Handloading The 6XC

A High Power Cartridge With Versatility

feature By: John Barsness | February, 18

Over the next few decades, however, more long-range target shooters wanted to use heavier, more streamlined 6mm bullets, requiring even faster rifling twists. This was part of an overall trend toward small-caliber, lighter-recoiling target rounds. Lighter powder charges and bullets not only reduce recoil but increase barrel life. The 6.5-284, for example, had a run as a top long-range target round in the early 2000s until the 6.5 Creedmoor took over. The Creedmoor uses about 10 grains less powder, so barrel life is considerably longer and recoil is milder.

While 6.5mm barrels always had faster rifling twists due to the 155- to 160-grain bullets used in most early 6.5mm military

This eventually affected some existing 6mm target cartridges. The 6mm BR Remington appeared as a wildcat in the 1960s, based on Frank Barnes’ .308x1.5 wildcat, the .308 Winchester case shortened to 1.5 inches. Remington standardized the 6mm BR in 1988 as a commercial competitor to the 6mm PPC.

By then the 6mm PPC had taken over short-range benchrest competition, but the case was too small to produce the higher velocities needed for longer ranges. Plus, most American long-range target shooters still believed in large-caliber cartridges, whether for bulls-eye or benchrest competition, due to believing heavier bullets drifted less in the wind. Eventually, however, they realized the two factors affecting wind drift were ballistic coefficient (BC) and muzzle velocity. If BC was high enough, bullet weight was irrelevant, and the move began toward 6.5mm and 6mm rounds.

First, the cartridge had to fit and feed from the standard 2.84-inch “short” magazine used today. Initially he tried the .243 Winchester, but it had appeared in 1955, long before any of today’s ultra-streamlined, heavier competition bullets. When seated deeply enough to fit in a 2.84-inch mag-azine, their ogives ended far from the rifling in the standard .243 chamber. While a longer magazine could be used, that meant additional costs and gunsmithing.

Eventually Tubb decided to design his own 6mm cartridge, choosing the .22-250 Remington case, the .250-3000 Savage necked down, because its case is over .1 inch shorter than the .243’s case. A bunch of recent cartridges have been designed on the .250 Savage case, including the 6.5mm Creedmoor. Cartridge designers don’t often acknowledge this, apparently because the .250 appeared more than a century ago; too long for its role to be remembered.

The .250 has a case length of 1.912 inches and a 26.5 degree shoulder, but like many early smokeless rifle cartridges the case walls are tapered for easier extraction. In 1920 Savage shortened the same basic case a little, gave it more parallel walls with a 30-degree shoulder and necked it up to .30 caliber to produce the .300 Savage. In 2007 Thompson/Center Arms modified the .300 Savage case slightly, by moving the shoulder forward and lengthening the neck, resulting in a 1.92-inch case length – almost identical to the .250 Savage.

The .30 T/C never became very popular because it basically reproduced .308 Winchester ballistics in a slightly shorter case, and

Tubb, however, developed what he called the 6XC using a slightly different route. He called his original wildcat the 6mmX (for the X-ring on a High Power target) – essentially the .243 Winchester shortened by .145 inch, resulting in room to spare in a 2.84-inch magazine even when loaded with long, high-BC bullets. Plus, it had a longer neck. Cases were formed by running .22-250 Remington brass into a shortened .243 die, then fireforming in the 6mmX chamber.

Eventually Tubb decided a 30- degree shoulder would be even more desirable. Thirty degrees has been semi-standard on “accuracy cartridges” going all the way back to the .219 Wasp, the shortened and blown-out .219 Zipper round that dominated benchrest matches right after the Second World War. The use of modern electronic pressure equipment has demonstrated that a 30-degree shoulder results in less pressure variation than any other angle, and hence lower velocity variations. It is also steep enough to provide plenty of resistance against the blow of the firing pin, resulting in less case stretching and longer case life.

The 30-degree variation was called the 6mmXC, soon shortened to 6XC. The combination of a sharper shoulder, longer neck and slightly less powder capacity than the .243 Winchester reduced throat erosion, usually doubling barrel life. The 6XC’s case dimensions also bypassed another mechanical quirk called the “dreaded donut.”

The “donut” is a ring of thicker brass at the the base of the case neck. It occurs when brass from a smaller-caliber cartridge is necked up, or when a case is fired and resized a number of times. Both cause the thicker brass of the shoulder to become part of the neck, constricting the shanks of bullets seated deeply enough to encounter the donut and resulting in erratic pressures that affect accuracy.

The 6XC proved so successful in High Power shooting (due in part, of course, to Tubb’s shooting skill) that Norma eventually started producing cases and even ammunition. In fact, it’s approved as a factory round by the Commission Internationale Permanante (C.I.P.), the European equivalent of SAAMI.

The Norma brass bypassed the initial formation of the donut caused by necking-down .22-250s, but if anybody wants to form 6XC cases from less-expensive brass, .22-250s still work.

While my competitive shooting is limited to informal (almost accidental) matches, I do quite a bit of varmint shooting – especially for prairie dogs – these days with a CZ 527 .17 Hornet and a Remington 700 .204 Ruger. I also like to do some long-range shooting with larger cartridges, partly because prairie dogging is one of the best ways to practice shooting in the wind.

Back in the late Paleolithic Age the .243 Winchester was considered a fine prairie dog cartridge, but these days most shooters think it burns out barrels too quickly. Aside from the .243, I’ve used a bunch of other cartridges from the .22-250 to the 6.5-06 for long-range shooting but so far had not found exactly the right combination of accuracy, lighter recoil and wind resistance.

A relatively heavy 6XC sounded like it might be worth a try, so I called gunsmith Charlie Sisk, who recently moved back to his native Kentucky. A few years ago Sisk built a rifle for me and my wife, Eileen, on one of a few “Remington 700 footprint” bolt actions he put together using one of his aluminum, adjustable STAR stocks. It was fitted with two barrels that I could switch using my own vise. We had both used the .22-250 Remington barrel for varminting, and I had used the .308 Winchester barrel for a considerable amount of range experimenting.

The rifle weighs 12 to 13 pounds, depending on the specific barrel and scope, and seemed like an ideal platform for a 6XC. Sisk happened to have a reamer, plus a 1:8 twist Lilja barrel in the second-heaviest contour Lilja makes, No. 7. He finished the barrel at 26.5 inches, about average for 6XCs used in competition, and with a 3-10x 42mm Nightforce SHV scope the rifle weighs exactly 13 pounds.

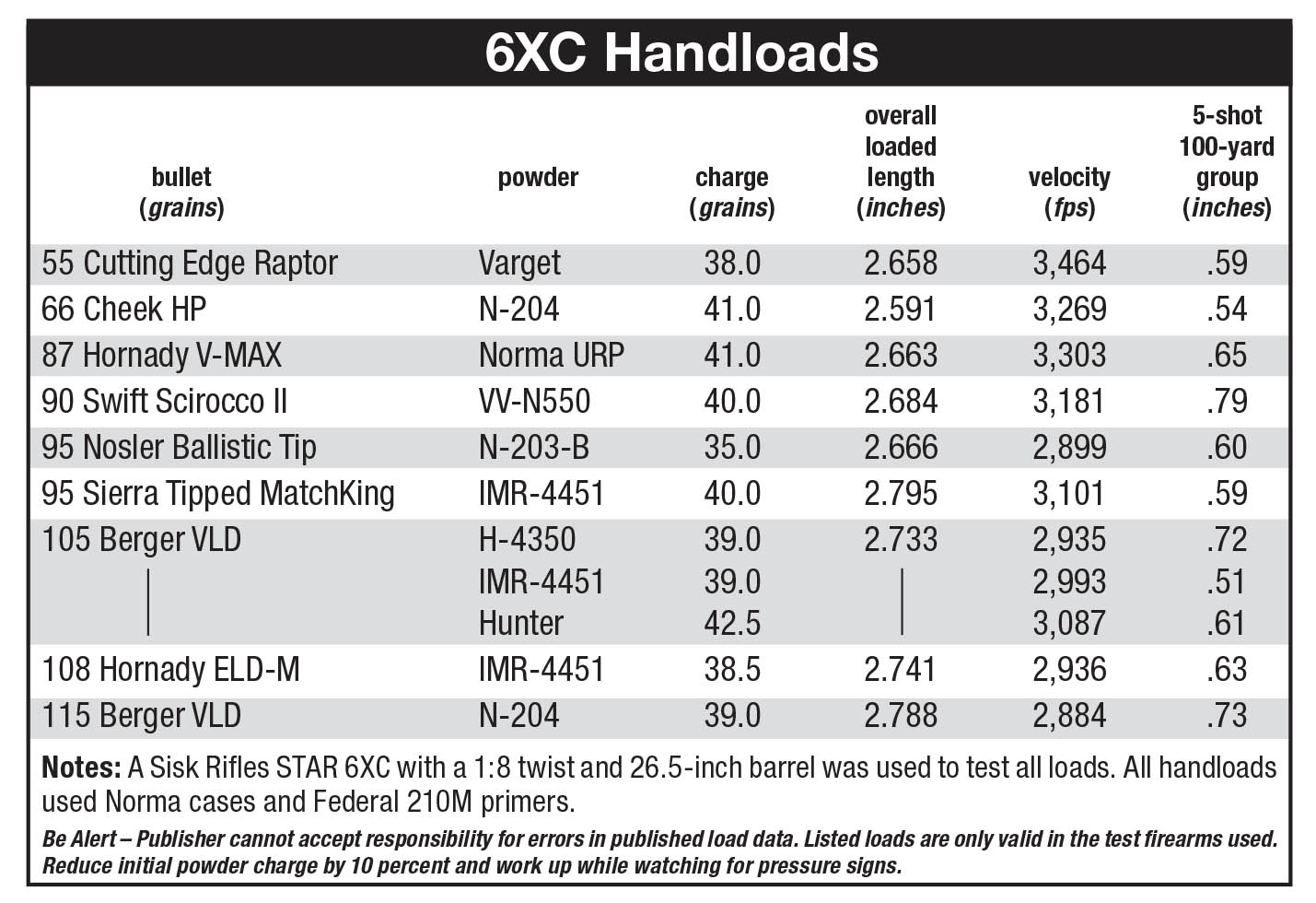

During the rebarreling I had acquired 100 new Norma cases along with a set of Redding Type “S” Match dies, and had researched handloads. Both Norma and Berger include the 6XC in their data, but neither lists the powder used by most competitive shooters, Hodgdon’s H-4350. With Norma this is understandable, but it is somewhat odd of Berger, since Tubb wrote the cartridge introduction for its manual.

Most competitors use 105- to 115-grain boat-tails, and the charges of H-4350 are often pretty warm. David Tubb keeps adding H-4350 until the case-heads show ejector-hole marks, then reduces the charge half a grain; his 115-grain load gets 3,050 fps from a 27-inch barrel. Other shooters load up to 41.0 grains of H-4350 with 105- to 108-grain bullets, though most seem to use around 39.0 grains.

Shooting tests started in February 2017, so there was plenty of time to work up a load for spring prairie dog shooting. I decided to start with H-4350 and IMR-4451, the Enduron powder that comes very close to duplicating H-4350 performance. Since H-4350 recently became hard to find (something Hodgdon’s Ron Reiber told me is primarily due to the popularity of the 6.5 Creedmoor), I’ve been trying IMR-4451 in my handloads that previously used H-4350, and so far have found it works just as well and sometimes better. Ramshot Hunter was also tried because Berger’s data showed it provided the highest velocities for any bullet weight from 95 to 115 grains.

Initial trials featured Sierra 95-grain Tipped MatchKings, Hornady 108-grain ELD-Ms and Berger 105- and 115-grain VLDs. In my rifle IMR-4451 proved to be the top all-around powder for heavier bullets by a small but noticeable margin. The “light” MatchKing was included partly because field reports indicated the Sierra would be most likely to expand on prairie dogs. It did, often spectacularly, especially at ranges out to 300 yards (I started close, to make sure it would expand before moving to longer distances), but the bullet also expanded well at more than 500 yards.

With the mild recoil from the 13-pound rifle, it was easy to spot shots through the Nightforce scope, and the thin IHR reticle and excellent optics also made aiming at small targets easy, even at extended ranges.

My loading room also contains a pile of Winchester .22-250 Remington cases acquired in a really good deal, and I resized and fireformed about a dozen. Their average weight was within a grain of the Norma cases, and they performed almost identically with a couple of the listed loads but weren’t quite as uniform in weight or neck thickness.

The 6XC would of course also work fine on deer-sized game, so several hunting bullets were included in the loads. For those who prefer zippy muzzle velocities, the monolithic Cutting Edge 55-grain Raptor would be a fine choice. (Eileen used a 40-grain .224-inch bullet from a .22-250 to make an instant kill on a pronghorn a few years ago. The barreled action of the Sisk rifle also fits in a synthetic Remington VTR stock, bringing the total weight to less than 10 pounds, making the rifle reasonably packable in pronghorn country. Maybe next year!