Shooting the .32-20

Handloads for Modern Revolvers

feature By: Mike Venturino | February, 22

As introduced, bullet weights and diameters for the .38-40 and .44-40 in that order were 180 grains/.400 inch and 200 grains/.425 inch (lead RN/FP bullets). Then consider the .32-20. It was introduced with a .312-inch bullet of 115 grains (lead RN/FP). Most certainly, .32-20 rifles have been used on deer-size game, but by today’s standards, it actually should be considered for animals no larger than coyotes. If there is record of some Old West outlaw or lawman using a .32-20 revolver, never have I encountered such during my lifetime of study. Model 1873 Winchester rifles chambered for .32-20 weighed at least 9 pounds and Colt SAAs were over 3 pounds. A small cartridge chambered in man-size firearms; regardless the .32-20 gained popularity all out of proportion to its power.

At this point, it must be stressed that the accompanying load data should only be used in revolvers made post 1900 and in excellent condition.

Personally speaking, my first .32-20 SAA revolver was acquired in 1979. According to its serial number, it had been made about 1910 and had a 4¾-inch barrel. I must say my experience with that revolver was less than stellar. Firing it from a Lee Pistol Machine Rest, groups mostly ran several inches at 25 yards. Finally, I slugged all six chambers and the barrel. The chamber mouths were uniformly .310 inch but barrel measurement was .314 inch across the grooves. In frustration, that .32-20 was traded or sold, I don’t even remember which.

Except for borrowing a friend’s Colt SAA .32-20 in order to gather some chronograph data, that was the extent of my experience with the cartridge in revolvers. Until late 2020 that is, when I saw advertised for sale one of the 3rd Generation Colt SAAs with a 7½-inch barrel. Its price was attractive because its previous owner had removed the frame’s color case hardening. That wasn’t so attractive but he can be excused. As delivered to him, the frame had surface rust. Removing it removed the case-colors. However, the rest of the revolver is in pristine condition. My idea was to try it out as a shooter. If good, I’d have its frame recolored and case hardened and keep it. If poor, I’d pass it on. Initial shooting was with Black Hills factory loads at 4-inch reactive steel targets placed at 25 yards. That I could hit them regularly even with 71-year-old eyes indicated the Colt is a fine shooter.

Or had I? RCBS Cowboy dies sat right on the shelf above my reloading bench. My .313-inch lube/sizing die was in its box with about 50 others. Preliminary shooting had given me a few dozen .32-20 Starline cases for starters. But, where were my bullet moulds? I knew without doubt that there were four on hand: a Lyman 311316 (115 grain, gas check, FN), a Lyman 311316HP (same but hollowpoint) – both of those are now discontinued. Also, I had a Lyman 311008 (115 FP) and an RCBS 32-98-SWC (98 grain SWC). Only the hollowpoint mould remained. Where the others went, I have no memory. (As a COVID-19 survivor, perhaps that memory disappeared along with my senses of taste and smell?)

So the hunt began. A Lyman 311008 mould would have been simple as a friend has one, but I decided on adventure. A recently acquired .41 Long Colt mould bought from MP Molds in Slovenia has been a gem. Its website cataloged a “convertible” mould dropping flatpoints of .314 inch. By convertible, I mean that by a pin and plug arrangement, the mould could produce solid or hollowpoint bullets. Ordered was one made of brass with four cavities. For my first session, two cavities were set as hollowpoints and two for solids. Of 1-20 tin-to-lead alloy, their weights were 115 and 120 grains in the same order.

RCBS mould 32-98-SWC had produced bullets giving fine accuracy from a formerly-owned S&W Model 16 K-32. However, it seemed that no sources found on the internet had such moulds in stock. Again, I decided to gamble. On the internet was a Utah-based bullet mould making company named Arsenal Molds. Among many designs, they cataloged one as a clone to RCBS .32-98 SWC. It was also available in brass with four cavities. From it, my bullets drop at 100 grains of 1:20 alloy. Added to my home cast bullets were 115-grain flatpoints by Oregon Trail and powder-coated 115-grain flatpoints from Missouri Bullet Company. My bullets were sized .313 inch and lubed with DGL. Oregon Trail’s bullets were sized .314 inch and lubed with its own hard lube. MBC’s bullets, of course, needed no lube and were .313 inch in diameter.

However, another factor with this particular revolver came to light. Its firing pin often punched through pistol primers. It did not always happen, but enough to be a concern, for it is possible for gas to escape from punched primers to erode the firing pin. Therefore, some CCI 400 Small Rifle primers were substituted toward the end of this project with a few of the most promising component combinations. As the table shows, they increased velocity with one load, but stayed about the same as small pistol primer velocities with two others. None punched through. To save wear on this revolver, most likely all my future handloads will have small rifle primers.

Suitable powders for the .32-20 mostly run from Bullseye to Unique, but the Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook 4th Edition even lists Accurate 5744 for 100- and 115-grain bullets. That same manual lists Titegroup and W-231 as prime choices for 100- and 115-grain bullets, respectively. To those were added old favorites, Bullseye and Unique. Of course, A-5744 is my favorite cast bullet powder, so it was tried briefly. It did not increase velocities and gave too much unburned powder to be feasible.

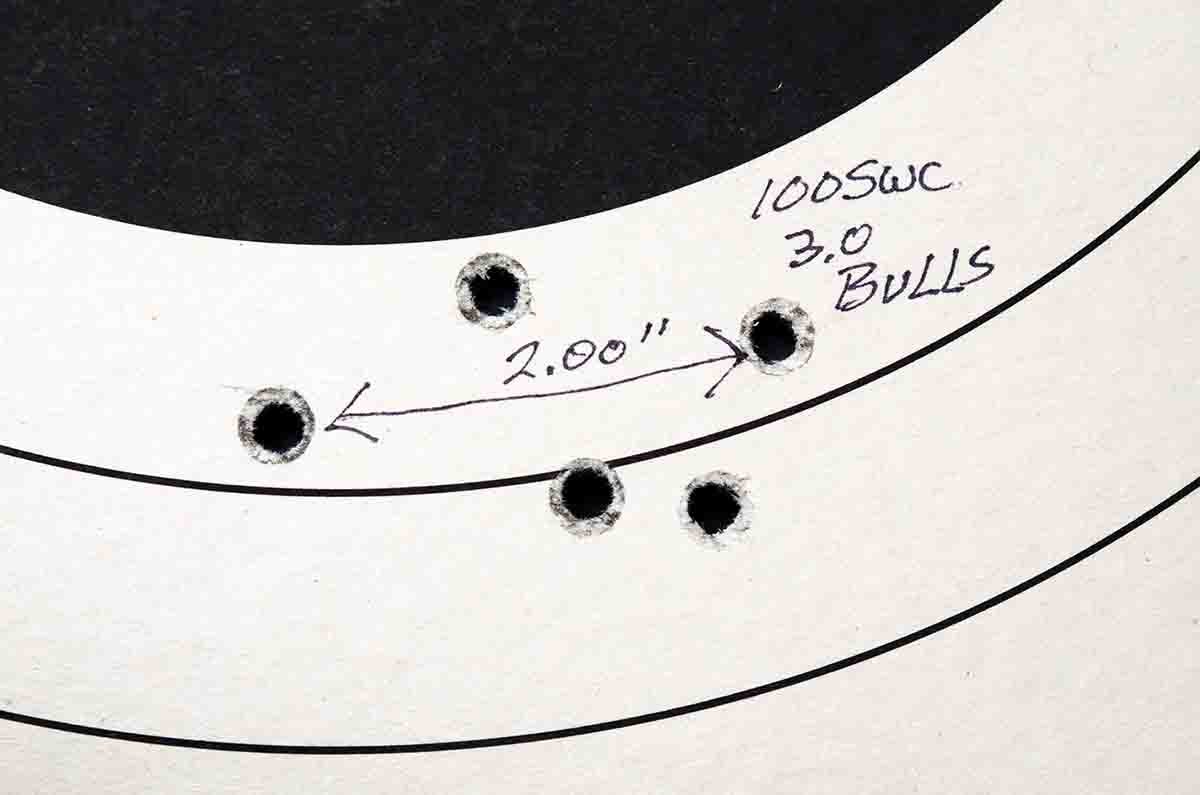

All in all, I consider Titegroup in a charge of 3.5 grains to be a best overall .32-20 propellant. Groups with it under any of the bullets were nice and round, ranging in the 2-inch range and smaller. Shooting was done over sandbags instead of using my Ransom Pistol Machine Rest for several reasons. So, flyers from otherwise very tight three or four shot clusters were likely shooter error. A nice, gentle .32-20 load with noise and recoil almost akin to .22 LR revolvers was the 100-grain Arsenal SWC over 3 grains of Bullseye. Of course, the great weight of this revolver accounts for such gentle recoil. For those who might desire the highest velocity, then 4 grains of Unique broke 1,025 feet per second (fps) with 100-grain bullets and 3.7 grains with the 115- and 120-grain bullets broke 1,000 fps by just a mite.

DGL lube and Arsenal Molds deserve a few words of praise here. This was my first use of this lubricant in revolvers, and cleaning the big Colt .32-20 after more than 100 rounds revealed not a single trace of lead in the barrel or chambers. What powder fouling was in the Colt’s barrel was soft and wiped clean with a single patch of bore cleaner. Arsenal Molds’ four-cavity brass “RCBS 32-98-SWC” clone was of fine quality. Its bullets were round and of consistent weight from cavity to cavity. No wonder they shot very well. That 100-grain SWC and the 120-grain MP Molds solid will be my mainstays from here on. Casting both with four-cavity moulds in tandem will produce a pile of bullets in a short time.

Admittedly, I had some reservations on getting back into .32-20 handloading again; I wondered at myself for spending money on another .32-20 sixgun. I’m happy to say that all those reservations are gone. True, it doesn’t fling my steel practice targets about such as the larger SAA cartridges do when hit by one of my other single actions. That said, the gentle shooting it affords helps with the hitting part.

.jpg)