Tubular Bullets

Game Changer or Gimmick?

feature By: Art Merrill | October, 25

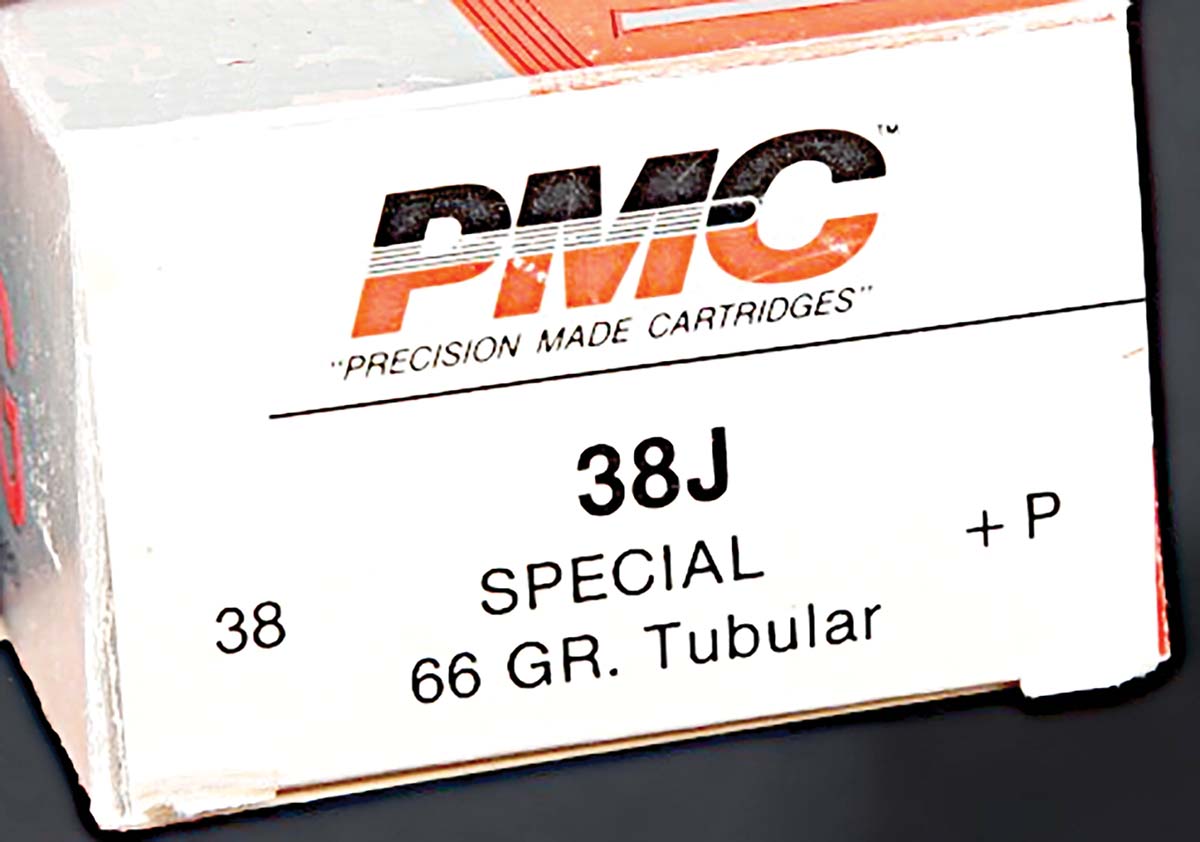

There is much speculation, rumor and misinformation surrounding the tubular bullet, especially the reason manufacturer Precision Made Cartridges (PMC) discontinued its line of Ultramag ammunition after only a very short run in the late 1980s. Did ATF ban them as armor-piercing? Did they punch “cookie-cutter” holes in soft targets? Are they illegal to possess? Can handloaders make their own version? An acquaintance recently gave me a handful of PMCs – long-gone, 66-grain 38 Special +P Ultramag tubular bullet ammunition, calling them “cookie cutters” and claiming samples shot into Kevlar draped over a mannequin punched neat, round holes through both. The claim and the unusual bullet configuration prompted this investigation.

The successful tubular bullet design is technically a ring airfoil. It behaves in flight rather like a wing, which, of course, is also an airfoil. A ring airfoil is a hollow cylinder that, in cross section, somewhat mimics the taper of an aircraft wing. You can easily demonstrate the principle yourself by simulating the ring airfoil with a properly folded and rolled sheet of common copier paper and a bit of tape. After dredging through forgotten corners of memory, I recently spent a half-hour of side-tracked amusement constructing a working model and sending the paper ring airfoil flying about my living room and careening into the wife’s house plants.

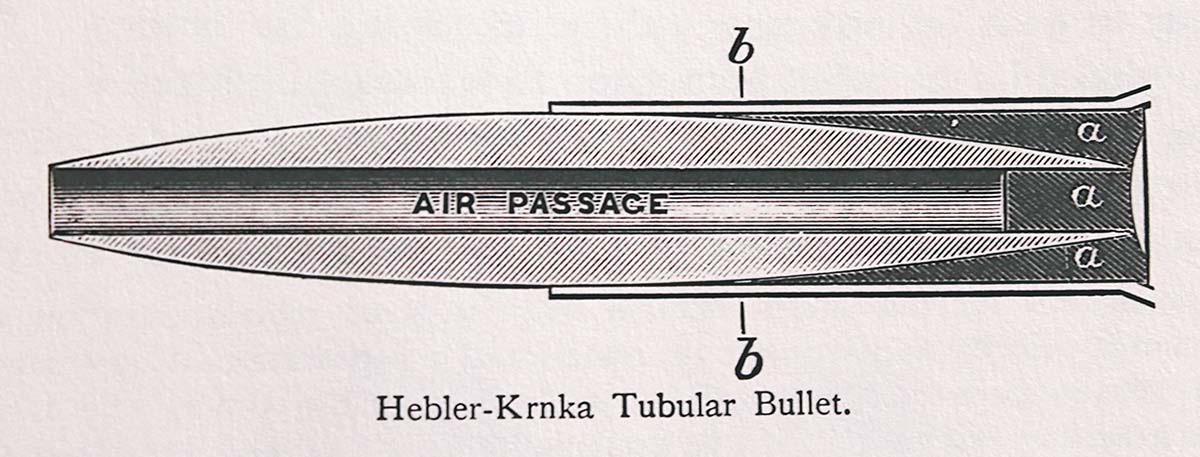

Another way of perceiving the tubular bullet is as an ordinary bullet with a hole drilled all the way through. Such a bullet is not a new concept, having origins dating back to 1857 in a “Whitworth” bullet, which may be attributed to English engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth, inventor of the Whitworth rifle. In August of 1893, the United Service Gazette reported in detail on further experiments resulting in the Hebler-Krnka tubular bullet. The Czech gunsmith/inventor and Swiss Professor duo determined that their best tubular bullet design displayed an amazing .0089 percent of the drag exhibited by the most modern, high-tech bullets of the day – the 8x57J bullet fired from the Mauser 1888 Commission Rifle.

Ring airfoil bullets achieve incredibly low drag numbers because, at supersonic speeds, they don’t develop the large “bow shock” wave inherent to solid bullets. They also exhibit far less of the turbulent air flow off the back end of the bullet that contributes to bullet drag. But the perception of the tubular bullet as simply a bullet with a hole drilled through it is grossly inadequate, akin to describing a modern nuclear aircraft carrier as “a boat.” Physicists and engineers, more recently experimenting with increasing the performance of ring airfoil/tubular bullets, discovered that the resulting device actually combines the elements of both an airfoil and the inlet of an aircraft jet engine, neither of which existed during the Hebler-Krnka experiments.

Fast-forwarding to the 1970s, the ring airfoil/tubular bullet concept evolved into the Ring Air Foil Project (RAFP) or Ring Airfoil Grenade (RAG) project to garner greater range from the U.S. Army’s 40mm grenade. Engineers Abraham Flatau and Joseph Huerta, working for the U.S. Army, designed a launchable grenade on the ring airfoil principle. The Army certainly had other reasons to abandon the project, but probably foremost among them is that an efficient ring airfoil grenade is extremely limited in the payload it can carry. Manipulating physics is always a game of trade-offs, and an efficient ring airfoil grenade carrying an adequate charge of explosive and shrapnel would have to be significantly larger and heavier (and require a much larger propellant charge) than the Army’s 40mm grenade, negating any hoped-for advantage in achieving more distance. Nonetheless, the U.S. Patent Office issued a 1979 patent to Flatau, Huerta and the U.S. Army on the RAFP concept, and Flatau left Army employ to develop a successful ring air foil bullet for the commercial market.

A patent search for this investigation found that Flatau has at least 20 patents with his name (and Huerta, five), almost all for projectiles, including for ring airfoil tubular bullets. Flatau’s bullet, made of alloy enclosing a steel ring, was capable of penetrating soft Kevlar body armor, such as that which police wear. Guilford Engineering Associates (GEA) apparently manufactured 45 ACP, 9mm Luger, 38 Special and 357 Magnum experimental and commercial ammunition featuring Flatau’s armor piercing bullet for several years before President Reagan in 1986 signed legislation banning commercial alloy handgun bullets that can penetrate body armor. Flatau returned to Army employment to further develop his RAFP bullet, the effectiveness of which he demonstrated by shooting it through a hard Army Kevlar helmet worn by, the story has it, a hapless goat.

Still, the Army declined to pursue the concept for deployment. Part of the Army’s reasons this time again appear to be due to the ring air foil bullet’s necessarily light weight, which causes the bullet to impact targets well below the point where traditional bullets impact, even though velocity is quite high, necessitating sight changes. Another reason is perhaps because the unique bullets have some reputation for losing accuracy over distance, compared to traditional bullets.

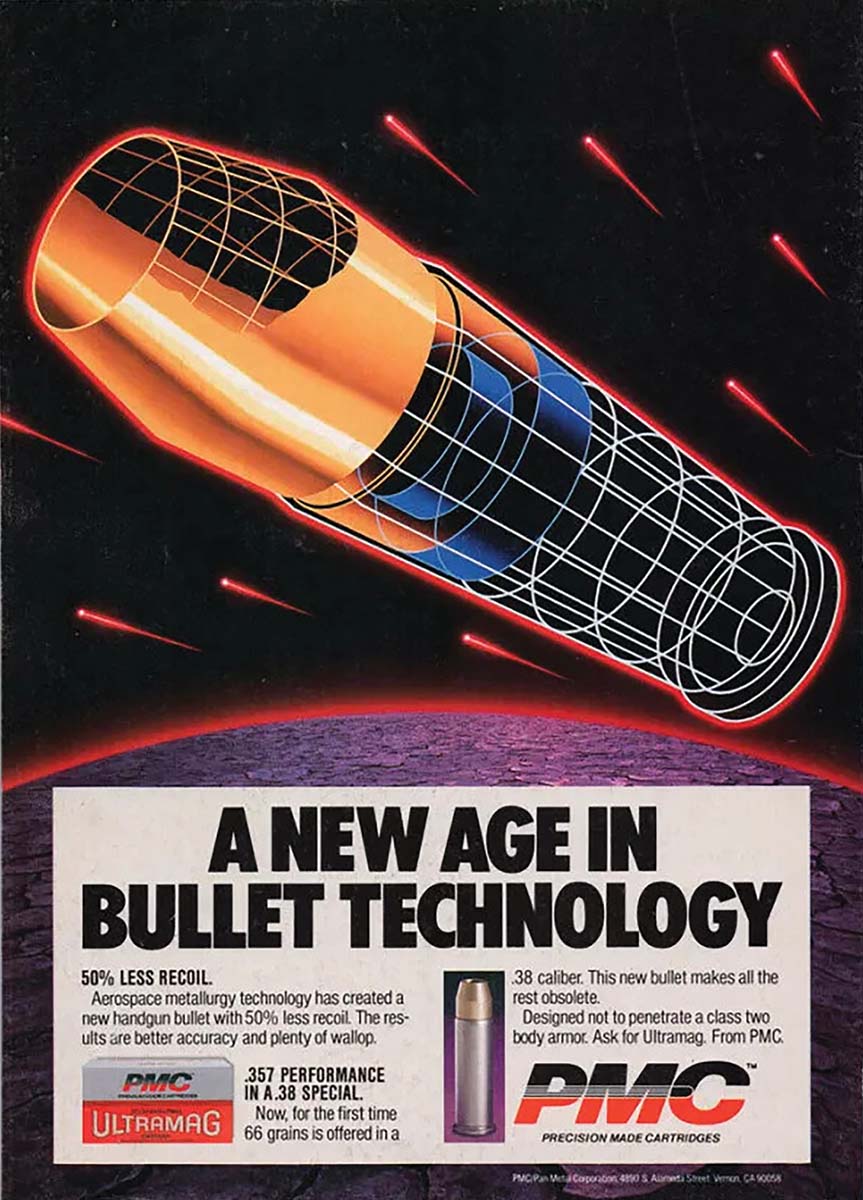

In the mid to late 1980s, ammunition manufacturer PMC picked up where the Army and GEA left off, but the ring airfoil bullet was destined to be quickly orphaned once again when PMC dropped the cartridges, which they had labeled “Ultramag,” after only a few years. More on that below.

In breaking down a PMC Ultramag 38 Special +P tubular bullet cartridge, I found that PMC had crimped the bullet so incredibly tightly into cases that a kinetic bullet puller couldn’t budge it one iota; in fear of breaking the kinetic puller, I switched to a collet-style puller. Even then, it was necessary to give the collet handle a few raps with a dead blow mallet to force the collet to grip the bullet tightly enough, and then to use both hands to raise the press handle to extract the bullet. Once accomplished, I discovered a dried black substance between the bullet and the case wall, probably a sealant but perhaps an adhesive, which may have contributed to the bullet’s recalcitrance.

Ultramag’s case, powder and primer are all conventional with only the projectile differing from traditional ammunition. Having no solid base, the ring airfoil bullet needs something for propellant gases to push against rather than simply escaping through the bullet’s central cavity. Other experimenters have utilized a sabot; Flatau used what he called a “pusher disc and obturator.” PMC’s “pusher disc” is a thick, synthetic block between bullet and powder charge. Like a sabot, the disc falls away upon exiting the muzzle so that the bullet can do its ring airfoil thing as it flies downrange. It was nearly as stubborn as the bullet to coax from the case; I had to expand the case mouth and give it a squirt of penetrating oil before the kinetic puller could extract the disc.

In a silhouette profile, the bullet nose shape might be called a truncated cone. The nose is so shaped to promulgate supersonic airflow through the center of the bullet, again, acting rather like a jet engine intake. The “intake” design is such that it essentially “swallows” the bow shock wave that a conventional bullet produces in flight, thereby significantly reducing or eliminating pressure drag (the drag caused by air molecules piling up in front of the bullet). Once the bullet slows below a certain Mach number (predetermined by the “intake”design), the bow shock wave then makes its appearance to create drag.

For the sake of accurate reporting here, I sacrificed several of my limited stash of PMC tubular bullets over a chronograph. From a four-inch-barreled Ruger Security Six 357 Magnum revolver, the 66-grain tubular bullets averaged 1,465 fps. At 15 yards, the ring airfoil bullets struck five inches below the point of impact of standard 38 Special 158-grain FMJ ammunition (at 830 feet per second) on a paper target, and showed about five inches of horizontal stringing.

Why did PMC abandon the Ultramag and its tubular bullet? Unfortunately, the company, owned by Poongsan Corporation in South Korea, did not respond to phone and email requests for information, so we are left with conjecture. There is some possibility that PMC soon terminated the manufacture of Ultramag ammunition over patent infringement issues. Instead of, or perhaps in addition to that, there simply wasn’t a self-defense market for the tubular bullet, despite its high velocity, because of its open-cylinder design, the ring airfoil bullet cannot expand upon impact, though it apparently does penetrate exceptionally deeply in soft tissue. I did not find definitive evidence from a reputable independent source that Ultramag’s tubular bullet does, indeed, punch caliber-size “cookie cutter” entrance and exit wounds through soft tissue but much less through Kevlar and mannequins. Its “cookie-cutter” sobriquet is perhaps due to the visual appearance of the yawning bullet nose cavity rather than to the terminal performance of the bullet.

Among the misinformation circulating around the PMC Ultramag tubular bullet is that it is armor-piercing and that it is illegal to possess. Regarding the first, a 1987 PMC advertisement for the ammunition specifically states that the bullet is “Designed not to penetrate a class two [sic] body armor.” According to the National Institute of Justice, Level II soft or hard body armor protects against 9mm, 40 S&W and 357 Magnum bullets/velocities. But PMC also made Ultramag in 44 Magnum, which may penetrate Level II armor (next-heavier Level III-A armor is supposedly impenetrable to 44 Magnum), so perhaps that is the source of the armor-piercing reputation.

Reading verbatim the Reagan-era ban on armor piercing ammunition - Public Law 99-408 which amends Chapter 44 of Title 18 United States Code that regulates manufacture, importation and sale of armor piercing ammunition. We find the definition of “armor piercing” as a handgun projectile made of “one or a combination of tungsten alloys, steel, iron, brass, bronze, beryllium copper or depleted uranium.” If the bullet of PMC Ultramag ring airfoil ammunition is made of copper, rather than beryllium copper alloy, it is excluded from the regulation. Also, note the regulation does not prohibit possession of its defined armor-piercing ammunition, only its manufacture, importation and sale.

Splitting hairs with ATF is a dicey undertaking for the ordinary citizen, and who hasn’t been flabbergasted by the illogical and irrational conclusions arrived at by government agencies and courts? The above is not legal advice, but it seems clear that there is nothing illegal in possessing or even using in self-defense – PMC’s Ultramag tubular bullet, whether made of copper or beryllium copper alloy. Though the Army’s 1979 patent (and Flatau’s 1986 patent) has expired with time, attempting to create and handload your own ring airfoil bullet ammunition may run afoul of that “manufacture” prohibition in the law.

In the end, PMC’s Ultramag tubular bullet cartridge is a collectible curiosity, a physics demonstration of the ring airfoil bullet concept that you can hold in your hands. Though it failed to outperform traditional bullets for practical applications, what handloader, cartridge collector, or aerodynamicist wouldn’t want an example of a bullet as a wing – or a jet aircraft engine intake? If you don’t like the collector price, you could still fold your own ring airfoil out of paper.