Old Faithful

The 32-40 Never Ages

feature By: Terry Wieland |

Intended initially by Ballard and Marlin for target shooting, it was soon being used in lever-action hunting rifles as well. I know of at least one English double rifle in 32-40. I have heard of, but never seen, a break-action single-shot pistol, and it would not surprise me if somewhere along the line, some bright light built a revolver for it.

What does this say about the 32-40? Not only is it highly accurate, it’s also remarkably versatile within its limits, and admirably docile. Those characteristics will keep a cartridge around long after it’s been superseded ballistically by the latest hotshot. It is also a lot of fun to shoot, and can be loaded down to about 32-20 performance, or jacked up to (almost) 30-30. The cartridge’s sweet spot, however, is with a 165- to 185-grain cast bullet at around 1,500 feet per second (fps).

The 32-40 was introduced by Marlin in 1884 as a target chambering for the single-shot Ballard, which Marlin owned. It became very popular very quickly, so much so that Winchester began chambering its rifles for it and even called it the “32-40 Winchester,” the name by which it’s commonly known. It is also referred to as the 32-40 Marlin and 32-40 Ballard, but all are the same cartridge.

With such a long and checkered history, it’s no wonder the 32-40 has been loaded in every configuration known to cartridges. It has used both black powder and smokeless, as well as duplex loads combining a pinch of smokeless with a case full of black, and a pinch of black behind a charge of smokeless.

If one wished to be absolutely exhaustive, one could write an entire book (or at least a lengthy pamphlet) on reloading the 32-40. Previous efforts have concentrated on hunting loads more than target, and attempting to get something resembling 30-30 performance. One such, a “Pet Loads” article by Ken Waters in 1972, made the point that 32-40 rifles should be divided into those with strong actions and those with weaker ones.

In the latter case, the most obvious and the most likely to be found are Ballards and Stevens No. 44s. In both cases, we need to pay close attention to pressures. Since the best target accuracy seems to be found well below anything approaching maximum, there is a lot of wiggle room.

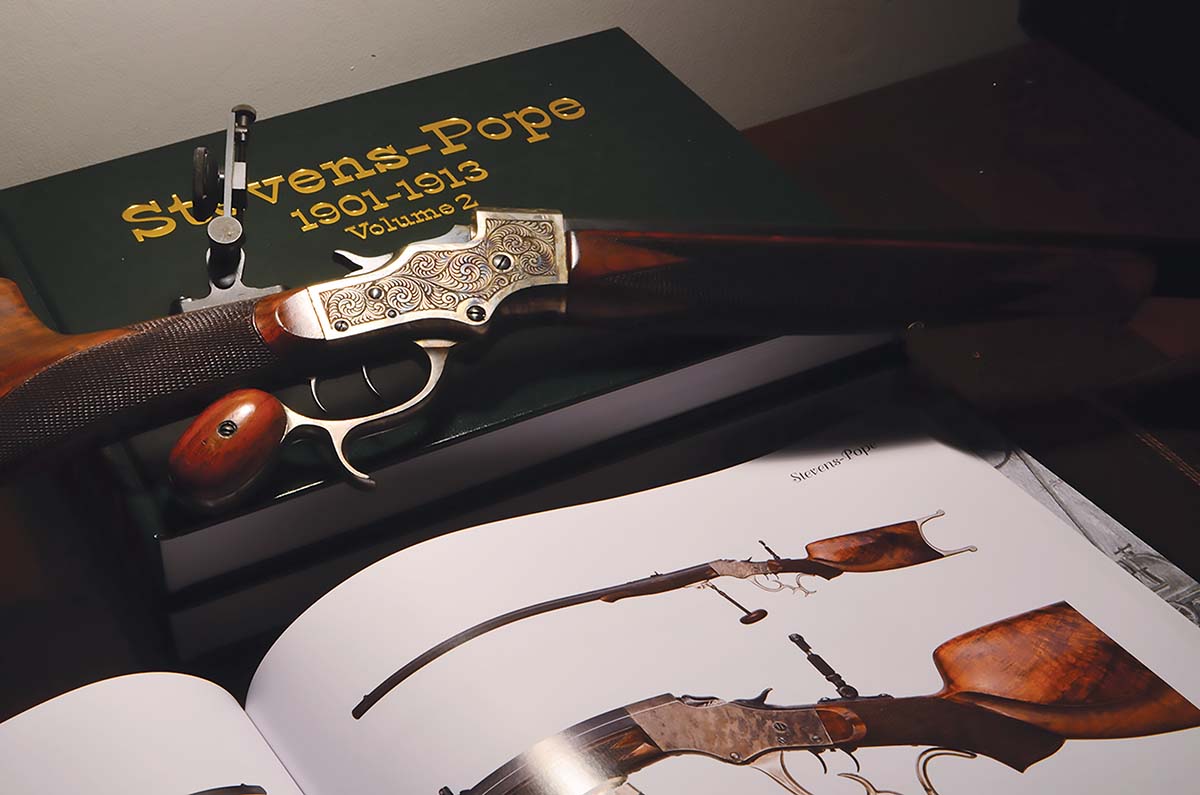

But the 32-40 certainly made its mark: In 1901, C.W. Rowland of Boulder, Colorado, fired one of the most famous accuracy groups in history: 10 shots, 200 yards, .721 inches. Fifty years later, this benchrest record still stood. The rifle, known as the Rowland-Pope, was custom-built by Harry Pope using one of his barrels on a Ballard action. The cartridge was 32-40, and it had a very long, very heavy barrel with a false muzzle. No one knows exactly what Rowland’s load was, but many people wish they did.

It’s difficult to pin down actual SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) pressure standards for the 32-40, partly because some are given (such as they are) in pounds per square inch (psi) while pressure data for loads from years ago, where they are given at all, are usually copper units of pressure (CUP).

We should note that around 1910-1920, Winchester came out with some high-pressure factory hunting ammunition, followed shortly by Remington with some that was even hotter. Apparently, the boxes carried the usual warnings that few buyers ever paid any attention to, and it was withdrawn pretty quickly. No casualty figures are available, but I’d bet there were a few.

The Remington ammunition listed pressure at 36,000 psi, well above what Waters considered maximum for strong actions (30,000 psi). A SAAMI chart shows a maximum of 30,000 CUP, for which no correlation can be drawn. For weaker actions, Waters set a maximum of 20,000 psi, which seems reasonable.

The latest Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook, 4th Edition, lists loads ranging from 8,500 CUP (Pyrodex) to 29,000 with IMR-4198. This suggests the book follows SAAMI restrictions without differentiating among the various actions; since the starting loads for 165-, 170- and 200-grain cast bullets are in the 14,000-18,000 CUP range, delivering velocities of 1,400-1,600 fps, I would be comfortable with any of these to start with.

Bullets are all over the map, as are bore diameters, but let’s start with the 165-grain bullet that was the 32-40 standard from the beginning. These can be anything from .319 to .321 inches. Typically, if Harry Pope barreled a Stevens 44 for you in 32-40, he would build it with a false muzzle and bullet starter, make you the appropriate bullet mould and, probably, tell you what lead alloy to use, and even the best lubricant.

It was acknowledged that the way to get the best accuracy was to seat the bullet from the muzzle, thereby engraving the rifling and eliminating “drag fins.” If you were using black powder, the bullet did not need to be a tight fit, since soft lead would be “bumped” by the detonation. A cartridge case containing the powder was then chambered behind the bullet.

Another approach was to use a bullet seater to push the lead projectile up into the rifling, and chamber the case behind it; yet a third way was to partly seat the bullet in a not-too-tight case neck, then allow it to be seated deeper by the rifling as the action was closed and the round was chambered. This, of course, required a special neck sizer.

With smokeless powder, which never filled the case, some shooters raised the muzzle straight up before firing to ensure the powder was back against the primer; others lowered the muzzle to push the powder up against the base of the bullet. Everyone who ever squeezed a trigger, it seemed, had his (or her) own theories about what worked best, and the winners, all too often, kept it to themselves. When you start breaking it down, the possibilities are endless.

Fortunately for us all, one can usually find some suitable cast bullets for not much money. As you progress, you may well find yourself casting your own, which takes us into a whole new realm of possibilities and permutations. For now, we’ll stick to commercial cast bullets and smokeless powder to simply get the old girl shooting again.

My first 32-40 was a Savage Model 1899, made on special order around 1916 with a 26-inch barrel. It was, I believe, made to be a Schützen rifle, and a lovely and accurate thing it is. The Savage action makes it easy to seat a bullet deeper into the case and touch the rifling as you close it. My early loads with that rifle would keep ten rounds in a four-inch square at 200 yards with a receiver sight, and one can’t ask much better than that. At least, not from me.

To open the case neck slightly to allow chamber-seating, I got an RCBS Cowboy Action 32 Special die with a .322-inch sizer plug. Of course, you need to bell the mouth slightly before seating the bullet, then iron it flat without crimping or applying excess pressure. This is one of the many trial-and-error processes involved in loading ammunition for these old beasts. I’d say it’s part of the charm, but in reality, it can drive you to drink.

With proper brass in place, primed and sized appropriately, and a supply of bullets to work with, we come to powders.

The Lyman Reloading Handbook, 45th Edition (1970) listed Unique, 2400 and IMR-4227; at the moment, only IMR-4227 is available. The newer Lyman 51st Edition Reloading Handbook (2021) gives many more options, although curiously, none of the above. Some are no longer available (SR-4759), while others are out of stock (RL-7, A-5744, Trail Boss); however, you can still obtain both IMR-4198 and IMR-3031. The Hodgdon website lists four powders: H-4227 is discontinued, and Trail Boss is out of stock, but they still have both H-110 and Lil’Gun. Curiously enough, they list pressure-tested loads only for heavy bullets 196, 202 and 204 grains.

If I had to name my favorite powders for target loads in my venerable Stevens, they would be, in order, SR-4759, Unique, Accurate 5744 and IMR-4227. Keep in mind, these are for light target loads with cast bullets. IMR-3031, while a great powder, just doesn’t fit the profile; great for jacketed bullets at higher velocities in a lever action, but not for our purposes here.

Ken Waters considered IMR-4198 one of the best performers for light target loads with cast bullets, but it’s one of those where you have to pay attention to the position of the powder in the case before pulling the trigger.

The accompanying table gives some examples of what to expect, ballistically, with light loads for old rifles. Each of these loads is a pussycat in terms of noise and recoil. Unique, as always, is reliable, and that load could be pushed to the classic “8 grains of Unique” if you want a little more velocity. Otherwise, IMR-4227 would be my first choice if I were working up a serious load to compete with C.W. Rowland.

In terms of bullets, I would search out more of those Loverin-designed 186-grain, from Lyman mould 319201. As you can see, the velocity is spot on and the extreme spread is low, meaning it’s consistent.

Frankly, though, I would be happy heading for the range with any one of the loads on that chart. The wonderful old 32-40 is nothing if not docile and cooperative.

.jpg)