Lyman: 140 Years of History

"Ideal" Handloading and Shooting Gear

feature By: John Barsness | August, 18

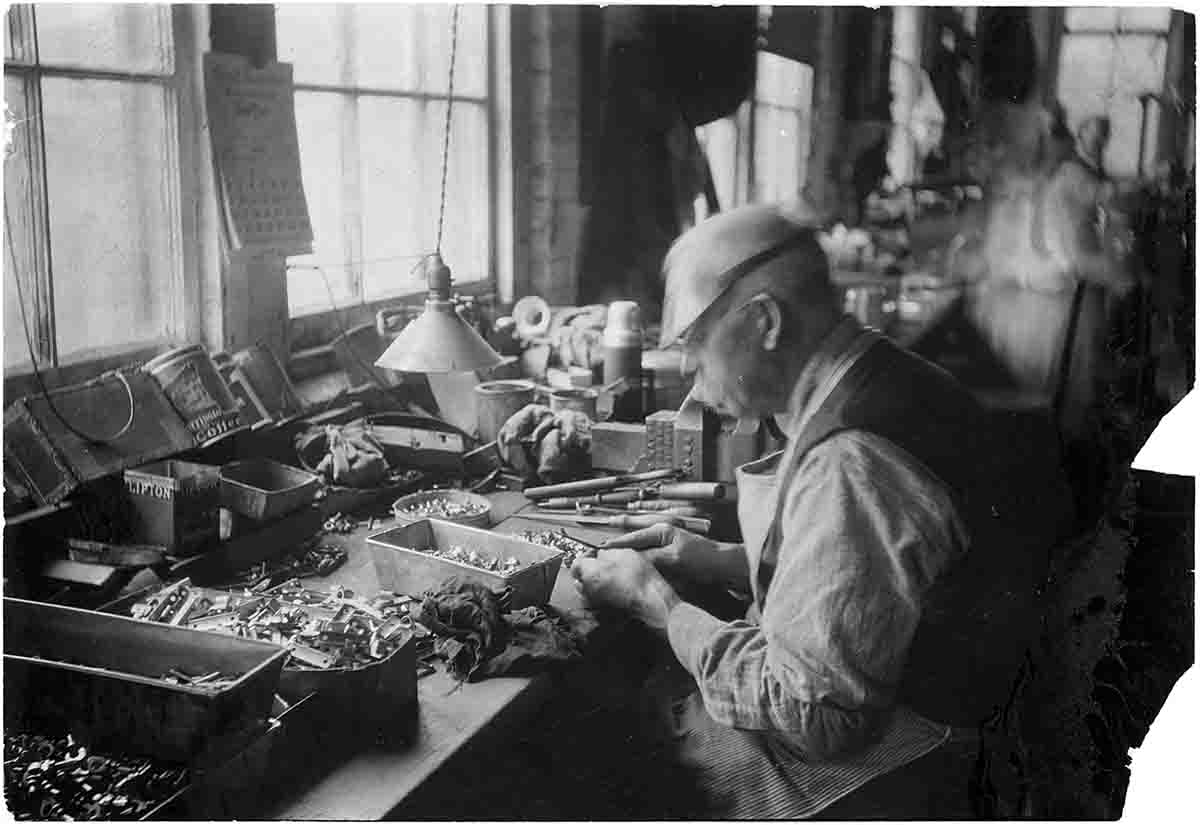

William Lyman had apparently been inventive even as a young boy, using his corner of the factory to experiment with various ideas. He enjoyed boating, spending plenty of time on nearby Besseck Lake, and in 1875 was issued U.S. Patent No. 169,277 for oars that allowed a boater to row in the direction he faced instead of the conventional backward position. He also liked to hunt but was dissatisfied with available sights because they made aiming difficult in dim light. The “No. 1” had a small disc and relatively large aperture, allowing more light to reach a hunter’s eye, and it became so successful that William set up his own factory in a building in Middlefield in 1880, patenting a total of 17 sights before passing away from pneumonia in 1896.

The Lyman family continued to operate the growing factory, and employee James Windridge designed many more successful Lyman sights, including several variations on the Lyman No. 1 and the famous Model 48 receiver sight. Eventually the Lymans decided

Ideal Manufacturing was formed in 1884 by John Barlow, a former Winchester employee who had designed many of the handloading tools for the company’s rifles. Winchester’s factory was in New Haven, Connecticut, 20 miles from

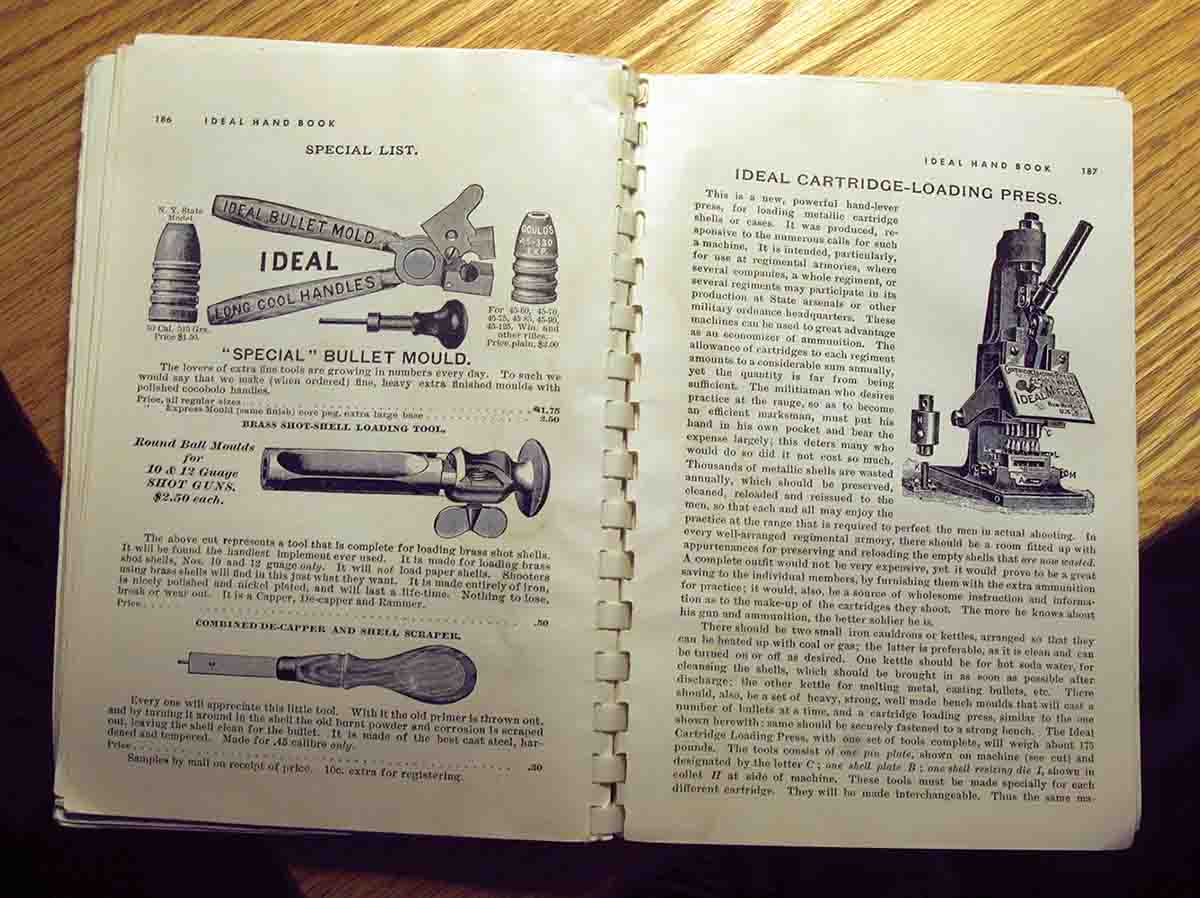

His first tool was an improved “nutcracker,” a hand tool resembling complex pliers that cast bullets, reprimed brass and crimp-seated the bullets for a specific handgun or rifle cartridge. Naturally, Barlow named it the Ideal No. 1 and eventually produced 10 variations for cartridges from .22 to .50 caliber. Additional features included decapping, bullet sizing and case neck sizing.

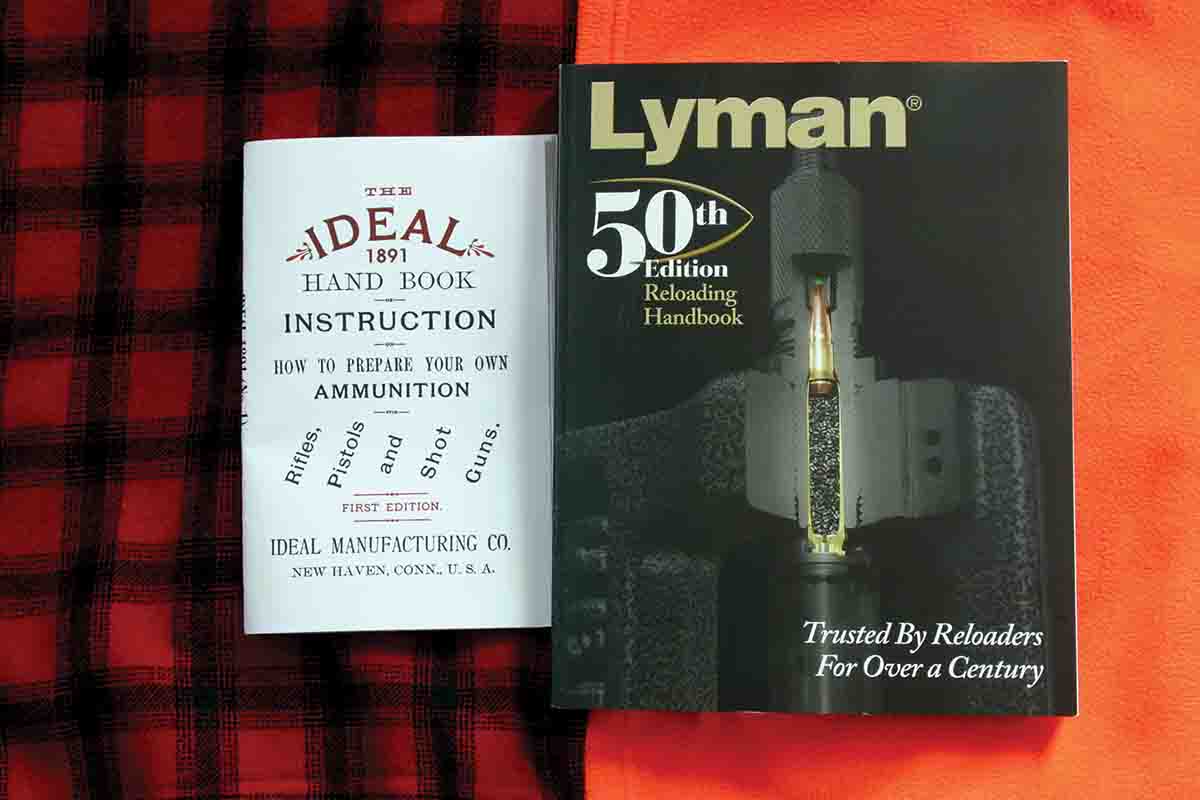

Ideal also made bullet moulds, including special orders, and in 1891 published the first American reloading manual, The Ideal Hand Book of Instruction on How to Prepare Your Own Ammunition. In it were step-by-step instructions for loading techniques plus a catalog of Ideal tools. Barlow apparently developed a close relationship with Marlin after leaving Winchester; the interior of the back cover was an advertisement for Marlin Fire Arms Company’s Model

John Barlow was an interesting writer with a sense of humor, and the old Ideal handbooks are a hoot compared to most modern loading manuals. My copy of the 1891 version was one of thousands of shooting-related reprints from Cornell Publications (P.O. Box 214, Brighton, MI 48116, cornellpubs.com) and contained a page of “Poetical Sayings,” including the word “ideal,” from various sources. Here are some samples: “The ideal is the flower-garden of the mind, and very apt to run to weeds, unless carefully attended to.” – Margaret Oliphant [Scottish novelist]; “The situation that has not its duty, its ideal, was never yet occupied by man.” – Carlyle [Thomas Carlyle, Scottish essayist and philosopher] “All sportsmen should carry an ‘Ideal’ in their kit.” – J.H. Barlow [owner of Ideal Manufacturing Company].

The loading manual continued to appear under the Ideal name, though over the decades the Lyman name became more prominent. The second loading manual I ever purchased, using paper-route money, was Lyman Ideal Handbook No. 42. I had recently purchased my first centerfire rifle (or rather my father had, with my

Along the way other old Ideal and Lyman manuals were added. The oldest is Ideal Hand Book Number 38 with “The Lyman Gun Sight Company Corp.” printed in small letters across the bottom of the cover. The next issue, No. 39, however, has Lyman printed across the Ideal name on the cover – but the last 59 pages, after the Lyman catalog section, are a partial reprint of one of an early Ideal handbook, with a stern warning from Lyman: “Please DO NOT ORDER from this section, items described are for GENERAL INTEREST, only.”

Two of Lyman’s recent books should be particularly appealing to many twenty-first-century handloaders. Lyman’s AR Reloading Handbook appeared in 2014 and not only contains data for a dozen cartridges from the .204 Ruger to .50 Beowulf, but has chapters on related subjects such as suppressors and specific techniques for handloading AR rounds. Hot off the press in 2018 is Lyman’s Long Range Precision Rifle Reloading Handbook containing long-range load data for 14 popular cartridges from the .223 Remington

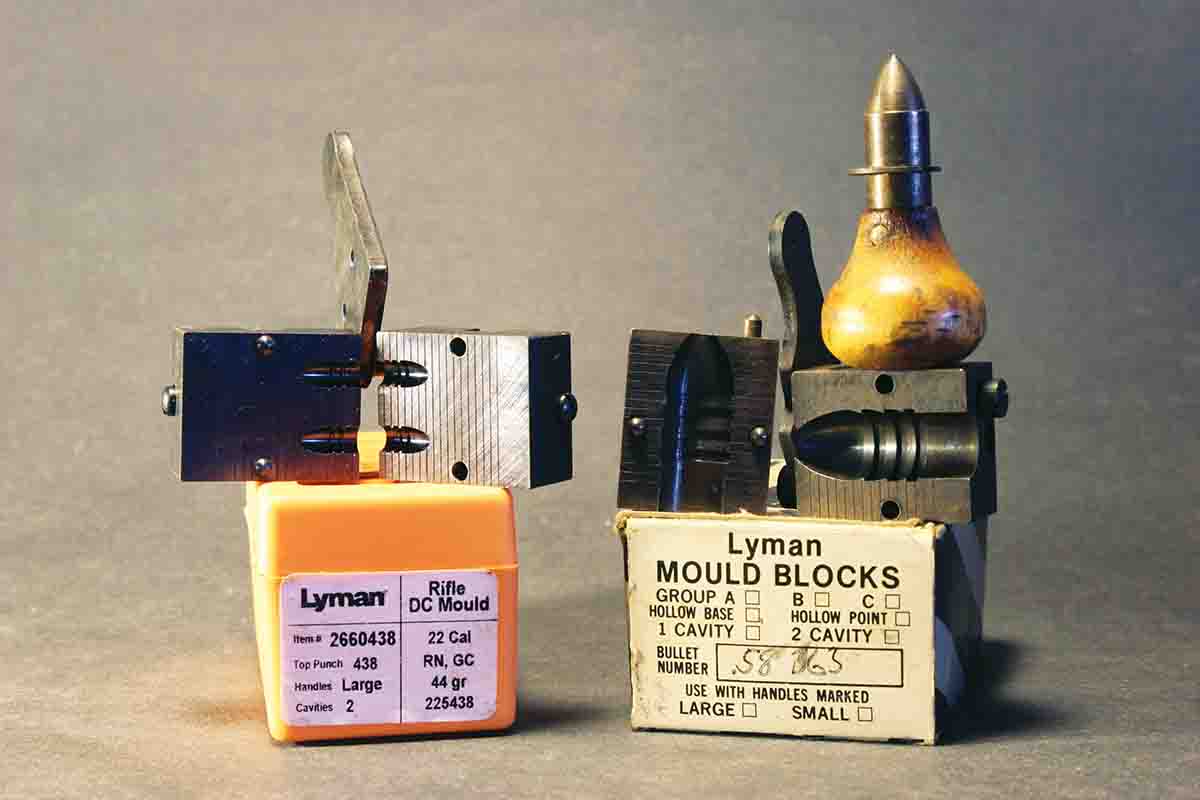

Lyman is very well known for its bullet moulds. I acquired my first in the mid-1970s, a No. 358156 with two cavities, which many handloaders consider the mould for the .38 Special and .357 Magnum, and it continues to cast fine bullets today. My latest (and smallest) is No. 225438 used in “Beating the Rimfire Shortage” in Handloader No. 290 (June 2014). I’d heard numerous tales about the difficulty of getting cast .22 bullets to shoot well, but the mould’s 43.5-grain bullets, as cast from wheelweights, grouped inside an inch at 50 yards from both a .22 Hornet and .223

Among the first loading tools Lyman modified after acquiring Ideal was the nutcracker series, renamed the Lyman 310. It’s still available for the .38 Special/.357 Magnum, .44-40 WCF, .44 Remington Magnum, .45 Colt, .30-30 Winchester, .38-55 and .45-70. The modern version includes a neck resizing and decapping die, primer seating chamber, neck expanding die, bullet seating die and case head adapter – but no bullet mould.

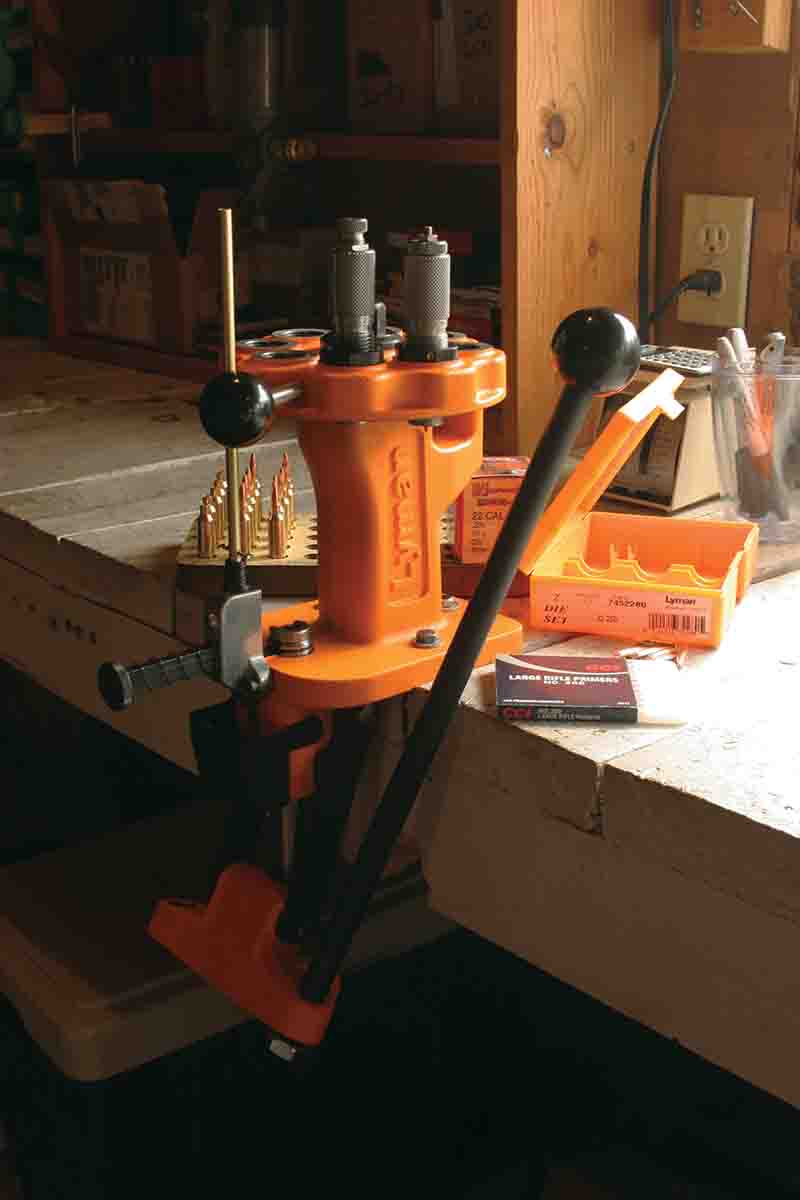

Lyman/Ideal has been offering bench-mounted presses and dies for a long time as well, as evidenced by the reprint of an old Ideal handbook in the back of Lyman Ideal Handbook No. 39. Among the most popular when I started handloading was the Spartan C-press, but the company also offered a variety of other presses, including shotshell loaders and a four-hole turret press, the Tru-Line Jr.

The most recent metallic press is another turret model, the Brass Smith All-American, with eight die holes, at least one more than any other available turret press. As anybody who uses turret presses knows, there’s a tendency to fill all the holes, then wish for just one more. The Lyman eight-hole press won’t cure the typical American wish for extra everything, but anything helps.

Unlike single-hole presses, turret presses present the possibility of the holes not being precisely like the others. Handloaders want a seating or sizing die to work the same way when screwed into any hole. I tested the Brass Smith All-American by loading ammunition for a Ruger American Rifle .22-250 Remington, a limited-run version with a 1:8 rifling twist offered by Whittaker Guns (6976 West Louisville Ln, Owensboro, KY 42301; whittakerguns.com). I filled my 2017 Montana pronghorn tag with the Ruger using a Hornady 70-grain GMX monolithic bullet and a maximum load of Hodgdon SUPERFORMANCE for around 3,400 fps. It worked fine at 350 yards on the biggest buck in the neighborhood, so I decided to load some more ammunition with the Lyman press because the 70-grain GMX is very uniform in length and ogive shape, so it would provide a good check of seating depth.

First, eight rounds were loaded with the seating die screwed into a different hole for each round. Their overall length varied .0015 inch, the same variation as the length of the bullets, and also varied .0015 inch when measured to a datum line scribed in the middle of the ogive.

Eight more rounds were then loaded, this time with the seating die left in the same hole. Their variation was basically the same, so yes, Lyman’s new turret press is very well made. It’s also pretty stout; in fact, our FedEx guy warned me the package was heavy when he handed it over.

Lyman also offers a complete line of other loading tools, including a case trimmer and case prep center, a case-cleaning tumbler and several ultrasonic brass cleaners. Ten different powder scales and measures are available, both electronic and manual, including the classic No. 55 powder measure. One of my measures is a No. 55 with the Homer Culver micrometer adjustment favored by benchrest shooters for decades, and it is often semi-copied by other manufacturers. Mine was a generous gift from Dr. Ken Oehler and is used often when making 6mm PPC ammunition for my benchrest rifle, or a bunch of precise prairie dog rounds.

Perhaps the best deal, however, is the Ideal (there’s that word again) Reloading Kit, including an Ideal C-press, powder measure and stand, Pocket Touch 1500 electronic scale, loading block, Care Prep Multi-Tool, E-ZEE Prime hand-priming tool, Quick Slick case lube and the Lyman Reloading Handbook, 50th Edition – all for $249.95. (Higher- priced kits are also available with the Victory O-press or eight-hole All-American, plus a larger selection of tools.)

Of course, Lyman isn’t just about handloading. The manufacturer also offers traditional muzzleloading and black-powder cartridge rifles, grips and other accessories for handguns and rifles, gun care products and yes, “iron” sights, including several tang-mounted models resembling the No. 1 that started the company 140 years ago.

Lyman long ago outgrew the original building and is now located a few miles away in Middletown. The original factory still stands, and in fact is registered with the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation. It looks very much like it did when the long sign across the front read “The Lyman Gun Sight Corp. Middlefield, Conn.” If you’re ever in the neighborhood, you might want to drive by 147 West Street and take a look at a piece of shooting history.