Precision, and Then Some

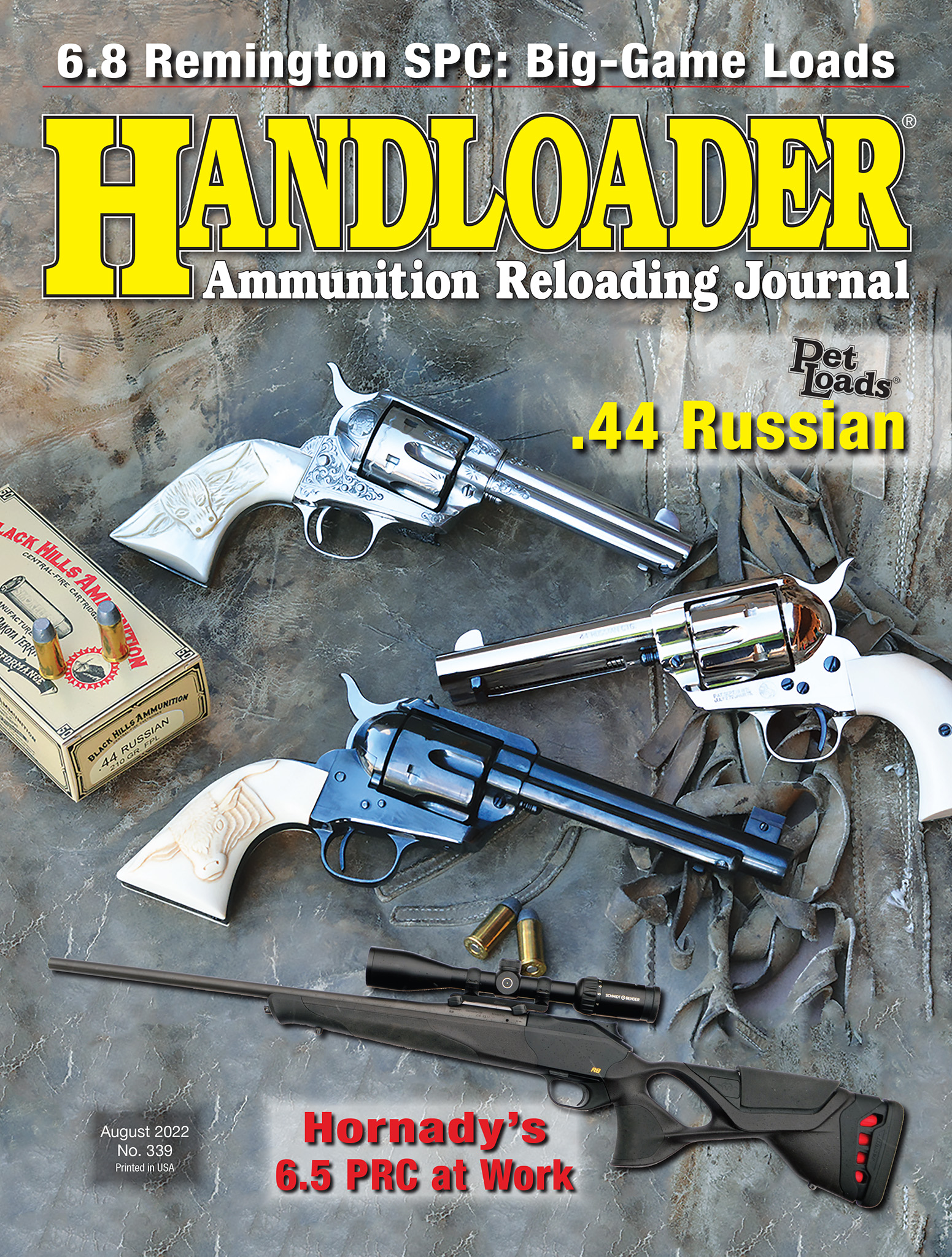

Hornady’s 6.5 PRC at Work

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 22

This being an article about Hornady’s 6.5 PRC, the simplest course would be to advise everyone to buy one, assure them they’ll never regret it, and go on to something else. That would take care of the “what.” As to the “why,” that requires a little history, and some explanation.

These days, anyone contemplating the purchase of a rifle in 6.5mm (.264) could be forgiven for finding himself hopelessly confused. In fact, I find myself in the same situation, and I’ve been a sometime-devotee of the 6.5mm in its myriad forms since 1988.

In that year, I bought a Parker-Hale 6.5x55 Swedish, and swiftly discovered that articles about it, or even distantly related to it, were unsaleable to the gun magazines. “No one’s interested in 6.5s,” I was told. “Americans like .30s.” Sure enough, write yet another piece about the .308 or .30-06 and you’d be sure to flog it someplace.

This is not to say that serious gun writers, the big gun companies and a horde of wildcatters did not attempt to interest the American shooting public, and there was always a coterie of collectors who amassed any number of arcane European military rifles chambered in what seemed like endless variations on the same 6.5-by-50-something theme. But mainstream interest? No, thanks.

Today, the situation is completely reversed: There are so many cartridges, manufactured in high-quality factory form by so many ammunition makers, and so many excellent rifles being turned out, it’s hard to know where to start. This is particularly true in what I would call the 6.5’s natural sweet spot: That middle ground where you are shooting a reasonably heavy bullet downrange at a reasonable velocity, and suffering only reasonable recoil in a rifle of reasonable hunting weight.

Of course, not everyone has the same idea of “reasonable,” so here’s mine: 140-grain bullet, 2,850 feet per second (fps), 7½ pound rifle, 24-inch barrel. With good handloads, the 6.5x55 Swedish will deliver that comfortably, as will most of its centenarian military brethren, although a shooter probably wouldn’t want to stress some of the rifles in which they’re chambered.

Naturally, efforts have been made to deliver a 6.5mm hotrod that will lay the daisies low. The first American to do so was Charles Newton, with his .256 Newton, unveiled in 1913. Newton used British terminology, measuring by bore rather than groove diameter, but it was a 6.5. In fact, it was almost identical to the later wildcat 6.5-06, which many writers – pointlessly, alas – hailed as the ultimate all-around big-game cartridge for North America. The Newton did not deliver what hunters would call sizzling velocity – 2,760 fps with a 129-grain bullet – but it was certainly respectable. One thing it did establish was the notion that 129 grains is the ideal weight for a 6.5mm bullet. That’s debatable, but it’s also the reason one can find so many 129-grain 6.5s around today.

Probably, we should not forget to mention the 6.5 Remington Magnum, which came along in 1966, chambered in the very strange Model 600 bolt-action carbine, or Remington’s next attempt, 30 years later, with the .260 Remington. Neither set the shooting world ablaze.

In light of this history, one would think everyone would give up on the 6.5mm, but one thing kept it alive: Long-range target shooters loved its inherent ballistic excellence, and sooner or later, one of the factories was sure to hit on a winning commercial formula. That factory was Hornady. The company correctly analyzed the history, isolated all the factors that had sabotaged every other 6.5mm along the way, corrected them all, and produced the 6.5 Creedmoor, the most successful cartridge introduction of this century.

However, buoyed by the success of the 6.5 Creedmoor, Hornady decided to go one better. For reasons that escape me, during the binge of “short magnum” cartridge introductions that began with Winchester’s .300 WSM in 2000 (based on a concept originated by writer Rick Jamison and confirmed in a court of law) no one saw fit to include the 6.5mm. Since Hornady had created the .300 Ruger Short Magnum, which followed the short, fat, parallel-side pattern of the WSMs, the company decided to neck that down to .264.

The result was the 6.5 PRC, which stands for Precision Rifle Cartridge, and while that might not be the most evocative name ever given a cartridge, it’s certainly accurate. As is the cartridge itself.

I was introduced to the 6.5 PRC on a July afternoon in South Dakota when the temperature topped out at 104 degrees Fahrenheit. There was not a cloud in the sky and a gusting, hot wind knocked over umbrellas and rocked the shooting benches. It was no day to be sitting in the middle of a prairie dog town, but there we were.

The rifle was a Hardy Hybrid, a switch-barrel imported from New Zealand by Legacy Sports. Legacy’s Andy McCormick was spotting for me as we waited for prairie dogs to appear on a distant hillside. One kept putting his nose out, I kept poking at it and missing by a few inches, and Andy kept calling out the adjustments as the wind rose and fell. Finally, after about 10 minutes, the rodent figured it was safe, emerged, and sat up with his nose into the wind. I put the crosshair under his nose and a little to the left, pulled the trigger, and he simply disappeared. Ceased to exist.

The range, according to Andy’s laser rangefinder, was 427 yards.

Our ammunition was factory Hornady Match, with a 147-grain ELD bullet. We also had some factory Hornady hunting ammunition with the 143-grain ELD-X bullet. My prairie dog went down at the hands of the match ammunition, but the hunting stuff was shooting just as well. It was a revelation.

Alas, at that moment – and continuing for months afterward – shipments from Hardy were tied up on freighters waiting off Los Angeles and Legacy was out of stock on virtually everything. Fortunately, Blaser of Germany had recently added the 6.5 PRC to the list of calibers available for its R8 straight-pull, switch-barrel rifle, and since I had one of the new (and rather futuristic) R8 Ultimates just sitting here…

Ammunition from Hornady was also in short supply, and the two superb bullets mentioned above, intended specifically for the 6.5 PRC, were practically unobtainable, not just then but for months afterward. Eventually, Seth Swerczek at Hornady managed to corral some for me, Lapua supplied some of its superb brass and we were ready to proceed.

The problem with obtaining suitable bullets extended to every other company as well, but fortunately, I had some squirreled away that fitted the 6.5 PRC’s intended use. I assembled half a dozen, ranging in weight from 129 grains to 147, and picked out some near-maximum loads, working in a variety of powders and powder-makers from what I had available. Loads using the two Hornady bullets were taken from Hornady’s own load data. The purpose was not to develop an ideal load for the rifle, but to see how it performed with a cross section of loads chosen at random.

The accompanying table tells us what we need to know, including two major surprises: First, the Hornady factory ammunition that I used as a standard to measure results out-performed every handload in group size, with the match ammunition edging the hunting stuff. Second, the velocities were universally lower than either Hornady called for in its ballistics charts for factory ammunition, or the velocities claimed in every piece of load data.

Given different circumstances – availability of powders, bullets, and different brands of brass – it would be interesting to see if those velocities could be increased, but since most of the loads tested were at or near published maximums, it’s hard to see how. (I ruled out chronograph malfunction, because I have tested my Competition Electronics ProChrono against other makes in the past, and it has never failed.)

In the case of the Sierra 142-grain Sierra MatchKing with IMR-7977 powder, Hodgdon’s data shows a 24-inch barrel and velocity that should have been around 2,850 fps, but with my Blaser’s 25.5-inch barrel, it was only 2,743 fps.

Loads for the Hornady bullets were taken from Hornady data, which it compiled using a 26-inch barrel on a GA Precision rifle. The load with Hodgdon H-1000 was supposed to deliver velocity of 3,100 fps, but was only 2,915 fps.

I very much doubt velocity discrepancies will have any such impact on the 6.5 PRC, although the comparison is uncanny in another way. The 7x61 S&H was the first modern attempt to tailor a rifle, cartridge, bullet and load specifically as a package that would out-perform all others. It was the best that Phil Sharpe, Schultz & Larsen (the Danish maker of target rifles) and Norma Projektilfabrik of Sweden could come up with – and velocity aside, it was a fine combination that should have done better in the marketplace than it did.

Maybe it was just before its time. At any rate, the time for such a venture has arrived, and Hornady has more than succeeded with the 6.5 PRC. In my opinion, it’s the optimum manifestation of the 6.5mm, and long overdue. So there’s the “why.” Buy one. You won’t regret it.

.jpg)

.jpg)