What’s in a Name

In the Case of the.250-3000, Too Much

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 23

Carmichel noted in a book that the “fastest” he’d ever seen a bull elk drop at one shot was with a .250-3000 and numerous accounts from the 1920s onward carry similar claims. These were often countered, however, by tales of animals being hit and escaping, or of bullets blowing up on impact, or rifles failing to deliver decent accuracy.

What this boils down to is that the .250-3000 (more commonly, and more accurately, known today as the .250 Savage) is a handloader’s cartridge, and not just because factory loads are now very hard to come by. More than any other cartridge introduced in the last 100 years, it needs the fine touch of a handloader to perform up to its potential.

The foremost designer in the U.S. was Charles Newton. He had already created the .22 High Power for the Savage company, which was eagerly grabbing anything that would give them an edge over older, established companies such as Winchester and Remington.

Newton took the .30-06 case, shortened it, and necked it down to .257. He recommended it be loaded with a 100-grain bullet for big game, but the marketing people at Savage wanted a cartridge that would deliver 3,000 fps. With an 87-grain bullet, the .250 would do that, so that became the original loading and source of the name “.250-3000.”

First, the .250 was designed specifically to fit into the Savage Model 1899 action, which limited its allowable overall cartridge length. The 99’s rotary magazine would accept a cartridge only 2.5 inches long. With an 87-grain bullet, and the powders then available, this could deliver the necessary velocity, but only barely. Also, when the cartridge was introduced, the standard barrel length was 24 inches, but the factory would accept custom orders for barrels anywhere from 18 to 28 inches. The longer barrels allowed full combustion (for lack of a better term) while the shorter ones usually did not.

Around 1922, Savage began offering two variations on its .250-3000, the Models ‘E’ and ‘F.’ The Model F was a takedown, while the E was, to my mind, the almost perfect woods rifle, with a straight grip, Schnabel forend, and 22-inch barrel. It was designed for quickness. Fitted with a Lyman receiver sight, it was the ideal rifle for deer out to 250 yards; it carried easily in the hand, essential for snap-shooting in deep-woods situations, or getting on a deer in a mountain meadow before it melts into the timber.

Through the 1920s, the Savage 99 in .250-3000 was the rifle for the cognoscenti. I remember seeing deer-camp photos from that era, with deer on meat poles and hunters gathered around. In one, there were easily two dozen deer hanging up, with a dozen hunters around, and everyone was holding a 99.

The stories notwithstanding – and there were books written about carrying a .250-3000 across Asia and shooting tigers, among other things – it’s safe to say most of these guys were not getting the ballistic performance they thought they were. This was before riflescopes became common, and long before personal chronographs, and standards of accuracy were different. A 3-inch, five-shot group at 100 yards was excellent accuracy, and one article about lever rifles in Gun Digest in the 1960s even suggested anything up to 4 inches was okay. Shooting with open sights, most of us would be happy with that.

In 1915, Savage settled on a twist of 1:14 for the .250-3000. Remember, in those days, riflemakers worried about “over stabilizing” bullets with a too-tight twist, whereas today, we don’t. When they reduced barrel length to 22 inches, they stuck with this twist. Whether factory ammunition with 87-grain bullets worked well in those, I can’t say, but for sure when they started loading 100-grain bullets, with nominal velocities well below 3,000 fps, they certainly did not.

With an 87- or 90-grain bullet, shooters need at least 2,850 fps to stabilize with a 1:14 twist. This can be achieved, but with a short barrel, a fast-burning powder such as IMR-3031 is needed, not 4350.

Even with an 87-grain bullet, it requires considerable effort to get the necessary velocity from a 22-inch barrel.

Another factor we have not considered is bullet construction. I don’t have any 87-grain Savage bullets from 1922, but I do know a little about modern 87-grain .257s. Most are intended as varmint bullets that expand rapidly on even small animals like woodchucks. At higher velocities, these are most emphatically not big-game bullets. I suspect an 87-grain bullet in 1922 had pretty light construction. Hit an animal exactly right and it might drop like a stone, but hit a few inches off, and you get a terrible surface wound and an animal that runs off and dies a lingering death. Hence, the conflicting stories from the 1920s.

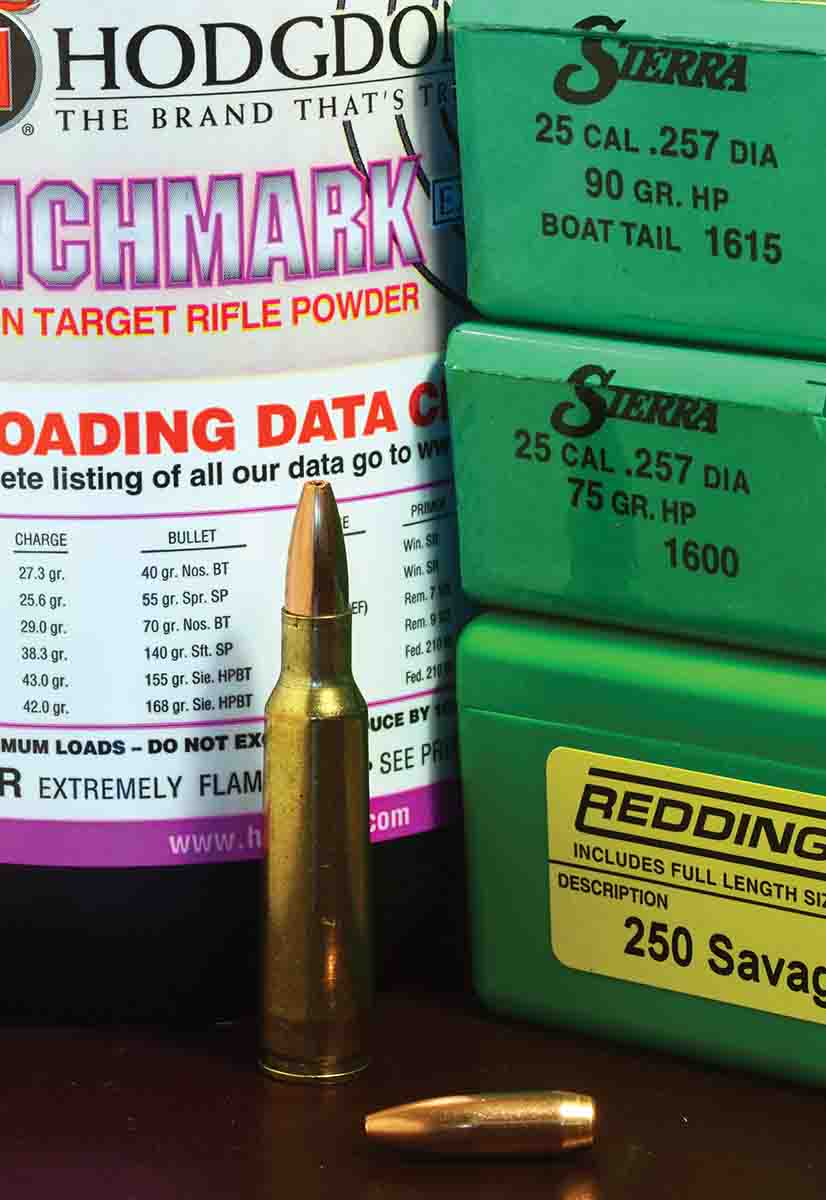

There are two modern bullet exceptions I know about. One is Sierra’s 90-grain hollowpoint, which, I was told, was intended primarily as a big-game bullet. Its hollow point shortens it slightly from a spitzer, helping to solve both the length problem and the powder capacity problem. The other is Speer’s 87-grain Hot-Cor spitzer, which is recommended for “medium” game.

In my Model E, the Sierra works particularly well, and it’s the one I have done the most work with. I have not hunted with the Speer.

Eight years ago, I acquired something I had wanted for a long time; a .250-3000 chambered in a Mauser-actioned rifle, with a 24-inch barrel and a 1:10 twist. Obviously, this solves all the problems, and it handles 100-grain Nosler Partitions or Ballistic Tips like a dream. With modern powders and some extra allowable cartridge length, it even approaches 3,000 fps with a 100-grain bullet. Similar custom rifles could have been made in the 1920s, and probably were, but after the .270 Winchester was introduced in 1925, why would you?

Back to the 99E. The load table (on page 47) gives the combinations I’ve tried with the Speer bullet. Incidentally, the Sierra 90-grain bullet is listed as out of stock as I write this, but the Speer 87-grain Hot-Cor spitzer seems to be readily available.

I particularly wanted to try some of the newer powders, including those from Shooters World and Vihtavuori, but neither had any loading data available. This is not surprising. Compiling data with pressure barrels is no small undertaking, and since the .250 Savage has been listed as obsolete as far back as the 1969 Lyman handbook (No. 45), it’s no wonder they omitted it.

As listed in the Hodgdon data, these were all maximum loads, but not one exhibited even the most minor sign of high pressure. The primers were perfect, extraction effortless and the cases barely expanded above the web. This leaves considerable room for tuning loads to get the optimum combination of velocity and accuracy.

Since most of the .250 Savage’s accuracy problems can be traced back to overall length, velocity, and twist rate, the question arises, what would be the ideal twist rate? There are several ways of calculating this. A couple of manufacturers offer online programs where you simply enter your data to get the optimum twist, but my experience with these has been spotty.

In the 1960s, Gun Digest published a graph with a formula for calculating twist and I’ve found this to be the most reliable for my purposes. The program on the Berger website is probably too sophisticated for simpler questions such as the twist rate in my century-old 99, but it gives a reasonable idea. If one Googles “calculating rifle twist rate,” several formulas come up that were not around a decade ago. Some insist on specific gravity, others differentiate between bullets with and without boat-tails, or want to know the temperature and altitude. This is fine if you’re a sniper hoping to hit a target a mile away in the mountains, but that is a little exotic for most practical purposes.

They all seem to agree, however, that the minimum velocity to stabilize the Sierra 90-grain in a rifle with a 1:14 twist is 2,850 fps. Short of rebarreling, twist rate is not something we can vary, so obviously the goal is to get to 2,850 fps, and 2,900 would definitely be better.

And the .250 Savage’s iconic (if mostly imaginary) 3,000 fps? Better still – if you can do it.

In the 1960s, Savage discontinued, and then reintroduced, the .250, and chambered it in a different rifle, although it was still called the 99E. Very confusing. They gave it a 1:12 twist, which made things somewhat easier for everyone, but the rifle was short-lived.

An obvious question is, why should we care? Why fool with a cartridge that is 108 years old when we have so many modern cartridges and rifles to choose from? The answer is, I don’t know of a modern rifle that offers everything my 99E does, ballistically, in a package that is such a pleasure to carry and shoot.

.jpg)