Reduced Rifle Loads

Powder Options That Are Often Overlooked

feature By: John Barsness | February, 17

Ever since some German cut spiral grooves inside a musket barrel, the overall trend in hunting rifles has been more velocity, both at the muzzle and downrange. So why would any twenty- first-century handloader use reduced loads, especially with relatively blunt bullets? Many hunters used to develop reduced loads because they owned relatively few rifles. This was common before World War II, and articles in shooting magazines frequently included reduced loads. Then, after the postwar economic boom took off, new cartridges appeared for every use, and affluent Americans bought specialized rifles for various kinds of hunting.

They may not have needed all those rifles, but in a “consumer society,” owning more stuff became a way of keeping score. Why would any hunter own several new rifles, chambered for nifty new cartridges for everything from squirrels to moose, then use reduced handloads? That would be admitting their Rocky-to-Bullwinkle battery wasn’t perfect.

The perfect-cartridge trend continues today, but social changes have revived reduced handloads, including Obama’s election and reelection. Ammunition and handloading components became harder to find, and many shooters who thought rimfire ammunition would always be cheap and abundant were disillusioned. Many decided reduced handloads made more sense than buying .22 Long Rifle ammunition costing $50 to $75 a brick – when it could be found.

The overall population of the U.S. is also aging, especially among shooters. As people age, they often downsize by moving into an apartment or smaller house. While younger shooters may find it unbelievable, many retired shooters eventually decide it’s possible to own too many rifles, so they sell some, spending the money on other stuff, including visits to distant grandchildren.

They still like to shoot and handload, but after decades of owning the perfect rifle for every purpose, they found some rifles got used far more than others. So they worked up loads for fewer rifles, often reduced loads so their grandchildren could comfortably hunt squirrels with Grandpa’s deer rifles or hunt deer with Grandpa’s moose rifles. Often Grandpa himself eventually preferred reduced loads, because packing out squirrels was easier than packing out moose, and lighter recoil is easier on older shoulders.

Even when financially comfortable, many retired shooters don’t see any sense in spending more money when the same results can be achieved with less money. Why not use milder loads to take advantage of cheap, abundant .223 Remington brass, when full-power .223 loads aren’t necessary for shooting holes in paper, or even many varmints? Some load a .22-250 Remington or .243 Winchester down to .223 levels, not only saving per-round costs but also reducing recoil and extending barrel life.

Even nonretired handloaders find uses for reduced loads. I’ve worked up a bunch over the decades, including small-game loads for slipping into the chamber if a blue grouse or turkey appears during a fall hunt for big game (legal here in Montana). I’ve developed milder hunting/practice loads for really big rifles. Not only are they more pleasant to shoot but are also much less expensive than full-power handloads costing up to $3.00 a round. Then there are old rifles unsuitable for high- pressure handloads, because of design, materials or both; several of mine were made from the 1880s to the 1920s.

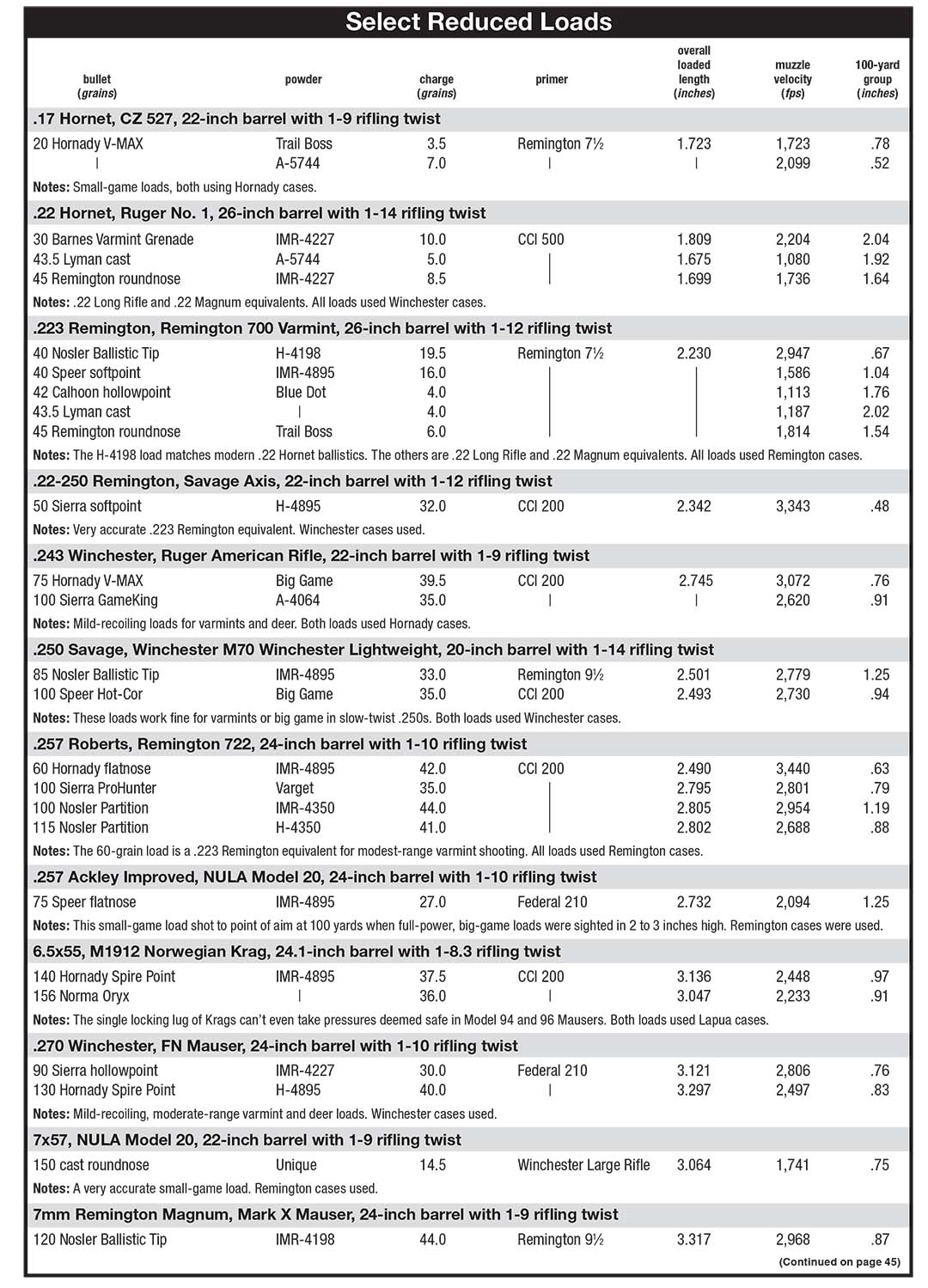

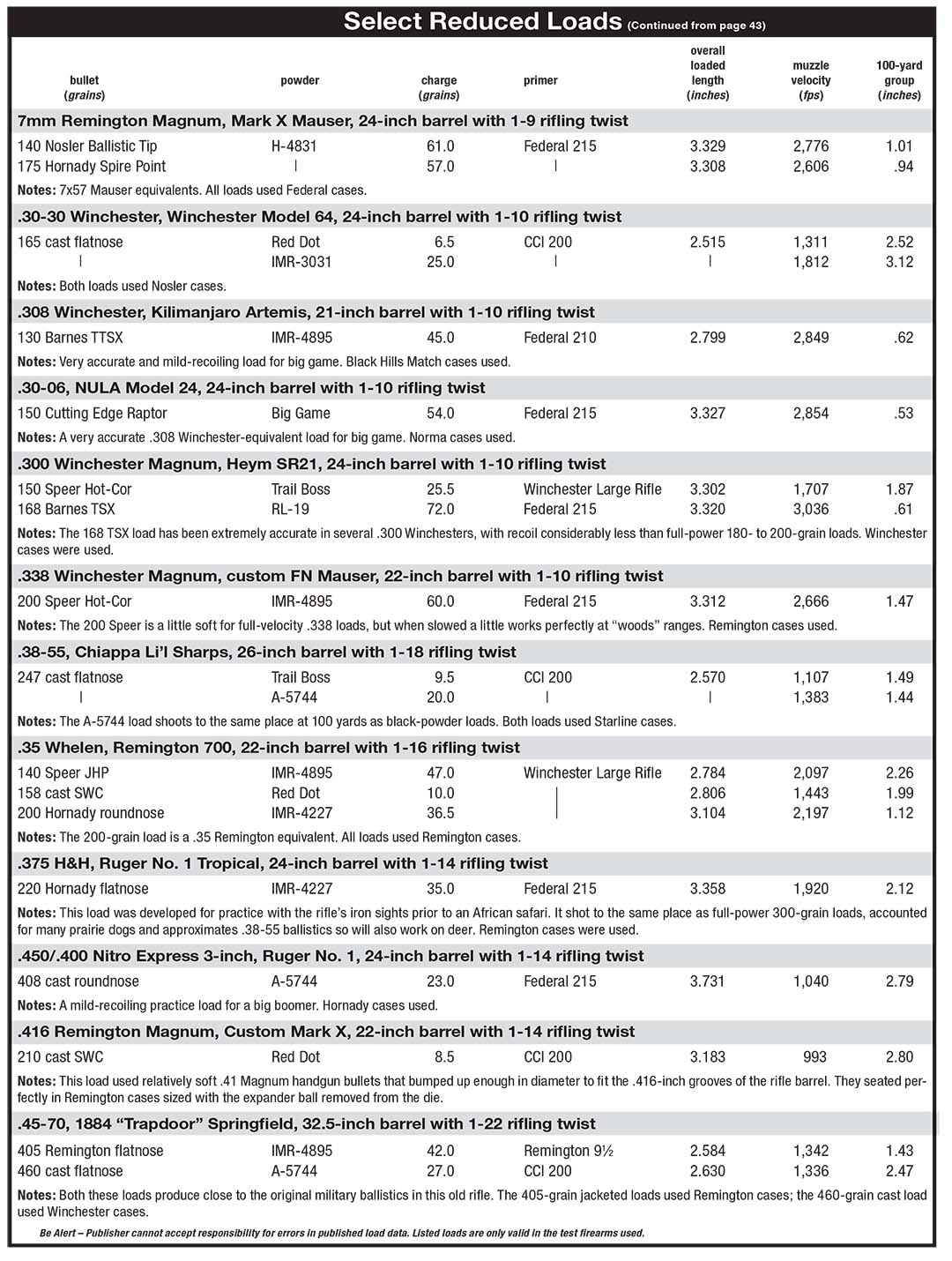

Some of those reduced loads are listed here, but an old proverb states: “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” The same general principle applies to handloading, and thanks to many knowledgeable shooters, I eventually learned several basic principles of working up reduced loads for almost any rifle cartridge.

There are two basic kinds of reduced rifle loads: “somewhat” and “really reduced.” Somewhat- reduced loads are easiest, because all one has to do is cut back a full-power powder charge. This sounds simple enough, but experienced handloaders have read warnings about not reducing charges of slow-burning powders more than 10 percent, due to the possibility of blowing up a rifle because of “pressure excursions.” In this context, excursion does not mean a trip to visit the grandchildren in Spokane. Instead, it means “a deviation from a direct, definite or proper course,” as when a rifle blows up. Nobody really knows why such excursions occur, but one guess is that only part of the powder charge initially ignites, pushing the bullet into the lands and blocking the bore before the rest of the powder takes off. Since smaller charges of faster-burning powders cost less anyway, why take the risk?

In general, powders with a burn rate around IMR-4350 or slower should not be used in charges lighter than listed starting loads, partly because they’re more difficult to ignite. This especially applies to spherical powders, because their tiny granules include very resistant coatings to slow the burn rate.

“Starting” loads often work just fine for somewhat-reduced loads, dropping muzzle velocity just enough to make recoil far more tolerant, and believe it or not, a 7mm, .300 or .338 magnum will take big game neatly even when not pushed to the maximum velocity. Back in the 1970s, when the 7mm Remington Magnum was still considered the new “in-cartridge,” a friend here in Montana killed a pile of deer, black bear and elk years before he bought his first chronograph and discovered the muzzle velocity of his “magnum” handload was slower than 150-grain, .270 Winchester factory loads.

Even moderate cartridges work fine with starting loads, especially older rounds with mild pressure limits as set by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI). The .257 Roberts essentially becomes a .250 Savage with SAAMI-level starting loads, and the .250 Savage has been killing big game neatly for over a century. (The .250’s SAAMI pressure is even lower, so its starting loads are even more pleasant yet still effective.)

Some moderate burn-rate rifle powders work well in a wide range of pressures and velocities. Probably the most frequently used powders for somewhat-reduced loads are the similar IMR-4895 and H-4895, but others work too. One advantage of reduced charges of extruded, single-based powders, like the 4895s, is very predictable pressures and hence velocities. If a handloader desires a specific muzzle velocity, the reduction is directly proportional to the reduction in powder charge: reduce a full-power charge 25 percent, and muzzle velocity drops 25 percent. Velocity math with double-based powders such as Accurate 5744 isn’t quite as precise, but it gets a handloader in the ballpark.

All this used to be well known among handloaders in the years after World War II. Not nearly as many powders were available then, for the same reasons new vehicles and sporting rifles were also scarce: Factories had been converted to war-time production, and it took a while to reconvert afterward. There were, however, vast stocks of “military surplus” powders, and many soon became available to handloaders, largely due to Bruce Hodgdon. These included the powder known today as H-110, designed for the .30 Carbine cartridge; H-335 and BL-C(2), different lots of the same powder; H-4895, actually the IMR-4895 designed by DuPont for the 150-grain M2 Ball load used in the Garand rifle; and H-4831, a powder used in 20mm cannon rounds.

I started using IMR-4895, because it was more commonly available in Montana. In fact, my supply is still kept in a metal canister originally containing eight pounds obtained about 15 years ago. The thin, rectangular canister takes up less space in my powder storage than today’s rounder plastic jugs, so when it’s depleted I refill the can. So far, every new batch of IMR-4895 has been so close in burn rate there’s no practical difference.

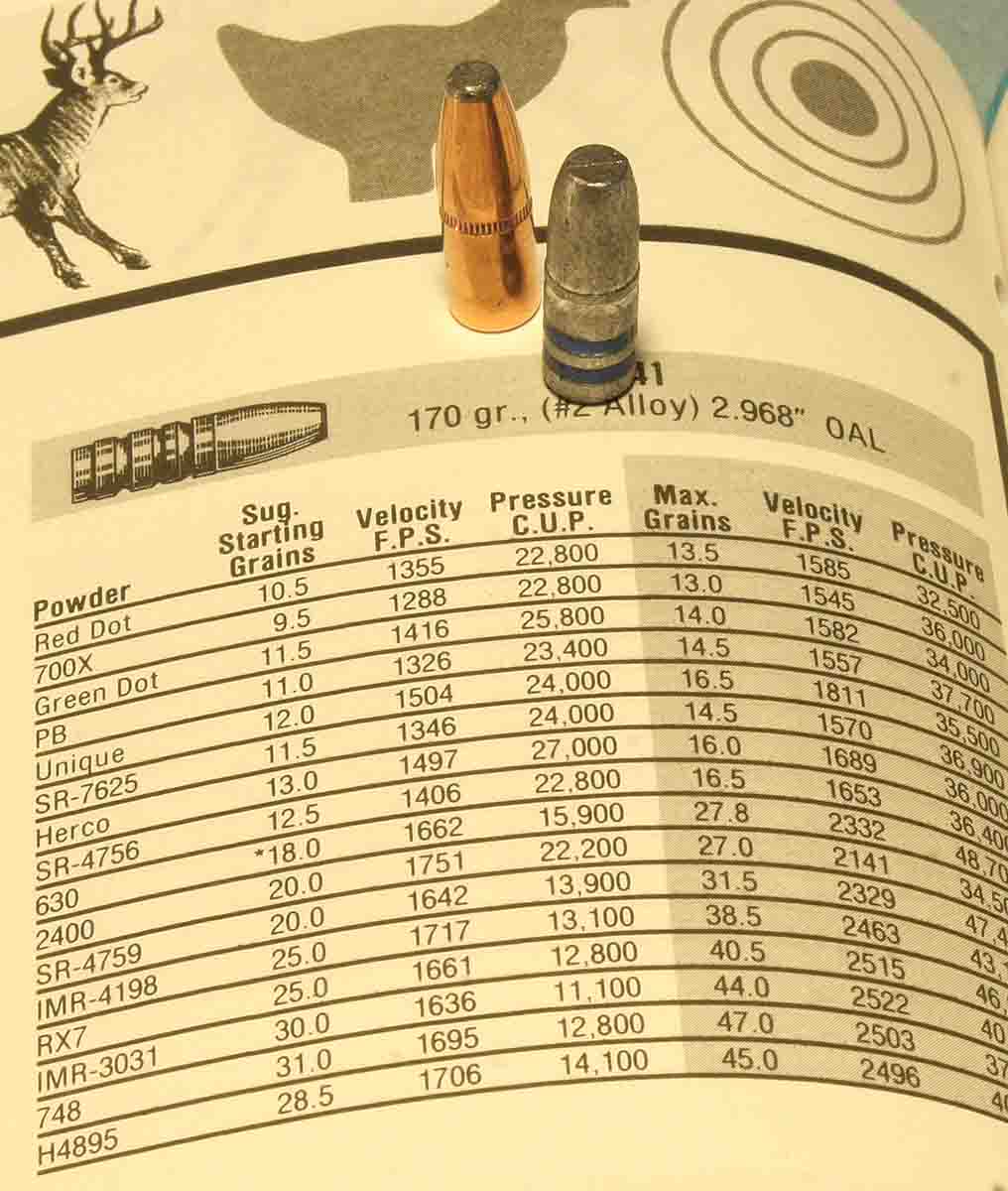

Other long-time IMR powders also work fine for reduced loads, including IMR-4227, IMR-4198 and IMR-3031, which were used a lot back when 10 zillion powders weren’t available. Back then, most sources listed what many twenty-first-century handloaders would consider stupidly inadequate velocities, because companies listed every suitable powder.

A good example is the Number 6 Speer Manual For Reloading Ammunition, circa 1964, purchased with profits from my paper route back in 1966. Unlike today’s Hodgdon data, the .30-06 data for 180-grain bullets lists IMR-3031 (42.0 grains for 2,499 fps), a powder now almost as unstylish as “big back” TVs. Today’s velocity freaks wouldn’t even consider such a load, even though it certainly wouldn’t do elk any good at “timber” ranges. A muzzle velocity of around 2,500 fps ensures spitzer expansion out to at least 200 yards, and my hunting notes over the last 40 years indicate 90 percent of big game is shot within 200 yards.

Many companies no longer test certain powders in certain cartridges, because so many customers want more velocity, the reason some handloaders never throw away older loading manuals, even with plenty of “free” data available on the Internet. One of my favorites is a booklet published in 2002 by the IMR Powder Company, before IMR became part of Hodgdon, because data for many popular

rifle cartridges includes fast-burning powders, such as IMR-4227 and IMR-4198. To millennials, this may seem ancient information, but even in 2002 IMR powder was being made at the same factory in Canada where most is produced today, and the same data works fine. (Some IMR powder is now made in Australia to the same specifications.)

Another good source for really- reduced data is Lyman’s cast-bullet manual. Its loads also work with jacketed bullets because, contrary to what many handloaders believe, jacketed bullets actually result in less pressure with the same loads, since they don’t seal the bore as completely as softer cast bullets. (If you don’t believe this, compare various sources of data for cast and jacketed bullets. The maximum charge is normally less for cast bullets of the same weight, though muzzle velocities are often similar.)

Some companies also publish simple formulas for reducing loads with specific powders. Along with the 60 percent rule for the 4895s, Hodgdon lists a formula for Trail Boss, a powder designed for really-reduced loads: Fill the case to the base of a seated bullet, then weigh that charge and use it as the maximum load – though pressure will always be less than maximum for the cartridge. Use 70 percent as a starting load. Trail Boss is an excellent choice partly because its bulk prevents the primary danger of reduced loads, i.e., double- charging, and Hodgdon also lists some specific loads for larger modern cartridges, including one for 150-grain bullets in the .300 Winchester Magnum.

Accurate 5744 is just as versatile as the 4895s. Like them, it also works fine as a full-charge powder for cartridges such as the .223 Remington and .308 Winchester, but it does so well with reduced charges that it’s a top choice for making smokeless rounds for black-powder rifles. Fill a case with 5744 to the base of a seated bullet and use 40 percent of that charge’s weight as a starting load. Consider 48 percent maximum with cast bullets and 60 to 65 percent maximum with jacketed bullets – yet more evidence that cast bullets produce more pressure.

Some powders popular for really- reduced handloads are primarily meant for handgun and shotgun cartridges but work well at handgun/shotgun pressures in rifle cartridges. Normally these are double-based, providing more energy in smaller charges. My favorite among these is probably Alliant Red Dot, partly because it’s also versatile for 12-gauge reloading and partly because of an article by C.E. Harris titled “The Load” in the 1990 Handloader’s Digest. After considerable experimentation, Harris found 13.0 grains of Red Dot worked well in any cartridge above .35 Remington capacity when using cast or jacketed bullets of “normal” weight. (Sometimes the charge has to be adjusted a little, especially for bullets outside normal weights, including my listed load for the .416 Remington Magnum with 210-grain .41 Magnum bullets.) Similarly, gunsmith and bullet maker James Calhoon experimented considerably with Blue Dot after consulting with Alliant. The Blue Dot loads for the .223 Remington came from Calhoon’s website: www.jamescalhoon.com.

None of the listed loads use any sort of case “filler,” even with very small charges of powder, because I’ve never found a need for fillers, even with the .416 load. I do, however, normally use a dowel or nail for checking the powder level of reduced loads filling less than half the case, to prevent double charges.

Reduced loads are useful, fun and save money. All are more than enough reason for handloaders to add “shrinkage” to their techniques.