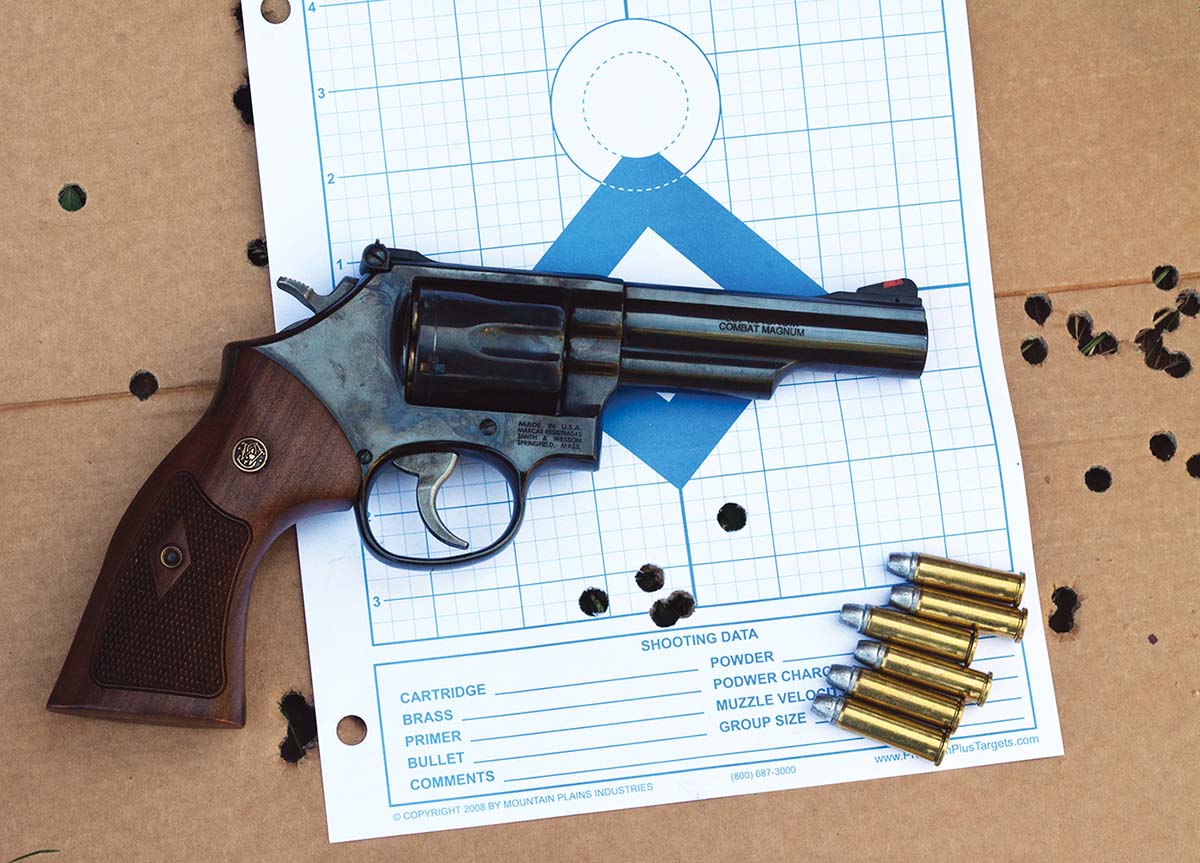

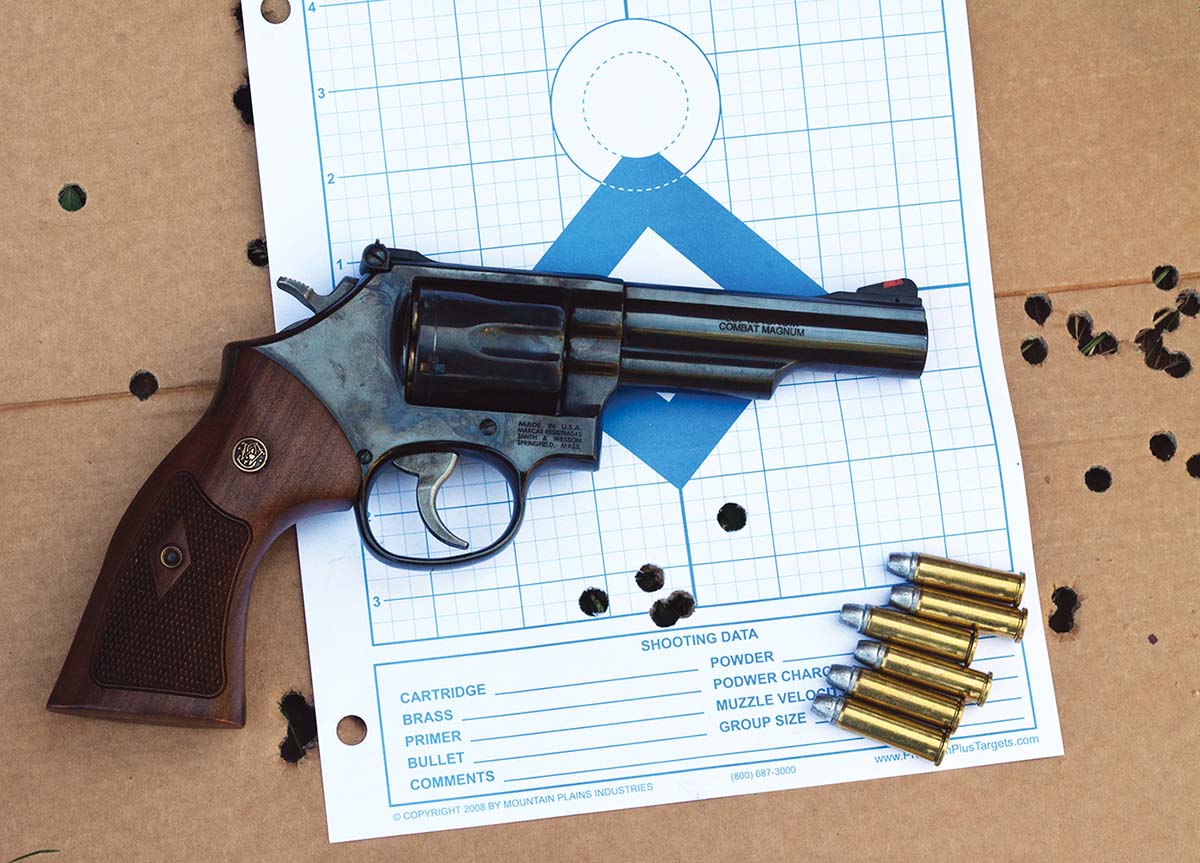

Brian developed handloads for the Smith & Wesson Model 19-10 that gave respectable accuracy.

Jordan was known for his incredible speed with sixguns and even appeared on several national television shows to demonstrate his skill, which included both accuracy and speed. He was able to draw, fire and hit his target in .27 of a second using a Smith & Wesson sixgun. I first met Jordan in 1983, when he traveled to Idaho to help John Taffin establish the Elmer Keith Museum Foundation. In the subsequent 14 years, I had the opportunity to hunt with him and spend considerable time with him at many industry events.

The Model 19-10 (left) features a two-piece barrel, while the original Combat Magnum and Model 19 (right) featured a traditional one-piece barrel.

Jordan carried a sixgun daily for many decades and loved the size and weight of the S&W K-38 Combat Masterpiece (later becoming the Model 15) with a 4-inch barrel; however, he also knew that the 38 Special could be on the weak side in gunfights and when trying to shoot into or through a vehicle. Jordan wanted 357 Magnum performance, but considered the N-frame heavier than needed for daily belt carry. He met with Smith & Wesson President Carl Hellstrom and requested that he offer a K-frame chambered in 357 Magnum, but with a shrouded barrel, fully adjustable Micrometer rear sight, ramp-front sight, and 4-inch straight, non-tapered barrel. All of that is much easier said than done, as the standard pressure 38 Special is generating 17,000 pounds per square inch (psi), while the 357 Magnum at that time was well over 40,000 CUP (but today is 35,000 psi). That is too much pressure and power from a standard K-frame that was originally developed for the 38 Special in the 1890s.

The front sight is ramped and features a red insert.

Hellstrom knew the sixgun that Jordan outlined would have merit and put his engineers to work. They employed higher-strength steels, but also increased the frame depth in front of the cylinder and other details that served to increase strength. While the standard 38 Special cylinder was long enough to accommodate a standard 357 Magnum cartridge (naturally with the chamber cut longer), the cylinder was increased in length, which shortened the unsupported barrel (barrel proper) that extends back through the frame. This was important, as the barrels of K-frame revolvers are relatively thin in this area, and it was necessary to handle the higher-pressure magnum cartridge. Chambers were counter-bored (or recessed).

The rear sight is Smith & Wesson’s famous Micro – fully adjustable for windage and elevation.

Both Hellstrom and Jordan knew that the new Combat Magnum would not have the strength or durability of the larger N-frame 357 Magnums, such as the Models 27 and 28 (with both of those models evolving from the famous 357 Registered Magnum). The concept was that the Combat Magnum would be fired primarily with 38 Special ammunition for target work, practice by police, etc., but full-power 357s would only be used when the extra power was needed and would be used sparingly.

Unfortunately, the Combat Magnums were fired with magnum cartridges much more than they were intended, which tended to loosen them up. There was another bigger problem; the thin barrel proper tended to split, requiring a new barrel. This was a combination of either firing too many full-house magnum rounds, especially loads containing high-velocity 125-grain bullets, or firing lead bullet ammunition (such as pure lead wadcutters) that tended to build up lead fouling in the forcing cone, and then firing a jacketed 357 Magnum load without first cleaning the lead out of the forcing cone.

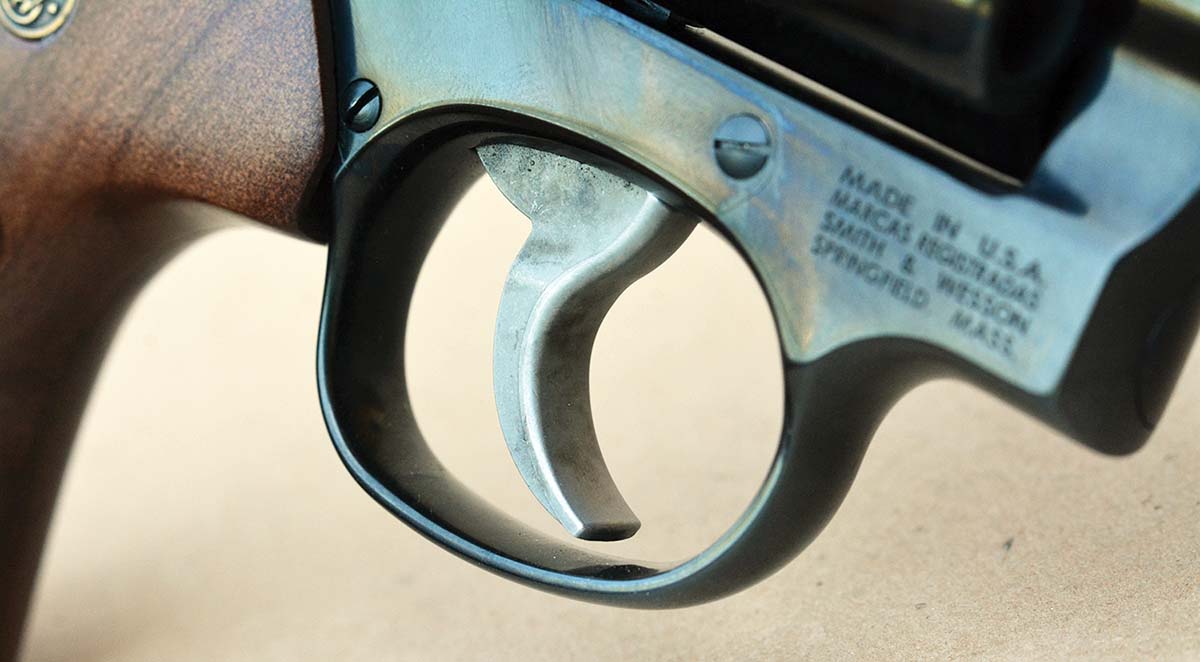

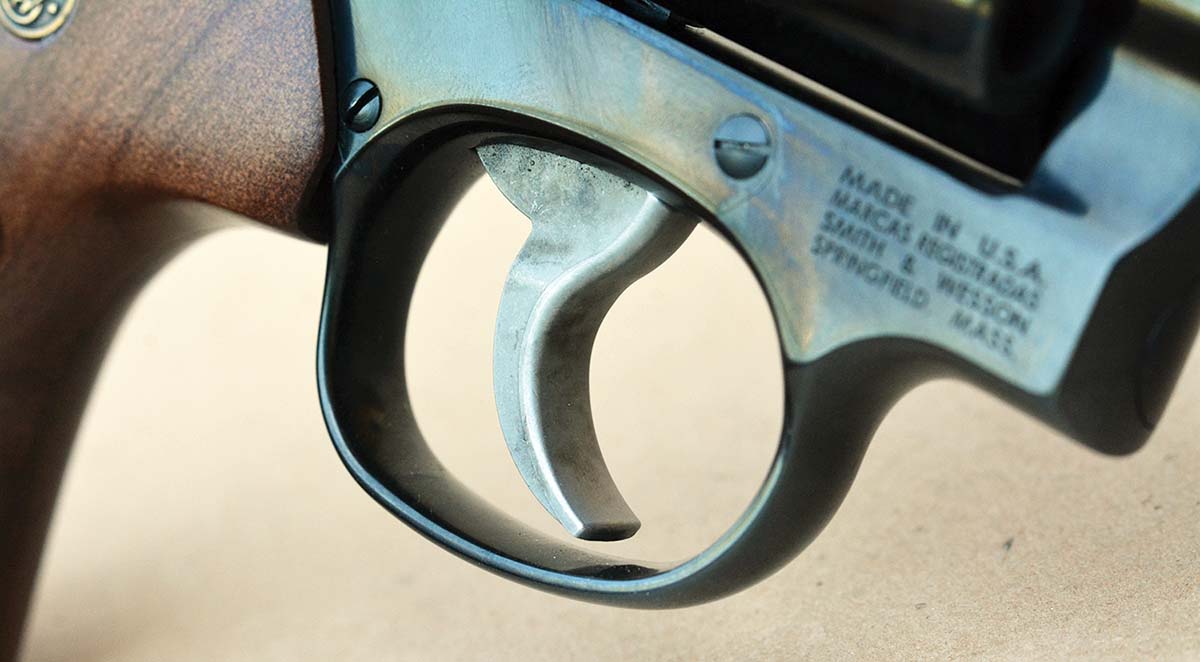

The MIM trigger is smooth and features a flat face.

I have never split the barrel of a Model 19 or 66, even after firing thousands of rounds through a brace of guns; however, I have primarily used cast bullets and rarely use maximum loads. My handloads still offer near full-house magnum performance, but pressures are generally held to around 30,000 psi. I have replaced the barrels on two guns for others and have seen several additional guns that were split. This was the primary reason that Smith & Wesson developed the larger L-frame Models 586 and 686 in 1980 as the Distinguished Combat Magnum.

Shortly after the Combat Magnums were discontinued, a Smith & Wesson engineer told me that if these guns are fired with a steady diet of 357 Magnum jacketed loads, they will all eventually split the barrel – the primary reason it was discontinued in 1999 and 2005, respectively.

The latest Model 19-10 has some notable engineering changes that eliminate the above problems. There is not enough space to discuss all the details. However, probably most important is that the cylinder now locks at the crane and the breech of the cylinder, no longer locking at the ejector rod end. The ejector is still shrouded to protect it if the gun is subjected to harsh use or dropped. The crane lock substantially increases durability when fired with full-house magnum loads. To address the barrel proper splitting problem, the receiver threads are larger, resulting in a barrel proper with approximately a .020-inch larger diameter. Furthermore, the cylinder has been lengthened approximately .040 inch (when compared to a 1994-era Model 19-7 gun), which results in less barrel proper protrusion into the frame window. These two changes add significant strength to the barrel breech or proper and should eliminate the possibility of barrels splitting.

To increase durability, the Model 19-10 features a new lock inside the crane.

This new sixgun features a fully-adjustable micro-rear sight, ramped front sight (with red insert), walnut target stocks, standard width smooth trigger, standard hammer, frame mounted firing pin, round butt grip frame and a slightly beveled cylinder front. The finish is very dark blue, but it offers a reasonable polish. It is noteworthy that the key lock hole is gone (thankfully)! The cylinder locks tight and has very minimal endshake. The barrel cylinder gap measures .009 inch, which is within the industry maximum of .012 inch, but I would like to see it around .004 to .005 inch on double-action sixguns.

For the first time in the Model 19 history, the ejector rod does not lock in the barrel shroud.

Around 2000, Smith & Wesson began employing Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) rifled barrels. Generally speaking, but not always, these produced lower velocities, gave up accuracy and were not as well suited to cast bullet loads. Smith & Wesson has abandoned that rifling and returned to their proven rifling pattern. It should be noted that this new barrel is a two-piece barrel, which is supposed to assist production with holding tighter tolerances and keep costs down. Frankly, for several reasons, I don’t buy that and would like to see them return to their traditional one-piece barrel. The outside diameter of the barrel is .770 inch at the muzzle, while a 1970 vintage Model 19-3 measures .680 inch. While that is not a huge difference, the new barrel looks notably heavier, but the weight of the gun is still 37 ounces, just like the originals.

Smith & Wesson has been using Metal Injection Molding (MIM) hammers and triggers (and other parts) for a couple of decades, which were prone to problems early on; however, they have been improved substantially. Time will tell just how durable they actually are. As indicated, the trigger is smooth, but rather flat on the front, which should be changed to a rounded profile for ideal double-action work.

The Model 19-10 provided respectable accuracy with cast bullet loads.

The action is a bit stiffer than I would like to see; however, a good action job will do wonders in smoothing up the single-action and double-action pulls. The SA pull broke clean at an excessive 5¾-pounds, which is almost twice as heavy as it should be and actually made precision shooting more difficult.

As can be seen in Table II, four factory loads from Black Hills Ammunition, Hornady and Remington gave respectable accuracy. Each load was fired with five-shot groups at 25 yards with the help of a sandbag rest. Each load was fired for three groups and then averaged. Combining the accuracy of all loads came to 2.26 inches, which is good! The most accurate factory load was the Black Hills 158-grain JHP that produced 1,233 feet per second (fps) and averaged 1.75 inches.

The barrel proper has been shortened and increased in diameter to prevent barrel splitting.

Moving on to six handloads that contained both jacketed and cast bullets, the average accuracy came to 1.80 inches. The most accurate load consisted of the old proven Lyman Thompson cast bullet with gas check from mould 358156, which cast at 162-grains and sized to .358 inch. Starting with new

Starline cases that were full-length sized, then primed with a CCI 500 standard primer, 9.0 grains of Accurate No. 5 powder reached 1,265 fps and grouped into 1.40 inches.

Obviously, today’s review has been mostly positive, but has also pointed out some areas that need improvement. The Model 19-10 lacks the slick out-of-the-box double-action and light single-action pulls and bright blue finish of its predecessors. Regardless, it is a good gun that is accurate, reliable and far more durable than previous Model 19s. It is great to have the Smith & Wesson Combat Magnum back!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)