Old Bottle, New Wine

The .32-40 in the Modern World

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 18

As the name suggests, it was originally charged with 40 grains of Fg black powder and loaded with a 165-grain cast bullet. It eventually displaced the .38-55 as the favorite cartridge of Schützen competitors, combining excellent long-range accuracy with mild recoil. It was the favorite cartridge of barrel maker Harry Pope, who originated a variant called the .33-40, and the .32-40 was chambered in all the best single-shot rifles of the era.

With the coming of smokeless powder the .32-40 underwent something of a metamorphosis. Chambered in the Winchester 94, various Marlins and later the Savage 1899, it was loaded with smokeless powder and jacketed bullets and became a deer rifle. Although it is rarely billed as such, the .32-40 is the parent case for both the .30-30 and the later .32 Special. As hunting cartridges, both of those (as well as the comparable .303 Savage) shaded the .32-40 by a great deal. As the popularity of Schützen matches faded, so did the .32-40.

Unlike most other old black-powder cartridges, however, it managed to hang on in a variety of ways. After 1945 there was an influx of Martini-actioned cadet rifles from Australia, originally chambered for the .310 Cadet. For convenience, many of these were rechambered to .32-40, which has essentially the same bore diameter. It is common to find these still marked as .310 Cadet, so one needs to be cautious. Then, in

If new brass proves impossible to find (small makers usually produce limited runs, and shelves may be temporarily bare) it is possible to size down .38-55 brass to fit. Although the heads are the same on the .30-30 and .32 Special, those cases are shorter (2.03 compared to 2.13 inches) than the .32-40. One could slim down .32 Special brass, but the case would have less capacity, and particular attention would need to be paid to overall length if it’s worked through a lever action.

The bore diameter of the .32-40 is most commonly listed as .319 inch compared to later .32s that measure .321. Bullets listed as “8mm” also offer potential for the .32-40 since they are found in every diameter from .316 to .328. Many are in spitzer form, but there are also a few roundnose bullets. In a way, there is an embarassment of riches when it comes to projectiles, but a handloader needs to be cautious because of diameter and cannelure position.

Reloading the .32-40 presents a few peculiar problems, but it also offers the opportunity to do some interesting old-time things that are rarely seen today. Of course, if you have a Winchester ’94 .32-40 and want to hunt deer, it can be reloaded like any other rimmed cartridge, although suitable bullets and powder may not come easily to hand. If a rifle is intended for offhand target shooting, however, and you want to load just for that, you will need different bullets, probably a different powder and a completely different approach.

Early data does not differentiate among different makes of such powders as 4198 and 4895, so it is wise to check the publishing dates to determine which one they are referring to. Hodgdon-4895 predates the IMR product, so if you just see “4895,” you can assume it’s Hodgdon’s; the reverse is true for 4198.

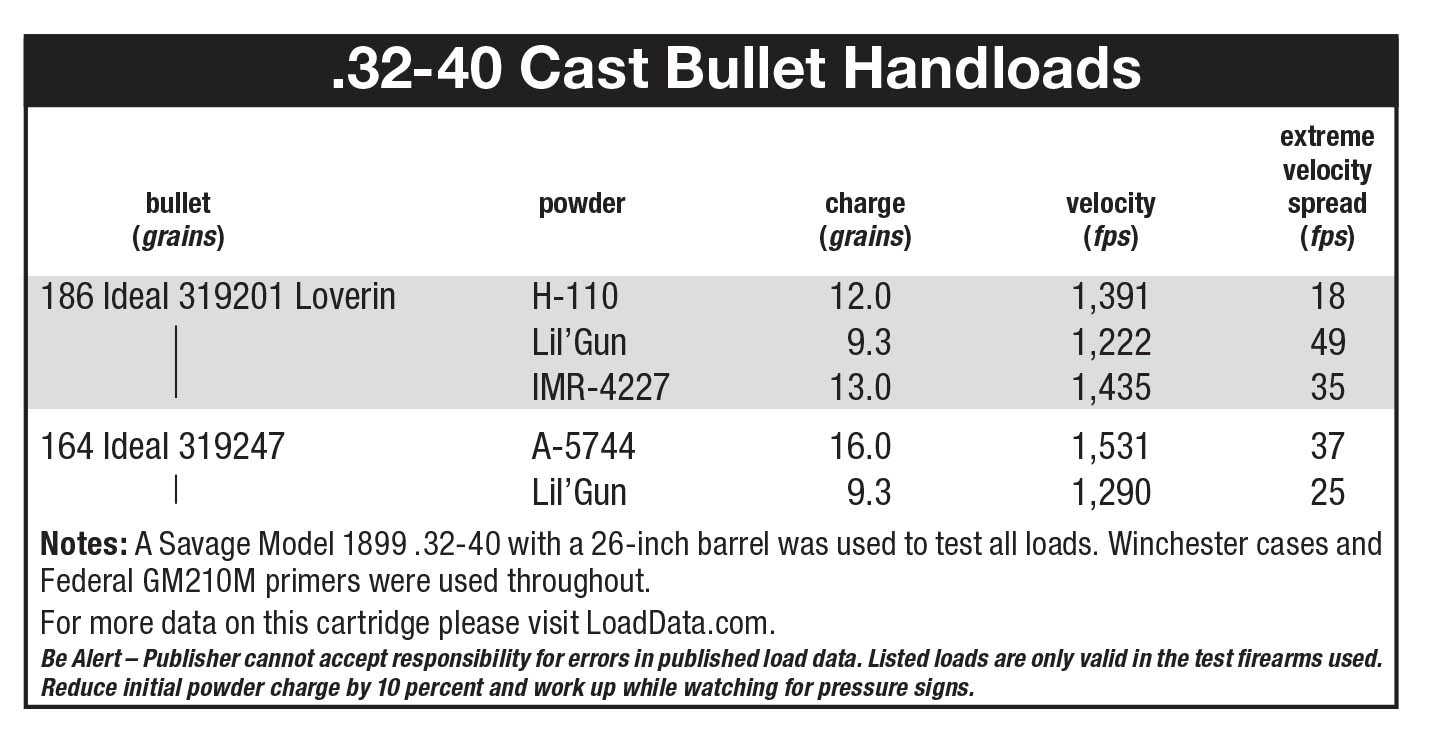

Finally, Hodgdon’s rifle data website today gives loads for bullets weighing from 196 to 204 grains, and suggests H-110, H-4227, Lil’Gun and Trail Boss. Of these, H-4227 is no longer available. I substituted IMR-4227, which is so close to H-4227 as to be interchangeable, although Hodgdon does not come out and say so. Most burn rate charts indicated that H-4227 is ever so slightly slower, but Speer’s Manual for Reloading Ammunition Number 6 (1964) gives loads for both powders with the .22 Hornet, and they are identical from starting loads to maximum, with virtually identical velocities. Since IMR-4227 was one of two powders (the other being Hercules, now Alliant 2400) developed specifically for the Hornet, that’s good enough for me – especially since, with the .32-40, we are dealing with mild loads anyway.

As can be seen, while there is certainly no shortage of data, finding it can involve wandering used bookstores looking for old loading manuals, and then following that up with a search for discontinued powders.

The bullet situation is not much different. At various times, according to Lyman’s Cast Bullet Handbook, 21 different moulds were available in 319xxx or 321xxx, any of which could be used in the .32-40 if correctly sized.

Anyone with a .32-40 of any description would be well-advised to slug the barrel before doing anything. Different manuals advise sizing bullets to either .319 or .321, and while opinions differ, most shooters size their bullets to be two or three thousandths larger than groove diameter. This is a matter of trial and error for individual rifles, to see what works and what doesn’t. Another point raised by Ken Waters is the relative strength of various actions; the Winchester 94 is strong, the Ballard is not. Before loading anything, it is essential to determine whether you have a rifle with a strong action or a weak one, and proceed accordingly.

I have two .32-40s, but they are so different their ammunition needs to be treated as separate cartridges. One is a Martini cadet rifle rechambered to .32-40; the other is a Savage 1899 built around 1916 as an offhand target rifle with a 26-inch octagonal barrel. My original intention with this article was to include both, but it became a logistical labyrinth, with segregated brass and completely different bullets. Finally, I settled on the Savage with two bullet weights and using only modern powders, but loading the rifle as an offhand competitor might have done in 1916.

One method was to seat the bullet from the muzzle, ensuring exact alignment and a perfect base, with no fins thrown up by the rifling. A primed case charged with powder was then inserted from the breech to provide the power. Another approach was to seat the bullet in the rifling from the rear with a special seating tool and then chamber the case after it. Finally, the shooter could seat the bullet partially into the case, uncrimped and well out from maximum seating depth. Then, as the cartridge was chambered, the closing bolt would push the bullet up into the rifling, which in turn would seat the bullet farther into the case. This provided perfect, consistent alignment with bore, bullet, case and breech face all in firm contact. Some barrels were specially rifled with closely fitted leades to accommodate the second and third techniques.

Also, because smokeless powder did not completely fill the case, it was common to elevate the muzzle to ensure the powder was up against the primer, then gently lower it into shooting position. This gave consistent ignition.

With cast bullets, the case mouth must be belled slightly before seating the bullet. To use the method described above, seat the bullet just far enough in that it is held solidly. Then, in the crimping die, straighten the bell very carefully so the case will fit into the chamber but with the mouth not closed tightly around the bullet. This allows the bullet to slide in farther as the action is closed but without gouging. As the round is chambered, you feel the bullet come in contact with the rifling then seat more deeply as the action locks closed. Obviously, the rifle cannot be unloaded without running the risk of the bullet sticking in the rifling and scattering powder through the action – one more little wrinkle to shooting the .32-40.

With properly lubricated cast bullets, the ideal velocity is usually from 1,200 to 1,500 fps. Even with a 196-grain cast bullet, there is little recoil and remarkably little noise, which makes the .32-40 very pleasant to shoot.

Reloading the .32-40 is never a search for maximum power or high velocity; it just doesn’t lend itself to that. Turning a .32-40 into a deer rifle can be done, but it will never match the power of a .30-30, much less anything more modern.

To handloaders accustomed to buying off-the-shelf components and getting “precision everything” that goes together almost without thought, the .32-40 is undoubtedly a challenge. What makes it worthwhile is the opportunity to shoot some of the most interesting rifles ever made, and matching the load to the rifle is undoubtedly educational. If nothing else, it makes a handloader appreciate just how good we have it today, thanks largely to all those shooting pioneers of a century ago.