In Range

Williamson Derringer

column By: Terry Wieland | February, 19

When Henry Deringer introduced his pocket pistol in the 1830s, he probably never suspected it would create a whole new class of firearm. “Deringer-Philadelphia” was the simple inscription born by genuine Deringers, whereas his imitators generally spelled the name differently. Today, the word “derringer” (two ‘r’s) denotes a class of pistol that is very simply defined: It fires one shot or two and is small enough to be carried in a pocket or up a sleeve.

The development that fostered a significant improvement in pocket pistols, and allowed them to be radically reduced in size, was the percussion cap. Without the projections and sharp edges of a flintlock, a pocket pistol could be smaller and easier to draw, whether from a tradesman’s pocket, a gambler’s boot or the fur muff of a lady.

Such diminutive pistols existed for one purpose only: Last ditch self defense. They had one shot, and accuracy beyond a few yards was pure imagination – but then, so was power. The longest practical distance was across a poker table, although Booth demonstrated conclusively that a theater box could also be accommodated.

Because of John Wilkes Booth, and the popularity of the Derringer among riverboat gamblers and sportin’ ladies, such guns acquired a distinctly unsavory reputation. Later assassinations, such as that of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, in which assassins employed pistols that were indirectly descended from the Deringer, did not help their reputation but – not surprisingly – did nothing to hurt the company’s sales.

The original Philadelphia Deringer would, in all likelihood, have remained the Manton of its class had not percussion guns been superseded by breechloaders beginning in the 1850s. Between the heyday of percussion, however, and the ascendancy of the cartridge pistol in the 1870s, lay a 20-year period of transition in which scores of inventors worked on various methods of breechloading.

Although early cartridge Derringers came in many calibers, large and small, probably the most effective was the .41 Short Rimfire, a cartridge of the same bore diameter as the original Deringer. A .41-diameter bullet, or ball, had sufficient weight and striking power to dissuade an assailant, yet it was not so large that it made the gun hard to handle.

One huge advantage of the original Deringer, a muzzleloader, was that ammunition supplies were rarely a problem. All a person needed were percussion caps and gunpowder – both readily available – and either a supply of lead balls or the wherewithal to cast some more. As the great movement West became a flood after the Civil War, this was no small consideration. Speed of fire and convenience were all very well, but if you ran out of ammunition and could not obtain more, it left you with a rather inefficient club. In the case of the pocket pistol, it was not even that.

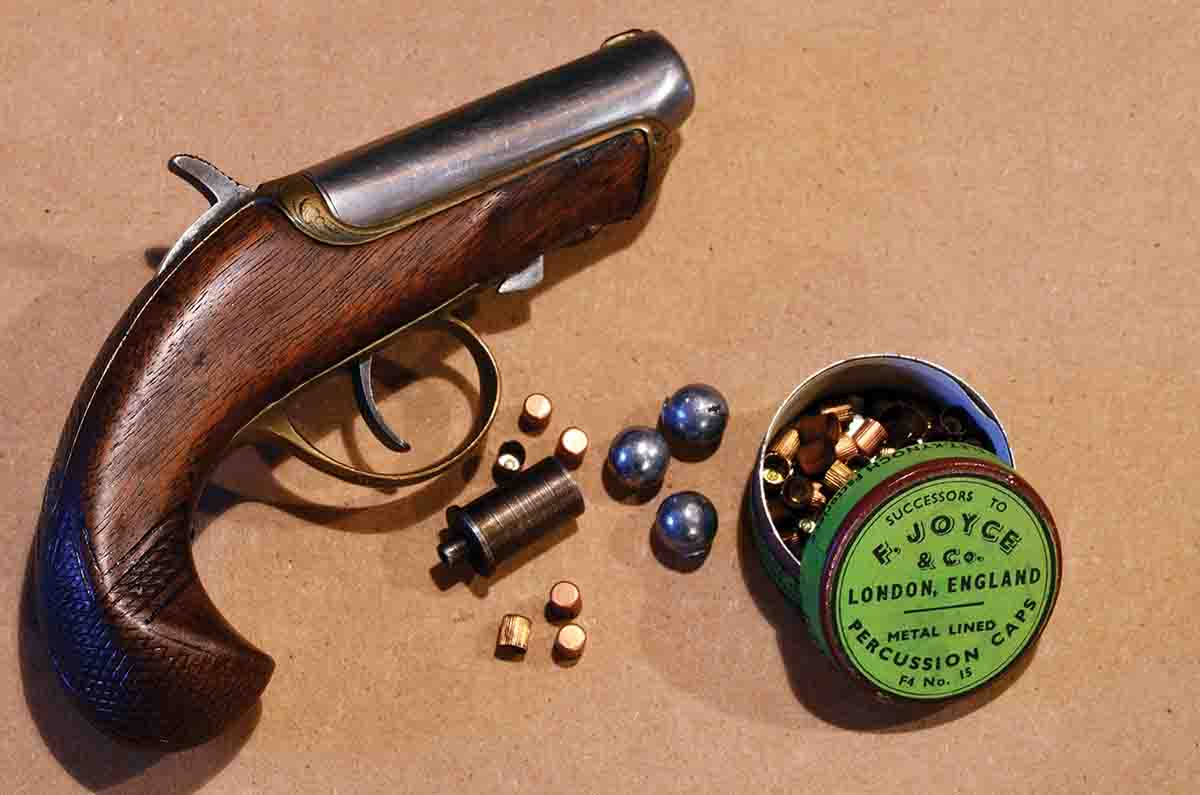

In 1866 New York inventor David Williamson patented a design for a Derringer that combined the convenience of the .41 Short Rimfire cartridge with the capability, in a pinch, to resort to the proven percussion system. The “Williamson Derringer” did this by means of a reusable chamber that took the place of the cartridge.

One feature that commands a premium is the reusable “auxiliary chamber.” This is important to both the serious collector and a shooter who wants to actually use the gun. In the case of the Williamson Derringer, not only is .41 Short Rimfire ammunition hard to come by, so is the auxiliary chamber that allows getting by without it. As with most such accoutrements, they became separated from their parent pistols, and have become collector’s items in themselves.

In the 1960s, Dixie Gun Works sold a replacement chamber for the Williamson Derringer, and prospective purchasers should be wary. A gun accompanied by an auxiliary chamber may be described as “all-original” when, in fact, the chamber is of modern manufacture. This would not matter to a user, except for the fact that the after-market auxiliary chambers do not work well, if they work at all.

The auxiliary chamber is made of steel, turned on a lathe and resembles the cartridge case, except that in place of a primer pocket it has a nipple that accommodates a percussion cap. When the pistol is fired, the striker hits the percussion cap and ignites it, exactly as it would a primer or the rim of a cartridge. The problem with the new chambers is that their nipples are often too short, and the striker does not reach the percussion cap.

Conversely, the original auxiliary chamber is quite efficient and easy to use. The shooter simply loads it with 6 grains of FFFg black powder, places a .375-inch diameter round ball in the mouth and presses a percussion cap onto the nipple.

To load the pistol, the barrel slides forward, away from the standing breech. Holding the gun and cartridge upright to keep the ball from falling out, the chamber is inserted into the gun. The ball is held firmly in place by the chamber walls, and the barrel then slides back to the rear to lock up. At that point, all the shooter has to do is cock the hammer and pull the trigger.

The Williamson is notable not for being unique, but for being an elegant solution to the problem. The sliding barrel easily accommodates the extended nipple of the auxiliary chamber, whereas a break-action gun would not. The chamber itself is simple and cheap to make.

One might think, Aha! You could buy several auxiliary chambers and increase the firepower, but that’s hardly true. Rather than fitting down into the chamber, the ball perches on the mouth and is held in place by the pistol’s chamber walls, so you can’t load a supply in advance. And given the emergency nature of the pistol, where one shot solves the problem or else it doesn’t get solved, it would be pointless to try. The auxiliary chamber’s real purpose is not to increase the firepower but to keep the gun firing when .41 Short Rimfire ammunition is not available.

Although Williamson Derringers are rare, they are not terribly expensive. As this is written, most seem to run around $850. Possibly this is because they occupy an arcane corner of an admittedly restricted field of collecting. For anyone interested in the period of transition from percussion to central-fire cartridges, however, they provide intriguing insight. And, if nothing else, they make a firearms enthusiast appreciate the convenience of that High Standard Derringer tucked in his pocket, out of sight but ready for action.