Mike's Shootin' Shack

The Miracle of Primers

column By: Mike Venturino | June, 21

I also find it miraculous that primers can be made in such vast quantities. I have no idea as to yearly production output of primer manufacturers such as Winchester, Federal, CCI and Remington. However, I read in one book that in mid-1944, Germany was producing 220,000,000 rounds of rifle cartridges “PER MONTH.” Back in the 1990s, I was invited to visit Remington’s ammunition factory in Arkansas and was floored to see that some parts of primer manufacture were still done by hand. Yet in normal times, most stores stocking handloading components keep large quantities and varieties of primers on hand.

It’s also amazing that the actual primer used can make such a difference in ammunition performance. Plinking or ringing steel as I often do for relaxation, requires little in the way of performance, so most any primer suffices. On the other hand, in my chosen sport of Black Powder Cartridge Rifle Silhouette, to be competitive, a single-shot rifle with exposed hammer must group no larger than 1.5 MOA out to 500 meters. This is with black powder and lead alloy bullets.

Experienced competitors all have their favorite primers, settled upon after considerable test firing. I have come to prefer CCI-BR2 (Bench Rest Large Rifle) primers. My shooting partner Ted Tompkins, who has won more accolades than I, favors Federal 210 Match primers. Some very fine shooters in the sport use pistol primers of one sort or another. At times, in my paper target shooting of 12-shot groups at 300 yards, different primers have been given similar velocities, shot-to-shot variations and standard deviations. Yet the groups vary greatly in tightness. Go figure.

Another miracle is the vastly different types of primers. The four basic groups are large rifle, large pistol, small rifle and small pistol. Then those groups again can be subdivided into standard or magnum. Novices think magnum primers are needed for magnum cartridges. This is not so. They are meant for slower burning or hard-to-ignite powders. Then there are the “match” primers such as the aforementioned CCI-BR2 and small rifle size CCI-BR4. Remington’s No. 7½ Bench Rest Small Rifle primers are greatly respected, as are Federal’s line of “match” primers. CCI also offers its military spec primers, #34 for large rifle and #41 for small rifle. In doing the shooting for my book SHOOTING WORLD WAR II SMALL ARMS, I experienced a slamfire with my semiauto Soviet SVT40 7.62x54mmR and my semiauto German K43 8x57mm. That situation can be dangerous, so those rifles and my M1 Garands only get CCI #34 primers now.

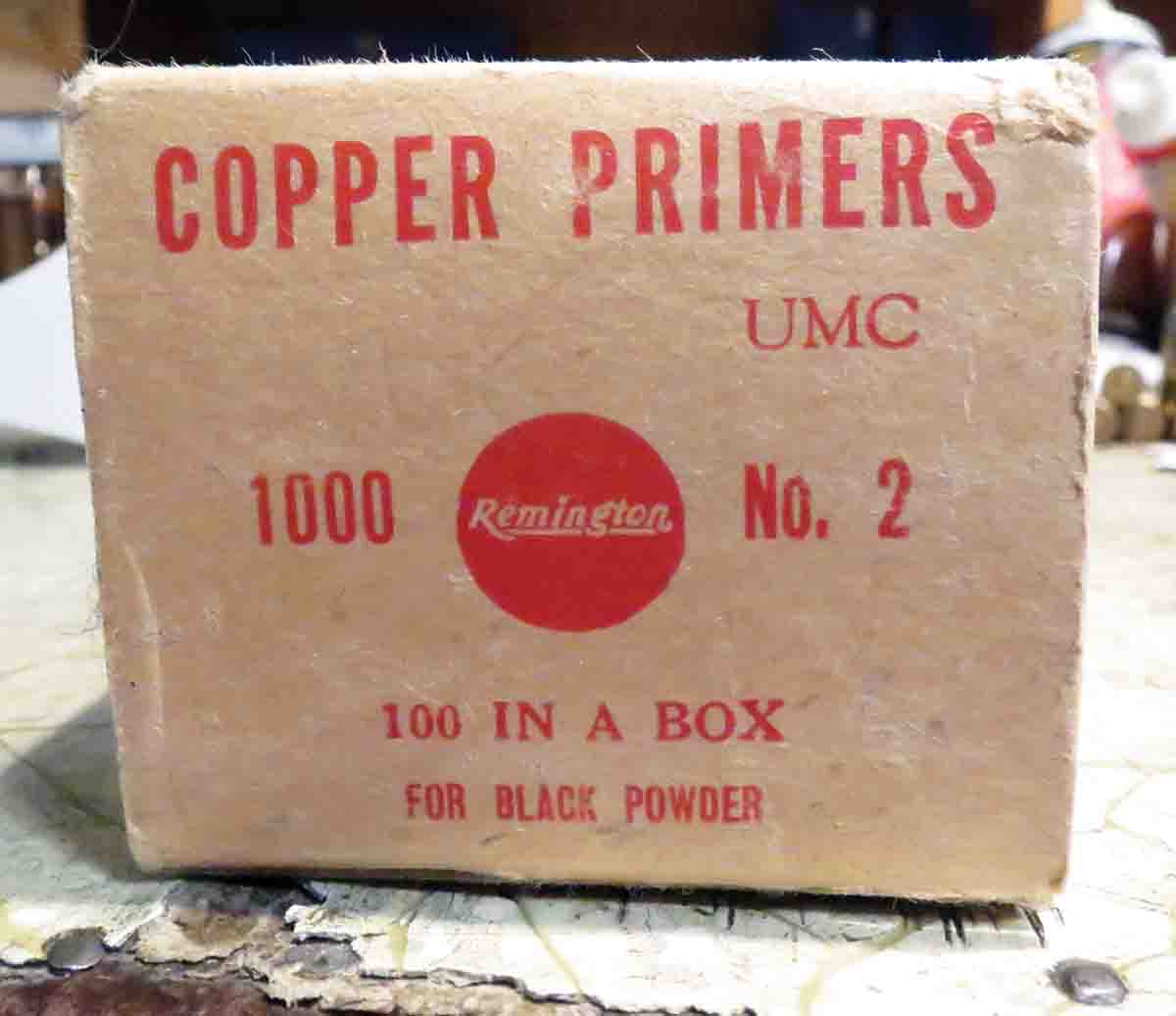

In bygone times, some primers were intended specifically for black-powder loads. I have an intact 1,000-count box of Remington No. 2 primers. The temptation to open that box and try some of those “black powder primers” has been great, but I’ve resisted. Of course in Europe, Berdan primers were the standard for decades. Those are meant for cases with an integral anvil in the primer pocket and multiple flash holes. It seems that Boxer primers are growing in popularity over there, with companies such as Norma in Sweden, Lapua of Finland and Prvi Partizan of Serbia all using single flash hole cases meant for Boxer primers.

Primers must have been a confusing mess to early American handloaders. In the 1870s, Government .45-70 and .45 Colt and .45 Smith & Wesson ammunition appeared to be rimfire. Actually, those copper cases had internal centerfire primers, and some ammunition such as the .38 WCF/.38-40 that today is standard with large primers, were then loaded with small ones. In more recent times, the .357 Magnum was loaded with large pistol primers whereas today, small pistol primers are standard for it.

A primer fact that became known to me about a dozen years ago is that large pistol and large rifle primers differ dimensionally, yet small rifle and small pistol primers do not differ. For 40 years I thought that both sizes differed dimensionally in regard to rifle or pistol types. Primer pockets in rifle cartridge cases are slightly deeper because large rifle primers are slightly taller. However, primer pockets for small size primers are the same regardless as to rifles and handguns.

Another miracle is that primers are so powerful. I have a .222 Remington Magnum case in which a fellow seated a primer sideways. In his SAKO rifle, it ignited without setting off the powder charge. However, it damaged the rifle’s extractor. Just before this writing, I managed to do something never done before in my 54 years of handloading. I left the powder out of a .32-20 case. That round’s primer pushed the 120-grain lead alloy bullet about 4 inches into the Colt SAA’s barrel.

While writing this, a gent asked me how I was set for primers. I replied, “Good.” He then wanted me to sell him some, and when I declined, he accused me of hoarding them. “Nope,” I said, “Whenever I bought one of my World War II fullautos, I also bought several thousand primers suitable for it. Stocking up when primers are plentiful isn’t the same as hoarding when there is a shortage.”