Cartridge Board

6.5x52mm Carcano

column By: Gil Sengel | October, 18

Origin of the 6.5 Carcano began with the announcement of the first commercial smokeless powder compound, known as Poudre B, by French inventor Paul Vieille in 1886. All black-powder military rifles were instantly made obsolete. Within a few short years, France, Germany, Belgium and Great Britain had new small-caliber, smokeless-powder military rounds. Italy wanted to join them.

Now we encounter some strange happenings. It is known that Italy approved the 6.5mm in April 1890. I cannot find a date for the rimless case design, but since the ammunition is labeled M91 (1891), it must have been designed quickly. Some say this was original work, yet I doubt it. Consider that the M91 Carcano rifle used a Mannlicher clip loading system for which Italy paid a royalty of 300,000 lire. Then Mannlicher sold Romania its M1892 military rifle that fired a rimmed 6.5mm cartridge, and its case had the same .450-inch base diameter as the .303 British – it was formed from .303 cases! The Netherlands bought essentially the same rifle chambering and the same cartridge; today it is called the 6.5x53R Mannlicher. I would bet this was the rimmed case Italy used in its initial testing.

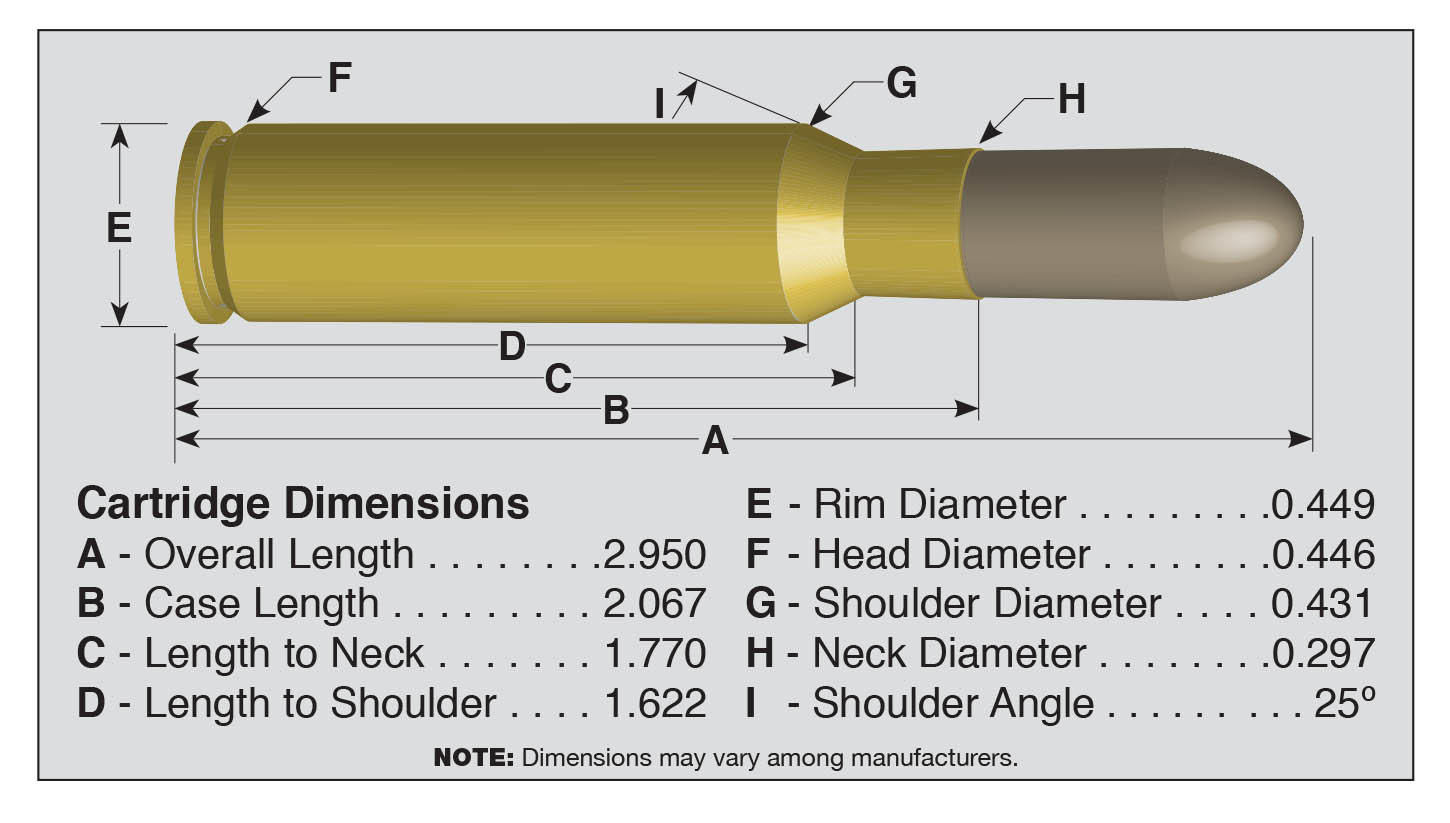

Italy’s wise decision to use a rimless case for better feeding in automatic arms resulted in an exact rimless copy of the 6.5x53R, except for a slightly shorter neck. This is the 6.5x52 Carcano. Greece later purchased its M1903 Mannlicher rifle chambered for what was called the 6.5x54 Mannlicher – simply a 6.5 Carcano lengthened to the same length as the 6.5x53R! It seems more than likely that Mannlicher (like Mauser) had to have cartridges to fire in his military rifles if he hoped to sell them. Smaller calibers and lighter bullets

Italy did, however, have a few ideas of its own. One was a wide, deep groove formed in the rear of the case head. It was added four years after production began. Some enthusiasts say it was to save a bit of valuable brass. Others insist it was to prevent a fired primer from backing out when the round was used in automatic weapons. The latter is not possible because the groove was formed when the case was drawn and before the primer was

Another unique feature was a raised ledge formed at the inside bottom of the case neck. The purpose was to prevent the bullet from being pushed farther into the case when subjected to the violent feeding cycle of machine guns.

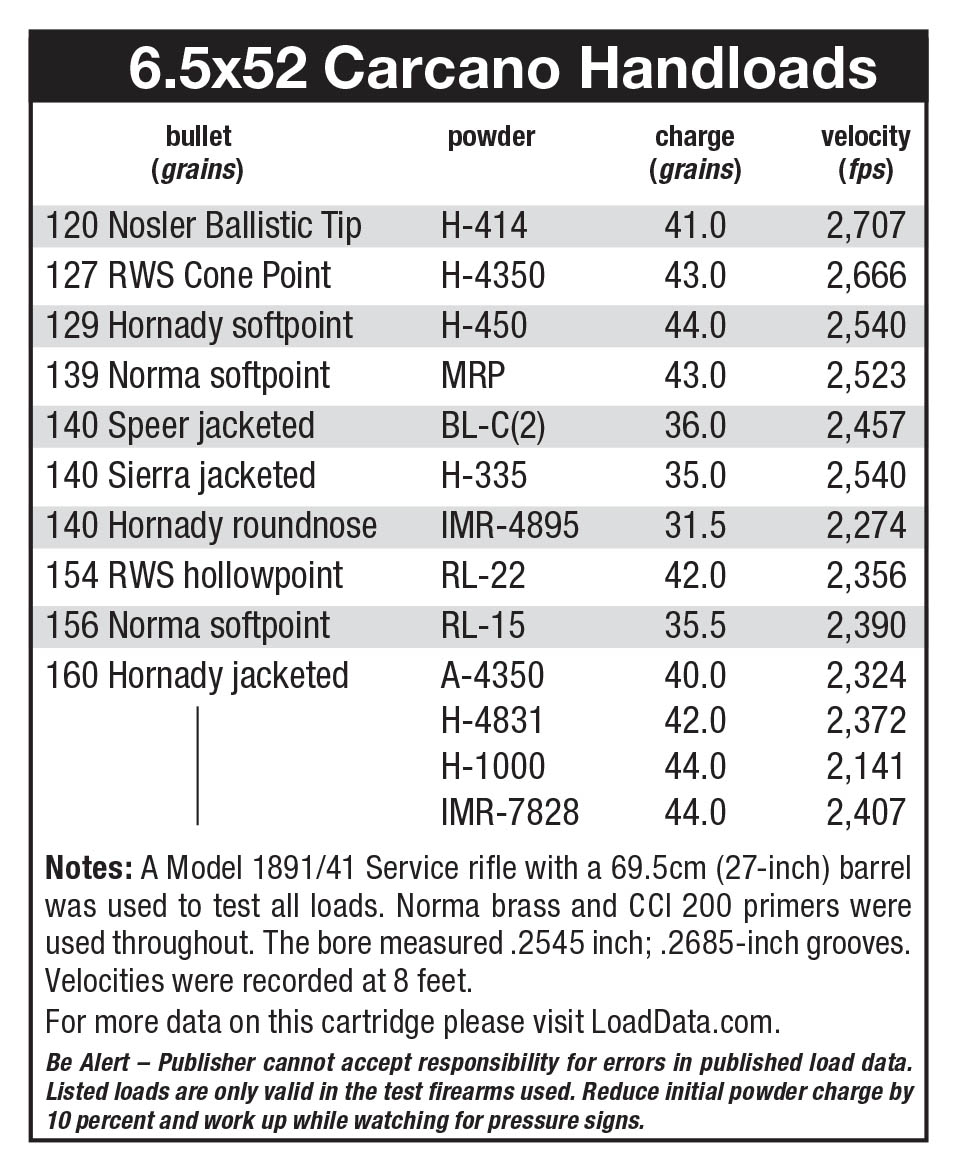

Original 6.5 Carcano loads used a 10.45-gram (161-grain, .267-inch diameter) jacketed roundnose bullet. This bullet was made by dropping flux into the jacket, adding a lead core then heating the jacket to melt the lead, fusing it to the jacket before finish-forming the bullet. Bonded core bullets are not a modern development! Propellant consisted of 30.1 grains of Number 1 Ballistite, a powder licensed from Dynamit Nobel. Muzzle velocity is given as 2,297 fps from a 30.7-inch barrel or 2,130 fps from later 18-inch carbine models.

A few modifications were made to ammunition as time passed. In 1906 a change in powder to Solenite (very close to British Cordite) gave lower breech pressure. At the same time a strange trapezoidal-shaped stab crimp was placed at three points around the case neck. This became a conventional rolled crimp just before WWII. Beginning in 1940 the cupro-nickel bullet

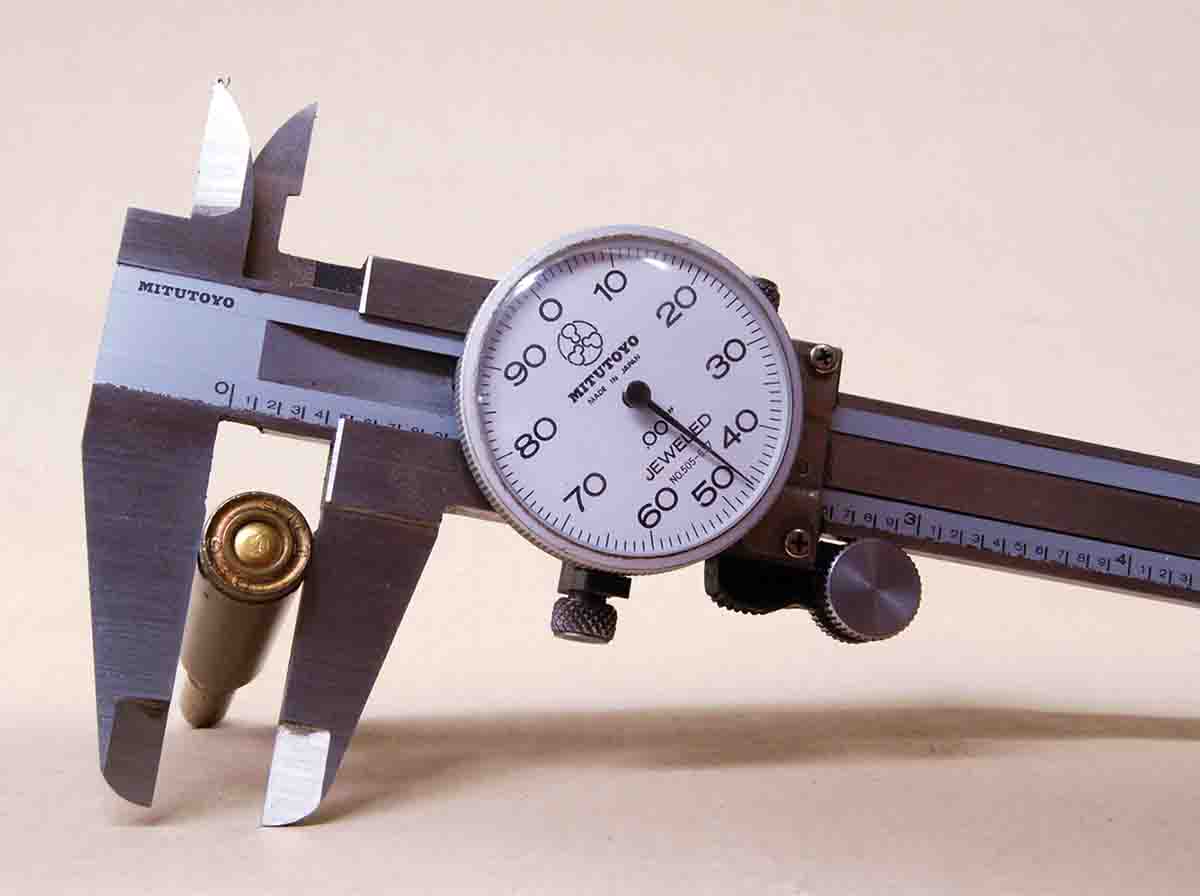

One might think handloading the 6.5 Carcano would be simple, yet that is not the case. Rifles have standard 6.5mm (.256 inch) bores, yet groove depth runs .268 inch to fire the .267-inch military bullets. Standard 6.5mm bullets today are .264 inch diameter, so accuracy varies. Hornady listed a 160-grain RN .267-inch bullet especially for the Carcano until at least 2013, but it is gone today. Norma USA offers a factory load pushing a 156-grain Alaska softpoint to 2,330 fps, and the company offers empty cases. I believe Prvi Partizan also listed empty cases recently. Proper steel jacketed bullets are sometimes seen, presumably pulled from old surplus rounds.

Accuracy of the 6.5 Carcano is often criticized, but I have some experience here, having bought one in 1962 at the military surplus store in Clinton, Iowa. Price was a few cents over $10 for a rifle and all the surplus ammunition I could carry to the truck in one trip! The bore was quite good. Exterior condition of the rifle can only be described as “battlefield abandoned,” yet it would keep all its bullets in a 12-inch circle at 200 yards and almost all at 300 yards using factory sights that are really, really crude. Nevertheless, with proper ammunition it would be fun on tip-over targets today, and it was a whole lot more pleasant to fire than my dad’s teeth-rattling ’03 Springfield!