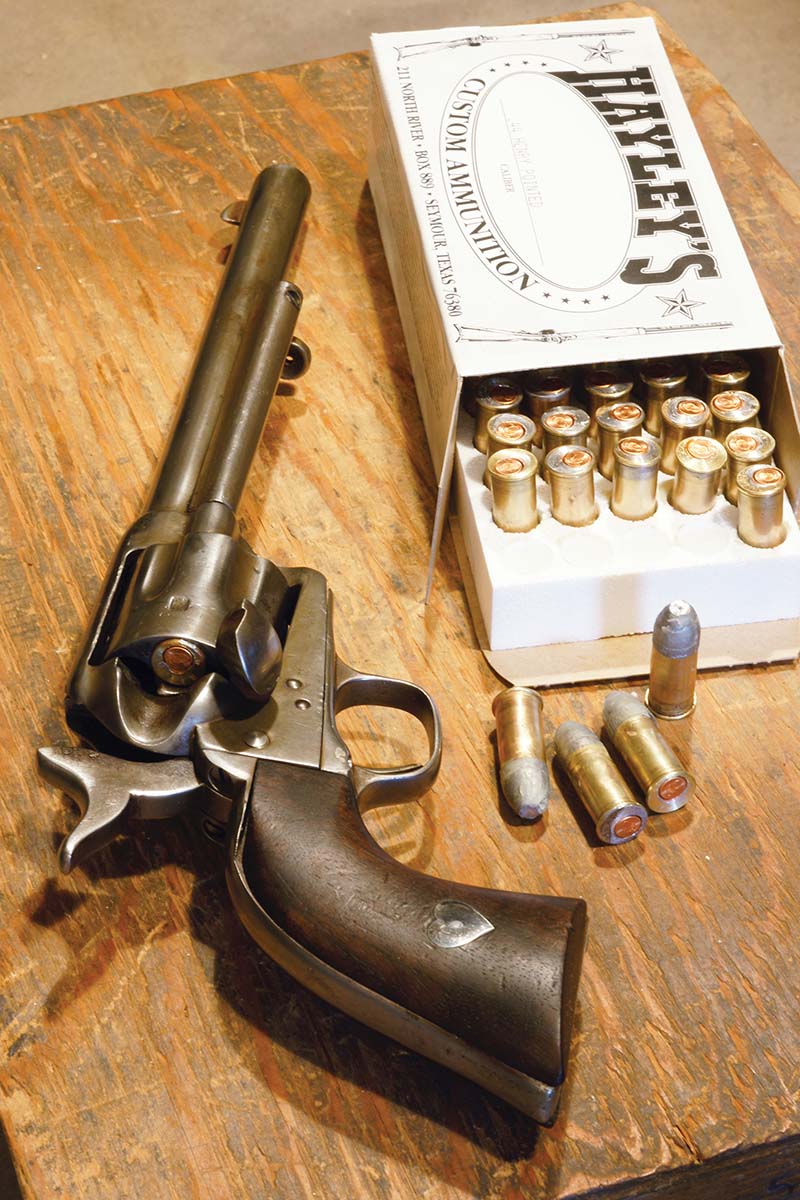

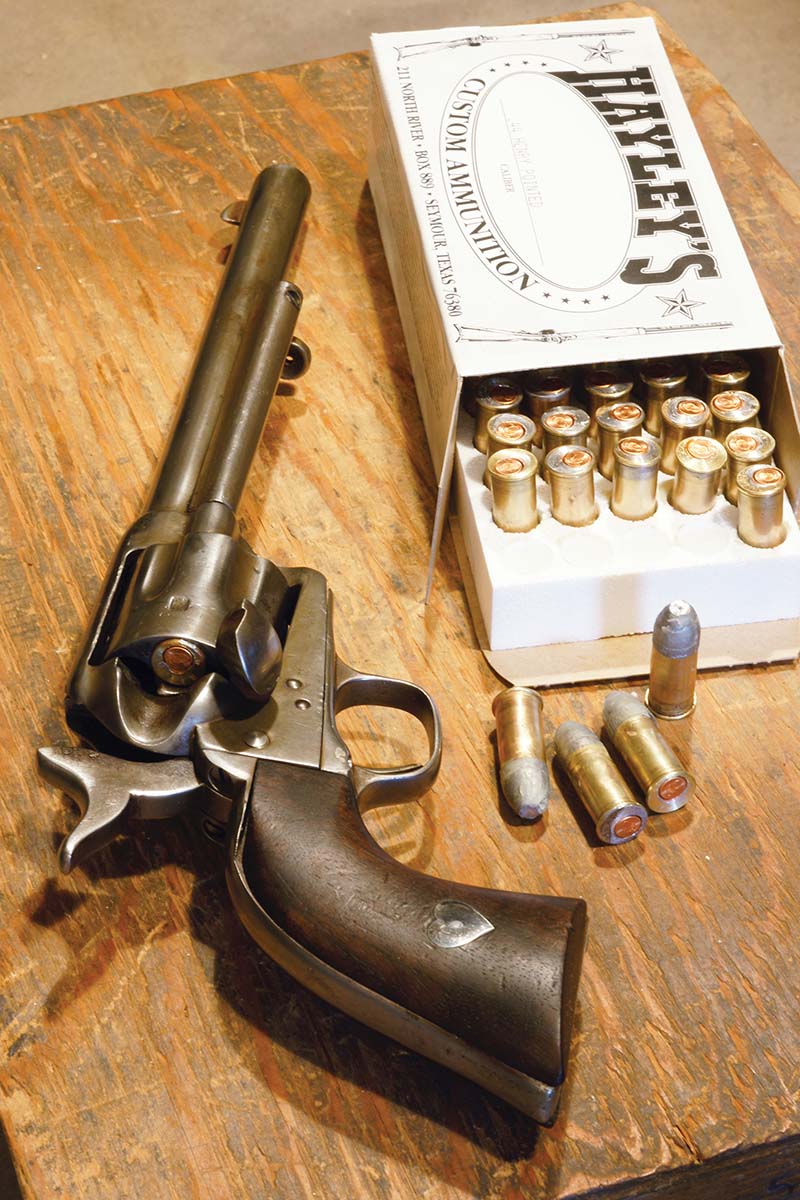

Colt 1860 Army Thuer conversion, with an original gang mould and a supply of its pointed bullets.

It’s now five years since Bob Hayley died, and several more since his debilitating cancer effectively ended production of the “weird, wacky, and wonderful” rifle and handgun cartridges that were his mission in life.

Bob Hayley’s cartridge for the Colt Thuer conversion (left) beside an original. This front-loading design allowed the use of centerfire cartridges without infringing Smith & Wesson’s Rollin White patent, and was the first cartridge to have a self-contained primer.

I should add that Bob was also an ordained Presbyterian minister, so perhaps he had a higher mission, but we never discussed that. On my frequent visits to his small shop on the outskirts of Seymour, Texas, the subject was how I could make ammunition for whatever my latest obscure rifle required. Or, more frequently, what Bob could make for me.

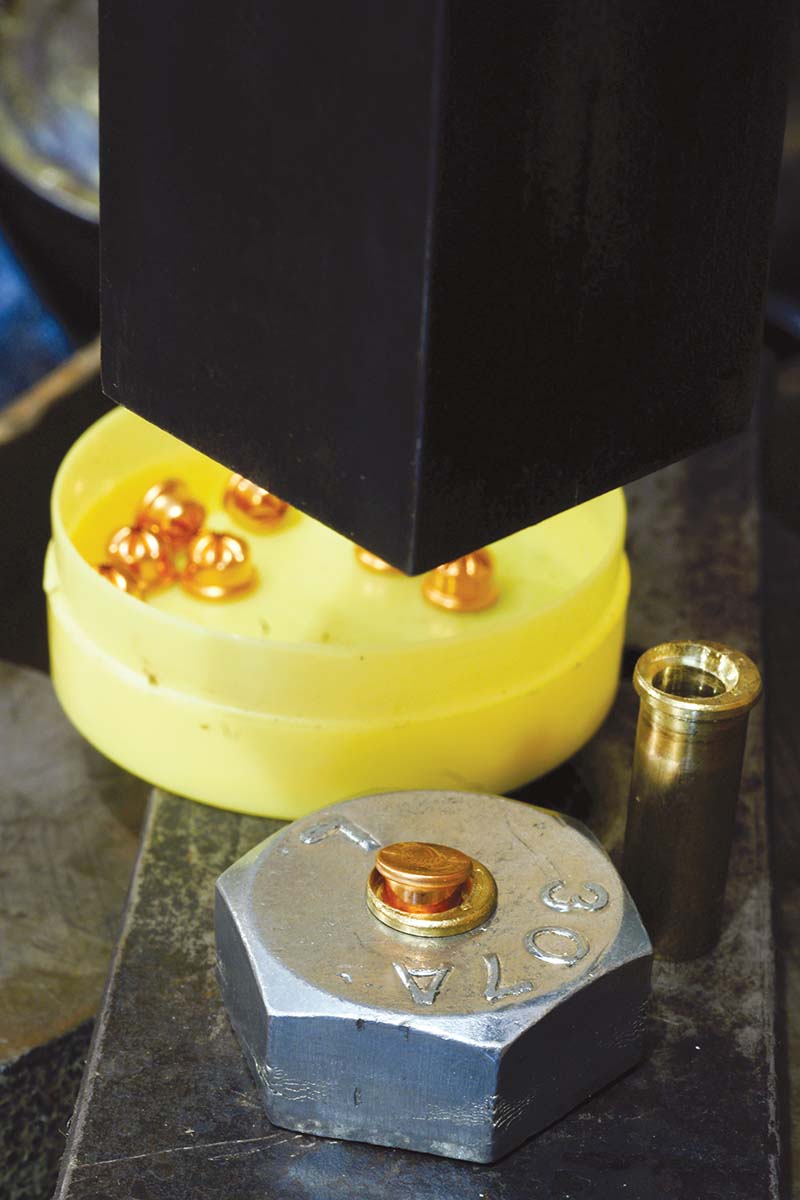

Original Kynoch crimping die for brass 20-gauge cases, with a new cartridge scallop-crimped using a die made by Bob Hayley. With the original die, the crimp is applied using an arbor press, but Bob made his crimping die to fit in a Hollywood Jr. press.

Hayley was one of those iconoclasts one finds in small American towns, living secretive lives that are an enduring mystery to their neighbors. An only child, who never married, Bob got a degree in geology and worked for a few years in the oil industry before moving back to his childhood home in Seymour to look after his aging parents. As he told it, his lifelong passion was guns and ballistics, and following the time-honored route of the self-taught, he managed to turn this passion into a livelihood.

The shop, a short walk from the house through the weeds and rattlesnakes, not only contained two ancient lathes and two drill presses, but a multitude of arcane machines, old and new, for loading ammunition. All of which Bob taught himself to use. He became not only a skilled and ingenious machinist but an expert bullet caster; if he needed a special tool for a particular cartridge, a die to set the crimp in a 20-gauge brass case, for example, he simply made one.

Tools and machining skills are certainly necessary, but equally essential for such an operation is historical information, cartridge dimensions, bullet weights and shapes, ballistic data and over the years, Bob amassed a library of obscure source material to boggle the mind. Among his papers were the complete cartridge dimension charts of the old Kynoch company, which Bob obtained from the Birmingham Proof House when Kynoch discontinued all the old cartridges in the late 1960s.

E.M. Reilly double, originally a 577 Snider double rifle, bored out to 20 gauge. Still a handy little beast. My nickname for it: The Little Thug.

The first essential I learned from Bob was that almost any old gun could be made to shoot once again, provided, of course, that it was sound – all it took was some ingenuity, a few marginal skills and accurate information. It might not have the original firepower or accuracy, but shoot it could. After all, when dealing with a gun made 150 years ago or more, one must adjust one’s expectations.

A Schützen rifle, with loaded ammunition.

The problems in doing this take many forms.

One of the most common is a rifle or revolver made to shoot rimfire ammunition. Today, we have .22 rimfires and not much else, but in days gone by – early in the transition to self-contained cartridges – there were rimfires in calibers up to .44 and even larger. Colt revolvers, Henry repeating rifles, early Smith & Wessons, you name it. Almost all used black powder and were low pressure.

Both the 20-gauge ball and spire-point slugs were cast by Bob Hayley. The spire points are from a mould made for the 1860 Hessian musket.

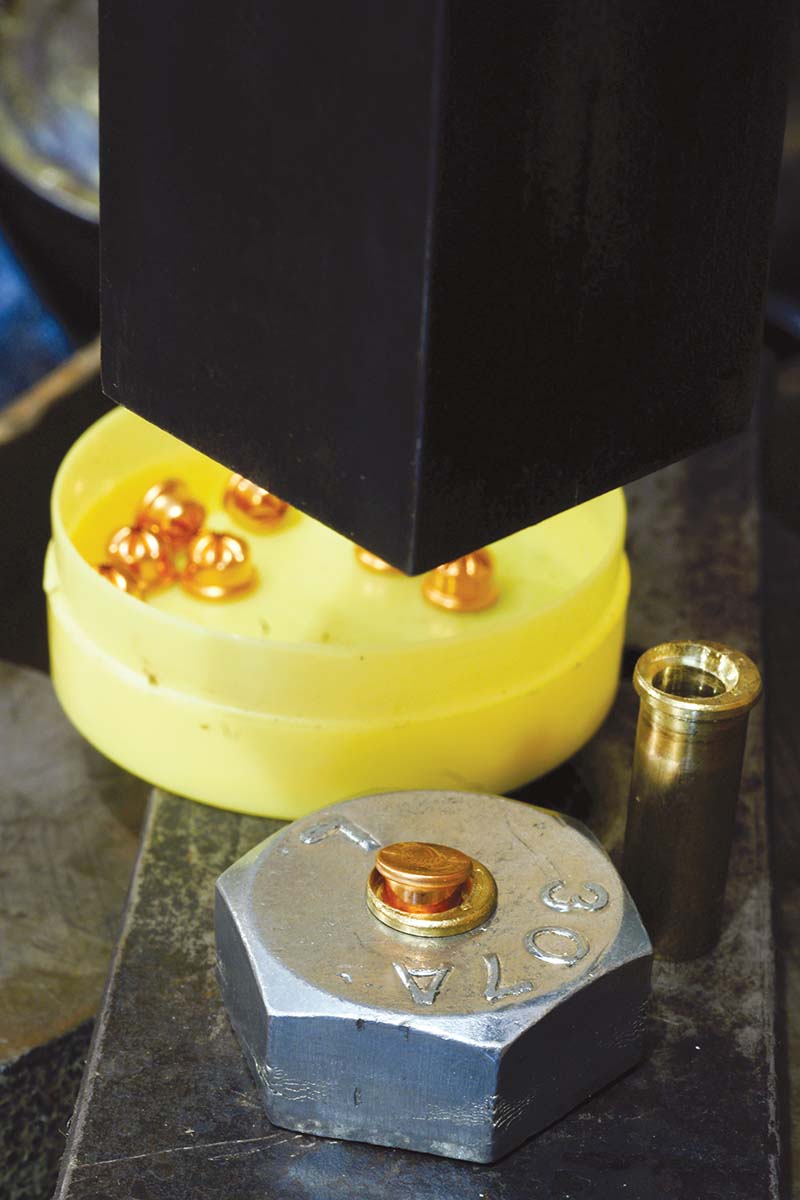

Bob developed a method of making cartridges that were not, strictly speaking, rimfires but could be fired in such a gun. Take the .32 rimfire, one of the most common, as an example: He would drill out the existing primer pocket of a 32 Smith & Wesson Long (or Short, depending on the chamber), creating a larger one set off-center. This was counterbored to allow seating an RWS blank starter’s pistol cartridge.

Cutting the brass to length is easy by using a drill press and a cutting wheel.

Filled with the appropriate powder and one of Bob’s cast bullets, it could be fired by positioning it in the chamber with the RWS cartridge in line with the striker.

In the case of larger calibers, Bob first filled the existing primer pocket and flash hole by soldering in a piece of copper wire, filing it level to give him a solid head, then drilling a new pocket off-center to accommodate the RWS round.

Bob’s rotary swage was an important piece of machinery for refashioning old brass from new.

These cartridge cases were reloadable virtually forever, so the high initial price for a box of 50, usually about $250, was amortized pretty quickly if you did much shooting in, say, Cowboy Action.

Making brass for some of the more obscure, obsolete cartridges could get more complex. For example, ammunition for the Colt Thuer conversion from the 1860s. This converted the 1860 Army percussion revolver to centerfire without infringing Smith & Wesson’s Rollin White patent. It required cartridges with no rims and tapered from front to back, rather than back to front, for loading the cylinder from the front. Bob did it by swaging down 45 Auto cases, trimming the resulting rim, then forcing the case, inverted, into a 303 British die. All that remained was to trim the mouth, seat the primer and load.

By comparison, something like the 25-20 Single Shot was simplicity itself.

Stages of fashioning my 11.15x51R Kurz cartridge, beginning with 43 Mauser brass, cut down to 2.1 inches, and then to 2.0 inches. The bullet is a 370-grain hollow-base from a custom mould, cut to duplicate the original UMC bullet for the .43 Mauser and .43 Spanish. Note the convex base of the cartridge case, known in Germany as the Type-A.

In 2018, I showed up in Seymour with a Stevens Model 47

Schützen rifle I bought on a whim at Rock Island. It was chambered for the 25-20 Single Shot, forerunner to the 25-20 Winchester (25 WCF). It became, to all intents and purposes, obsolete the minute Winchester chambered the Model 92 in 25-20, and brass became scarce. Then, because the 25-20 SS was the base case for the wildcat R2, Lovell, Griffin & Howe commissioned a large run of brass in the late 1930s, and this supplied the market for years. Bertram later listed 25-20 SS brass, but before that became available, Bob Hayley developed his own.

Cases for the 25-20 Single Shot (left to right): an original case, Hayley’s manufactured case and the 223 Remington from which it is made.

Using 223 Remington brass as his starting point, he reduced it to size in his rotary swage, trimmed appropriately, ran it into a sizing die and finally fireformed. The swaging process moved a lot of brass around, which affected case capacity significantly. A competent and prudent handloader could compare the differences and load accordingly.

Making 32 rimfire requires drilling out the existing primer pocket and flash hole in 32 S&W Long first, then drilling and counter-boring a new pocket to accept an RWS starter’s pistol blank.

This essentially describes Bob’s process for many different obsolete cartridges. His usual cartridges as raw material included the 223, 303 British, 348 Winchester and 300 Remington Ultra Mag. He used the 300 RUM to make 280 Ross brass for me when I acquired a Ross Model 10, and it worked very well indeed.

You will notice that several of the old calibers mentioned here are once again available, in theory if not always in practice, from Bertram in Australia, Quality Cartridge or Starline. But years ago, such was not the case. Having used brass from all of these sources, for several rifles, I can attest that Hayley’s home-made stuff worked perfectly well, even if it was more expensive and less convenient. The important point is that it kept old guns shooting when there was nothing else, and Hayley’s success undoubtedly influenced manufacturers to produce obsolete brass.

Wieland firing the E.M. Reilly. It was originally a 577 Snider double rifle; bored out to 20-gauge, it is still an admirable weapon for short-range defense.

At various times, Bob also made both cases and loaded ammunition for retail suppliers such as Huntington Die Specialties and the Old Western Scrounger. In fact, it was Fred Huntington (son of the founder of RCBS) who introduced me to Bob way back when. Bob also supplied some of the raw material for others in the game who purported to do what he did. When he died and the supply dried up, they were out of business as much as he was.

A Colt revolver and 44 Rimfire.

One gun I took to him was fascinating in itself, but provided less of a challenge. It’s an E.M. Reilly that began life in the 1870s as a 577 Snider double rifle. Its barrels were later bored out to become a 20-gauge shotgun, but I wanted to employ it as a sort of Cape gun, able to fire both shot and ball.

Bob had some old 20-gauge paper cases we packed with black powder and shot. For ball, we got some Brazilian Magtech 20-gauge brass cases, and Bob cast both round ball and spire-point slugs. To hold the slugs in place, Bob machined a die to impart a scallop crimp to the brass case. Not having a loading press big enough to handle it, Bob sold me an old Hollywood Jr. press (circa 1960) he had tucked away in one of his outbuildings. (Beware of snakes.)

This Winchester Low Wall was chambered for 32 Rimfire, but the chamber had eroded sufficiently to allow use of Bob Hayley’s rimfire ammunition made from 32 S&W Long.

This whole operation was child’s play to Bob Hayley. More challenging was a German

Schützen rifle from the 1880s, chambered for one of the seemingly infinite number of obscure proprietary cartridges of the era. First, we slugged the bore and made a chamber cast, and given the era, Bob deduced it was probably based on the old 43 Mauser case or something similar.

RWS blanks are seated using an arbor press, but this can also be done with a vise.

Bertram makes 43 Mauser brass, which was formerly marketed by Huntington, and Buffalo Arms offers brass from Starline. Since chamber length was indeterminate, it had something like a forcing cone instead of a distinct ledge. I cut the brass down a bit at a time until I reached a length that did not stick. Bullets were no problem, since Bob had a custom mould to make 370-grain hollow-base bullets for the 43 Mauser

et al. A modest load provided three fire-formed cases which I sent off to Redding, and a month later, I received a set of loading dies I christened 11.15x51R

Kurz.

Removing a few thousandths to bring rim diameter down to size, using a belt sander. Tread carefully, allow the sander to spin the case, and you’ll end up with a perfectly round, perfectly sized rim.

Making ammunition is relatively easy. Cases are cut to length, trimmed and squared, run into the sizing die and then fireformed. From there, they are, seemingly, infinitely reusable given the low pressures to which they are subjected. I have never found a load, working with black powder, smokeless, and a couple of duplex combinations, that would consistently deliver the accuracy the old girl was capable of back in 1880, when she first saw the light of day, but that’s the nature of the game, dealing with “old iron,” as the Germans termed it.

A couple of years after Bob’s death, I was confronted with a similar situation, this time involving a gorgeous Austrian hunting carbine, built on the Werndl single-shot handgun action by Ferdinand Frülich of Vienna. Frülich was a noted maker of fine firearms, and a supplier to the court of the Emperor Franz Josef. Again, the cartridge was unknown.

This time, alas, I could not dial the familiar Seymour number and hear Bob’s clipped “This is Bob Hayley…” I was on my own.

Various stages in production of the 11.2 Werndl (or 11.3 Montenegrin): (1) It can be made from either 45-70 or 40-65 brass. The (2) red-tinted one was made by Lee Shaver from a 45-70 case, patterned on the chamber cast. (3) the 40-65 brass, then (4) a case cut down and trimmed and finally, (5) a loaded round.

Since I was taking the rifle to Lee Shaver for a complete strip and assessment of condition, I asked him to slug the bore and do a chamber cast while he was at it. The result was a cartridge with base dimensions remarkably close to the 45-70 and, as I later discovered, even closer to the 40-65. By some freak of fortune, I had a good supply of Starline’s excellent 40-65 brass, so I was all set.

All that’s required is to trim to length, reduce the rim by a few thousandths on a belt sander, bell the mouth, stuff it with suitable black powder and seat a bullet. For that, I obtained some soft lead .430-diameter, 200-grain bullets. Soft lead allows the bullet to bump up from .430 to almost the .440-groove diameter, resulting in a tight enough fit to give adequate accuracy.

Redding case trimmer with a variety of pilots allows exact trimming to length with a perfectly square case mouth.

I found out later that what I had was, officially, an “

11.2x36 Osterr.-Ung. Kavallerie-Revolver M. 1870.” The Austro-Hungarian army briefly adopted a Werndl handgun in this chambering, and when it abandoned the gun to move to a Gasser revolver, it retained the cartridge. This later became a common chambering in the bizarre oversized revolvers the king of Montenegro decreed all adult males must carry, and one of its many aliases – it has more than two dozen – is the 11.3 Montenegrin. At one point, this was made by almost every European ammunition company and even, briefly, in America by Winchester. Standard dimensions, however, were elusive.

Anyway, it has my lovely Frülich-Werndl shooting, and holding its own in the local black-powder matches.

Over the course of my 12-year association with Bob Hayley, I learned a lot about rifles and cartridges, and all the arcane processes that go into making them work. The most important lesson, though, was that almost anything can be made to shoot again. All it takes is some determination, ingenuity and a few basic machining skills. See? Simple.

Frülich-Werndl stutzen rifle, with loaded rounds. A lovely little black-powder carbine for short-range shooting.