Loading The .45 ACP (Pet Loads)

Handloading for Flexibility and Accuracy

feature By: Brian Pearce | October, 17

cartridge. The Thompson-LaGarde tests conducted during 1904 further proved the advantages associated with a .45-caliber handgun, so the army and cavalry specified that their new pistol would be .45 caliber. General John T. Thompson was clearly the driving force in the development and ballistic requirements for a “man-stopper” pistol and cartridge.

In 1904, Browning and Colt were experimenting with a “.41 caliber pistol and cartridge,” which was probably a .40 caliber due to the barrel groove and bore diameters used for their production revolvers chambered in the .41 Colt and .38-40 Winchester cartridges. At the military’s request, Browning immediately went to work on a new .45-caliber cartridge and pistol. By cutting the .30-03 rimless case (a cartridge that later evolved into the .30-06) to around .898 inch and loading it with .45-caliber, 200-grain bullets at 900 feet per second (fps), the .45 ACP was born and was housed in the newly designed Colt Model 1905 Automatic Pistol.

The military tested the new pistol and cartridge at length but wanted additional safeties and a heavier bullet. This ultimately lead to Browning designing the Colt Model 1911 pistol, which passed rigid military testing without a single failure. It was officially adopted for service March 29, 1911. Period mil-spec loads from Winchester Repeating Arms, Frankford Arsenal and Union Metallic Cartridge contained a 230-grain Ball bullet with a velocity of 850 fps. However, the velocity specification for “Ball” loads changed over the years and was last listed at 830 fps.

In spite of the .45 ACP serving as the official U.S. military issue cartridge from 1911 through 1985, when the Beretta M9 (Pistol, Semiautomatic, 9mm, M9) replaced it so that the U.S. would conform to the NATO Standardization Agreement, the .45 ACP has remained in continuous service. Its widespread use among U.S. shooters is remarkable, and as a result it often ranks as the most reloaded pistol cartridge, based on annual die sales.

The popularity of the Model 1911 pistol is also remarkable, with literally dozens of manufacturers offering guns that vary substantially in quality and price. Those of poor quality (or design) can display reliability issues or are limited as to bullet designs that will feed correctly. In other words, loads (including factory loads) containing flatpoint or hollowpoint bullets often do not feed reliably. High-quality guns feed a variety of bullet profiles without incident. The .45 ACP has also become popular in more modern pistol designs (please note that I did not say “better”) that are often of polymer construction. These designs are generally very reliable and feed cartridges with a variety of bullet profiles when loaded to correct specifications.

To develop the accompanying .45 ACP loads, I used a Wilson Combat Model 1911 Protector, which is of top-notch quality and design. It offers the same features (along with many additional ones) that were built into costly custom Colt pistols during the 1970s. Features include a match-grade barrel, lowered and angled ejection port, precision fit barrel and bushing, extended match trigger, serrated slide, high-ride beavertail grip safety with corresponding lightweight, slotted hammer, combat-style tritium sights, flat mainspring housing, 30 lpi checkered frontstrap and an extended Bullet Proof thumb safety. The machining and tolerances of the Wilson pistol are impressive. Its accuracy guarantee is one inch at 25 yards, which this gun has proven capable of, making it a great option for testing loads. Furthermore, I have owned the gun for many years, and it has offered outstanding reliability.

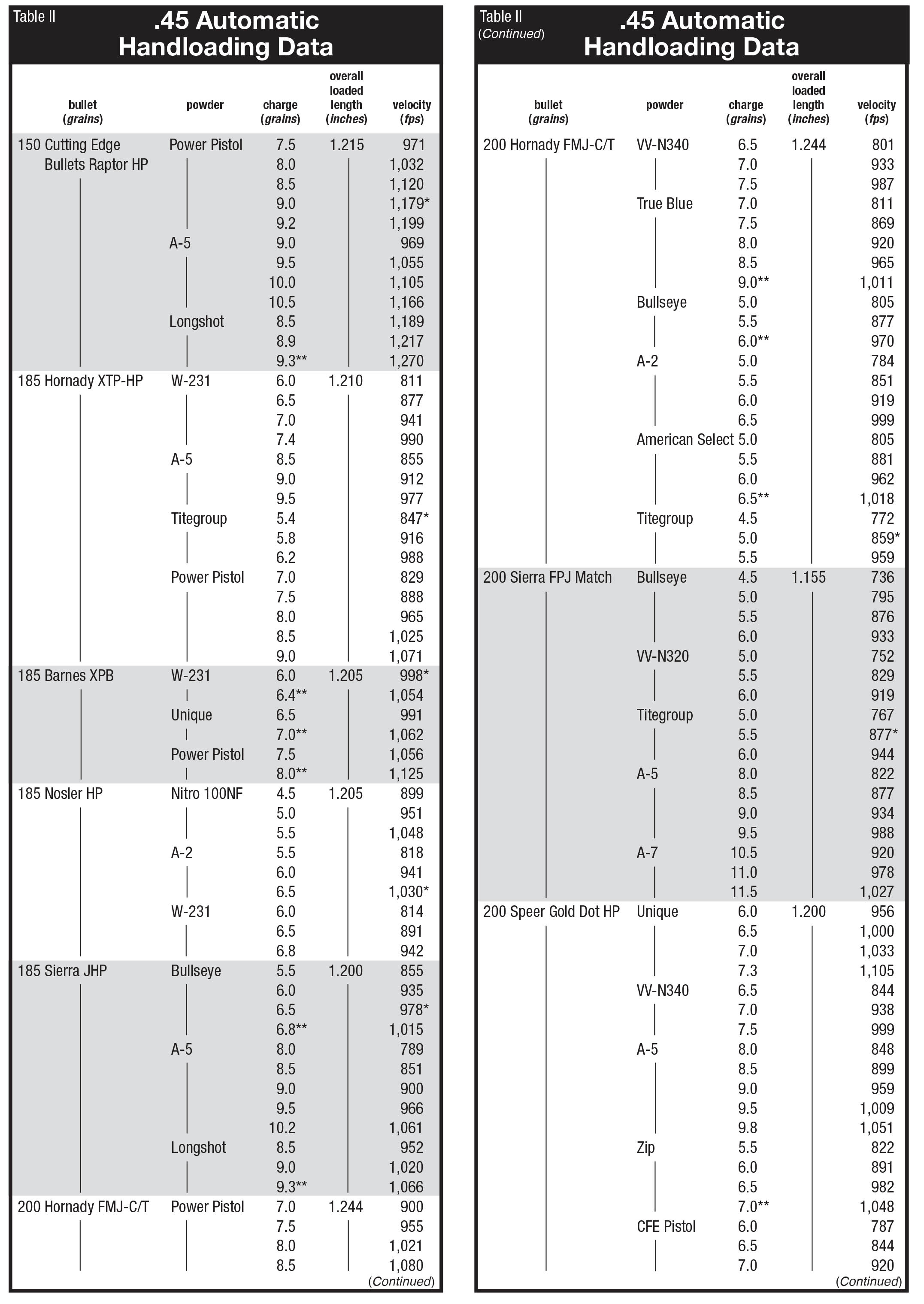

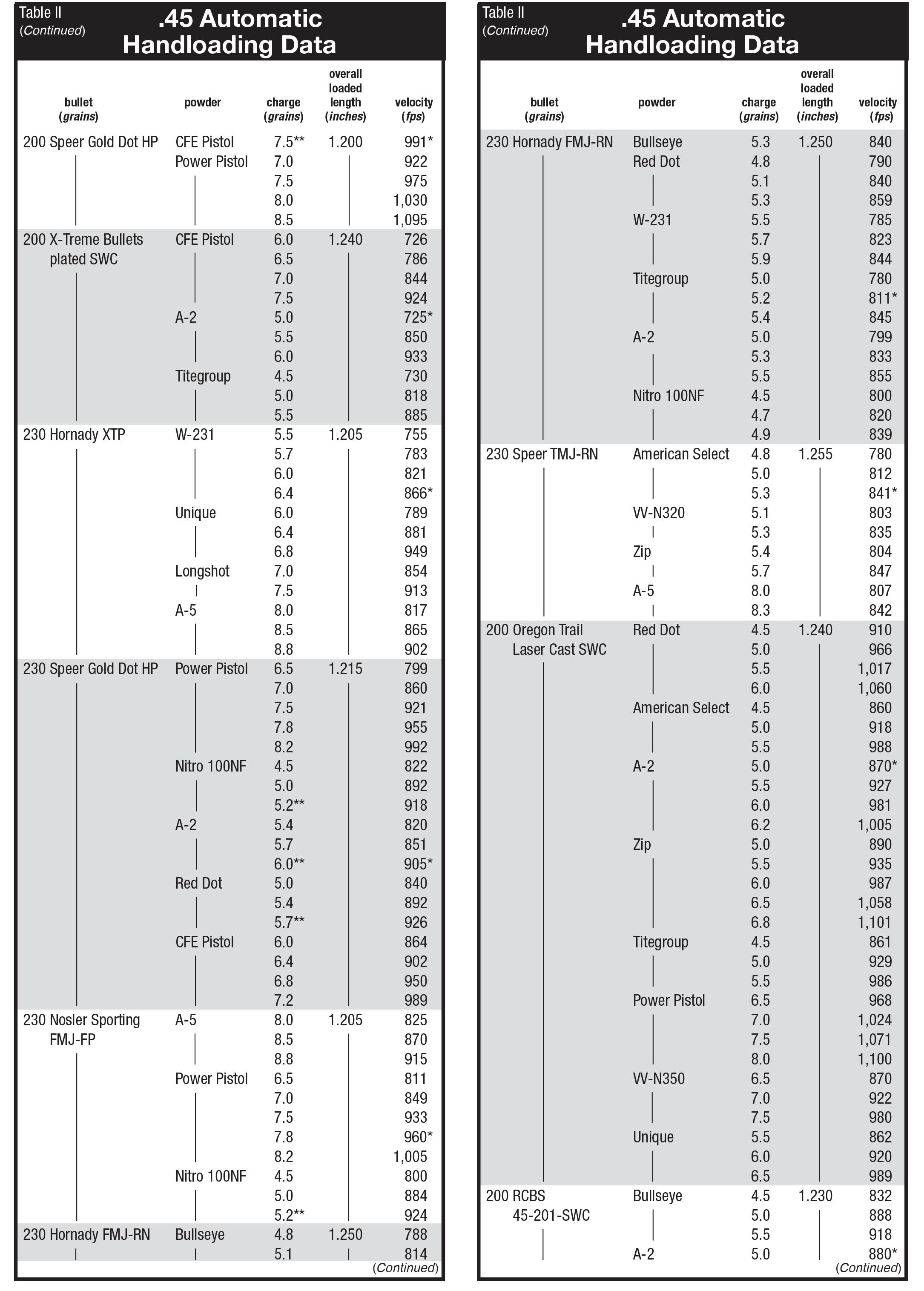

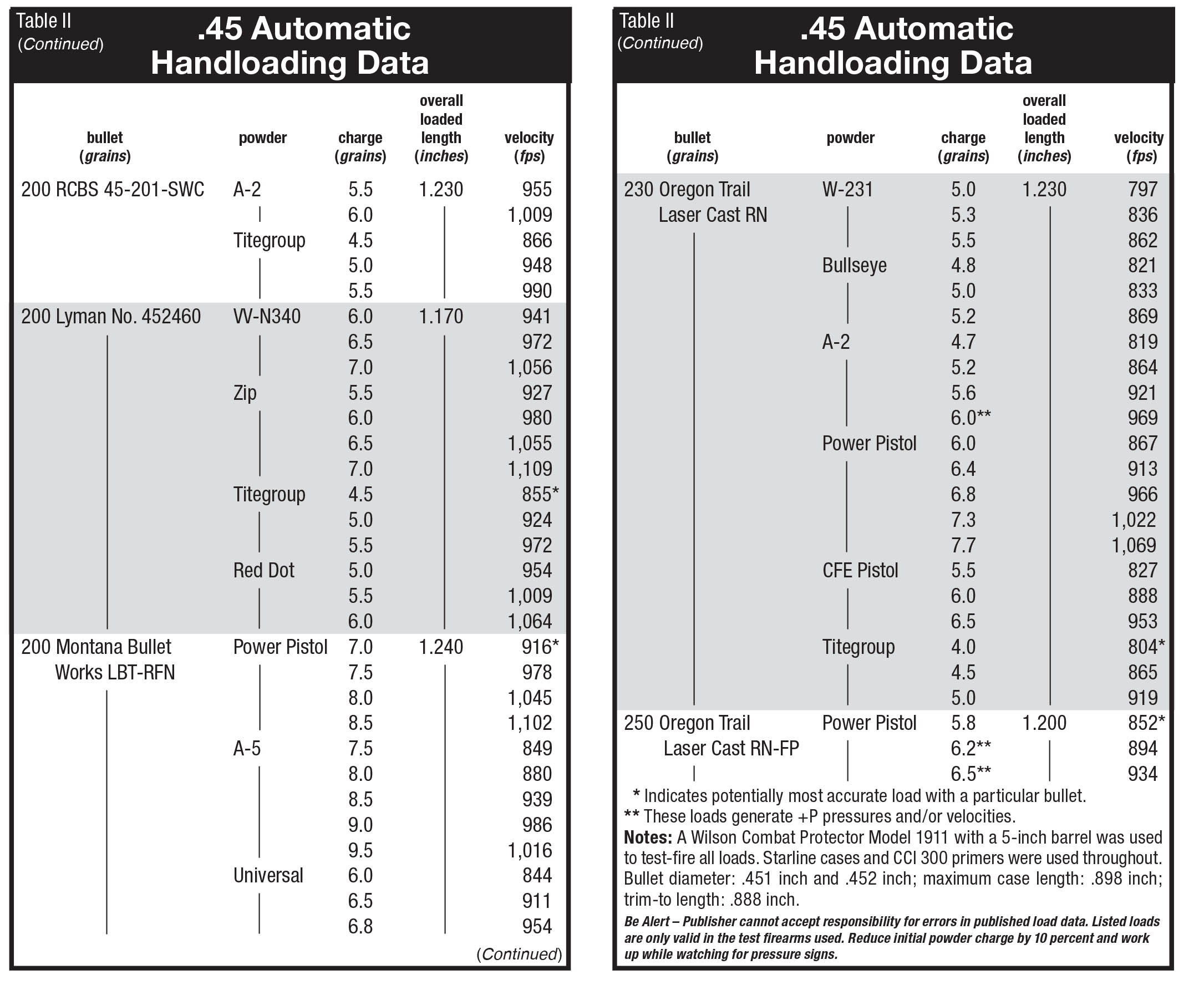

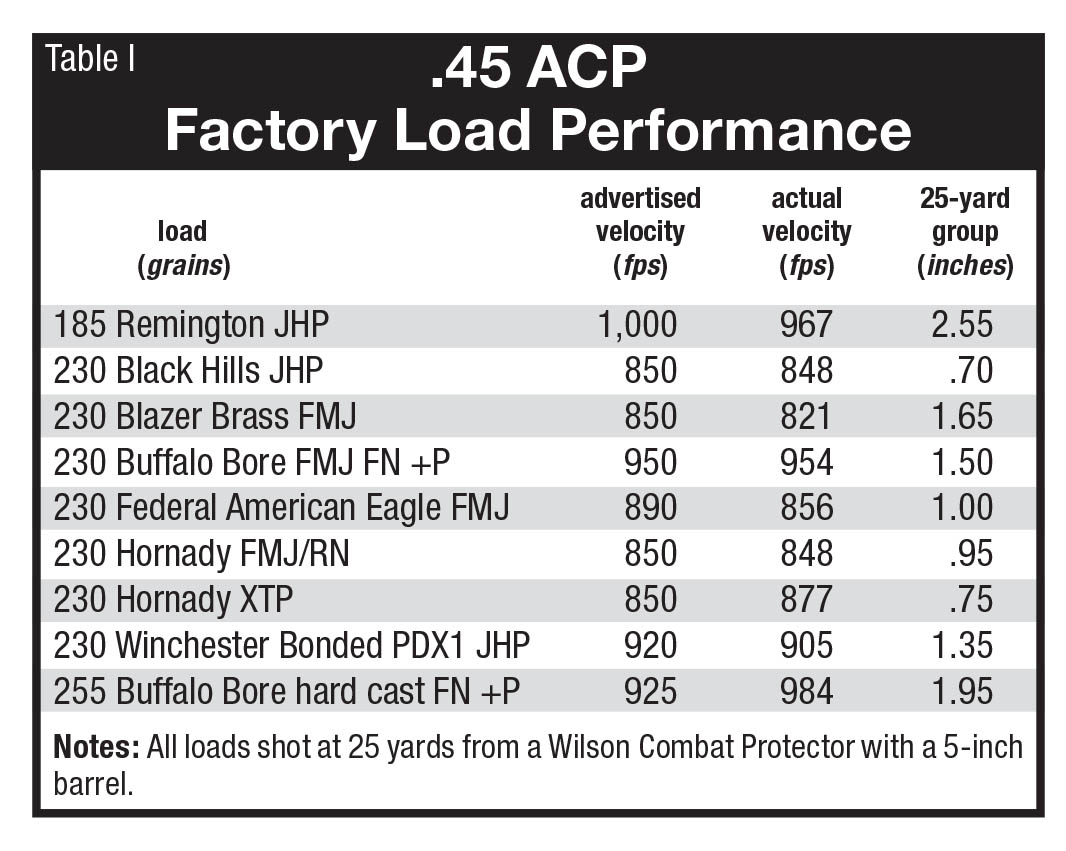

A variety of factory loads were tested for accuracy and velocity as a comparison to the handload data in the accompanying

Current industry maximum average pressure is established at 21,000 psi, while maximum for +P loads is 23,000 psi. While most guns are rated for +P loads, it is best to check with the manufacturer to make certain that a given model is rated for +P pressures. Even if a particular model is suitable for +P loads, be certain that the correct (pound-rated) springs are installed and are fresh or not worn out. The primary focus of this article is standard-pressure loads; however, a few +P loads are included and are marked accordingly. It is noteworthy that by using select powders, +P performance was possible while maintaining standard pressures.

The rimless .45 ACP headspaces on the case mouth, which is a subject that has sparked considerable discussion and debate. Some argue (and they are correct) that cases shorter than industry specification of .888 inch will still function and fire in most autoloading pistols as the extractor holds the case back against the breech face and allows the firing pin to strike the primer. While this is certainly true, accuracy will generally suffer and misfires can still occur. Furthermore, if cartridges are fired in a double- or single-action revolver without moon clips, misfires will most certainly occur. To further understand the importance of using cases that are within industry specifications and crimped properly, take the barrel out of your pistol and insert a

Based on the information above, it is important to apply a taper crimp rather than a roll crimp. This aids in smooth cartridge feeding, helps keep bullets in place (or prevents deep seating) when cartridges are cycled fast through autoloaders and helps obtain proper powder ignition. The crimp should measure .470 inch, which can be measured at the case mouth using blade calipers. By the long sloping nature of a taper crimp, it is important to apply the crimp as a separate operation after the bullet is seated to the correct overall length. This will result in improved accuracy and prevents case and bullet damage that usually occurs when bullet seating and crimping are attempted as a single step.

Like most comparatively short pistol cartridges stoked with fast-burning powders, bullets in the .45 ACP must be seated to the exact listed overall cartridge length, or pressures can change substantially. Various tests have been conducted that illustrate changing bullet seating depth by as little as .050 to .100 inch can literally double chamber pressures. This can result in blown cases and even damage to guns, shooters or bystanders. I recently examined a Model 1911 that had been damaged because the shooter was loading a large quantity of ammunition on a progressive press, and bullet lube built up inside the seating die, causing bullets to seat more deeply than desired. Several hundred rounds were loaded before the error was caught. He cleaned and adjusted the die but chose to fire the handloads containing the deep-seated bullets, which resulted in a blown case and damaged gun.

Before selecting a given load based on its velocity or even accuracy, I suggest considering how clean it burns, which can be an important part of how reliable a gun is. I discovered years ago that a major ammunition factory had produced 10,000 rounds of .45 ACP that was slightly out of its specifications in regard to bullet seating. The ammunition was tested for velocity and pressure and was fine in this regard, but it could not be sold through normal sources. I made a deal and procured it. It was accurate and gave low extreme spreads; however, the powder used was a poor choice, especially for high-volume shooting. It was fired through several of my tightly fitted custom and factory-custom Model 1911s, only to discover that it didn’t take long until they were so dirty that they would not function. I switched to a custom Colt that was intentionally built with looser tolerances, and it didn’t function much longer than the custom guns. Finally, these loads were tried in a Glock Model 21, one of the most reliable autoloading pistols ever designed, but it too prematurely succumbed to the powder fouling. The remainder of the ammunition was ultimately used up in revolvers. A few examples of powders that burn cleanly include Hodgdon Titegroup, CFE Pistol, Alliant Power Pistol, Bullseye, Accurate No. 2, Ramshot True Blue, Winchester 231 and Autocomp.

I have checked velocity changes associated with different primer brands, and standard versus magnum. The difference can vary

In recent years, some companies have begun constructing .45 ACP cases to utilize small pistol primers primarily for lead-free primed, nontoxic factory ammunition intended for indoor ranges. Using these cases with the accompanying data will change velocities (usually slower) and pressures. Starline cases with large pistol primer pockets were used exclusively with the accompanying data.

Bullet selection for the .45 ACP is broad and includes jacketed, plated, hard cast, swaged lead and even expanding solid copper. Substituting bullets that are of the same weight with a given powder charge can yield significantly different results and is generally not recommended. Reasons include bullet design and seating depth that can change powder capacity, bullet material that can change pressures and velocities, bullet diameter variances, or in regard to swaged lead bullets, they are not designed for higher velocities which can result in barrel leading and poor accuracy. Bullet bearing surface is not often discussed, but can vary significantly, even from the same manufacturer. For example, select 230-grain military profile “Ball” bullets have a significantly shorter bearing surface than popular 230-grain JHP bullets. This will change pressures and velocities if the same powder charge is used with each.

to be used in rifles or carbines, try near-maximum loads and a slower-burning powder that yields the highest velocity with a given bullet. And before handloading very many cartridges, be certain bullets are reliably clearing the barrel.

.223 Remington “Pet Loads” Correction

In the last issue of Handloader No. 309 (July/August 2017), at the top of page 62, second sentence, the word “only” was mistakenly added to the original text, as was the word “shot” (single-shot) near the bottom of the second to last paragraph on page 67. All loads were shot with a 1:9 barrel twist. We apologize for any confusion this may have caused.