Some folks may think it a bit odd to find the history of a rimfire cartridge in this column. Instead, they would prefer to learn about centerfire cartridges. These are the types that have a recess in their base to house little, largely unobtainable items called primers – one hundred of which now cost almost as much as the same number of cheap imported 22 Long Rifle (22 LR) cartridges.

Cartridges: (1) 22 Short and (2) 22 Long with their 29-grain bullets, the (3) 22 LR with its 40-grain bullet that is the same as was loaded in the (4) 22 Extra Long.

At any rate, virtually all of us were introduced to shooting by a firearm chambered for the 22 LR. It was not, however, always this way. Modern rimfire history begins in 1857 with Smith & Wesson’s No. 1 pistol cartridge, later known as the 22 Short. By 1860, Frank Wesson (Daniel Wesson’s brother) was chambering single-shot pistols and target rifles for the No. 1 cartridge. Target rifles? Yes, the appearance of self-contained cartridges caused target shooting in the U.S. to become very popular. Shooting was done standing in German Schutzen style, using heavy, long-barreled rifles. In winter, shooters went indoors. Seventy-five feet (25 yards) was standard range, though some were as short as 50 feet. The only cartridge suitable was the 22 Short, and in black-powder form, acceptable accuracy could not be obtained past the longer distance. Also, bullets sometimes stuck in the long target barrels.

What to do?

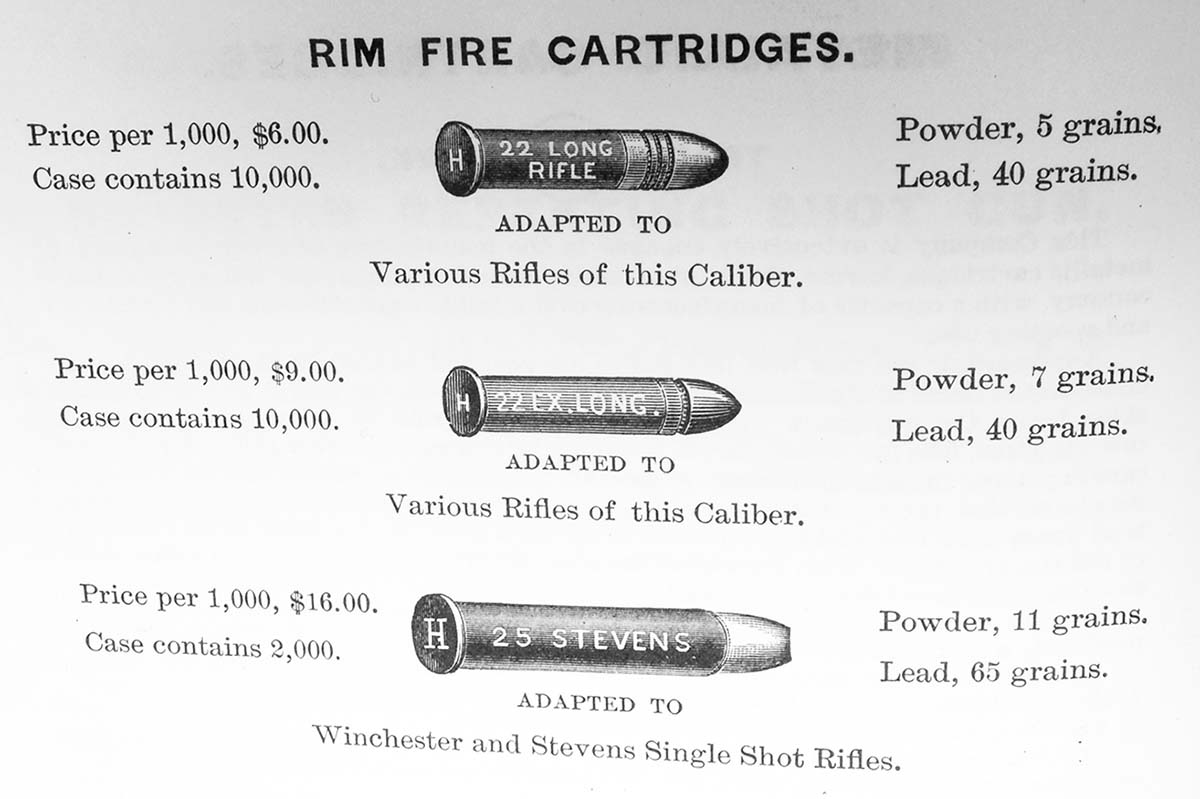

Obviously, more velocity was necessary. This required more powder in a longer case. New case lengths and powder charges varied, but the 29-grain 22 Short bullet remained. The case eventually became about .595-inch containing 5 grains of powder (bulk measure) as opposed to the 22 Short’s 3 grains. Retaining the short, light bullet was necessary because competitors wanted to simply rechamber their slow-twist 22 Short rifles rather than rebarrel. The round was called the 22 Long. By 1868, Frank Wesson was offering target rifles so-chambered. The first official notice of the cartridge seems to be the Union Metallic Cartridge Co. list of 1871.

The 1900-period 22 LR chambered rifles are (top to bottom), Remington No. 6, Stevens Favorite and Winchester Model 02A.

Remember that this was before the existence of smokeless powder. The 22 Long’s greater powder charge meant its 29-grain bullet had more fouling to run over in its trip up the barrel. Competitors found the 22 Long to be not as accurate at 50 feet as the 22 Short, about the same at 75 feet, in gallery shooting. At 50 yards, the 22 Long may have held an edge over the 22 Short. Its higher velocity (probably about 700-800 fps) made it superior to the 22 Short for small-game hunting. An interesting aside was discovered in the writings of one George Wentworth. He was a rather well-known contestant in 200-yard centerfire and 22 rimfire gallery matches, winning many.

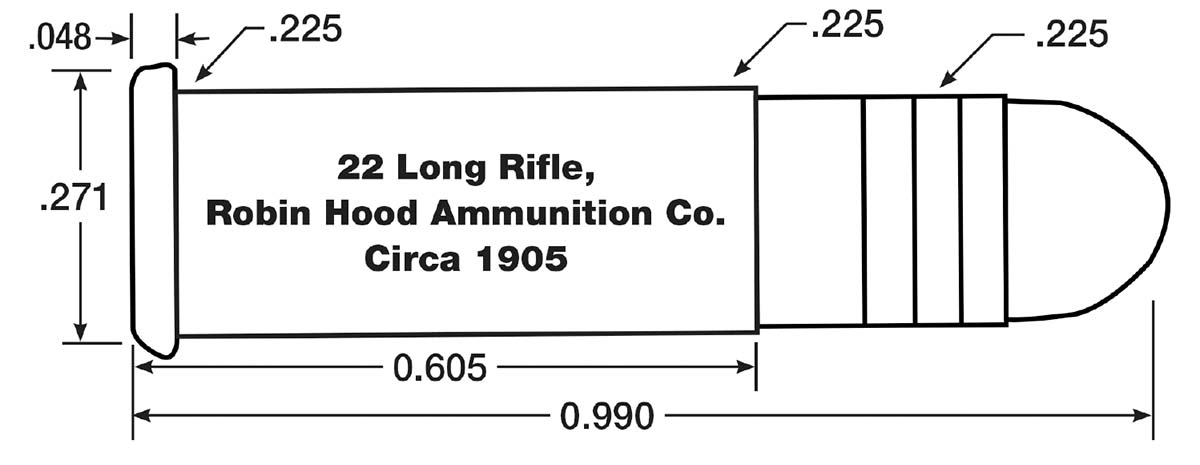

Originally, 22 LR bullets were not crimped in cases, but repeating rifles made crimping mandatory. This newer round shows deformation of the case caused by crimping at the base of the bullet.

Writing in 1886 (before the invention of smokeless powder), he says of the 22 Short, “ I use Winchester cartridges altogether in the 22 and do not clean the little gun until I am through shooting, no matter how many shots may be fired. I shot 160 shots with the 22 without cleaning, and it shot first-rate at the last.” J. Stevens Arms and Tool Co. even said the black-powder 22 Short would shoot “as well as any marksman can hold the rifle” at gallery ranges up until about 1900. This is strange when many hunters of the time said that after two or three shots “squirrel head” accuracy was gone until the bore could be cleaned. Perhaps the time between shots allowed the fouling to harden?

Bullet crimp does not all fold out upon firing, as the photo above shows. Damage to the soft lead bullet base results and can affect accuracy.

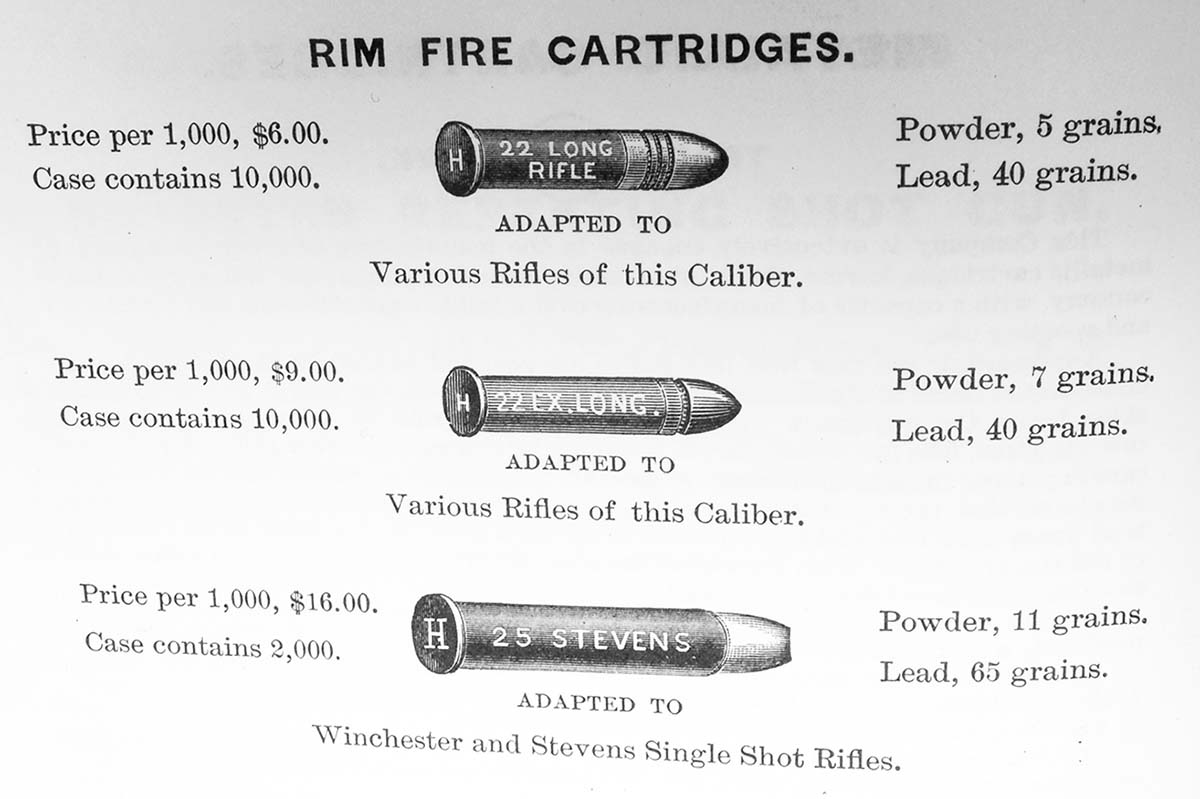

Now comes the biggest mystery on the road to the 22 Long Rifle, the 22 Extra Long (ExL). It came about in the experiments that created the 22 Long. It used a .750-inch case, seven grains of black powder and a 40-grain bullet (perhaps designed by Frank Wesson) seated to the same depth as the 22 Short. The 22 ExL was not produced commercially until about 1878, when target shooters were asking for a rimfire 100- to 200-yard cartridge. Unfortunately, the accuracy of the ExL was not what the paper punchers had hoped for, largely due to improper rifling twist. Also, firing many 22 Shorts or Longs in the ExL chamber left a hard ring of black-powder fouling that impeded or prevented chambering the longer cartridge. Writers of the time blamed all this on the ExL cartridge and continued to do so until it was discontinued in the 1930s. One “expert” suggested anyone owning a rifle chambered for the ExL to simply “throw it away.” The writers just didn’t know what they were talking about, yet they still kept talking. Imagine that, how unique!! Never happens today.

Riflefolk still demanded an inexpensive 22 rimfire cartridge for use on small game and paper targets at ranges of 100 to 200 yards. Common sense would suggest developing the 22 ExL into a highly accurate round and chambering it in correctly made rifles. That, however, was not an option because there was no way to prevent folks from firing mostly the cheaper 22 Shorts and Longs in the guns and ruining the chambers for the ExL cartridge, which thanks to the writers, already had a bad reputation.

Early copper-cased 22 LRs had many headstamps, but mostly the one shown at far right – nothing at all!

The ammunition industry was truly, to use a popular phrase of the time, between a rock and a hard place. Facts were: (1) hard, black-powder fouling was a reality, (2) cleaner burning powders (semi-smokeless and smokeless) did not yet exist, (3) the longer bearing surface of the 45 grain ExL bullet gave better accuracy at longer ranges than the 29-grain 22 Short slug and (4) a rifling twist of 1-in-14 to 1-in-16 inches was necessary to properly stabilize this bullet.

Some rifles and many revolvers like this S&W 22/32 Target had chambers not recessed for case rims, which was dangerous for bystanders if rims ruptured upon firing.

Regarding the development of the 22 Long Rifle, it is recorded that Joshua Stevens in early 1887 asked William Thomas (known in the industry as UMC Thomas) of the Union Metallic Cartridge Co., to produce a 22 rimfire cartridge for 100 to 200 yard shooting in Stevens target rifles. In other words, the same use as the discredited 22 Extra Long! All that could be done, given the previously mentioned facts, was to poke a 45-grain ExL bullet in a 22 Long case with its 5 grains of black powder and call it done. The velocity was probably about 800 feet per second (fps). UMC reportedly delivered the first 22 LR cartridges to Stevens in late 1887. That’s service! But is this really what happened? A UMC price list dated 1884 exists, which shows 22 Long Rifle, 100 in a box. The 22 LR probably came about when the work was being done that created the 22 Long and ExL, but offered nothing as a black-powder round, so it was “put on the shelf.” When Stevens asked for a cartridge, given the bad press of the 22 ExL, the 22 LR was all that was possible.

Many boys’ rifles were still chambered for 22 ExL years after the 22 LR had replaced it in popularity.

The “new” 22 LR cartridges in target rifles by Stevens and Ballard (even with proper rifling twist) did not set the target, better-shooting world aflame, but were considered better than the 22 Long. The 22 LR was really what the 22 ExL should have been.

Few competitors shot groups at the time. Instead, they preferred to sight-in a new rifle, then shoot standing (offhand) for score on a standard paper bullseye target. This didn’t tell much. Vertical stringing of shots at 100 and 200 yards was noted, which usually indicates velocity variations. This was with cartridges in which bullets were not crimped in the case but held by friction alone. The coming of slam-bang feeding pump guns made crimping mandatory and introduced a huge detriment to rimfire accuracy that has not yet been overcome. The demand for a 25-caliber rimfire target cartridge increased! It might have happened, too, but no one wanted to pay the estimated cost of the ammunition!

Next time, we will look at what finally made the 22 LR into an accurate cartridge and the rifles that replaced the hammerfired falling block single-shot on the target range and in the squirrel woods.

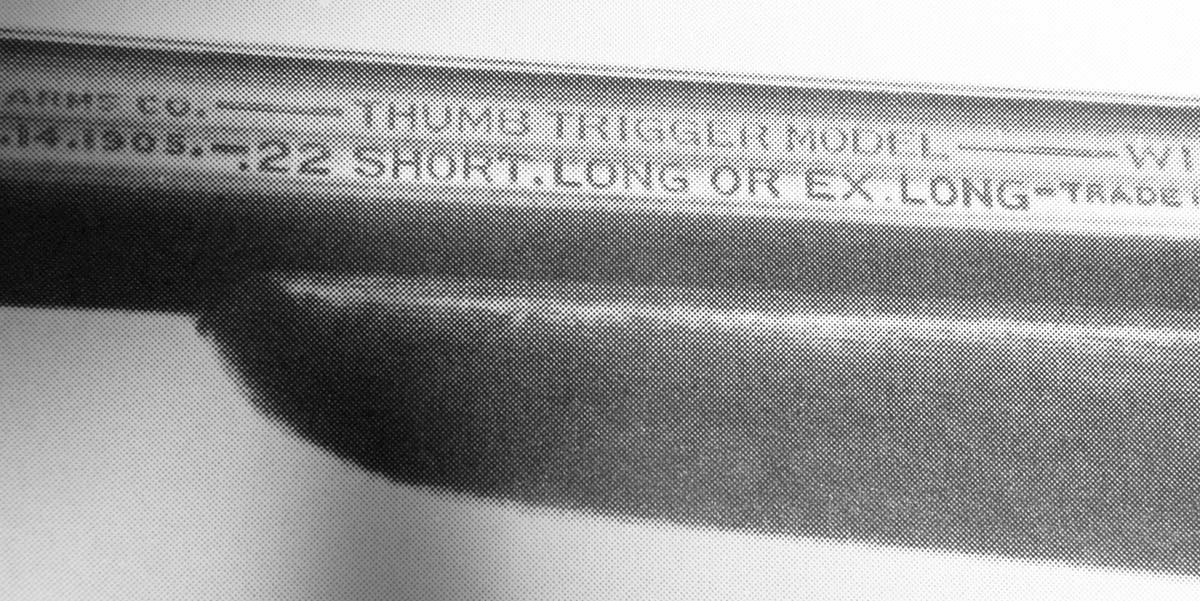

Winchester first offered 22 LR black-powder ammunition in its 1890 catalog.