A Breed Apart

The .500 Jeffery and .505 Gibbs Rule Their Class

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 21

There was not a trace of blue left, but nor was there a trace of rust. It fit Ernest Hemingway’s description from The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber – “this damned cannon” – perfectly. The .505 Gibbs is one of that select class of cartridges that are big, highly specialized and – in former days at least – were what Hemingway called “the graceless tool of the professional.”

Let’s start with weight. A really big rifle is heavy, partly because the barrel and action are larger, but also to reduce felt recoil and be stout enough to withstand the repeated pounding.

Carrying a 12- to 16-pound rifle all day, every day, is beyond most of us – at least if we want to be able to handle it quickly in an emergency. In the old days, a hunter would have a gun bearer to carry it, while arming himself with something lighter and handier, like a .450 or .450/.400. This is not a matter of laziness: There are exceptions, as with everything, but carrying a 14- or 16-pound rifle all day takes it out of you.

Then there is recoil. Even in a 12-pound rifle, the recoil of a full-powered .505 Gibbs or .500 Jeffery is severe. In the usual 10.5-pound rifles made today, it’s much worse, and the .500 Jeffery, as originally conceived, was frightening.

At this point, some readers are sure to be leaping to their keyboards to insist that recoil can be tamed with muzzle brakes and other devices. A few years ago, one custom rifle maker produced cannons like these with 18-inch barrels and muzzle brakes – a concept that gives me the vapors. Aside from damage to your hearing, such short barrels result in a serious loss of velocity, and if you are losing substantial power, what’s the point?

These are rifles intended for the shortest ranges – from right at the muzzle with a charging beast, out to, say, 50 or 60 yards. Open sights are not only all you need, anything else can be detrimental or even physically dangerous. Getting your forehead smacked by a scope on a .300 Weatherby Magnum is bad enough; on a .500 Jeffery, it could mean serious injury or, if it happens in the middle of a buffalo charge, death for you, if not him.

At this point, I’ll agree that, yes, there are exceptions to everything. What I’m setting down here is not based on just my own experience but also on conversations with professional hunters going back 50 years. No technological advance during that period has changed the essential points regarding dangerous-game rifles, and the .500 Jeffery and .505 Gibbs are, in bolt-action terms, at the top of that list.

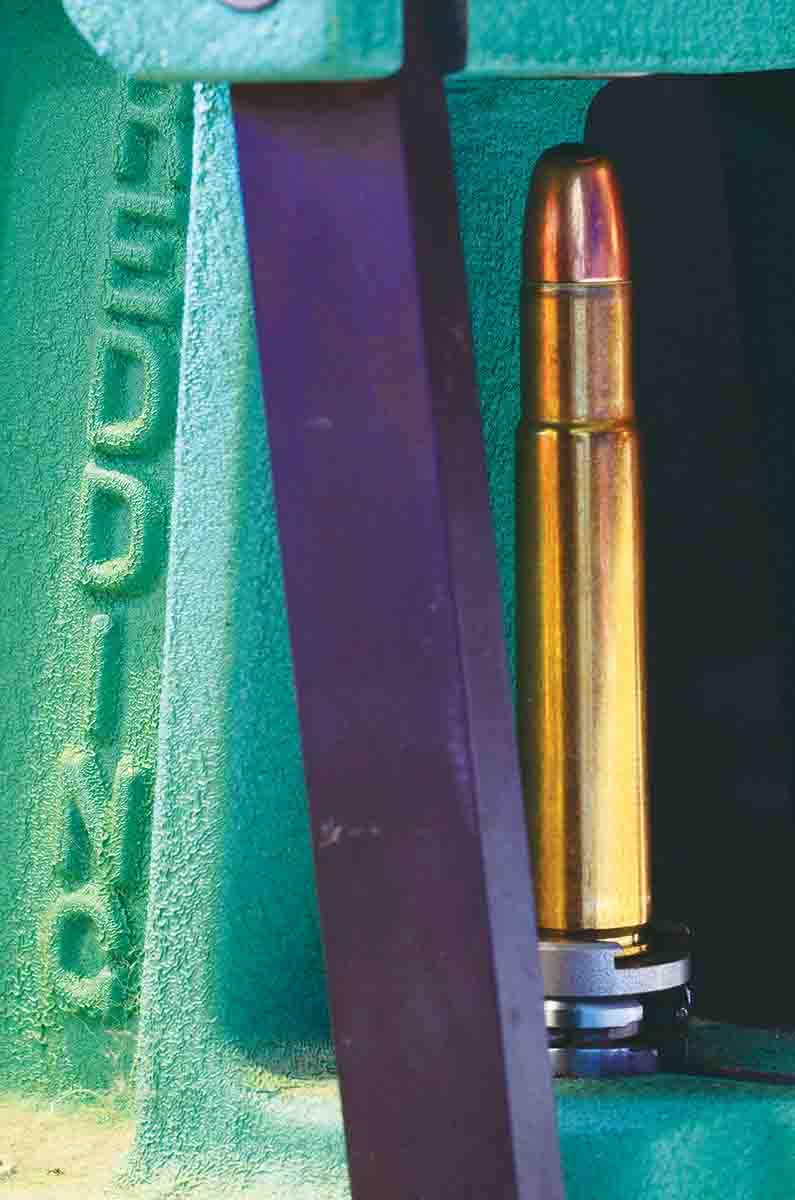

Although both cartridges are rimless .500s intended for bolt rifles, their histories could hardly be much different. The .505 came first, introduced in 1913 by George Gibbs. It was originally known as the .505 Magnum, among other designations, and was intended to replicate the performance of the .500 Nitro Express in the then-new magnum Mauser bolt action. Think of it as a scaled-up .416 Rigby, and you won’t be far wrong. It fired a 525-grain bullet ahead of 92 grains of Cordite, for a velocity of 2,300 feet per second (fps.)

The .500 Jeffery is completely different. According to George Hoyem, who researched these matters more extensively than anyone else, it was created by Richard Schüler (August Schüler in Suhl) in 1923. He chose to call it a .500 rather than the metric 12.7mm; it fired a 535-grain bullet, ahead of 95 grains of R-5 Swedish flake powder for a velocity of 2,400 fps. Four years later, W.J. Jeffery of London adopted the round, called it the .500 Jeffery and began making rifles.

The .500 Jeffery is shaped like a fireplug, with a very short neck (.300 inch versus the Gibbs’s .620 inch) and a rebated rim. It was never intended to fit the magnum Mauser action; instead, Schüler wanted a cartridge he could shoehorn into the standard military Mauser 98, which was cheap and readily available after 1918. Keep in mind, this was at the time of the German post-war hyperinflation. He designed an in-line, two-round magazine and had himself a cheap, dangerous-game rifle for sale to farmers in Africa. In a rifle weighing only 8 pounds, the recoil from this beast does not bear thinking of. I once handled one, but did not have the opportunity to shoot it. Oh, shucks.

The rim was rebated to allow it to fit the standard Mauser bolt face. A rebated rim can cause problems with the bolt riding over it and jamming. In the Schüler in-line magazine, there was no such problem, but it can present difficulties in a standard, staggered, box magazine where there is less rim to grip. Overall, the cartridge was an attempt to get the most out of the least, at the lowest price, and no one can deny it does that.

Unlike the .505, which requires a bullet of .505-inch diameter, the .500 Jeffery uses the standard .510 diameter of the .500 Nitro Express. Although physically smaller, with less powder capacity, on paper, the .500 Jeffery is slightly more powerful than the .505 Gibbs and was known, until the advent of the .460 Weatherby Magnum in 1958, as the most powerful magazine-rifle cartridge in the world. This aura has stuck with it into recent times.

Around 2005, CZ began offering its magnum rifle in both .500 Jeffery and .505 Gibbs. If the action is the same size and the price is the same, there is no advantage whatsoever to the .500. In fact, between its shorter length – allowing cartridges to slam back and forth in the magazine under recoil – and the rebated rim, there are actual disadvantages. Still, when Norma introduced its African PH line of ammunition around the same time, it included both cartridges; five years later, I was told sales of .500 Jeffery outpaced .505 Gibbs by six to one.

As hunters might imagine, loading data for both is hard to come by. In 1996, I was involved in producing the A-Square loading manual, the first to really develop loads for these cartridges, complete with piezoelectric pressure testing. I created loading tables for both, using A-Square bullets, which are no longer available. Still, the data is the best I have. Today, bullets are available from Woodleigh, Hornady and Swift, among others, in both softs and solids, but the companies do not always provide load data.

For this article, I worked mostly from the data in the A-Square manual, staying at accepted pressure limits and chronographing each load. I used both Hornady DGS solids and Swift A-Frames, in 525 and 535 grains (.505) and in 535 or 570 grains in the .500.

Published data is usually derived from 24- or 26-inch barrels, whereas my rifles have barrels of 22.5 inches (Blaser R8 .500) and 21.5 inches (Granite Mountain .505). This resulted in substantial velocity reduction. For comparison, I also tested some Norma factory ammunition to compare velocities and velocity loss.

The Blaser R8 came from the factory with a similar setup, although I don’t know the exact distances or ammunition it’s intended for. Its rear sight is not readily adjusted – which is good in such a hunting rifle – but makes it tricky when developing loads.

Sights on these rifles need to be extremely durable, preferably with nothing easily movable (such as a folding leaf) because recoil will make mincemeat of adjustable sights. If I could have the standing blade welded in place, I would.

Such sights do not lend themselves to shooting five-shot groups at 100 yards even if it made any sense, which it doesn’t, or if my long-damaged (and increasingly arthritic) shoulder allowed it, which it won’t. My goal with all loads in the .505 Gibbs, given its sighting arrangement, is sufficient velocity with a good bullet placed as close to dead on at 20 yards as possible, with no problems resulting from excessive pressures, such as sticky bolts.

In the .505, Reloder 22 proved to be the best powder for the purpose with Hornady bullets. Still, with the short, 21.5-inch barrel, it delivered about 250 fps lower velocity than was achieved in the 26-inch A-Square pressure barrel. In the Blaser, H-4895 proved the best with both 535- and 570-grain bullets.

A word about barrel length: With a long magnum action, putting a 26-inch barrel on a .505 Gibbs makes it quite unwieldy – not what you want hunting elephants, or anything else, in thick bush. The same applies to the Blaser R8, although its shorter action allows an extra inch of barrel length without changing the equation. The Granite Mountain was slightly heavier at 10 pounds, 8 ounces, than the Blaser (10 pounds, 5 ounces). Naturally, this reduces the sight radius with a commensurate reduction in precision, but these are short-range battle axes, not long-range rifles.

To make them anything approaching handy, the barrel must be relatively short, but reducing barrel length from 26 to 22 inches reduces velocity noticeably. In these rifles, I think it’s a mistake to try to push the limits to get the velocity back to what the ballistics tables tell you is possible. In a specialized, last-resort, dangerous-game rifle, reliability trumps every other consideration, including bullet velocity, foot-pounds at the muzzle and pinpoint accuracy.

Pushing pressures to the max can cause case sticking and stiff bolts, among other things; as well, large gulps of slow-burning powders can be hard to ignite, and the slower they are, the harder it is. Many would-be developers of huge cartridges find they cannot get reliable ignition even with magnum rifle primers, and this is something to keep in mind – one more way in which big guns like these are not like all the others and must be treated differently.

Asked to choose between the .505 Gibbs and .500 Jeffery, my answer would be that there is no doubt in my mind that the .505, with its larger case capacity, could be made to out-perform the .500. This would involve pushing pressures beyond The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) and Commission Internationale Permanente (CPI) limits, which I’m not about to do here. Worse, at a practical level, a handloader could encounter the various difficulties with reliability that go with pushing pressures.

In the final analysis, the .505 Gibbs was designed as the ultimate dangerous-game cartridge for a bolt action, by a gunmaker who knew about dangerous game, keeping pressures low and reliability high. The .500 Jeffery, on the other hand, was designed to give comparable performance but by cutting every corner, stretching every limit and hoping for the best. If my life were on the line, I’d take the Gibbs every time.

.jpg)

.jpg)