Cartridge Board

3-Inch 20 Gauge Part I

column By: Gil Sengel | April, 17

At any rate, our interest here is not muzzleloading guns, except to say that the rule for describing the size of the hole in large smoothbore barrels far predates the cartridge era. It goes back before the percussion cap to the time when cannons fired only round, lead balls. A “3-pounder” cannon fired a ball weighing exactly 3 pounds. Early muskets were designated similarly.

It quickly became obvious that calling a gun having a bore such that 12 lead balls made one pound a “one-twelfth pounder” was a bit awkward. A simple Number 12 was adopted. This is why early shells are headstamped “No. 12” for 12 gauge, “No. 16” for 16 gauge and so on. Winchester-Western continued the practice into the plastic shell era. The British and others later changed this to “12 bore,” while another following developed for “12 gauge.”

The 20 bore, 20 gauge, or whatever you want to call it, has a bore diameter of exactly 0.615 inch. Of the many guns I have measured over the years using a dial gauge on the entire length of barrel, diameters ran from 0.615 to 0.619 inch on quality arms. Inexpensive single shots vary all over the place, from 0.618 to 0.635 inch.

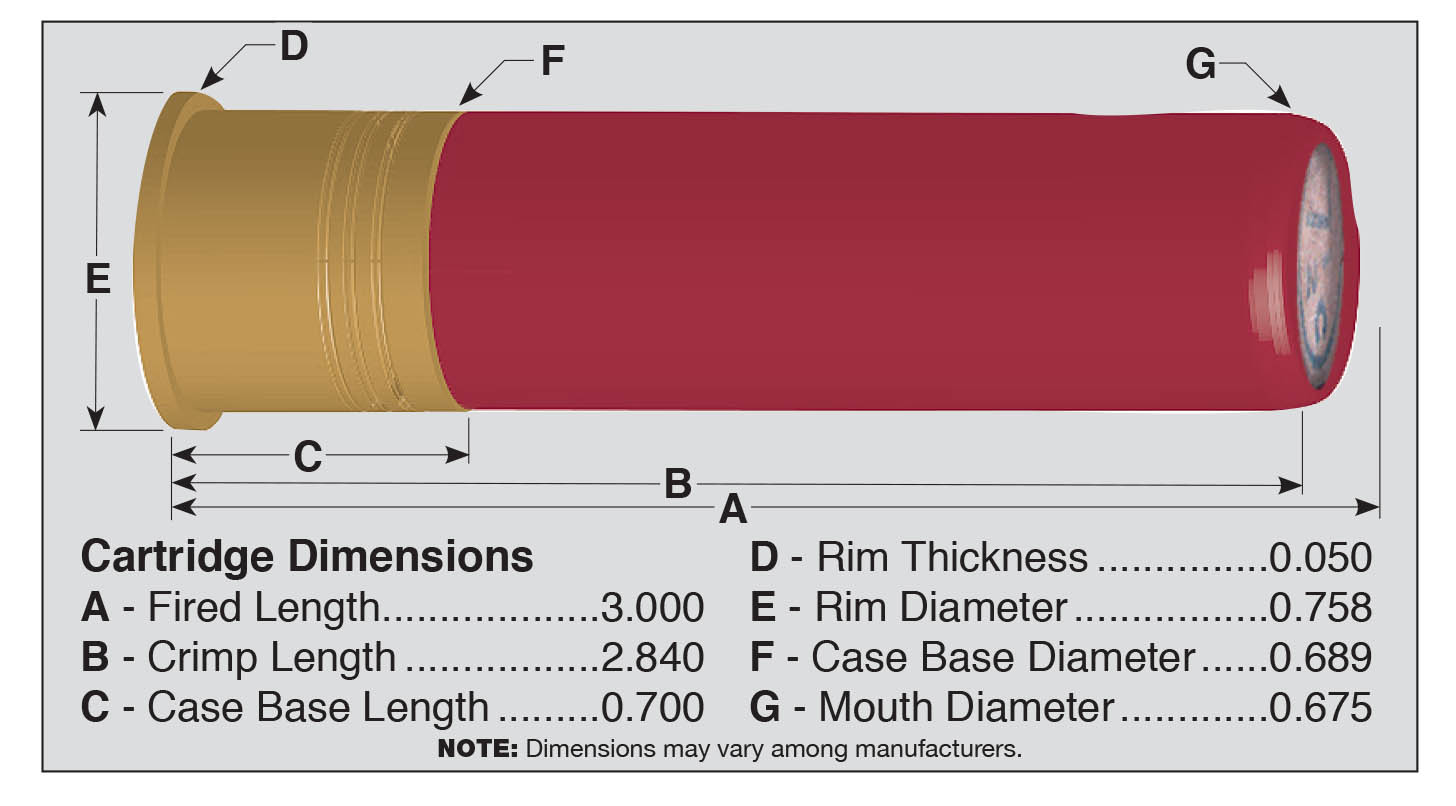

We now come to the 3-inch 20 gauge – with no use of the word magnum. That word appeared in the eighteenth century and referred to wine bottles of greater than normal capacity. Its meaning is the same when applied to cartridges, but such use is quite recent. Three-inch cases scale this length from base to mouth of a fired cartridge. Standard 20s measured 2.75 inches beginning about 1930 and 2.5 inches before that. Date of introduction of the 3-inch 20 gauge? Well, that depends.

During the muzzleloading era, it was possible to use any amount of powder and shot desired, since both were poured loosely down the bore. The British did a lot of experimenting and determined that what was often called a square shot charge (height of the charge equaled bore diameter) gave the best results. In the 20 gauge this was 3⁄4 ounce. Also, the most efficient black-powder charge was one that equaled the shot charge in volume, not weight. By use of a ballistic pendulum, velocity of these loads registered about 1,050 fps in muzzleloaders.

With the coming of self-contained cartridges, the foregoing rules remained pretty much unchanged. In America there was a tendency to increase powder and shot charges a bit, but only in 12 and 10 bores. As the transition to smokeless powder began, strange things happened.

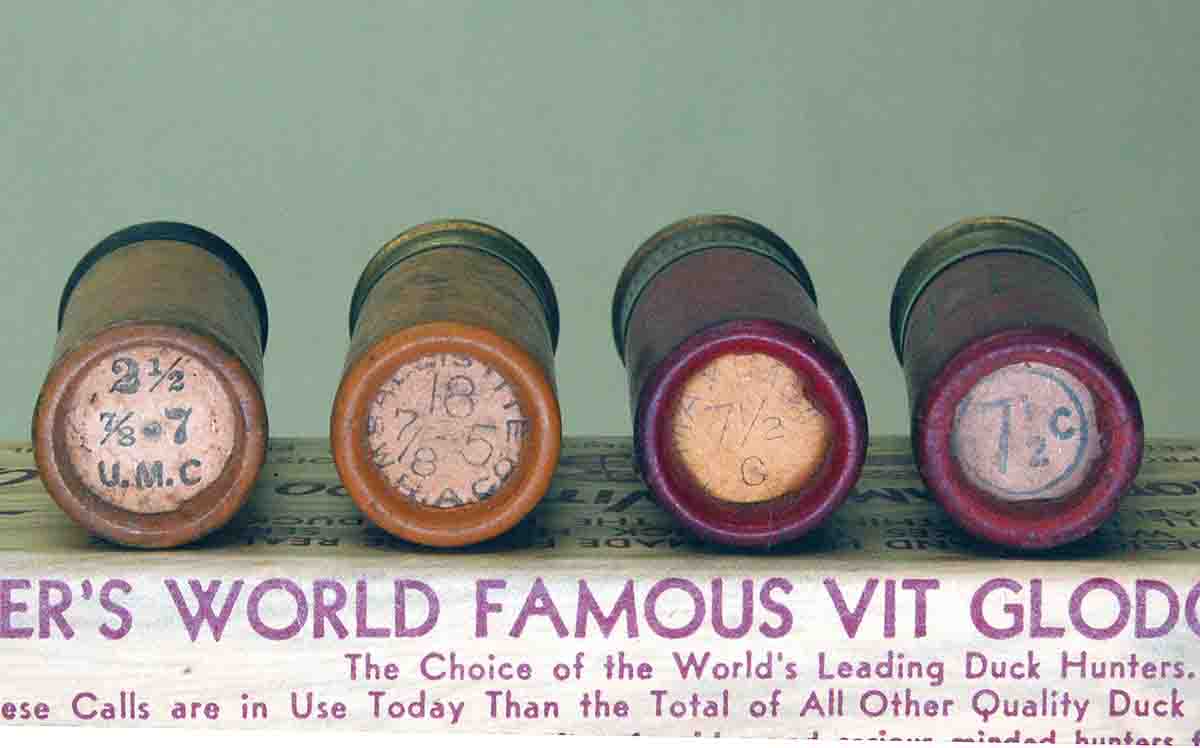

The new, dense smokeless powder took up far less space in the shell than black powder (as opposed to bulk smokeless, which loaded volume-for-volume with black). Extra space was, for some reason, quickly taken up by more shot. By 1900, for example, Winchester offered a 7⁄8-ounce 20-gauge smokeless load at the same velocity as its relatively new 3⁄4-ounce smokeless load, which in turn duplicated the company’s standard (and only) black-powder 20- gauge cartridge. Then in 1901, Winchester listed “23⁄4 inch and longer” empty cases available for handloading. At the time the 20-gauge case was 2.5 inches long prior to crimping.

By 1907 Winchester was offering a special order 3-inch case containing 7⁄8 ounce of shot but with enough powder to give an increase of about 65 fps over the 2.5-inch load of 7⁄8 ounce of shot. Given that the 20 gauge had always been considered a “kid’s gun” for ambushing rabbits, squirrels and any edible bird “on the sit,” of what possible use could a special, faster loading be? Now things got even stranger.

By at least 1908, the famous firm of Parker Brothers, makers of American side-by-side doubles, was producing a heavier 20-gauge shotgun chambered for 3-inch shells. Some company advertising – and some of what was considered the sporting press at the time – was saying that the smokeless 20 gauge was the equal of the black-powder 12 gauge. Also, added velocity produced by the 3-inch load was giving an amazing increase in killing powder to its 7⁄8-ounce shot charge. Uh-huh?

The vast majority of shotgunners totally ignored this silliness. A tiny group, however, took it to heart. They were members of the exclusive “duck clubs” prevalent in many parts of the country until about World War II. Not only were the long-chambered 20s considered extremely effective but also very sporting. Use of such a shotgun allowed a hunter to join the ranks of the “crack duck shots” who killed 40 to 50 birds per day. In fact, these specialty shotguns, which weighed from a half to over a pound more than ordinary 20 bores and sported 30- or 32-inch barrels, were often called duck club guns.

While the long 20 could in no way be considered popular, it generated a steady interest. Most surprising was the 1911 introduction by the J. Stevens Arms Co. of its Model 200 pump gun. This was the first 20-gauge repeating shotgun, and it was chambered for 3-inch shells! By 1918 Remington was listing the long 20s under “Special Shells” ammunition, but no specific loads were given. In 1922, A.H. Fox Gun Co. shipped its first 20-gauge, 3-inch Super Fox double, a heavy-framed, thick-barreled model originally chambered for 3-inch, 12-gauge shells. Fox records show these 20s could weigh up to 81⁄4 pounds!

From all that can be determined, it appears there was a large “Look what I have that you don’t!” factor. As for the duck shooting end of it, I grew up a couple of miles from the Mississippi River and had shot my share of ducks both over water and in cornfields. It is a simple fact that 11⁄8 ounces of chilled No. 6s from a properly directed full-choke 16 gauge, or 11⁄4 ounces of the same from a full-choke 12, will kill every duck that ever fluttered into a decoy spread with head up and feet down at 25 to 40 yards. Also, if one was a good shotgun operator, many of the birds would have more holes in them than necessary. Then, too, this was in the very late paper-shell era. Those 75-percent-plus patterns one read about were largely shot with typewriters! Nevertheless, the 7⁄8-ounce charge of the 3-inch 20 (one ounce after about 1925) would have been almost as effective.

Unfortunately, many who wrote about the early 3-inch 20 favored No. 7 shot, saying that ducks either came down dead or were “cleanly missed.” This tells us without a doubt that the birds were decoyed and fairly close. As for the “missed” ducks, many weren’t missed but flew off to die. The small shot sometimes didn’t penetrate deeply enough due to thick feathers or could not break heavy wing bones to bring ducks down at the shot. The long 20 should have died, but it didn’t. Next time we will see what it has become today, and it’s not pretty.