From the Bench

Return of the Grizzly

column By: Art Merrill | July, 25

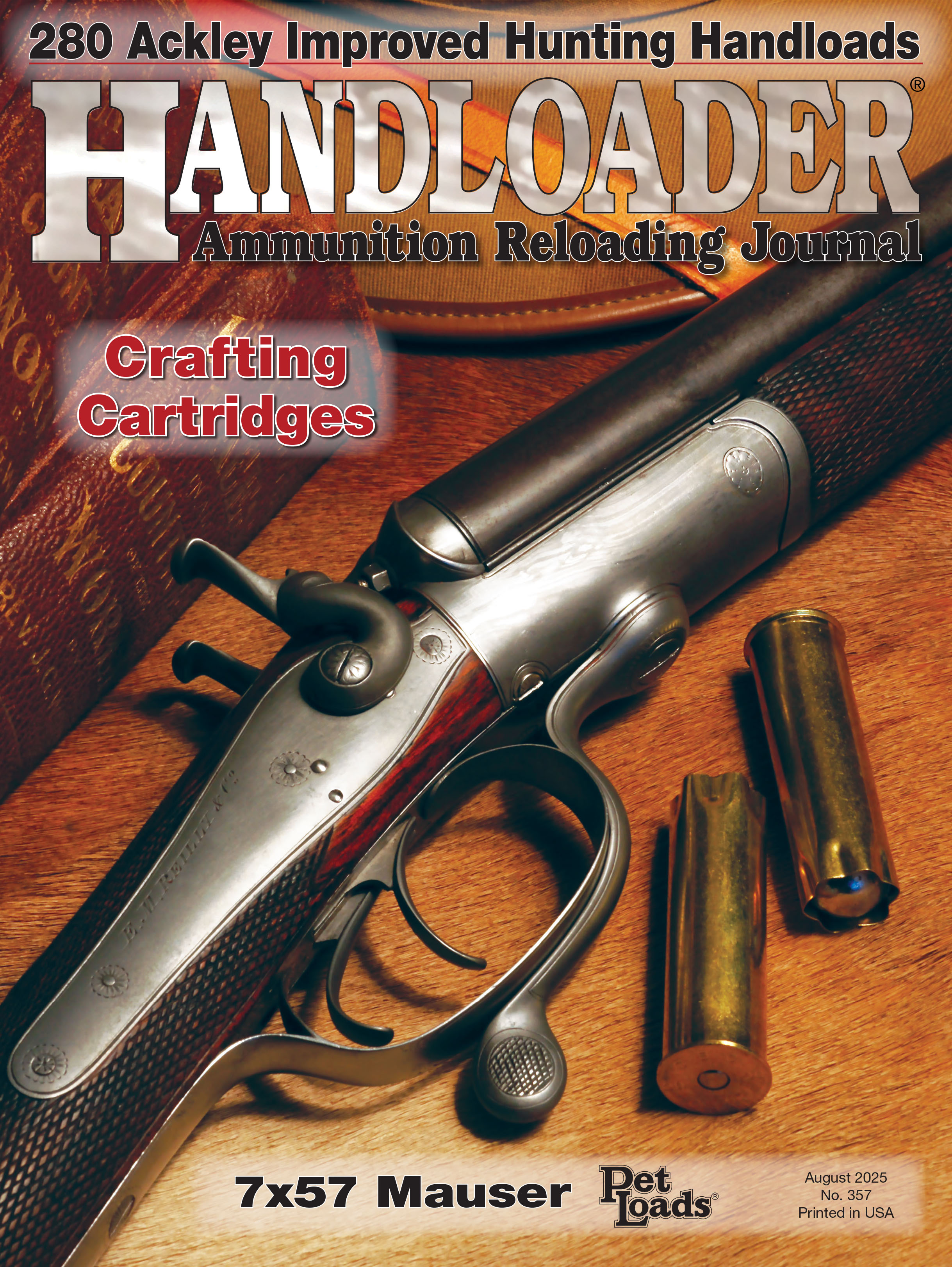

Colt has reintroduced the Grizzly 357 Magnum revolver after a hiatus of 30 years. The Grizzly’s first incarnation was a Colt Custom Shop 357 Magnum, mating a Python barrel to a King Cobra frame. Colt produced only 999 of these revolvers during 1994-1995. These Grizzly revolvers featured a Magna-ported six-inch barrel, a non-fluted cylinder, Pachmyr grips and a matte stainless finish. Today, minty original Grizzlies can fetch $4,000 and more.

Colt’s 21st Century Grizzly is all Python, a 44 Magnum revolver chambered in 357 Magnum. That Colt has an MSRP of $1,600, about the same as a used first-generation Grizzly in “shooter condition.” Upon picking it up, the new Grizzly feels good in the hand. It is well balanced by the 4 1⁄4-inch barrel – an appropriate length on a general-purpose revolver that might be utilized for self-defense, hunting or informal target shooting. The grip fits my medium-sized hand, neither too narrow nor too wide. Though Colt literature describes the new Grizzly’s stainless-steel finish as “brushed,” it has the appearance of a bright polish rather than the matte of a brushed finish.

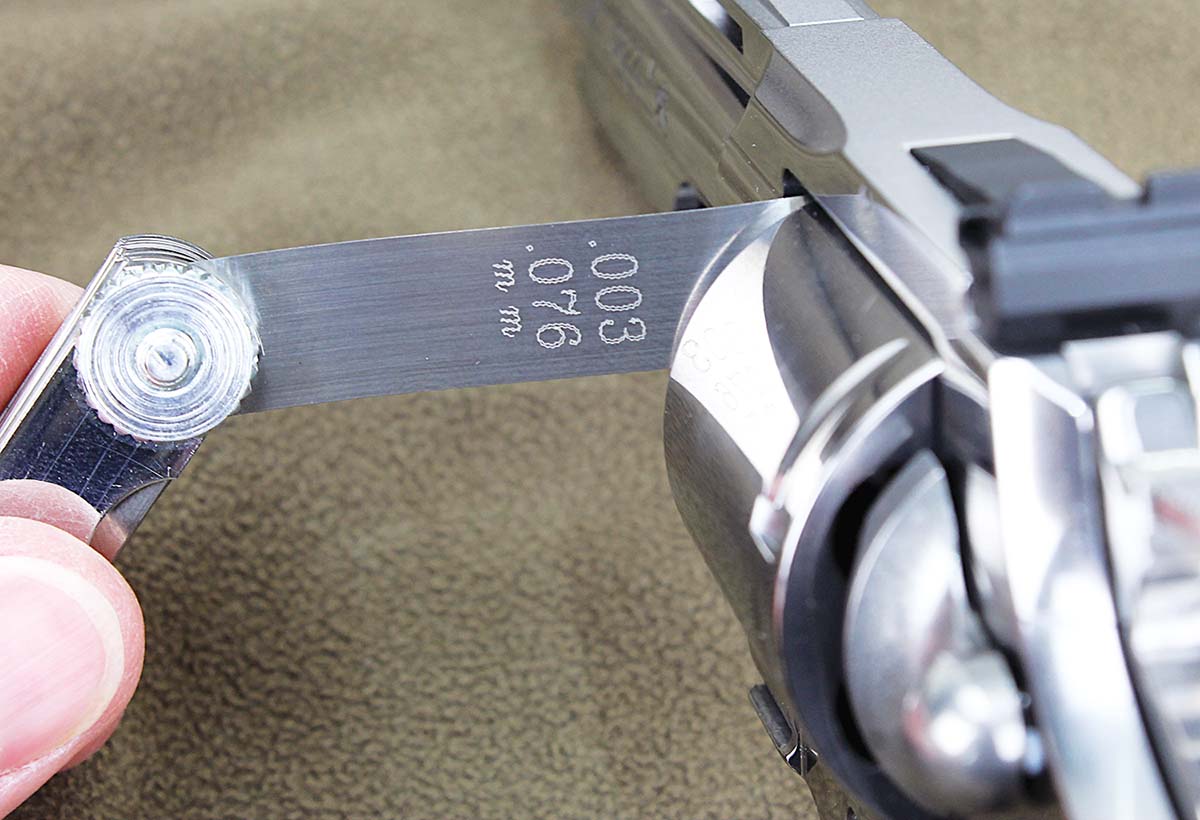

Hammer-cocking a DA/SA revolver for single-action shooting renders better accuracy via a steadier hold, so it’s always preferred whenever possible. This Grizzly’s SA trigger breaks between 51⁄2 and 6 pounds with almost indiscernible creep that is probably measured in microns. So little, in fact, that you would never notice it unless you were deliberately looking for it. The trigger face, cylinder latch and hammer thumbpiece are all grooved to resist finger and thumb slippage.

Several Grizzly features aid in reducing the recoil of the 357 Magnum cartridge. First and most apparent, again, is pairing the smaller cartridge with the larger Python 44 Magnum frame. Then there are the six barrel ports, three on each side of the front sight. The full-length shroud for the ejector rod, the vent rib on top, and the unfluted cylinder all contribute some beef to the overall 42-ounce weight that helps absorb recoil. The synthetic Hogue grip prevents the trigger guard from bashing into the middle finger knuckle during recoil. However, the grip’s open backside places the stainless steel backstrap directly against the shooter’s hand, so the Hogue provides no cushion from the backward thrust of the revolver. However, the Hogue’s width, texture and slight flair at the bottom are aids in controlling the recoiling revolver.

If you don’t like the red insert front sight, it can be easily replaced. Colt offers fiber optic, tritium and brass bead options. Replacement requires only a .050 Allen wrench to turn the 4-40 set screw. The rear sight is adjustable for windage and elevation, as befits a revolver capable of digesting two different cartridges and a large variety of bullet weights, utilizing that same .050 Allen wrench.

Certainly, the 357 Magnum and 38 Special cartridges need no introduction here; probably most of us cut our handloading teeth on the 38 Special. To offer a lesser-known factoid, the 357 Magnum is the progeny of the short-run 38-44 Special cartridge of 1930, which was a souped-up 38 Special significantly powerful enough to be intended only for Smith & Wesson’s big N frame Heavy Duty and Outdoorsman 44 Special revolvers, fitted with an appropriate .357-inch bore barrel. How powerful? The 38-44 launched a 158-grain bullet at about 1,150 feet per second (fps), pretty much the same as modern 357 Magnum factory loads. Concern over someone inadvertently (or boneheadedly) shooting the 38-44 in weaker 38 Special revolvers is partly the reason the 357 Magnum (with its .135-inch longer case deliberately intended to not fit 38 Special chambers) made its appearance five years later, thanks to development work done by Phil Sharpe. To illustrate the hazard, SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) MAP (Maximum Average Pressure) for the 38 Special is 17,000 pounds per square inch (psi); 357 Magnum MAP is more than twice that, at 35,000 psi.

Even with those heavy bullets stepping out of that short barrel at around 1,100 fps, the Grizzly’s recoil was easily manageable, which apparently is the whole point of the Grizzly. Bullet holes in the target paper showed the Grizzly’s fast twist does, indeed, stabilize the heavyweights, and group sizes showed the revolver has accuracy potential further out. Certainly more than enough for self-defense.

Colt’s new Grizzly has a lot going for it, including good looks and that indefinable pride-of-ownership aura that comes with exceptional quality. If you’re looking for an all-around revolver with plenty of bark that won’t bite the hand that feeds it, check out the Grizzly.

.jpg)