.40-65 Winchester Center Fire

Loads for a Shiloh 1874 Sharps

feature By: John Barsness | April, 20

Shiloh named this particular model the “Montana Roughrider,” and it appeared in the classified section on an internet site. The ad claimed it was in “like new” condition, with photos backing that up, and included with the rifle was a set of reloading dies and 80 rounds of Ventura Munitions smokeless factory ammunition loaded in Starline’s excellent .40-65 headstamped cases. The price for everything was considerably less than ordering the same rifle, so it did not take long to succumb.

In several ways, the .40-65’s present existence is a minor miracle. Essentially the .45-70 tapered (not necked) down to .40 caliber, it appeared in 1887 primarily as a lighter-recoiling hunting cartridge for the 1886 lever action. Winchester also made a few 1885 single shots for the round, and Marlin eventually chambered the .40-65 in its Model 93 lever action.

The factory load featured a 260-grain bullet, and while some references claim this relatively light bullet flattened trajectory, muzzle velocity was only 1,325 to 1,420 fps (the exact number varies in different sources). This is not all that fast even for black powder, since some British black-powder “Express” rounds from the same era achieved 1,800-plus fps, as did the original black-powder service load for the .303 British introduced in 1888. (France introduced the first smokeless rifle and cartridge in 1886, so the Brits knew smokeless was the future, but their notorious Cordite “powder” was not quite ready for prime-time. The “fast” black-powder .303 round was a transitional solution.)

Believe it or not, the .40-65’s twenty-first-century popularity resembles the 6.5 Creedmoor’s reason for being, though in a much smaller niche market. The Creedmoor became popular partly because it offered higher ballistic coefficient bullets compared to larger caliber cartridges. This resulted not only in lighter recoil with more downrange energy, but less wind drift, making precise hits easier at longer ranges.

This is also exactly what the .40-65 offers the subset of rifle loonies who shoot black-powder cartridge rifles. The most popular .40-65 target handloads use pointy cast bullets weighing around 400 grains, far heavier than the original 260-grain factory load – but also far lighter than any .45-caliber bullets with the same ballistic coefficient. This results in noticeably less recoil than various .45-caliber BPCR cartridges, which is important when shooting extended matches.

Some hunters also use the .40-65, though they often load somewhat lighter bullets at higher muzzle velocities to flatten initial trajectory, since very few BPCR hunters shoot big game at ranges typical of “long-range hunters” using smokeless cartridges.

This increase in bullet weight necessitated faster rifling twists than the original .40-65 twists, which were as slow as 1:28. The most common today is 1:16, the twist I measured in my Rough-rider’s 30-inch octagonal barrel using the standard cleaning- rod method with a cotton patch around a tight bore brush. Afterward, I also slugged the bore to determine groove diameter, which proved to be .408 inch, typical of today’s .40-65s, slightly larger than the original .406. (One of my “specialist-rifle” friends, BPCR fan Mike Korn, owns a nineteenth- century Remington Rolling Block with a barrel some previous owner had relined to .40-65, also with a 1:16 twist and .408 grooves.)

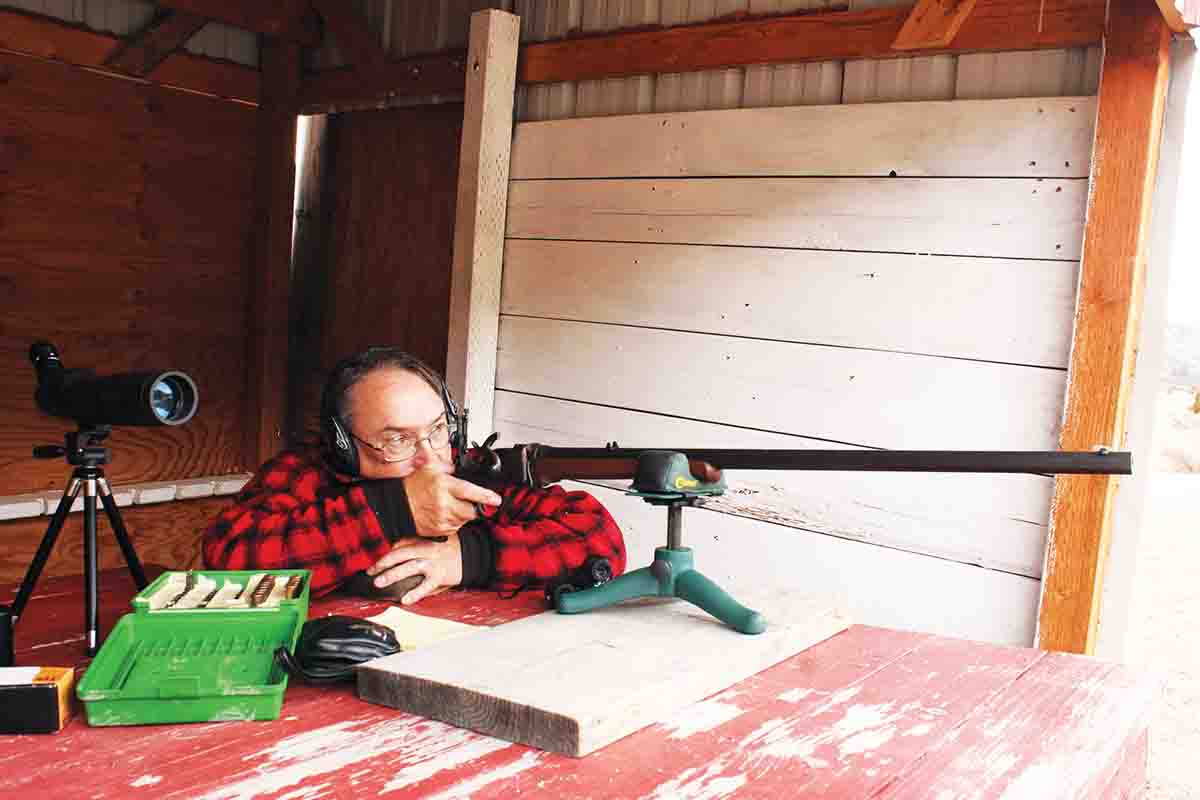

The first range session took place with Ventura factory loads, partly to sight-in the semi-buckhorn rear sight and partly to obtain empty cases for handloading. The bullets were covered in a hard, slate-colored lube, probably powder-coating. While the boxes were marked 255 grains, I broke one round down to check the smokeless charge then, due to a moderate case of obsessive-compulsive disorder, also weighed the bullet, which balanced a Redding mechanical scale at 265 grains.

The charge was 24.0 grains of a small-grained extruded powder, and muzzle velocity averaged a little over 1,400 fps, approximating the original factory load. The 10-pound rifle proved very easy to shoot, both because of very light recoil (calculated at 5.8 foot-pounds using Sierra’s Infinity program) and because the pull of the set trigger averaged a very crisp 15 ounces.

The empty cases were then loaded with the only approximately appropriate bullets on hand, .406-inch diameter roundnose, copper-jacketed 300-grain Hawks. Hawk makes many bullets appropriate for older, often obsolete cartridges, and back in the day, both the .40-65 and several other .40-caliber black-powder rounds used .406-inch bullets.

While it might seem weird to try undersized jacketed bullets, over the past couple decades I have often found them to shoot very well, because some lead-core bullets can actually “bump up” in diameter when booted with relatively fast-burning smokeless powders. Perhaps the two most useful instances involved .224 varmint bullets in the .22 Savage High Power, where the standard groove diameter is .227 inch, and .308 diameter bullets in more than one .303 British.

After those tests, I ordered several more items, first and most important the Black-powder Cartridge Reloading Primer, 9th Edition (2017) by noted BPCR shooters Steve Garbe and Mike Venturino (wolfeoutdoorsport .com). My much earlier edition had wandered off somewhere, and while I have handloaded for a number of black-powder rifles, they have been spaced far enough apart for me to occasionally forget pertinent loading details. The latest edition proved to be even better, partly because it included more info on the .40-65.

I also bought a couple pounds of Olde Eynsford FFg, a new black-powder made by Goex and sold by Hodgdon. It has already gained a reputation for being very clean-burning (for black powder), with extremely consistent velocities. Some Swiss and Schuezten FFg were already on hand, since both brands are favored by many BCPR shooters.

I also placed an order with Montana Bullet Works. Its custom hand-cast bullets are not only very good, but you can specify different sizing diameters. I ordered three different bullets sized to .409-inch (the traditional .001-inch over groove diameter) with SPG black-powder lube.

One other advantage of Montana Bullet Works (MBW) is that it lists the specific mould for each bullet. You can test several before ordering a mould of your own to see what your particular rifle might prefer. You can also simply order more bullets from MBW, which is what I often do these days. The three bullets were the SAECO 410-grain 740, RCBS 350-grain 82702 and RCBS 300-grain 82070, as listed by MBW.

Yet another addition was one of Pedersoli’s Mid-Range Creedmoor tang sights for more precise aiming. Of course, more knowledgeable readers will know that the “Creedmoor” comes not from modern cartridges of that name, but a famous shooting range on Long Island, New York, where in the late 1800s teams of target shooters from different nations often competed against

Aside from the black-powder loads suggested by Garbe and Venturino and the smokeless data from Lyman, quite a bit of new .40-65 data has recently shown up in other places. Hodgdon, for instance, lists eight smokeless powders from H-4227 to Varget for 400-grain cast bullets, along with one load using Trail Boss. However, even the starting smokeless charges are listed as getting close to the maximum 1,500 fps suggested by MBW for the lead alloy used in its bullets – and the Hodgdon test barrel is only 24 inches long, rather than the 30 inches on my rifle. As a result, I confined my testing to Trail Boss.

I also checked the Western Powders website for information on Blackhorn 209, the company’s excellent powder for in-line muzzleloaders. Blackhorn also works very well in BPCR shooting, providing a satisfying puff of smoke with bore fouling that superficially resembles black-powder fouling but is relatively thin and soft. It is also NOT hygroscopic so it will not corrode bores or brass. I had previously used Blackhorn to handload black-powder equivalent ammunition in cartridges from the .32-20 to .50-70 with excellent results, and they added a load for the .40-70 with a 410-grain cast bullet!

Since the resurgence of BPCR shooting, plenty of testing has proven that large rifle magnum primers work best with black powder, resulting in less fouling and more consistent velocities. The traditional solution has been Federal 215s, which when introduced were the hottest American large rifle primer.

Unfortunately, during the “Great Obama Shortages,” F215s turned into “unobtainium.” Eventually I switched to CCI 250s, partly because they were actually available, but partly because Allan Jones of CCI/Speer informed me the priming compound in CCI magnum primers had been upgraded to a hotter mixture in the early 1990s, so they are at least as hot as 215s. The 250s worked great in all my handloading of larger smokeless and black-powder rounds, so I used them again in the .40-65.

CCI 200s were used for all the smokeless and Blackhorn loads. In fact, Western’s Blackhorn cast-bullet load was the first handload fired after the Ventura and Hawk smokeless loads. The listed 31-grain charge filled the case to almost the same level as the 50-grain charge chosen for testing the 410 SAECO bullet with the three FFg black powders.

Western advises using an over-powder wad with Blackhorn, so I topped the charges with the same wads used in the black-powder loads, cut from a cardboard milk carton using a .40 S&W case with the mouth chamfered to a sharp edge, which worked perfectly. (This may seem to be a “cheapo method,” but Steve Garbe uses milk carton over-powder wads, and that’s good enough for me.)

This was also the first trial with the tang sight, and three shots with the Blackhorn grouped into a little over an inch at 50 yards. A little later the load also proved to have almost exactly the same point of impact (POI) as the best 410-grain black-powder load. (While Blackhorn 209 is more expensive per pound than black powder, a considerably lighter charge produces the same approximate results as black, so the cost per shot is very similar.)

Most test-firing was done at 50 yards because previous experience with black-powder rifles indicated POI could vary considerably when using everything from light loads of A-5744 to cases full of black powder. Shooting at 50 yards kept all the test groups on paper, but I also shot a few groups at 100 yards with some of the loads, including the Hawk with A-5744. Per usual, they averaged twice as large as at 50.

The preliminary work with the three brands of black powder used the 350- and 410-grain bullets. This rifle “liked” Olde Eynsford by a relatively small but definite margin with the 410s, and a much wider margin with the 350s. One nifty feature is that three shots from each of the three listed Olde Eynsford loads ended up in a nine-shot group spanning slightly less than 2 inches at 50 yards, so they can be used interchangeably without adjusting the sights.

Even with the 410-grain loads the recoil proved to be relatively mild compared to heavier bullets in .45- and .50-caliber black- powder rounds. Sierra’s program computes around 11 foot-pounds, about like a typical .243 Winchester deer load in an 8-pound bolt rifle – and almost exactly half as much as my 1866 Springfield

.50-70 generates with 525-grain loads. The last range session took place in early December on a cloudy day, ending up not long before sunset – when I could easily watch sparks and flames jetting from the muzzle while touching off the set trigger. The revival of the .40-65 WCF is not only practical, but fun!

.jpg)