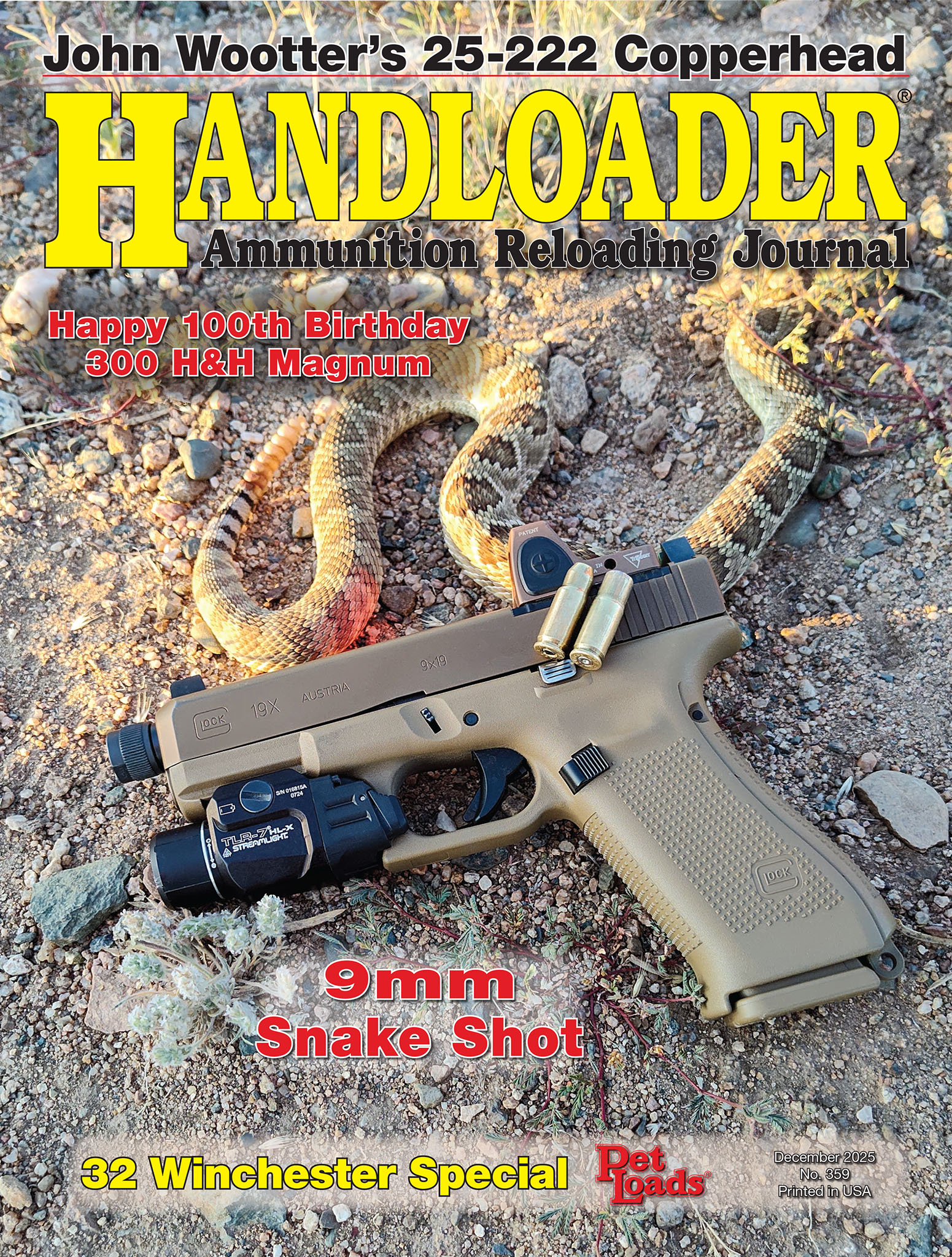

32 Winchester Special (Pet Loads)

Better than the 30-30?

other By: Brian Pearce | December, 25

The 32 Winchester Special (W.S.) was introduced in 1901 and first appeared in the 1902 Winchester catalog (although some sources suggest 1898, but this is not well supported). In glancing at the ballistics and comparing them to the 30-30 Winchester, most of today’s shooters will wonder why the 32 W.S. ever existed; after all, it only offers a very small ballistic advantage. However, at the time it was introduced, it definitely offered several advantages over its smaller 30 caliber brother, and explains why it remained popular for many years. It’s unknown how many rifles were made by Winchester, Marlin and others, but it was a very popular cartridge. I don’t know when the last rifles were produced, but Winchester and Marlin continued to offer lever-action rifles until long after World War II and into the 1970s, and Winchester produced special Model 94 Wrangler variations during the 1980s. Regardless, there are still many rifles in use, which warrants a “Pet Loads” feature article with modern components.

U.S. ammunition companies began implementing smokeless powders during the early 1890s in select U.S. cartridges. This signaled the change from black powder to smokeless powder in virtually all cartridges, although some took a while to make the transition. The first U.S. sporting smokeless rifle cartridge was the 30 WCF or 30-30, that debuted in 1895. While it was instantly popular due to the handy 1894 rifle and carbine, its comparatively high velocity and the U.S.’s destined love for thirty caliber cartridges, etc., the average cowboy, trapper or backwoodsman could not reload it due to smokeless powders not being available as a component, and neither were scales readily available to properly weigh charges. Basically, black powder cartridges were practical and alive and well in the 1890s! With nothing more than a tong tool, the case neck could be sized, a primer installed and the case filled with black powder and a cast bullet seated.

Winchester recognized a cartridge void in their offerings and decided to create the 32 Winchester Special specifically for the Model 1894. An excellent explanation of the 32 W.S. appears in the 1902 Winchester catalog, which states: “The .32 Winchester Special Cartridge, which we have just perfected, is offered to meet the demand of many sportsmen, for a smokeless powder cartridge of larger caliber than the 30 Winchester (30-30) and not yet so powerful as the .30 U.S. Army (30-40 Krag), which could be reloaded with black powder and give satisfactory results. The .32 Winchester Special Cartridge meets all of these requirements. Loaded with smokeless powder and a 165-gr. Bullet, it has a muzzle velocity of 2,057 feet per second (fps). With a charge of 40 grs. of black powder, the 32 Winchester Special develops a velocity of 1,385 fps, which makes it a powerful black powder cartridge.”

The 32 W.S. was based on a necked-up 30-30 case to accept .321-inch bullets. Naturally, when a case is necked up, pressures drop for a couple of reasons when the same weight bullets are used. Period ballistics of the 32 W.S. gave it a distinct ballistic advantage over period 30-30 ballistics (that were notably lower at that time when compared to today’s factory loads). As indicated, the 32 W.S. pushed a 165-grain bullet at 2,057 fps, and when compared to the 30-30, which listed a 160-grain at 1,885 fps.

The 32 W.S.’s power advantage was welcomed by hunters, but as indicated in 1902 by Winchester, there was another distinct advantage. Winchester used a 1:12 inch barrel twist for the 30-30, while Marlin used a 1:10 twist that were less than ideal for black powder loads. This brings us to the black powder 32-40 Winchester cartridge that was modest in power, but had proved highly accurate among match shooters. Even with the superior “hunting” and high velocity ballistics of the 30-30, the 32-40 was more accurate and continued to dominate on target ranges. In creating the 32 W.S., Winchester used the same 1:16 barrel that was used with the 32-40. Accuracy was very good, but cowboys and backwoodsman could also load the 32 W.S. with black powder and cast bullets with outstanding results, the same as the 32-40. Along with factory-loaded smokeless powder loads that offered greater power than the 30-30, this was a significant advantage, and many savvy riflemen chose the 32 W.S. over the hugely popular 30-30.

Some critics of the 32 W.S. state that its accuracy was substandard. There is some truth to this claim, unjustly, I might add, and it needs some explanation. The standard barrel groove diameter was .321 inch plus or minus, and the standard jacketed bullet diameter was the same .321 inch. For unknown reasons, roughly 100 years ago, Winchester began using .318-inch bullets in their factory ammunition, which did nothing for accuracy when fired in the .321-inch barrel. How long they did this is unknown to this writer, but in pulling and measuring bullets from Winchester ammunition made shortly after World War II, they are the correct size at .321 inch, and they shoot well. All current factory loads from Federal, Hornady, Remington and Winchester measure .321 inch, and accuracy is good. In short, there are no accuracy concerns with the 32 W.S. using correct components.

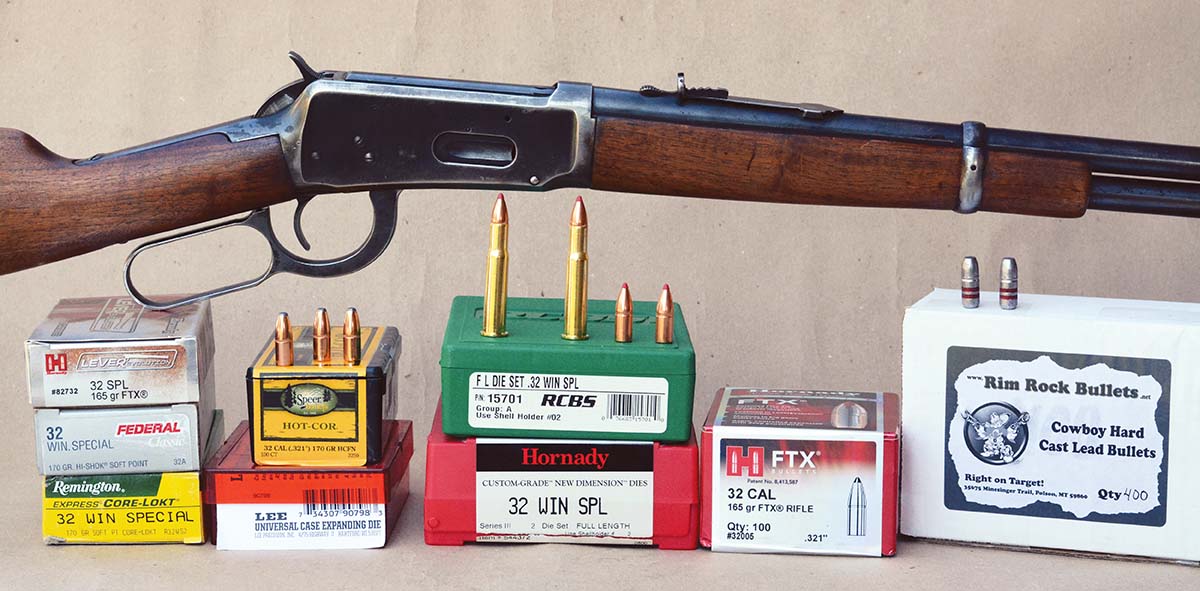

Eventually, Winchester began loading the 30-30 to higher velocities that closed the ballistic gap between it and the 32 W.S.. However, the latter has always been more powerful. Today’s factory loads from Federal, Remington and Winchester list a 170-grain bullet at 2,250 fps, but in testing those loads in the Winchester Carbine with a 20-inch barrel, actual velocities clocked between 2,100 and 2,150 fps. Hornady has returned to the original bullet weight of 165-grains that features the FTX (rubber-tipped spitzer bullet) at a listed velocity of 2,410 fps, but clocked from the test rifle at 2,274 fps. The ballistics of the above factory loads were easily duplicated or exceeded through handloading.

I generally avoid cartridge comparisons, but it seems relevant today. The 30-30 when fired from a 20-inch barrel falls significantly short of the listed velocities of 2,390 fps and 2200 fps with 150- and 170-grain bullets, respectively (which are velocities derived from 24-inch test barrels). I have tested virtually all 30-30 factory loads, and 150-grain bullet weights average around 2,200 fps, while the 170-grain loads clock around 2,000 fps average. From the 20-inch barrel of the 32 W.S., it was easy to push 150-grain bullets over 2,400 fps and 170-grain bullets at 2,200 to 2,300 fps. Clearly, the 32 still holds a significant advantage over its smaller caliber brother.

For today’s “Pet Loads” data, a Winchester Model 94 carbine was used, which was made during World War II. This flat-band edition, in which the front barrel/magazine tube is not contoured to save machining time and costs during the war, has been in my personal collection for many decades and has always been a reliable shooting rifle. However, it is fitted with a factory-installed semi-Buckhorn rear sight and bead front, which is less than ideal for accuracy testing. The receiver is not drilled and tapped to accept an aperture sight. The point being that I was somewhat stuck with the factory open sights. As a result, accuracy testing was done at 50 yards, wherein a respectable sight picture was easy to maintain.

It should be noted that many old guns have been shot extensively. This can result in heavily worn bores that may not shoot particularly well, but can also result in guns, especially leverguns such as the Winchester Model 1894/94 and 64, that develop excess headspace. Heavily worn Marlin rifles such as the Models 1893/93, 36 and 336 are not exempt. If in question, heavily worn guns should be checked for correct headspace, etc.

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute (SAAMI) list a maximum average pressure of 38,000 copper units of pressure (CUP), but has now been updated using piezoelectric measurements at 42,000 pounds per square inch (psi). All of the accompanying data is within that limit.

A few years back, Starline Brass began offering the 32 W.S. as a component that was used exclusively in developing the accompanying data. These cases are strong, well-made and helped to make it relatively easy to handload the 32 W.S. For example, their rigid construction makes it much less likely to damage cases during bullet seating or while applying the crimp. Furthermore, they seem to be putting less pressure than in previous cases. They are available factory direct and are in stock.

While the crimp can be applied simultaneously with the bullet seating step, this only works if cases are perfectly uniform in length. Generally speaking, it is preferred to apply the roll crimp as a separate step. The crimp will play an important role in helping prevent bullets from deep seating when subjected to the pressure and recoil inertia associated with tubular magazines.

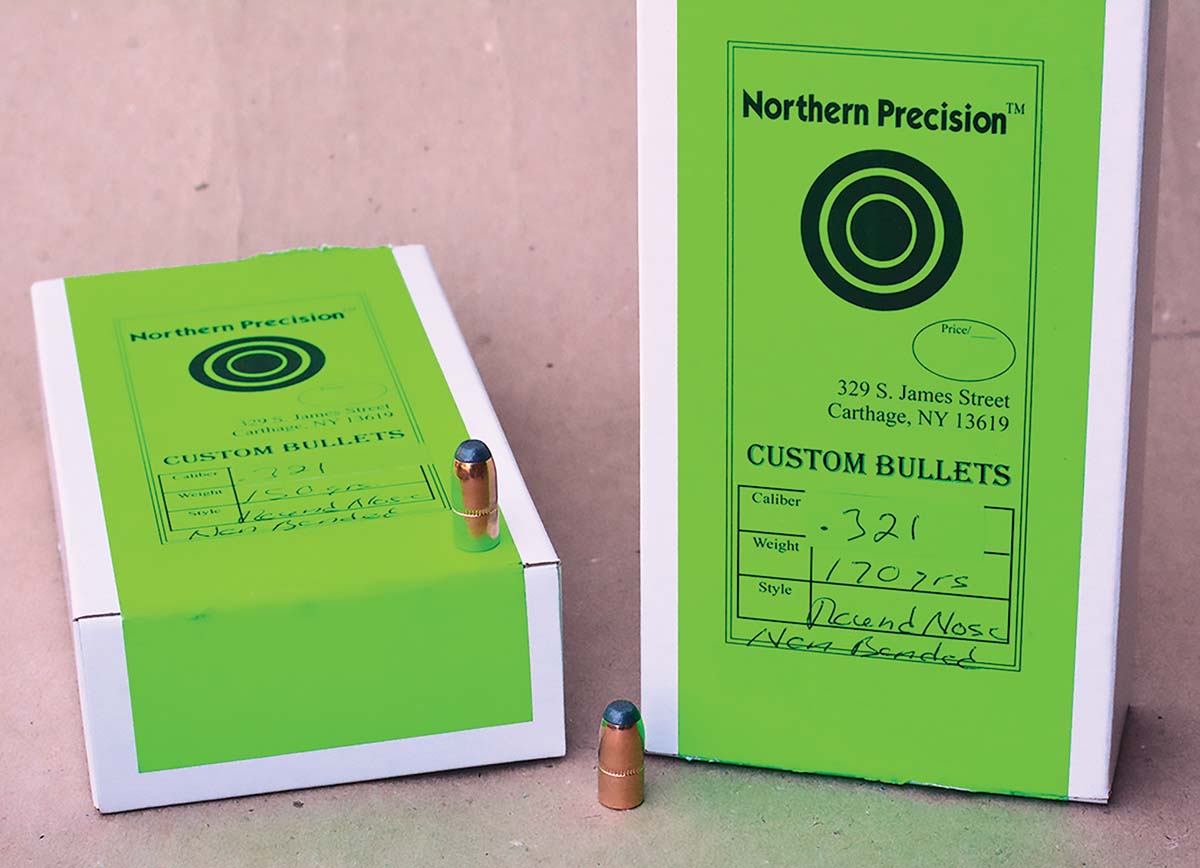

The selection of jacketed bullets in .321-inch diameter is reasonable. For many years, Hornady offered its traditional 170-grain cup-and-core Interlock flat-point bullet; however, that bullet has recently been discontinued in favor of the 165-grain FTX bullet, which is a very good alternative. While it is famous for being a spitzer profile with a rubber tip to allow its use in tubular magazines and offers a higher .310 ballistic coefficient (BC) – as opposed to their 170-grain bullet with a BC of .249 – in my opinion, its greatest attribute for deer hunters is its ultra-reliable controlled expansion. Reliable expansion has been a bit of a problem with some 170-grain cup-and-core bullets when distances exceed 100 yards or so. Certainly, the FTX’s higher BC and slightly higher velocities are an advantage, but that’s a relatively small advantage at typical distances that the game is hunted with the 32, which normally does not exceed 200 yards. And at that distance the FTX expands with a high reliably factor. Speer offers their 170-grain Hot Core Flat Nose, which is an excellent choice for hunting black bear and deer. Northern Precision Custom Bullets offers 150- and 170-grain Round Nose bullets (not bonded), but they each feature a distinctly flat point, making them suitable for tubular magazines. Northern Precision offers a bonded version of each.

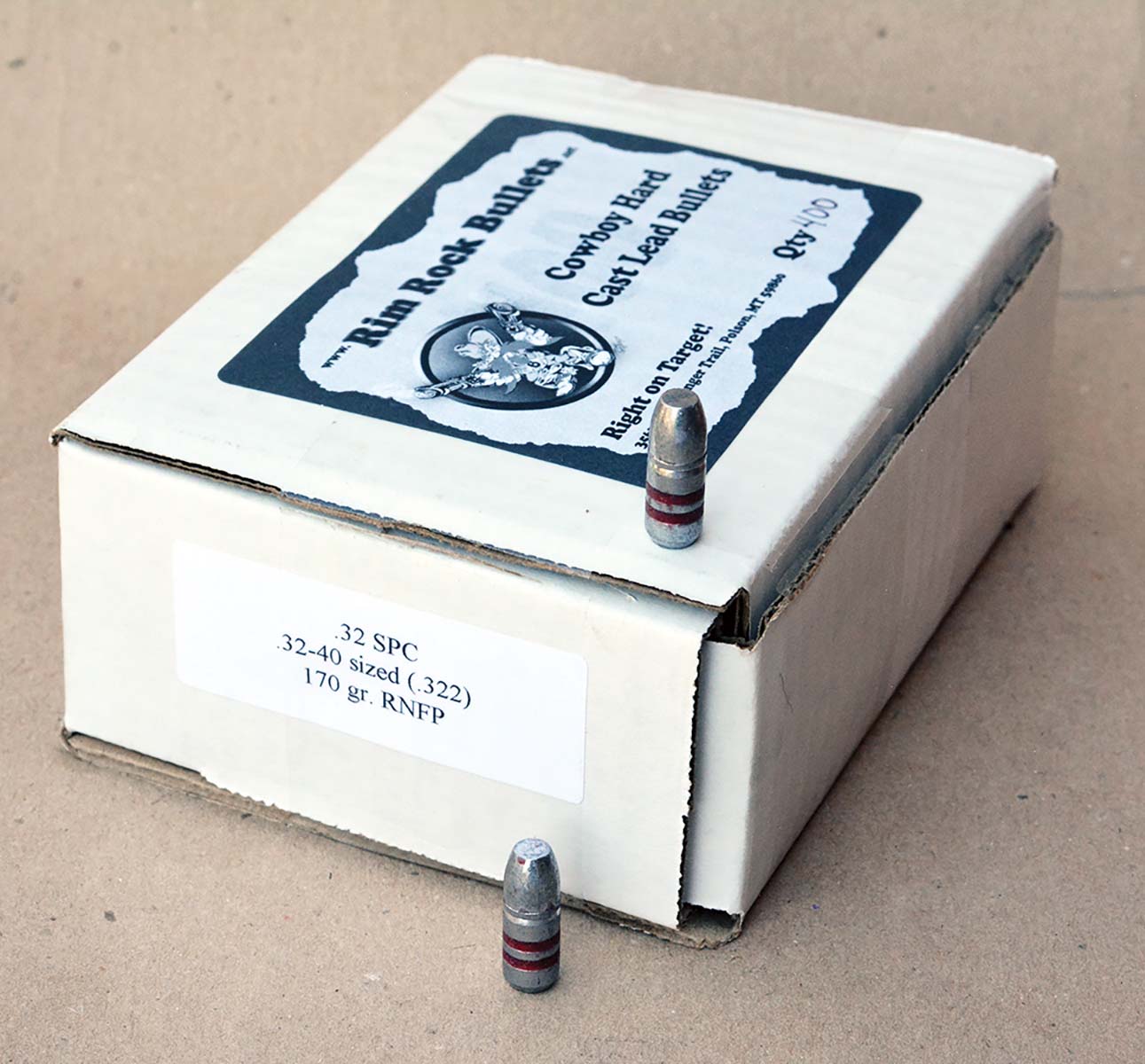

Exactly as it was originally designed, cast bullet loads were also developed that worked very well. Using Lyman mould 319247 that casts bullets at 166 grains, accuracy was very good at velocities as high as 1,700 to 1,800 fps using both Hodgdon H-4895 and IMR-3031 powders. For a low-cost plinking load, the Rim Rock 170-grain RNFP Cowboy bullet was used. Cowboy action shooters, plinkers and those seeking low-recoil loads can use 10.5 grains of Hodgdon Trail Boss powder for 1,340 fps.

Technically speaking, the 32 was a better cartridge than the 30-30; however, millions of shooters don’t agree with me! The 32 W.S. offered more power, greater versatility and probably greater overall accuracy and its extra velocity was a distinct advantage in obtaining reliable bullet expansion at normal distances where deer are hunted. On the other hand, 30 caliber cartridges were destined to become hugely popular in the U.S., and that is where the 30-30 had a birthright advantage. Regardless, updating the 32 W.S. with modern powders and components has been a fun project.

.jpg)

.jpg)