Holland's .300

A Century Old - and Still Super

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 22

The .300 Holland & Holland, I would contend, is neither. Nor is the venerable Winchester Model 70 (circa 1952) I used to test it. The cartridge surprised me with its power, and the rifle with its accuracy.

Ballistically, it just matched the .280 Ross’ 150-grain bullet at 3,000 feet per second (fps), but had the added advantage of being available with heavier bullets. Originally, the 180-grain bullet had a velocity of 2,700 fps and the 220 grain, 2,350 fps, which put it in a class by itself. At the time, the only comparable American cartridge was the .30 Newton, but rifle production for it ceased in the early 1920s.

Almost immediately, Western Cartridge Company began offering .300 H&H Magnum ammunition, and in 1935, Ben Comfort established it among American shooters by winning the 1,000-yard Wimbledon Cup match with a custom rifle. Shortly after, Winchester began production of the Model 70 bolt action and listed the .300 H&H Magnum among its early chamberings. With the Wimbledon win, the new Model 70 and excellent Western ammunition, the .300 H&H was away to the races.

For Americans, it was the beginning of the belted magnum era, and the race to outdo Holland’s .300 with ever more powerful .300s. Most prominent (and powerful) was the .300 Weatherby Magnum (1944). When Winchester’s .338 was introduced in 1958, wildcatters immediately necked it down to create the .30-.338 Magnum, which became very popular. Norma more or less legitimized the .30-.338 in 1960 with its .308 Norma Magnum, and this was followed by the .300 Winchester Magnum in 1963. By 1965, the .300 H&H was decidedly old hat.

The most common accusation was that it was not powerful enough, outdoing the .30-06 by only 200 fps in most bullet weights, while being too long for standard actions. Except for the Weatherby, the cartridges named above could all fit into a standard .30-06 action. Then there were related complaints about case- stretching because of the taper and long shoulder.

As for the shape of the case, it was deliberate. First, the British did most of their big-game hunting in Africa and India, where heat could become intense. They wanted to avoid excessive pressures and sticky cases; as well, the shape was perfect for accommodating long strands of Cordite. Finally, the long, tapered cartridge fed like a dream, and could be threaded into the chamber in almost total silence. These are all important considerations when hunting big game on the sweltering plains or at close quarters in thick bush.

Here’s one additional point regarding velocity. Frankly, to me, the complaint makes no sense. Based on factory loads, a shooter can have velocity with a 180-grain bullet of 2,620 (.308 Winchester), 2,750 (.30-06), 2,880 (.300 H&H), 2,960 (.300 Winchester Magnum) or 3,230 (.300 Weatherby). The .30-06 does not make the .308 useless and, similarly, the .300 H&H did not kill the .30-06. Each has its uses and particular applications.

In the case of the .300 Holland & Holland, its case capacity allows the handloader to load heavier bullets than the .30-06 with useful increases in velocity, while never encountering pressure problems or sticky cases no matter how hot it gets. The reliability of feeding and extraction is a big selling point for hunting in the tropics.

Ken Waters, who wrote for Handloader for many years and originated the “Pet Loads” column, wrote that the .300 H&H was his favorite cartridge, not least because it was shaped like an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Waters covered the cartridge in 1967 and again in 1984. He owned two rifles – a Browning High Power made by FN and a custom-built Holland & Holland, which was a gift. When he was told the H&H rifle would be made to his specifications, he chose to have it chambered for the .300 H&H. What’s more, not wanting to mar the DWM action by mounting a scope, he specified an aperture sight on the cocking piece.

Ken Waters was a romantic, but he was also a realist and almost painfully honest. He never said a cartridge could do anything that could not be proven. Here’s what he wrote about the .300 H&H in 1967: “(It) has always seemed to me very close to an ideal all-around cartridge, possessing all the necessary ingredients of fine accuracy, flat trajectory, woodchuck-to-brown-bear power, deep penetration or fast expansion as desired and readily controllable by bullet selection, tolerable recoil and easy reloadability.”

Seventeen years later, he added that “on a basis of ratio of powder charge to velocity, the .300 H&H is the most efficient of all the .300 magnums.” This admittedly arcane fact is echoed by more than one loading manual.

Finally, Waters noted that he had compared ballistic results of the .300 H&H with his own loads in both the .308 Norma and .300 Winchester Magnums – chronograph results from actual rifle barrels rather than laboratory test barrels. Maximum velocities with the Norma cartridge ranged from 27 to 72 fps faster than the H&H, and 37 to 79 fps greater with the Winchester. The only big .300 he tested that delivered a significant velocity increase was the .300 Weatherby.

The test rifle I used here is a Winchester Model 70 made in the early 1950s – in the opinion of many hunters, the absolute sweet spot of Model 70 production. No Monte Carlo comb, no white-line spacers. A 26-inch barrel and a factory trigger that is crisp and not too heavy (4.5 pounds).

Originally, I intended to test it the way Waters did with his Holland & Holland rifle – open sights only – but found the (non-original) iron sights shot about 18 inches high at 50 yards and that was at the lowest setting. Fortunately, it had been drilled and tapped, so I fitted a Zeiss Terra 3-9x 42mm scope in S&K mounts and that solved the problem.

As with most cartridges, handloading allows a shooter to increase or decrease the power, depending on what is needed and also to tailor loads for maximum accuracy. I was hoping to try some of the new powders on the market to see if I could get any marked improvement anywhere.

The immediate problem I encountered with the .300 H&H is simple lack of data. Shooters World has no data for its powders with the cartridge – but then, why would it, since no one chambers it now and it’s hard enough keeping up with the new hotshot cartridges that appear about once a week.

Hodgdon, including IMR and Winchester, had lots of data for many powders in many bullet weights, but only the old established powders. Again, why do the necessary testing with new powders for a cartridge that is old by any standard?

The powder that really set the .300 H&H apart in the 1940s was IMR-4350, the original “magnum” powder that stoked heavy bullets in big cases and changed the game entirely. It was introduced in 1940, and John Wooters reported in Handloader No. 27 (September 1970) that DuPont developed it specifically for the .300 H&H. Good as it was, and is, the arrival of Hodgdon’s H-4831 in 1949 took it the final step. Suddenly, every magnum cartridge was capable of clearing tall buildings at a single bound.

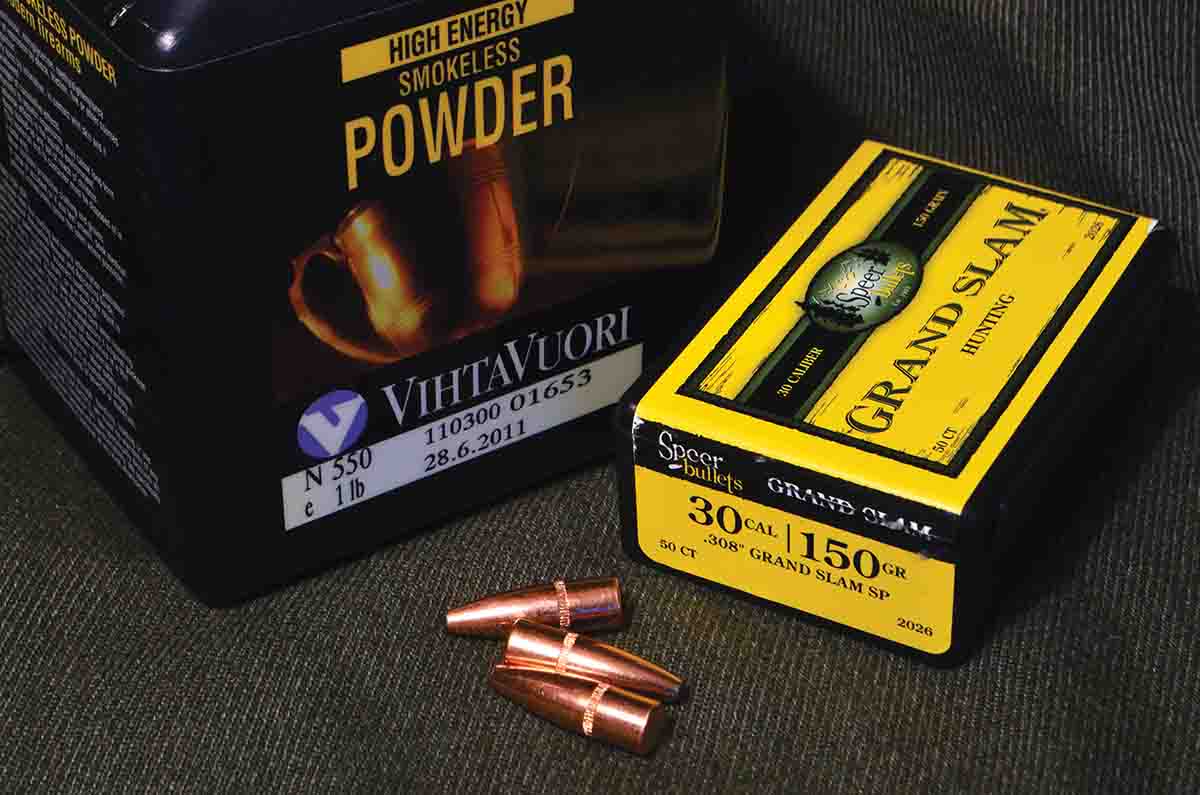

Alliant’s Reloder 22 is also good, as is Vihtavuori N550, among others. Essentially, any of the 4350s, 4831s or slower Reloder numbers is a good candidate.

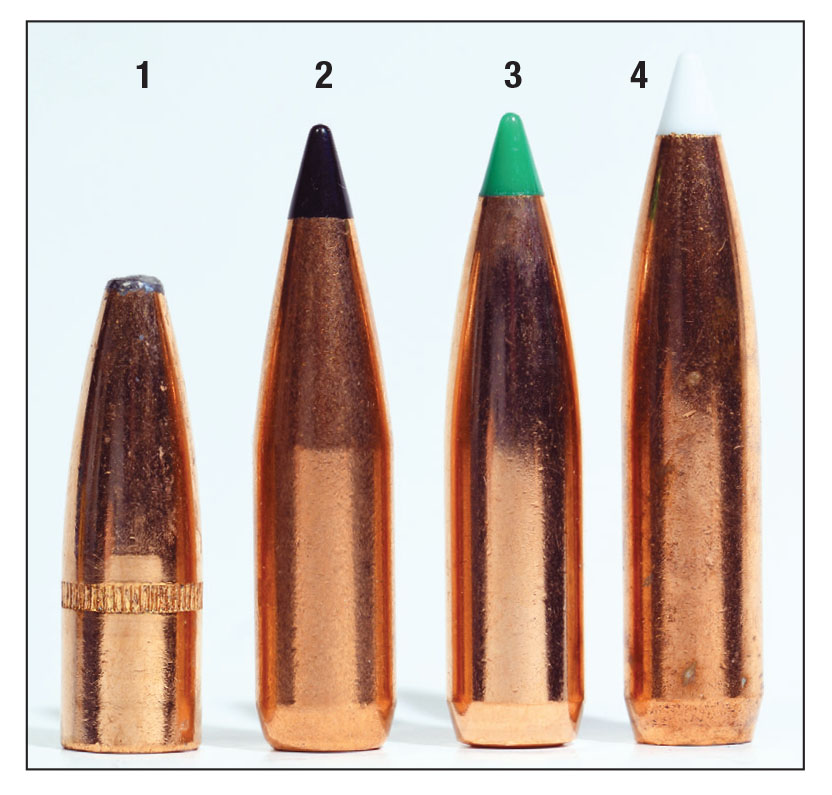

Originally, the .300 H&H was offered in bullet weights of 150, 180 and 220 grains, and I’ve seen load data for bullets as light as 100 grains and as heavy as 250 grains. For general big-game hunting, it seems to me the cartridge and its substantial powder capacity are best utilized with 165-grain and 200-grain bullets.

One can argue it either way but the clincher, to me, is the fact that some of the best premium bullets available today are those weights, made with the .300 magnums in mind, and offering the most aerodynamic shape combined with the best terminal performance. This is a general statement (I know) and there are exceptions (I know) but if it were me and I had to use a .300 H&H for everything in North America, I would load with those two weights and never look back.

An early criticism of cartridges that headspace on the belt is that they expand to fill the chamber, then, when full-length resized, stretch again, eventually leading to head separations. To prevent this, Waters recommended neck-sizing only. That’s good advice, and works perfectly well, provided (!) the cases are used in the same rifle and maximum loads are avoided. Even with maximum loads, however, the cartridge’s taper discourages case sticking.

Waters also found the best accuracy with loads in the middle range – neither starting loads nor maximum. Another loading tip: When they say the maximum overall length is 3.6 inches, they don’t mean 3.601. The magazine box in my Model 70 objected to cartridges even a hair over 3.6 inches.

I am not a great believer in stressing rifles, especially older ones, unnecessarily. When I can get a 200-grain bullet to depart the muzzle at 2,940 fps, I feel no overwhelming compulsion to push it up over 3,000. The rifle likes it, and so does my shoulder.

The loads shown here were deliberately chosen to be halfway between the recommended starting load and maximum. All .300 magnums do better with 26-inch barrels, especially with slower powders, and this one is no exception. To take the 200-grain results as an example, I got the load from the Speer Handloading Manual Number 15, which lists 66 grains as maximum. Speer recorded a muzzle velocity of 2,839 fps from a 24-inch barrel. With a 26-inch barrel, I not only got 100 fps more velocity, but did it with a load that was two grains lighter.

The Model 70 weighs, with scope, 9 pounds, 1 ounce. With its long barrel and replacement recoil pad (done before I got it), it is quite comfortable to shoot. The 150-grain load, especially, would be great for deer.

As for its accuracy, the worst five-shot group was 2.4 inches, the best was 1.3, and the average for the four was 1.97. I’d take the 150-grain load hunting anytime. In 1952, accuracy like this would be considered gilt-edged. Even in the late 1980s, Weatherby’s groundbreaking accuracy guarantee was 1.5 inches, and that for only three shots, and it was considered pretty daring.

Speaking of Weatherby, an illuminating anecdote: In 1975, I bought my first serious rifle, a Mark V in .300 Weatherby Magnum with a 24-inch barrel. With that rifle, I shot two caribou, an Alaskan brown bear and a British Columbia (Canada) moose. Around 1990, I got my first chronograph, and what did I find? My pet 200-grain load with a Trophy Bonded Bear Claw achieved only 2,808 fps. Another load averaged around 2,740 fps.

Accuracy was excellent, and my shot on the moose was one of the most spectacular of my life, but in spite of its deafening muzzle blast and memorable recoil, it would not have matched the .300 H&H we have been discussing here. That tells you something.

.jpg)