Wildcat Cartridges

6mm Swift (and Others)

column By: Layne Simpson | October, 25

The Lee Straight Pull rifle, developed by Winchester and adopted by the U.S. Navy in 1895, was chambered for the smokeless 6mm Lee cartridge loaded with a 112-grain bullet at a velocity of 2,560 feet per second (fps). A Sporting Rifle version with a nicely checkered walnut stock and a 24-inch barrel was introduced in 1897, but since fewer than 2,000 were sold, the American hunter obviously was not ready for a big-game rifle shooting such a small bullet. Winchester built the last Straight Pull rifles in 1916, and the availability of factory-loaded ammunition ended in 1935. If not for the later efforts of various wildcatters, the idea of using a 6mm cartridge for sporting purposes might have died then and there.

In his book Wildcat Cartridges, written during the 1940s, Richard Simmons includes information on dozens of cartridges in calibers ranging from the 17 Pee Wee to the 400 Niedner. Among them, the 240 Super Varminter may have been the first wildcat cartridge designed for use with .243-inch bullets. Formed by necking down the 270 Winchester case, it was developed by Jerry Gebby, who in 1930, had also created the 22 Varminter by necking down the 250 Savage case. Claimed velocities for the 240 Super Varminter were 3,733 fps for an 87-grain bullet and 4,008 fps for a bullet weighing 75 grains. Gebby copyrighted the Varminter name, and other gunsmiths avoided that obstacle by stamping 22-250 on the barrels of rifles built for their customers. I believe we can assume that gunsmiths also avoided the Gebby copyright on the 240 Super Varminter by necking down the 30-06 case (rather than the 270 Winchester case) and calling it the 6mm-06. The 6mm-06 was covered in this column in Handloader (No. 314, June 2018).

An article on the 240 Super Varminter written by F.C. Ness for the American Rifleman probably got the attention of shooters in another sport. Benchrest competition with modern rifles got its start in 1945 when several West Coast shooters formed a group called the Seattle Snipers Congress. A couple of years later, a group of varmint shooters led by Harvey Donaldson formed the Eastern Bench Rest Shooters’ Association. Many of the heavy-barrel rifles used were built around 1898 Mauser actions, although several other turn-bolt actions were popular as well. There was no limit on rifle weight. The 219 Donaldson on a modified 219 Zipper case quickly became quite popular, although rifles chambered for the 220 Swift, 22-250 and 220 Wilson Arrow won their shares of matches as well. The Arrow was formed by increasing the shoulder angle of the 220 Swift case to 30 degrees with no other change. It was developed by L.E. Wilson, who founded the company of the same name. The company still turns out his precision-made reloading dies and other tools. In the old days, benchrest rifles wore extremely long target scopes built by Lyman, Unertl and others, and due to their great length, the rear mount was attached to the receiver ring of the rifle while the other was out on the barrel. Magnification ranged as high as 24x.

While the 220 Swift and other cartridges of its caliber proved to be excellent choices for 100- and 200-yard matches, on windy days, their light bullets got blown around quite a bit at 300 yards. The 270 Winchester, 30-06 and 300 Holland & Holland Magnum were tried and while all won the occasional match, recoil made them more difficult to shoot accurately than the .22-caliber cartridges. The 250 Savage and 257 Roberts were easy enough on the shoulder, and while both won a few 300-yard matches, neither became very popular. This was mainly because no match-grade bullets were available for them. Bullets of 22 caliber designed for shooting varmints at long range were considerably more accurate than those of larger calibers.

Then, a competitor by the name of Charles Morse began making match-grade bullets of .243-inch diameter in weights of 75, 85 and 90 grains. Oddly enough, though, the dual-purpose 6mm cartridge he designed was formed by shortening the 300 H&H case to 21⁄4 inches, necking it down, and giving it a 30-degree shoulder. For picking off woodchucks at long range, the Six Millimeter Magnum, as it was called, was loaded with 50.0 grains of IMR-4350 and a 90-grain bullet for a velocity of 3,400 fps. For punching paper at 300 yards, the powder charge was reduced to 43.0 grains for a velocity of 3,100 fps. Needless to say, Mr. Morse’s cartridge failed to catch on in the game of benchrest competition.

In addition to being in charge of advertising at Marlin for many years, L.R. Wallack was an avid competitor during the early days of benchrest shooting. He was also an accomplished builder of extremely accurate rifles for that game. His very informative Modern Accuracy in Bench Rest Shooting, published in 1951, was the first comprehensive book written on the sport that he so loved. Wallack credits Mike Walker with being instrumental in the development of several 6mm cartridges suitable for benchrest competition. A design engineer at Remington, Walker developed the Remington Model 721/722 rifle as well as the Model 700 that replaced it in 1962. The 40X target rifle was also his baby.

Mike Walker was also a top-ranked benchrest competitor, and it was thought that one of the 6mm cartridges he developed was formed by simply necking up the 220 Swift case with no other change. Doing so was not exactly a new idea, as others had traveled down the same road with the 220 Swift case, although other versions were fire-formed to a less body taper and a sharper shoulder angle. The 240 Cobra developed by Homer Brown and mentioned by P.O. Ackley in his Handbook For Shooters & Reloaders Volume 1 is an example. Walker came up with his version when the plain vanilla 220 Swift was winning benchrest matches, and simply necking up that extremely strong case probably seemed like a logical thing to do. Adding icing to the cake, Fred Huntington, who founded Rock Chuck Bullet Swage (RCBS) in 1943, began making match-grade, 90-grain bullets with a diameter of .243 inch. He also sold the jackets and the swaging dies for those who wished to make their own bullets.

I started shooting in benchrest matches during the 1980s and tried a pair of extremely accurate rifles in 6mm BR Remington and 6mm PPC before finally settling on the PPC due to cases of higher quality. Among many nice people I got to know was a gentleman who had been in the game since the 1940s. He also shot a rifle in 6mm PPC, but for the sake of fond memories, he had kept a couple of rifles from the old days. Both were built by L.R. Wallack, and they still wore their Unertl 24x scopes. The 1917 Enfield action of the rifle in 220 Arrow had been modified to look exactly like a Remington Model 30 action. The 6mm Swift was on an FN Mauser action. Long story short, I bought the 220 Arrow and was allowed to spend a couple of weeks with the 6mm Swift and its owner’s RCBS reloading dies. At the time, I was loading bullets made by Ed Watson in the 6mm PPC, but also had bullets made by Walt Berger and Ed Shilen on hand. All proved to be quite accurate in a rifle built 40 years or so before I shot it. I still have boxes of those bullets.

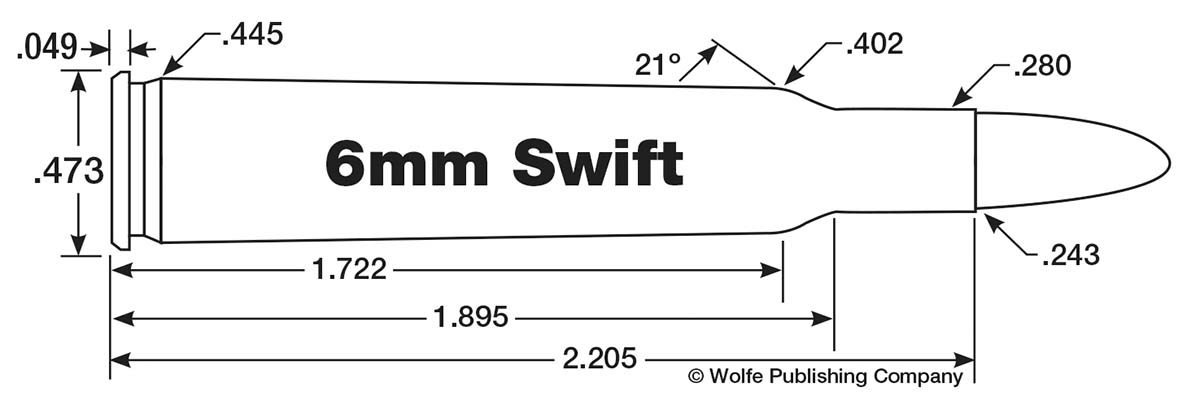

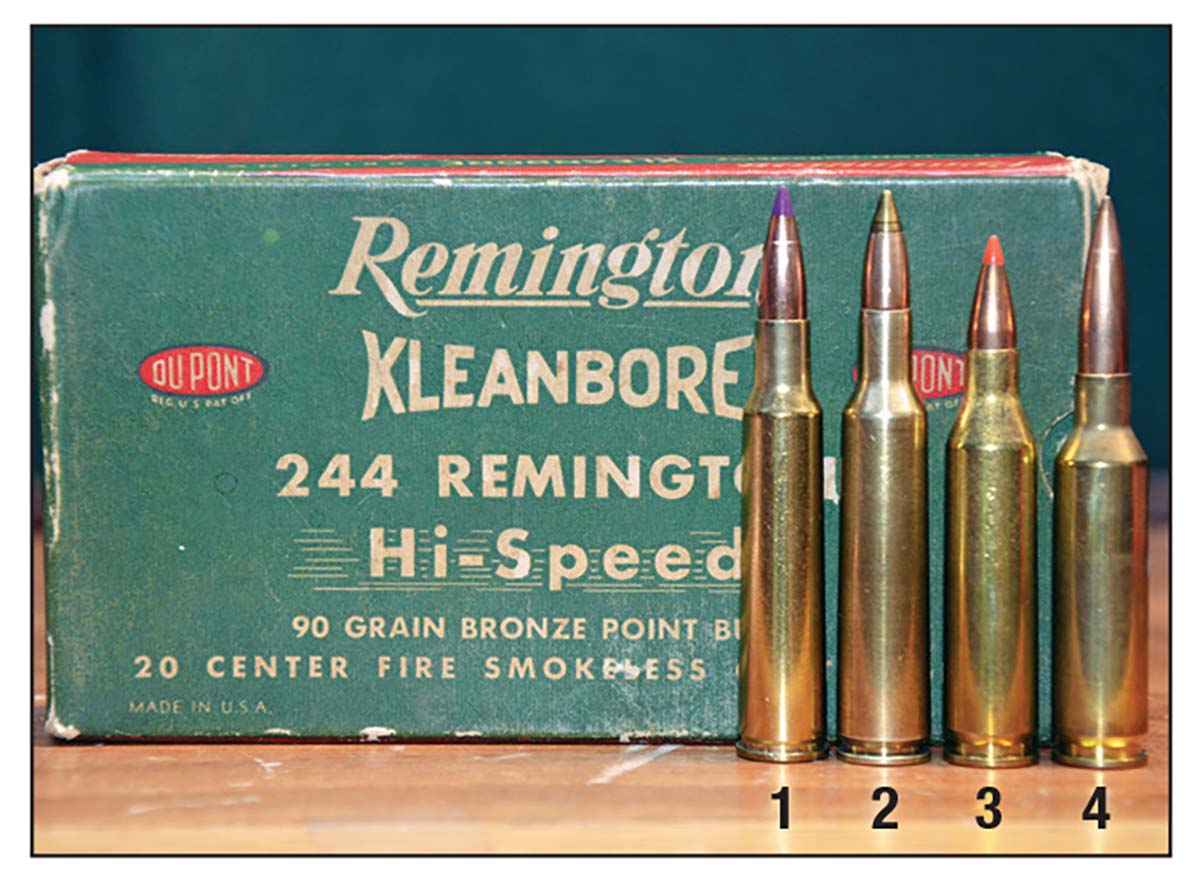

While writing this column, I compared the gross water capacities of several 6mm cartridges. The 6mm Swift (Winchester case) held 46.8 grains compared to 53.4 grains for the 243 Winchester, also a Winchester case. The 6mm Creedmoor cases made by Hornady averaged 51.2 grains. Also included was the 244 Remington, designed by Mike Walker and introduced by Remington in 1955. In the 257 Roberts case, it held 55.1 grains. Here is an interesting point. When the 6mm Swift was being developed during the 1940s, it was decided that barrels with a 1:12 rifling twist delivered the best accuracy, and that’s what Walker went with while designing the 244 Remington during the early 1950s.

Most rifles built in the past will have a 1:10 or 1:12 rifling twist rate. Due to today’s availability of extremely long-for-caliber bullets, a quicker twist is not a bad idea for a new rifle build. Hornady recommends no slower than 1:8 for its 103-grain ELD-X. In his book Ballistic Performance of Rifle Bullets, Bryan Litz says 1:8 will stabilize the Berger 115-grain VLD Hunting, but goes on to recommend 1:7.2 as optimum. Having previously found that finger-long projectile to shoot inside 0.60 inch from a Ruger Precision Rifle in 6mm Creedmoor with a 1:7.7 twist, I figured the 1:8 twist of my 6mm-06 would also stabilize it in flight. It has proven to be accurate enough.

.jpg)