Reloader's Press

Loaded for Bear and Other Critters

column By: Dave Scovill | December, 19

The above title once served as the name of a column the late John Wootters wrote in Rifle magazine. Bear hunting wasn’t necessarily the focus of the column in literal terms but served to offer some measure of direction in terms of content regarding handloading in general. The subject might be handloading for the .270 WCF, but the techniques applied and overall view could be of some value for other cartridges, such as the .30-06, .257 Roberts, etc. I took it to mean loading to perfection or purpose, considering bullet design, exterior ballistics, etc.

As a youngster in the 1950s and 60s, I heard the phrase “loaded for bear” from time to time when someone was facing a somewhat arduous or challenging task. It was usually accompanied with hitching up your pants and/or snapping your suspenders and diving into whatever needed to be done.

Around the age of eight or so, we moved into company housing at a logging camp on the west side of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon. I was standing near the maintenance shop one morning while waiting for the school bus when a fully loaded log truck pulled off the road near the shop. The driver jumped out of the cab and walked down the length of the load checking the binders, a standard routine after navigating the oftentimes rough mountain roads. As a rule, however, an unlocked binder could be seen in rear view mirrors.

One of the binders was unlocked and the driver jumped up to grab the lever, and while hanging nearly upside down with one foot braced up under the load, pulled down to tighten and lock the chain. When the lever snapped down, the driver nearly hit the ground, but managed to get one foot down first. As the driver climbed up into the truck cab, the shop foreman who was standing nearby turned toward the shop, muttering “That old gal is sure loaded for bear.”

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but that “old gal’s” name was Emma. She filled in when most of the younger men joined the military during World War II and proved tough enough to stay on after the war. Complete with high-top caulk boots, duck canvas (tin) pants, suspenders, tin hat and homemade pillow ticking shirt, she drove trucks until the environmentalists drove most of the logging industry out of the Northwest in the mid-1960s.

As one of the last big logging camps left in the Northwest at the time, some workers lived in the camp during the week and went home on weekends. Others lived in camp full time. In effect, it was a 24/7, self-sufficient “loaded for bear” operation.

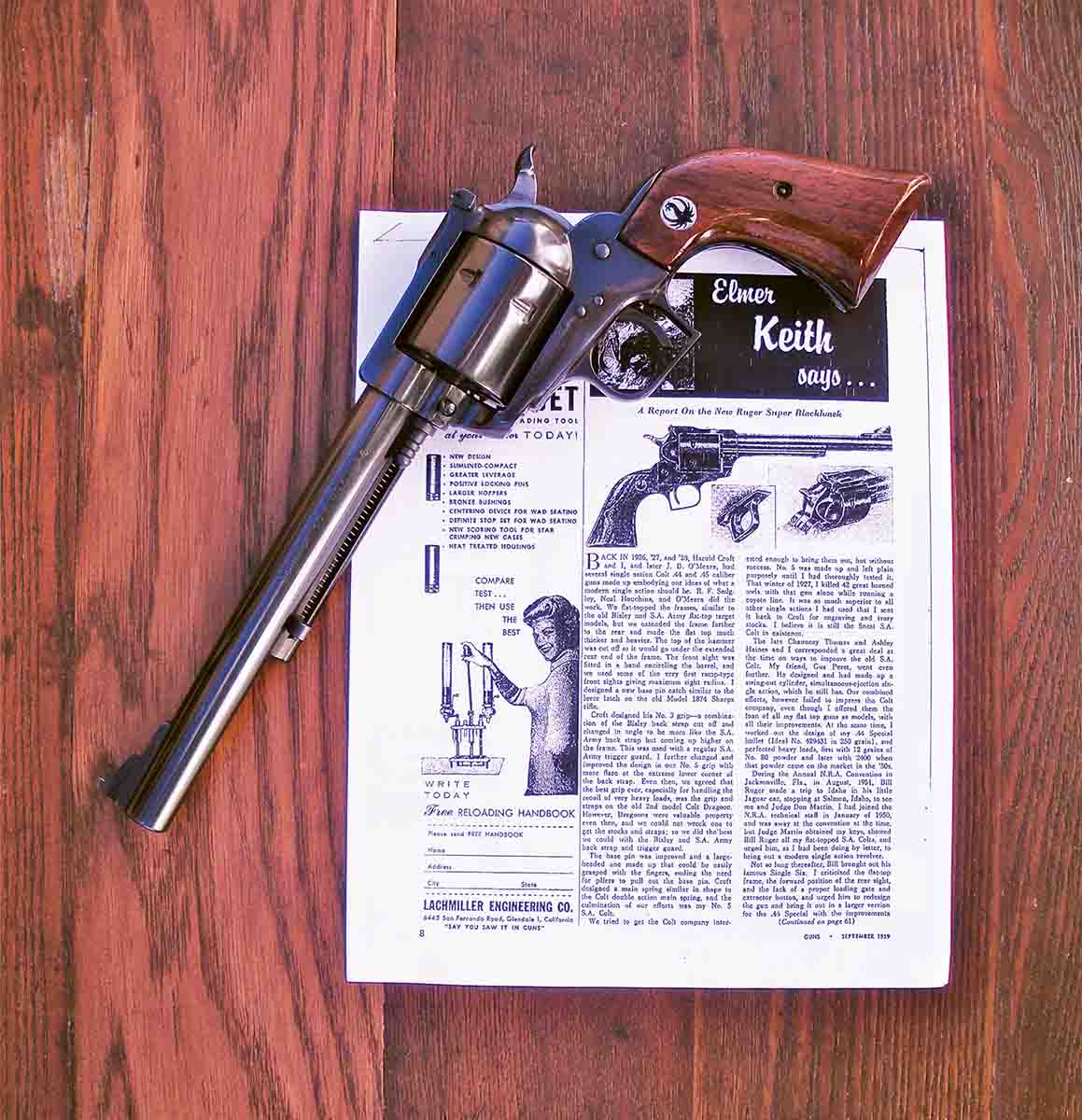

I usually dropped by the mess hall after the long end-of-the-line ride on the school bus and looked at pictures of whatever animals in Outdoor Life, Field & Stream, etc., in the recreation room at one end of the dining hall. In the late 1950s, there was some blather about the world’s most powerful handgun cartridge, the Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum. Some folks claimed it was big enough to kill elk, bears, deer or whatever. By the time all the big words were used up, there wasn’t much left to the imagination.

Somewhere along the line, writers in those back East magazines started in about how the .44 was suitable for bear protection, claiming it was some sort of backup even if you had a high-power hunting rifle, which led me to wonder if folks in New York City or thereabouts, for some reason, didn’t have rifles big enough to shoot bears. Either way, that’s when I learned about being “loaded for bear” with a .44 Magnum, and it wasn’t all unusual for that to be the name of the story.

It didn’t take long before all the writers appeared to be experts in bear protection, recommending some special bullet made by

Eventually I lost interest in the .44 Magnum, .30-30 and even the brand new Remington 7mm Remington Magnum when I decided to go to college, join the U.S. Navy and apply for Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS), the combination of which took care of 10 years away from home and hunting.

Returning to civilian life and regaining an interest in hunting in the 1970s, it didn’t take long to find most outdoor writers were experts on handguns for bear protection. Only once did I read a story, actually a column I think, from a writer who had NOT been attacked by a bear, and lacking any real experience with such matters declined to recommend any handgun for such shenanigans, Charles “Skeeter” Skelton.

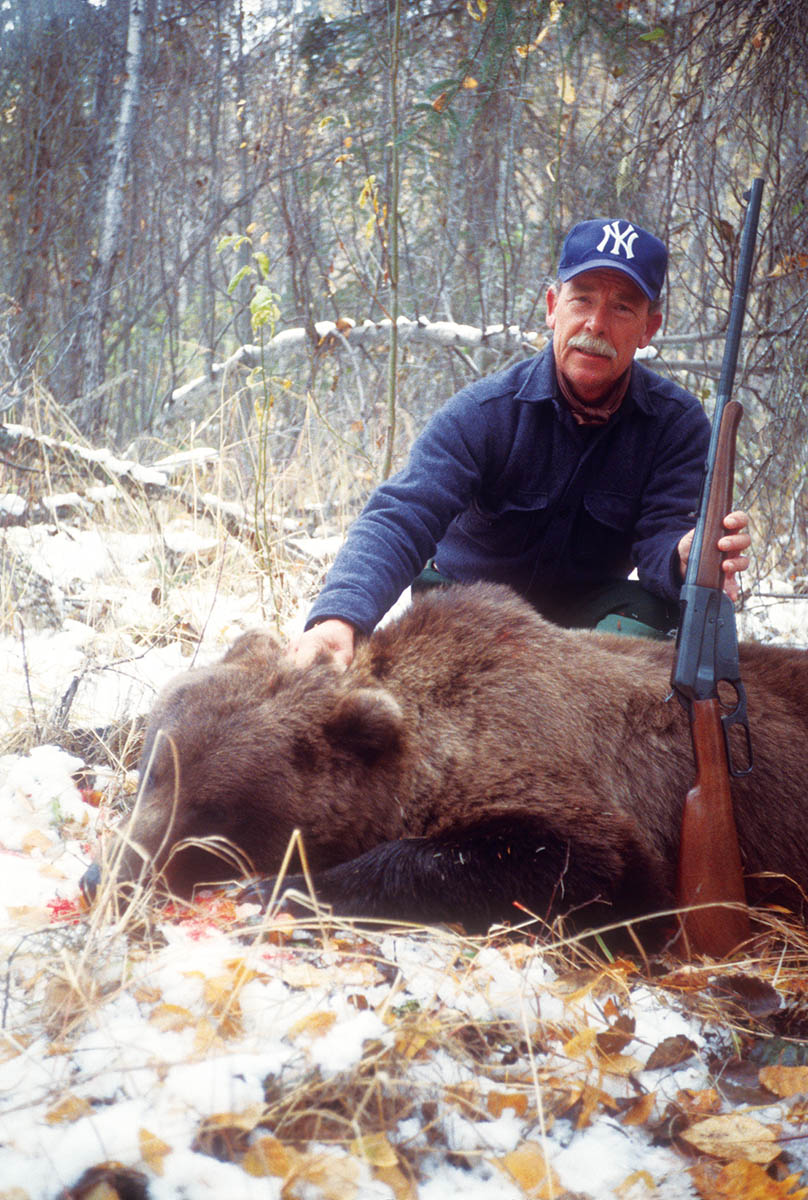

Lots of folks killed bears, of course, but mostly from a stand over foul smelling bait or when the bear was largely unaware of the hunter. If any of those writers had killed a bear in self-defense, they failed to mention it. So if “bear hunting” had anything to do with unexpected “bear attacks,” I missed the connection.

I was jumped by a sow while surveying for a logging road east of Powers, Oregon, in 1964. The incident began when I stepped over a dead fall and came down on the bear’s foot with the heel of my caulk boot. Within a millisecond the brown-colored bear with a cub slapped me across the back as I turned away, tearing my vest and slamming me up against a tree. In retrospect, the tree saved my bacon as I was able to grab it while struggling to stay on my feet. My tin (actually aluminum) hat flew off and when recovered later bore several claw and tooth marks from when it distracted the bear long enough for me to get a few strides ahead of it. After a foot race for maybe 30 yards or so with the bear gaining steadily and breathing on my heels, the cub started bawling and the sow quit the pursuit. The entire episode only lasted a few seconds.

Associates in the industry tell me that I’ve been called a liar by folks, under cover of monikers like Dead Shot or some such, on an Internet chat room for telling that short story in Handloader No. 291 in response to readers who read the feature in Handloader No. 288 (February 2014) by John Havilland regarding potential bear loads in a .357 Magnum.

All I have to say to those who patronize gun/hunting related chat rooms and apparently have no interest in maintaining civil decorum, which I’m told includes at least two would-be gun writers, and can’t pull a sixgun out of a holster and hit what they are aiming at in .5 second or less should take up macrame, knitting or maybe horticulture. Apparently the only shooting these chat room cowboys do is with their mouth, quoting Jack O’Connor.

For those who might be under the false impression that a .44 Magnum, or any other big-bore handgun is going to solve problems with a nasty bear, they should be faster and more accurate with a sixgun, or a five-shooter, than the best whoever lived. That would be Thell Reed and the late Bill Jordan and Ed McGivern among very few others. Short of being able to pull a handgun and shoot accurately in less than .5 second, however, it is best to avoid what amounts to taking a knife to a gun fight with a bear.

For curious folks who might like to know more about the subject of bear attacks in the Lower 48, Alaska or British Columbia, there are several websites with summaries of recorded instances by state and location, and a few list the first known attack, sometimes dating back to the early 1800s. If there is a common conclusion to the thousands of recorded bear attacks over the last 100 years, it would be that the odds of survival are similar to winning the lottery . . . nearly zero.