38 Super Automatic +P Loads

A Tried-and-True Kimber 1911 Stainless II

feature By: Patrick Meitin | July, 25

You don’t hear as much about the 38 Super Automatic today as you once did, with only a handful of manufacturers offering pistols chambered for this excellent pistol round. This is a shame, as the 38 Super really has a lot to offer. Providing a clear ballistic advantage over the more popular 9mm Luger and even venerable rounds such as the 45 ACP. The 38 Super is nothing new, it was developed in 1929 by John Browning for the Colt Model 1911. It is essentially the 38 Automatic (introduced in 1900 and one of the first commercially successful semiautomatic pistol cartridges) loaded to higher pressures. This is why you’ll commonly see a +P added to case headstamps, though that development didn’t appear officially until 1974. The +P designation was added to distinguish it from the lower-pressure 38 ACP.

Regarding power, the 38 Super sits squarely between the 357 SIG and 357 Magnum, making it a solid self-defense or light-game option. Aside from some cult-like followers, it has more recently become most popular with USPSA and IPSC shooters (U.S. Practical Shooting Association and International Practical Shooting Confederation), where a combination of flat trajectory, light recoil allowing faster recovery and an enhanced degree of energy delivery hits a sweet spot balance for those shooting disciplines.

The semi-rimmed 38 Super includes a slightly larger head diameter than the 9mm Luger (.406 versus .394 inch) and is .900-inch long (trim-to length .890-inch), compared to the 9mm’s maximum .754-inch length (.749-inch trim-to). Both cartridges share the .050-inch rim thickness. The 38 Super holds 18 grains of water, on average, compared to 14.5 grains for the 9mm Luger. Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) is 36,500 pounds per square inch (psi) for the 38 Super, and 35,000 psi for the 9mm Luger. This gives the 38 Super around 20 percent more muzzle energy than the 9mm Luger while shooting 124-grain bullets, translating into about 200 fps additional velocity. In most instances, the 38 Super provides greater muzzle energy than standard 45 ACP factory loads. The only downside to all of this is that the 38 Super is too long for 9mm/40 S&W pistol frames, requiring larger 45 Auto framed handguns to function.

Initially, the 38 Super Auto lived in the shadow of the 45 ACP, but it eventually became popular in places where NATO cartridges were not allowed. This was most notable in Latin American countries. Though those laws were evidently rescinded, the Latin American popularity remained. The Latin propensity for bright and flashy, I guess, explains why so many 38 Super handguns include mirror-like finishes and garish ivory grips, with some even holding inscriptions of Catholic saints, skulls, the Mexican flag and similar themes.

On the American market, the 38 Super may have faded away completely had it not been discovered by a cadre of practical combat pistol shooters who found it ideal for that type of competition. It exceeds the power-factor threshold to meet “major” classification guidelines geared to specifically eliminate the 9mm Luger. Currently, 38 Super pistols are available through EAA Corp/Girsan, Tisas, Dan Wesson, Colt, Rock Island, Les Baer, Wilson Combat and the Kimber 1911 Stainless II used for testing here.

Due to the waning U.S. popularity of the 38 Super, factory ammunition prices have spiked dramatically, when you can find it at all. Most 38 Super factory loads are target fodder, not dedicated hunting (Colt marketed the 38 Super as a hunting round as late as 1940) or self-defense options. This makes it an obvious handloader’s cartridge, as manufacturers such as Starline (used for this test) supply top-quality brass, and the 9mm bullets it feeds on are ultra-abundant. I was able to run 115-grain bullets up to 1,600 fps, 124-grain bullets up to 1,550 fps and 147-grain bullets to about 1,350 fps from a 5-inch barrel.

Interestingly, original 38 Super pistols were generally noted for poor accuracy, as the thin rim proved inadequate for headspacing and often caused ignition issues. Later, 38 Super chambers were redesigned to headspace off the case mouth, based on the work of Irv Stone of Bar-Sto Precision Machine barrels. This immediately solved the cartridge’s shortcomings and transformed it into a round synonymous with accuracy. Like other autoloading pistol cartridges that headspace off the case mouth, a light taper crimp is used not only for proper headspacing but to hold bullets securely during recoil and to provide thorough powder ignition. During loading, I first seated bullets, and then returned to apply the taper crimp as a final step after removing the seating stem. Overall loaded lengths (OAL) of 1.175 to no more than 1.275 inches are recommended, and like other autoloading rounds, seating bullets too deeply has the potential to introduce pressure spikes. Maximum accuracy is maintained through consistent case length, .890-inch again the preferred trim-to length.

Kimber’s Stainless II was used as the test vehicle, a full-sized 1911 measuring 8.7x5.25x1.28 inches and weighing 38 ounces empty. In the 38 Super, the magazine holds nine rounds, and the pistol includes a full-length guide rod and a 16-pound recoil spring. In classic 38 Super fashion, the frame is highly polished stainless steel with “bonded ivory” grips. It also includes a smooth, polished front strap and checker-cut backstrap that provides a firm grip while shooting. The slide includes matching high-polish stainless steel and front serrations. The match-grade steel barrel is 5 inches long and held by a match-grade stainless steel bushing. It includes a left-handed 1:16 rifling twist. The iron sights include front and rear white dots for positive alignment and high visibility. The aluminum trigger is a three-hole match grade design that arrives from the factory with a crisp 4- to 5-pound pull. This pistol retails for around $1,223. As a consummate 1911 fan, I give the test pistol an enthusiastic thumbs up. The overall look is just a touch kitschy for my taste, though the Kimber design comes across as more low-maintenance practical than flashy.

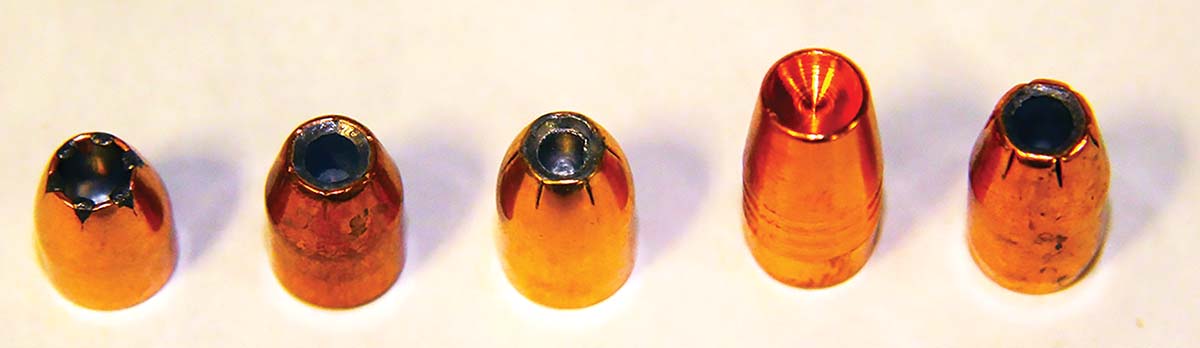

The Hammer Bullets .730-inch, 137-grain nontoxic/pure-copper Jack Hammer was engineered to provide outstanding terminal performance with 100 percent weight retention. It includes a cupped nose that ensures deep, straight-line penetration and devastating soft tissue damage. The Hammer provided reliable feeding in the test pistol, the company recommending a minimum 1:23 twist rate, which was amply compatible in our case. Hammer rates this bullet for hunting as well as personal defense. Like all 100 percent copper bullets, the Jack Hammer is long for the weight, especially at 137 grains. Accordingly, powders were chosen for low bulk density to avoid severely compressed loads that have a frustrating habit of initiating creeping bullet “spring-back” and resulting feeding issues.

Hornady’s excellent XTP jacketed hollowpoint represented the 147-grain slot. XTP stands for eXtreme Terminal Performance, and was designed for hunting, self-defense and law enforcement, while providing enough accuracy for competitive shooters. They were engineered to expand reliably at a wide range of handgun velocities and drive deep via a controlled expansion design. The jacket protects the bullet nose for reliable feeding.

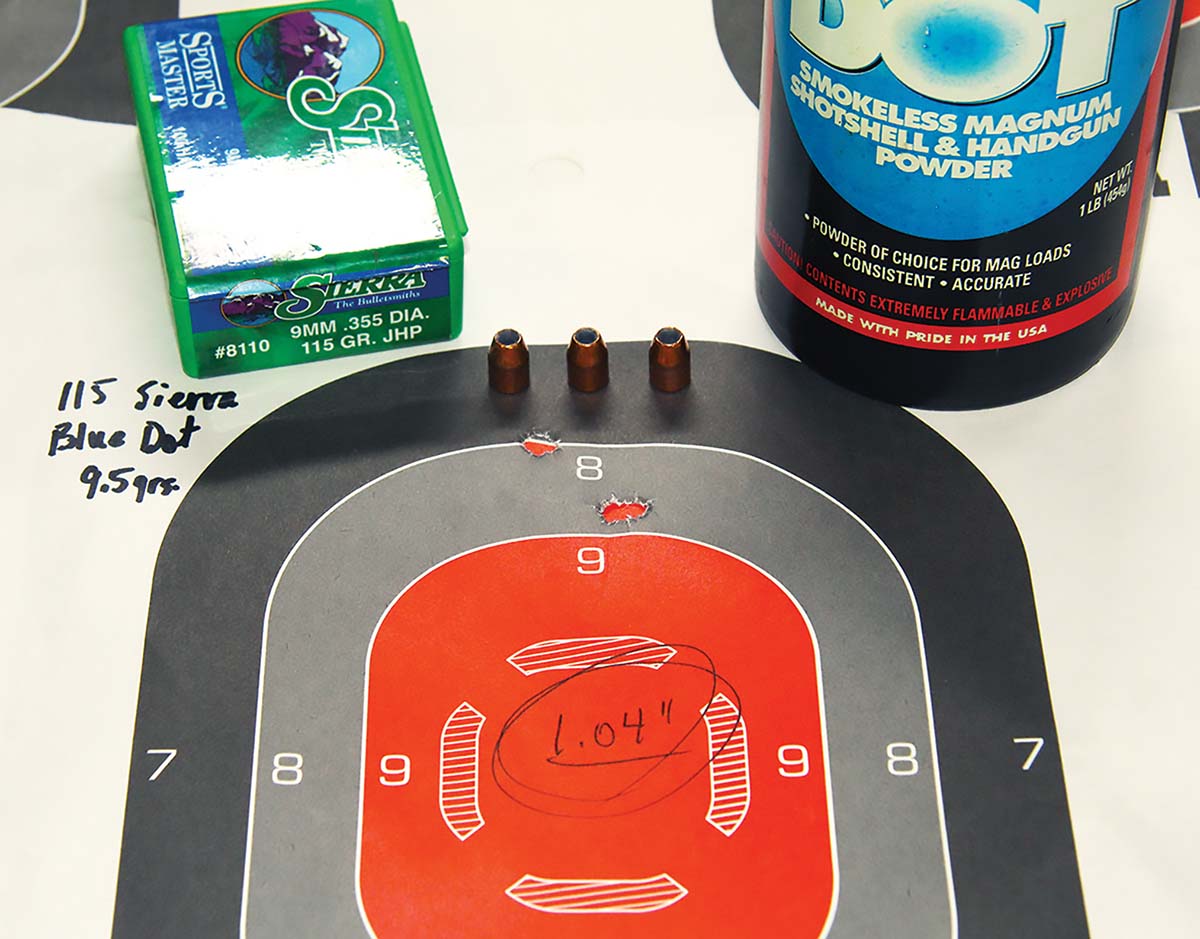

Finally receiving a break in the early spring weather, I ventured forth to slop in the mud and get some shooting done. Shooting was conducted from atop an MTM Case-Gard Predator Shooting Rest with the rear section removed to make use of the padded wrist rest. This rest was set on a heavy portable bench. Many of the largest groups were caused by single fliers that I take responsibility for, but were recorded as shot. Recoil did not become noticeable until reaching the 147-grain mark, but even those loads were quite manageable. The Kimber consumed all of the listed loads off the magazine without a single hiccup.

I see huge potential in the 38 Super while shooting 147-grain slugs as potent hog medicine. For comparison, while the 10mm Auto with 180-grain bullet sent at 1,250 fps delivers 624 foot pounds of kinetic energy off the muzzle and 432 foot pounds at 100 yards, the 38 Super with 147-grain bullets leaving the muzzle at 1,350 fps produces 595 foot pounds of energy point blank and 423 foot pounds at 100 yards – which I would call close enough.