.38 Special (Pet Loads)

Standard Pressure Handloads

feature By: Brian Pearce | November, 22

The .38 Smith & Wesson Special, or more commonly known as .38 Special (not to be confused with the .38 Smith & Wesson), dates back to 1898 or 1899 (depending on source). In addition to having an unusually colorful history, it boasts of being our most popular centerfire revolver cartridge for the past 100 years. It has served in many military applications, is widely popular within law enforcement circles and has proven to be a top-notch target and field cartridge. While it was originally introduced in the Smith & Wesson K-frame revolver, known as .38 Military & Police (1st Model or Model of 1899 Army-Navy Revolver), it has been offered in a variety of double- and single-action revolvers, autoloading target pistols, rifles, derringers and single-shot pistols. Today, it remains widely popular in personal defense revolvers; however, recreation shooters, cowboy-action competitors and others still find it highly desirable.

The .38 Special was developed due to requests from the U.S. Government. At that time, the .38 Long Colt (with 150-grain bullet at around 730 feet per second) was the official U.S. military sidearm cartridge. But many experienced combat soldiers knew that it was rather weak and wanted greater power. But this issue was fully recognized during the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War wherein it proved unreliable in stopping the insurgent Philippine warriors and neither would it penetrate their shields. As a short-term solution, the proven Colt Single Action Army chambered in .45 Colt was pulled from government arsenals and issued to troops, which once again proved highly reliable in battle, but I digress. Government officials had already approached Smith & Wesson to develop a new revolver round that would be based on the .38 Long Colt, but with greater power. The .38 Special was the result, which featured a longer case at 1.155 inches (as opposed to the .38 Long Colt case at 1.025 inches) and held an additional 3 to 3.5 grains of black powder. It also featured a 158-grain bullet and produced around 100 to 150 fps greater velocity.

Space will not allow a complete discussion of the ballistics of the dozens of factory loads and U.S. military loads that have been, or are still being offered. A few noteworthy loads include early smokeless ammunition that featured a 158-grain lead roundnose bullet listed with a muzzle velocity of around 845 to 870 fps (depending on manufacturer, barrel length, etc.), which was a similar velocity to the original black powder load that contained the 21 to 21.5 grains. In spite of the stated velocity, their actual velocity was usually under 800 fps. Unfortunately, this load would become known as the “widow-maker” as it produced little shock and in general, lacked stopping power. Around 1920, at the request of law enforcement for a more effective load, the Western Cartridge Company developed a load containing a 200-grain lead roundnose bullet at around 671 to 730 fps and was known as .38 Super Police, while Remington-Peters soon offered a similar round. Reports suggest that the long bullet tumbled on impact that resulted in much greater shock. In 1930, Smith & Wesson introduced the fixed sight 38/44 Heavy Duty revolver and soon thereafter, the 38/44 Outdoorsman featuring adjustable sights. As the name indicated, they were built on the “44” or N-frame, and were capable of handling much heavier (greater pressure) loads than lighter frame sixguns. Soon various “.38 Special Hi-Speed” loads appeared that featured either metal piercing metal tip bullets that could penetrate car doors, radiators and the like, or lead bullets with a special copper-wash coating to control leading, all of which were designed with law enforcement in mind. However, these loads likewise gained acceptance with civilians wanting greater power from the .38 Special. At least three bullet weights were listed that included 110-, 150- and 158-grain weights. These guns and loads became the basis for further ballistic improvement that resulted in the .357 Magnum being developed in 1934 (a joint development between S&W and Winchester) and formally offered to the public in 1935.

Back to standard pressure .38 Special loads. Ammunition companies have been very responsive to offer trending ammunition. For example, many years ago when slow-fire bullseye-style target shooting was widely popular, wadcutter loads known as Match, Match Wadcutter, Police Match and such were developed that typically contained a 148-grain swaged-lead wadcutter bullet, usually with a hollow base, at between 690 to 770 fps. Even today, these loads remain popular offerings. In an effort to improve terminal performance, many companies began offering 158-grain “standard pressure” lead SWC-style bullets at 830 to 855 fps, which is a notable improvement over the traditional roundnose loads. Another popular approach to improve terminal performance is to offer lightweight jacketed expanding bullets that typically include 90-, 110-, 125- and 135-grain bullets, but at least one company offers a 158-grain jacketed bullet. As cowboy-action competition became popular, many began offering light recoiling cast or swaged lead bullets weighing 125-, 140- and 158-grains. The accompanying data will offer duplication loads for all of the above (except the 158-grain jacketed bullet), but will also include data to improve overall performance while staying within pressure guidelines.

Before proceeding, it is important to establish the differences between .38 Special and .38 Special +P loads. Referring back to the .38 Special Hi-Speed factory loads for the Smith & Wesson 38/44 Heavy Duty and 38/44 Outdoorsman revolvers, industry pressure guidelines, as well as suitable guns for these loads was sometimes rather vague and less than perfectly clear to the average handgunner. For example, loads for the 38/44 sixguns were not always headstamped for proper identification and resulted in their being fired in inappropriate guns. As a result, in 1974, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute established the .38 Special +P designation (indicating plus pressure), so that headstamps could be marked to better establish the two pressure levels associated with this cartridge. Industry +P pressure is currently established at 20,000 psi, which is not suitable for all .38 Special revolvers. Standard pressure .38 Special loads are currently established at 17,000 psi. All accompanying data is within that pressure limit, making it suitable for any gun in good, working condition. The list of guns that should only be fired with standard pressure loads is very lengthy, so it is suggested readers contact the manufacturer to determine suitability.

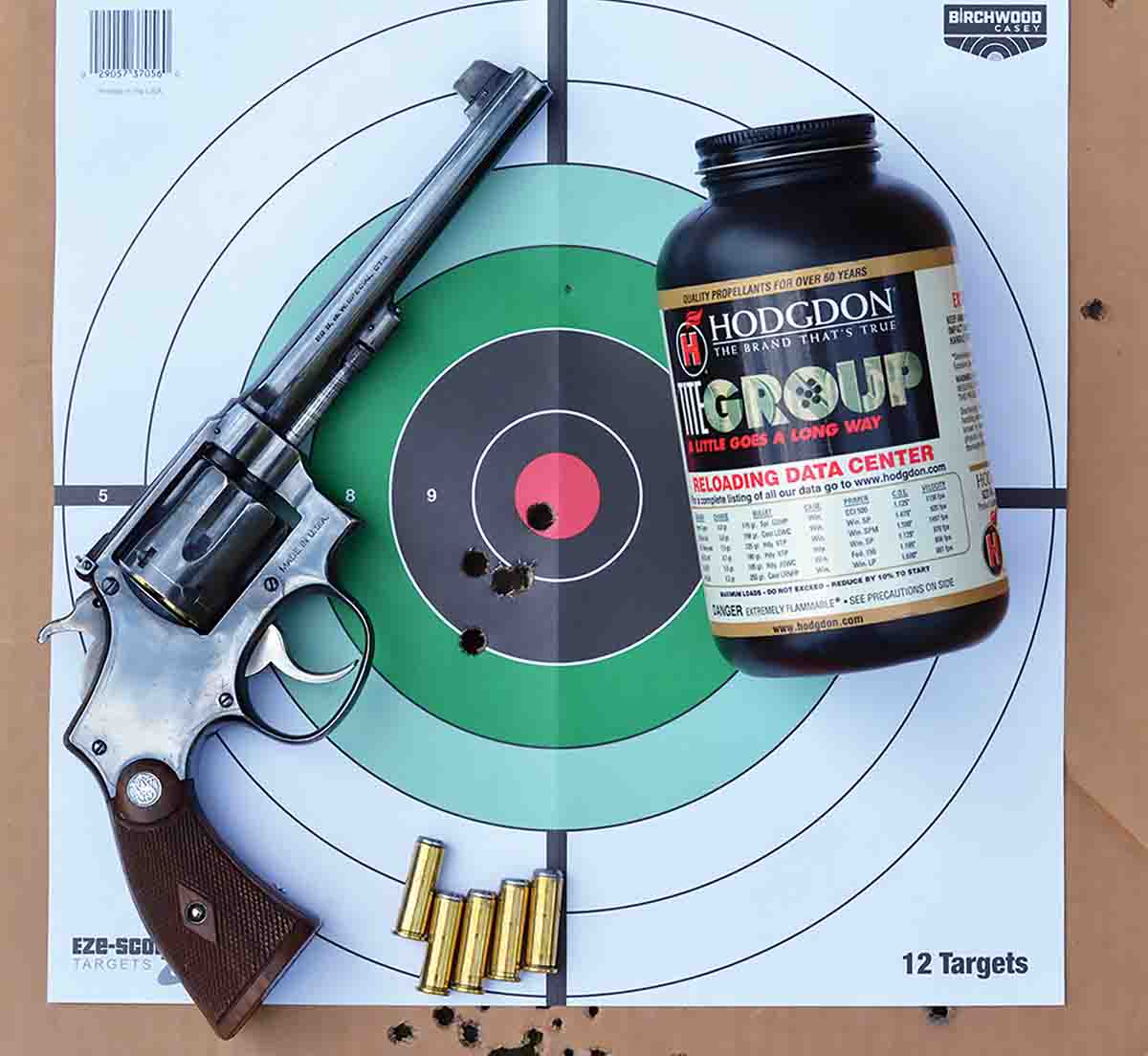

For today’s purposes, a Smith & Wesson pre-World War II Military & Police Model of 1905 Target Model with a 6-inch barrel was used to develop standard pressure data. For .38 Special +P data, please refer to “Pet Loads” in Handloader No. 304 (October - November 2016). Few guns can match the extreme quality of this sixgun that features a velvety-smooth, pre-war long action, crisp, single-action trigger pull, a good sight picture and a mirror-shinny bore that is excellent for use with cast bullet loads. This sixgun has proven accurate and is an appropriate, period-test vehicle.

I first began handloading the .38 Special in 1974, which at that time, included developing loads for a Smith & Wesson Chief Special, a K-38 Masterpiece and a Colt Single Action Army. I learned much about the cartridge and how to make my sixguns turn in top-notch target accuracy, along with useful field performance (mostly on small game and pests). Later, I used the great .38 in various revolver speed-shooting competitions. Even though big-bore sixguns are generally favored by this writer for daily use, the Special is certainly worthy of the unique title of being our most popular revolver cartridge.

Starline cases were used exclusively to develop the accompanying data. Incidentally, there are no other differences between Starline cases marked “.38 SPL” and “.38 SPL +P.” Rather the headstamp differences are only intended for load identification. It is noteworthy that there are great variances in case construction, materials, heat-treating methods, etc., even from the same manufacturer, but it is most prevalent in older cases. Generally, cases that are void of a cannelure(s) will offer longer case life, and tend to stretch less. Cases that can be full-length sized with very little effort, or seem very soft, are most prone to be the cause of poor ignition and can contribute to squib loads. These cases are best when used with deep-seating wadcutter-style bullets (as they limit powder space and aid with proper powder ignition) and that are usually loaded in conjunction with small charges of fast burning powders.

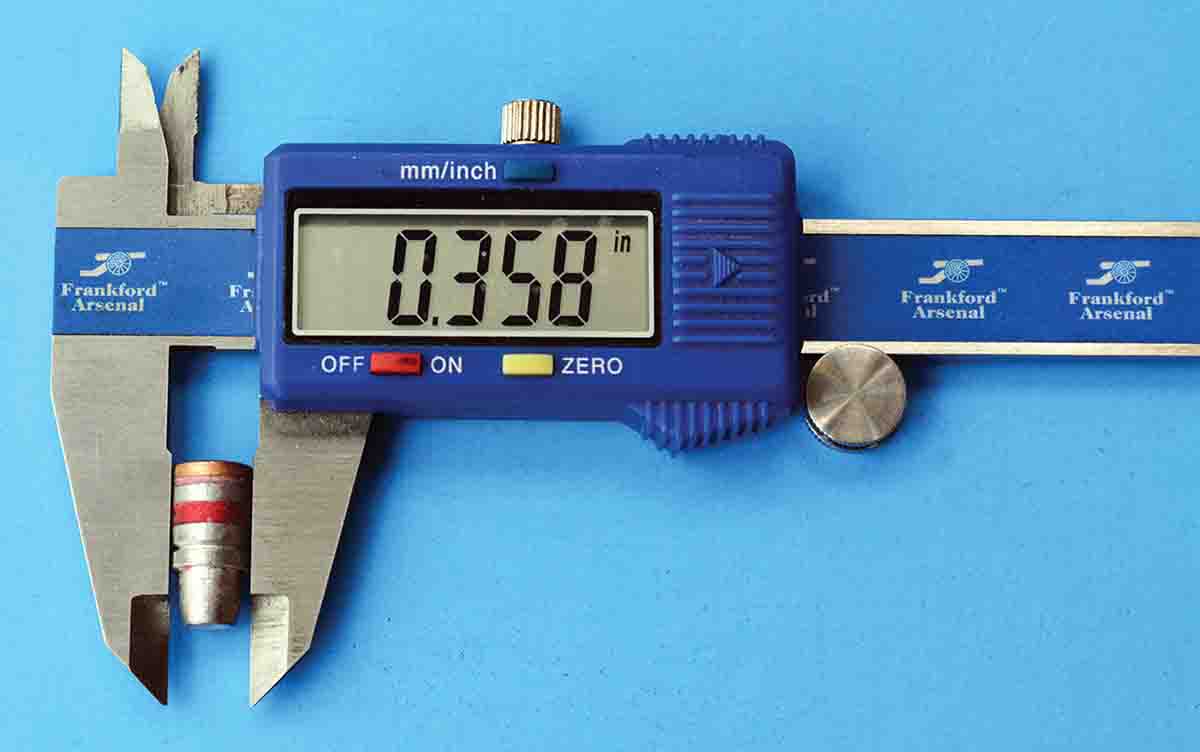

All cases were full-length sized using a Lyman carbide die. At this point, two sizes of expander balls were used to prepare cases for various loads. For loads containing comparatively soft, swaged lead bullets from Hornady and Speer, as well as Rim Rock Bullets soft-cast 158-grain SWC-HP with gas check, all sized at .358 inch, an expander ball measuring .356 inch was used. This helps prevent bullet deformation or their being swaged down as they are seated into the case, which generally improves accuracy. For hard-cast bullets and jacketed bullet loads, a .354-inch expander ball was used to obtain greater case-to-bullet tension and increase bullet pull. This likewise serves to improve powder ignition and help prevent squib loads. Cases were expanded with just enough mouth flare to prevent bullets from being shaved or damaged while they are seated. Naturally, all bullets received a roll crimp after being seated to the correct overall cartridge length. For swaged lead bullets without a crimp groove or cannelure, a taper crimp die or Lee Factory Crimp die are excellent options.

CCI 500 Small Pistol standard primers were used throughout, with the exception of loads containing Ramshot Silhouette powder (which is a St. Marks product formerly marketed as Winchester WAP or in OEM form is WPR289). I was experiencing some ignition problems with high extreme spreads using the lightweight Speer 110-grain Gold Dot HP bullets, and switching to a CCI 550 Small Pistol Magnum primer corrected this issue. Primers should be seated .003 to not more than .005 inch below flush, with the anvil in positive contact with the bottom of the primer pocket to assure reliable ignition.

The .38 Special has a rather small pressure and velocity window where loads work properly (i.e. correct pressure for reliable ignition, avoid squib loads), while staying under the maximum average pressure limits. For these reasons, starting loads should not be reduced and neither should maximum loads be increased.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)