In 1857, when the drawn copper-cased 22 rimfire and small Smith & Wesson revolvers to fire it appeared, the percussion era days were numbered. At this time, long-range (1,000 to 1,200 yard) target shooting was becoming popular in Great Britain. Rifles were long-barreled, carefully-bored percussion guns firing heavy bullets covered by a paper patch. With all the leading riflemakers using their own rifling forms to get the best accuracy.

In the early 1860s, William Metford invented another rifling form. It consisted of seven shallow grooves and rounded ends. The twist or spiral of the rifling was not uniform, but became sharper (quicker) toward the muzzle. This was said to prevent the bullet from slipping over the shallow rifling. When the correct powder charge and bullet weight was used, Metford barrels left much less black-powder fouling than normal. Cleaning was found to be needed less often than with other rifling types. Metford’s rifles began winning many target matches.

An early Gibbs hammer double using the Jones screw-grip and chambering the 461 No. 2 Gibbs cartridge.

A riflemaker from Bristol noticed the success of the Metfords. George Gibbs was well-known as a maker of fine match rifles. He approached Metford with the end result in 1865, Gibbs acquired the sole right to use Metford rifling in his barrels. Later, Westley Richards was also licensed to use Metford rifling. Percussion match rifles were made by Gibbs for several more years, but he knew cartridge rifles were coming once the details of drawing large cases were worked out.

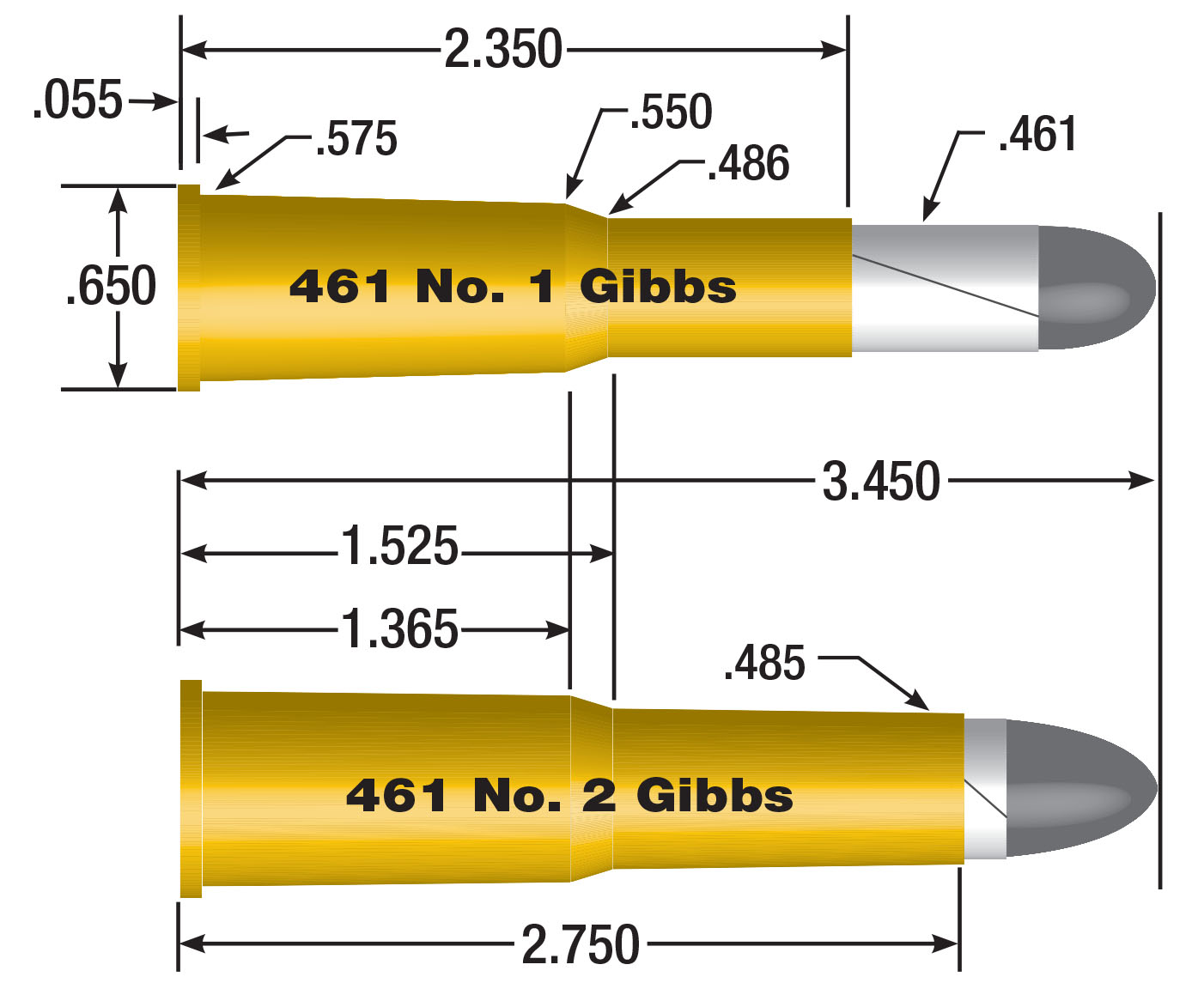

A 480-grain, 45-caliber bullet (center) shows the difference between a 461 No. 1 Gibbs target cartridge (left) and the longer-necked 461 No. 2 (right) that was intended mainly as a hunting round.

Gibbs now needed an action for a cartridge-match rifle. We have all heard the story of the legal battle to determine who would patent the design of a hammerless, falling-block, single-shot action that came to be known as the Farquharson. Obviously, John Farquharson won over Alex Henry. His patent, No. 1592, was sealed on January 3, 1873. The next day, the process of reassigning the patent began. The new owners were John Farquharson, William Metford, George Gibbs and Thomas Pitt. Gibbs had his cartridge rifle action for both long-range target and large-bore hunting rifles.

No definitive date of introduction could be found for the 461 No. 1 Gibbs (that wasn’t called that until the No. 2 appeared in 1881). This is perhaps due to the business being destroyed by bombing in World War II. All records were lost. A British author, writing years before the war, stated that the Farquharson action was acquired by Gibbs in 1870 and immediately chambered in 461 Gibbs, while showing an illustration of the No. 2 cartridge! This is all obviously incorrect because no one knew of the action until it was shown at Wimbledon in July 1872.

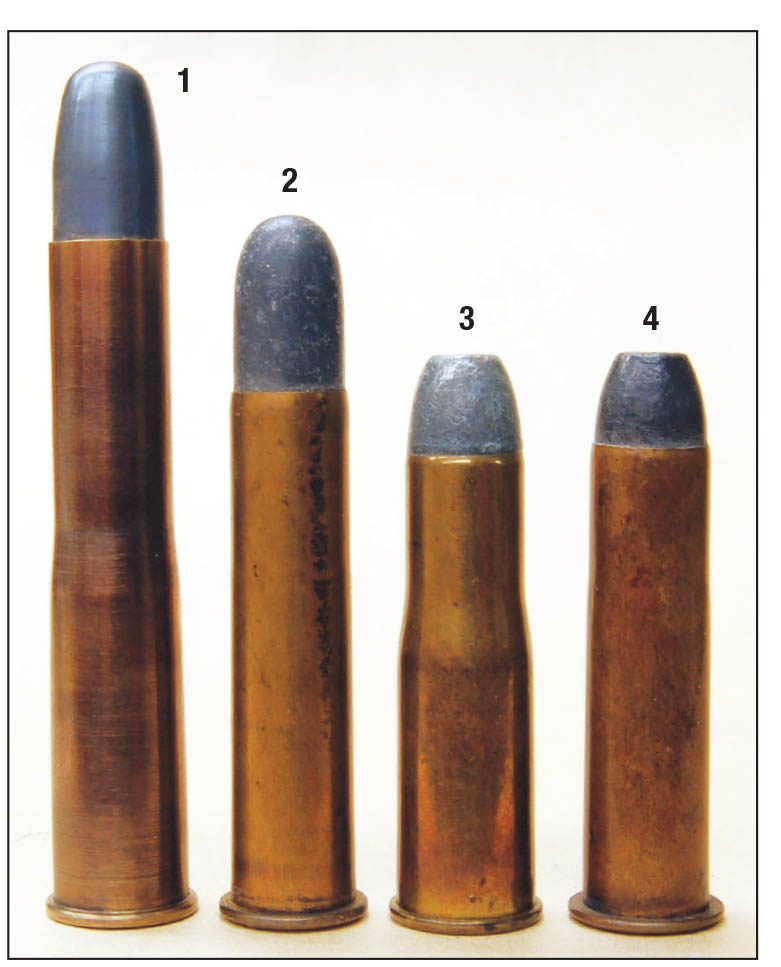

Shown for comparison: (1) a 461 No. 1 with a paper-patched target bullet, (2) a 461 No. 2 Gibbs also with a paper-patched bullet fired in single- shot or target rifles and (3) a 461 No. 2 Gibbs with a lead bullet crimped in place for use in double rifles.

The ammunition firm Eley Brothers, of London, began drawing copper cases in 1870 and solid-brass cases in 1874. Gibbs needed the strength and precision of drawn brass because cases would be used for target rifles firing up to 100 grains of powder. Prior to this, the few large-bore rifle cartridges available in Britain used the Boxer case. This was basically .005-inch thick sheet brass wrapped around a mandrel, one end formed inward to about close it, then a steel washer to serve as a rim riveted on. The rivet was hollow to form a primer pocket holding a centerfire cap and anvil. Bullets were seated deeply in the case and often held by that unique British creation – the stab crimp, which was several indentations around the case neck that look like they were made with a hammer and ice pick. Such a thing would not do for target cartridges.

Beginning in 1870, Eley also offered to produce proprietary cartridges for individual gunmakers. The first seems to have been for a William Soper. Called the 450 Soper 2½ inch, it may have originally used a Boxer case, but was changed to drawn copper then drawn brass for use in Soper’s sporting rifles. Of importance to us here is that the round has the same base and rim diameter as the earlier 500 2 inch, which used a Boxer case. In fact, there are at least six of these Boxer-cased 500 cartridges from 1½- to 3-inches in length. Gibbs used the same base and rim diameters on his 461 No. 1 and No. 2. It appears both Soper and Gibbs were waiting for Eley’s drawn brass case.

Studying the 461 No. 1 cartridge shows the bullet just barely inserted in the case (see photo). This seems to indicate the case was just a convenient means to carry ammunition to the range. A specifically reamed chamber throat then aligned the bullet with the bore since black-powder fouling was easily removed through the open breech. The bullet diameter was 461 inch.

British rounds contemporary to the 461 No. 2 (1) are military such as a (2) 450, 3¼-inch coiled (Boxer) case, (3) a 450, 3¼-inch drawn brass, (4) a 577/450 coiled, (5) a 577/450 drawn brass and (6) a 450 No. 1 Musket.

The original loading of the 461 No. 1 was a 480-grain, paper-patched bullet and 85 grains of black powder (all powder charges are grains measured by volume, not by weight). This was a target load for heavy match rifles. Gibbs also offered his Farquharson single shots in light-hunting-rifle form. The hunting load was a bit different in that it contained a 540-grain bullet seated down in the case neck normally. The powder charge was 75 grains.

Powder charges for the 461s and all old black-powder rounds were given in grains by volume, not by weight. The powder on the left is 70 grains weight. The powder on the right is 70 grains bulk, which weighs just under 60 grains.

The 461 No. 1 was a powerful black-powder round. Its first hunting load produced about 2,000 foot-pounds of muzzle energy, adequate for most any game in the days before telescopic sights. It was more powerful than the American 45-70, yet still considered a medium bore by the British. Classification of large bore went to the 10-, 8- and 4-bore rifles.

Gibbs later offered a 360-grain hollowpoint bullet ahead of 90 grains of black powder. This was an express load developing more than 1,500 feet per second (fps) muzzle velocity and just under 2,000 foot-pounds of energy. A 570-grain bullet was available somewhat later, but no velocity could be found.

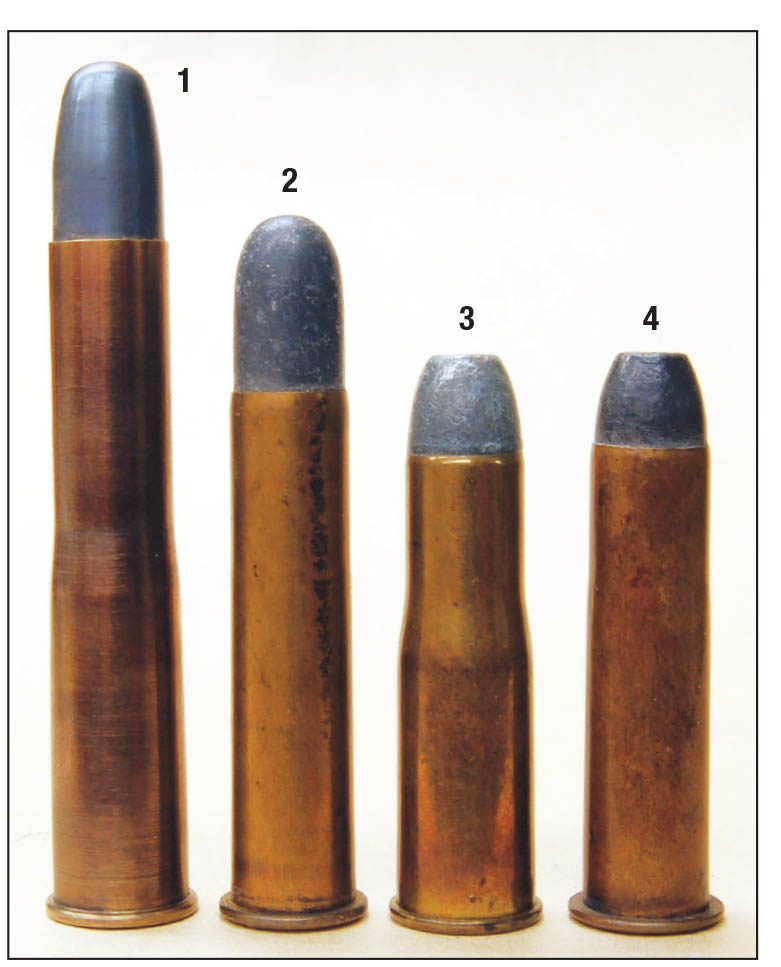

Similar to the (1) British 461 No. 2 Gibbs and available at the same time are the (2) American 45-70, (3) 45-75 and (4) 45-60.

The year 1881 saw the 461 Gibbs become the 461 No. 1 Gibbs with announcement of the 461 No. 2 Gibbs. The only difference was the new .4-inch longer case neck on the round. Although Gibbs chambered his rifles for other popular cartridges, the 461 No. 2 Gibbs was his preferred round for sport hunting. The longer neck gave more room for powder. Two hunting loads were immediately available. One used the 570-grain bullet of the No. 1 Gibbs cartridge but with 90 to 95 grains of powder. Velocity was listed as 1,350 fps, yielding well over 2,000 foot pounds of muzzle energy. The original 360-grain hollowpoint was now backed by 100 grains of black powder. Muzzle speed was said to be more than 1,700 fps. That’s north of 2,300 foot-pounds of energy. Also included was the 480-grain military load with the same powder charge as the No. 1 Gibbs cartridge, but the longer neck gave room for a card and grease wad preferred by many target riflemen.

Of interest is that famous African hunter Frederick Selous often mentions Gibbs Farquharson 461 Gibbs single shots in his books. It is not clear whether he means the No. 1 or No. 2, but it’s probably the No. 1 cartridge. Gibbs Farquharson’s exist, chambering both rounds that are said to have belonged to Selous. He seems to have favored the 461 Gibbs for lion using the 570-grain bullet.

Being proprietary cartridges, rifles and ammunition were sold only through the Gibbs company. Therefore, the rounds did not appear in ammunition makers catalogs and thus, not many cartridge books today.

Nevertheless, both were popular anywhere in the British Empire where game was hunted until well into the smokeless era. Gunmaker Thomas Turner even copied the 461 No. 1 Gibbs calling it the 461 Turner No. 8!

Neither of Gibbs’ 461s made the transition to smokeless or nitro-for-black loadings. One source indicated original black-powder hunting loads were available into the 1930s. They deserve a special place in any collection of the earliest drawn-brass cartridges.

.jpg)