Duplicating Factory Ammunition

Sometimes the reward is worth the work.

feature By: John Barsness | April, 17

Eventually the price of chronographs started coming down. I purchased my first from a now-defunct company in 1979. Considering inflation, it cost about the same as an Oehler 35P or Labradar today, something of a stretch for a college student but far less than the chronographs used by ammunition companies.

Like many chronographs back then, “reading” velocity involved turning a knob around a numbered dial: If a light lit up next to a number, you recorded that number. A complete turn of the dial resulted in a multi-digit number, which was not velocity. Instead you looked up the number in a booklet, which converted it to velocity. The process was slow but did result in non-fiction.

The first ammunition chronographed was some .22 Long Rifle loads. The results came very close to factory-listed velocities, so I chronographed some handloads. This could have taken all day, except I only owned three centerfire rifles: a pair of Remington 700s (.243 and .270 Winchesters) and a sporterized 1903 Springfield with the military .30-06 barrel.

Only the .30-06’s handload, a Nosler 200-grain Partition combined with Hodgdon’s original mil-surp H-4831, duplicated the

This could be attributed to differences in individual rifles, but my .243 Winchester had a 22-inch barrel, the same length as on the Winchester and Ruger 77 test rifles in Speer’s 9th and 10th manuals. My handload also used exactly the same combination of components: Speer 105-grain Hot-Cor spitzers, Winchester cases, CCI 200 primers and IMR-4350 powder. In my Remington, 41.5 grains grouped best, and both manuals indicated muzzle velocity should be slightly under 3,000 fps. Instead it averaged slightly under 2,800.

My primary .270 load used the Hornady 150-grain Spire Point and 58.5 grains of H-4831. Hornady’s recent manual listed 58.9 grains as maximum, for 3,000 fps from a custom FN Mauser with a 24-inch barrel. I expected somewhat slower velocity with .4 grain less powder from my rifle’s 22-inch barrel, but not 2,850.

I then clocked a few leftover rounds of factory ammunition. Winchester 100-grain .243s got about 2,800 fps instead of the advertised 2,960, and Remington’s 130-grain .270 Winchester load averaged around 2,700! While a Remington 180-grain .30-06 load ran the traditional 2,700, a Winchester 150-grain load averaged 120 fps slower than the advertised 2,970. This shouldn’t have been surprising, because the Speer Number 6 manual listed the chronographed velocities of a bunch of factory ammunition. Velocities were all over the place, though usually slower than advertised, partly because, back then, most factory “test barrels” were 26 inches long.

Looking back across nearly three decades, however, I realize the differences didn’t matter much. All the ammunition, both handloaded and factory, had taken big game without any problems. Back then few hunters ever shot big game much beyond 300 yards (something still true today), and most of my handloads matched actual factory ballistics.

That chronograph lasted a decade before the circuitry failed. By then the company had gone out of business, but chronographs costing a quarter as much had appeared, featuring digital readouts instantly appearing after each shot. Average shooters could now afford easy-to-use chronographs, so factories had to start making ammunition that came close to advertised velocities – and also made some producing above-normal velocities.

In fact, since around 2000, I’ve chronographed some factory ammunition showing the signs handloaders have long used to guesstimate excessive pressure, including hard bolt lift, extremely flat primers and ejector-hole markings on case heads. All of these can be due to reasons other than high pressure, but when they occur alongside really high muzzle velocities, something might be up. One brand of high-velocity 180-grain .30-06 ammunition, advertised at 2,880 fps, chronographed over 2,950 from the 24-inch barrel of one of my .30-06s – and blew a primer in a friend’s rifle of the same make. We sent the remaining ammunition back to the factory for testing. They reported pressures were “normal,” but the load was quietly dropped a few years later.

During the same period, accuracy of factory ammunition also improved considerably. Most improvement was probably due to better bullets and rifles, but I’ve also seen another factor at work: New brass is often straighter than cases resized in a typical full-length die, where the expander ball can pull the neck out of line with the case body. New-brass forming is done in a die resembling a typical full-length loading die without the expander. Unless the forming die is worn by overuse, the necks of new cases come out very straight, so bullets tend to be seated straighter than in resized cases.

When some handloaders chronograph a zippy factory load, they’ll disassemble a round, hoping to come up with a match for the powder charge. This can help, but other than Alliant “dot” powders with colored particles mixed in, powders can’t be positively identified by appearance, and most used in factory rifle ammunition aren’t available to handloaders anyway.

The powders we buy are normally blended from different manufacturing lots, to ensure reasonable consistency in burn rate. Most ammunition factories buy unblended powder that can vary considerably from batch to batch, in cardboard barrels the size of 55-gallon drums. They can afford to use a pound to work up a new load, but don’t take nearly as long as the typical handloader, since they normally have an indoor range with pressure-testing equipment and often an electronic target.

On my first visit to a major ammunition factory years ago, one of the ballisticians demonstrated “working up” a .270 Winchester load, using powder from a barrel labeled in a number unknown to hand- loaders. It took less than an hour to arrive at a new powder charge for hundreds of thousands of rounds.

Over the past few years I’ve tried several new powders that can add at least 100 fps to certain cartridges, at safe pressures. However, note the listed loads often use older powders, because some have worked great for the purpose for many decades – and I don’t really want a 270-grain .375 H&H load going much faster than 2,700 fps.

These days I spend quite a bit of time range-testing data for newer powders. The testing is often done in a wide range of temperatures, because some new powders designed to produce higher velocities can vary considerably in cold or hot weather. If either is a factor in your shooting, then some powders aren’t going to work as well, but the good news is more newer powders are also designed to work more consistently at varying temperatures. (An article on this subject will appear in an upcoming Handloader.)

Some factory ammunition uses canister powder, making duplicating factory loads much easier. In 2006 I acquired a Weatherby Mark V Ultra Lightweight .240 Weatherby Magnum, along with some Weatherby ammunition for testing and cases to handload. The most accurate load grouped Nosler 100-grain Partitions into much less than an inch at 100 yards, though muzzle velocity was over 200 fps slower than the advertised 3,406 fps.

Unfortunately, none of my early handloads shot as well. Norma loads Weatherby factory ammunition, so I broke down a couple of rounds, finding 51.0 grains of an extruded powder. Norma’s load data for the 100-grain Partition showed charges of MRP (Magnum Rifle Powder) ranging from 50.0 to 53.0 grains, and the powder in the .240 rounds looked a lot like my supply of MRP. The maximum listed charge of 53.0 grains beat the factory ammunition by about 100 fps and came very close in accuracy. Still, neither load came anywhere near 3,406 fps, and what’s the point of packing a “slow” Weatherby Magnum? So I ran a data search and found a .240 load using Accurate Magpro that pushed the Barnes 85-grain TSX 3,550 fps. I didn’t have either Magpro or 85-grain TSXs on hand but did have some Nosler 90-grain E-Tips and Ramshot Magnum, which in Western Powder’s data often shows velocities right alongside Magpro. Consulting the Ramshot staff resulted in an accurate load close to the advertised velocity of the 100-grain factory ammunition, but since the 90-grain E-Tip has a slightly higher ballistic coefficient than the 100-grain Partition, my load shot flatter and drifted less in the wind.

Nosler also often uses canister powders in its ammunition, because Nosler knows which brands work due to constant testing in its indoor lab for reloading data. I’ve had excellent luck with Nosler’s published data when duplicating factory ammunition, both with “standard” rounds and the new Nosler cartridges. In fact, the 140-grain handload for my .26 Nosler uses almost exactly the same charge of Hodgdon US 869 that Nosler used in its factory loads when the cartridge first appeared.

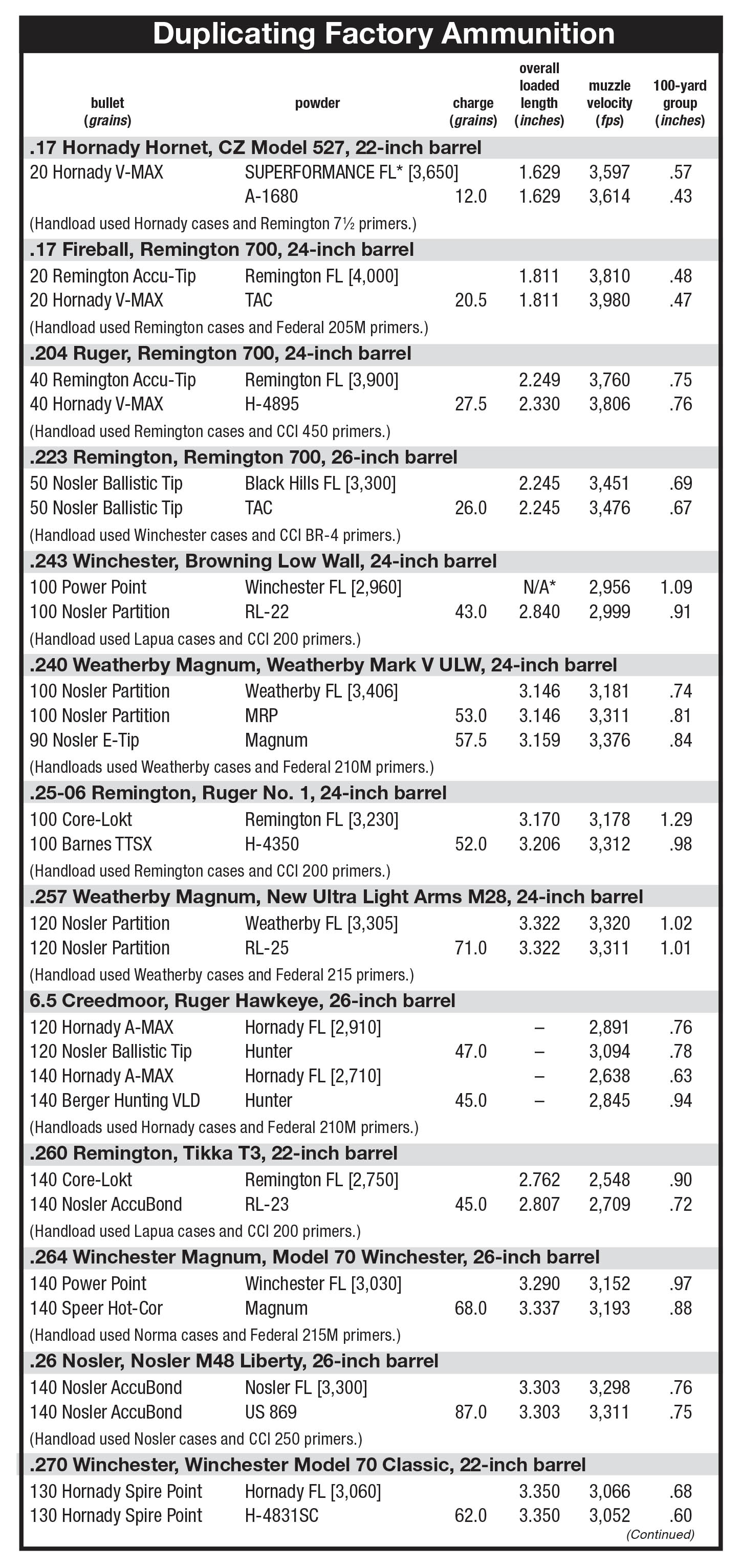

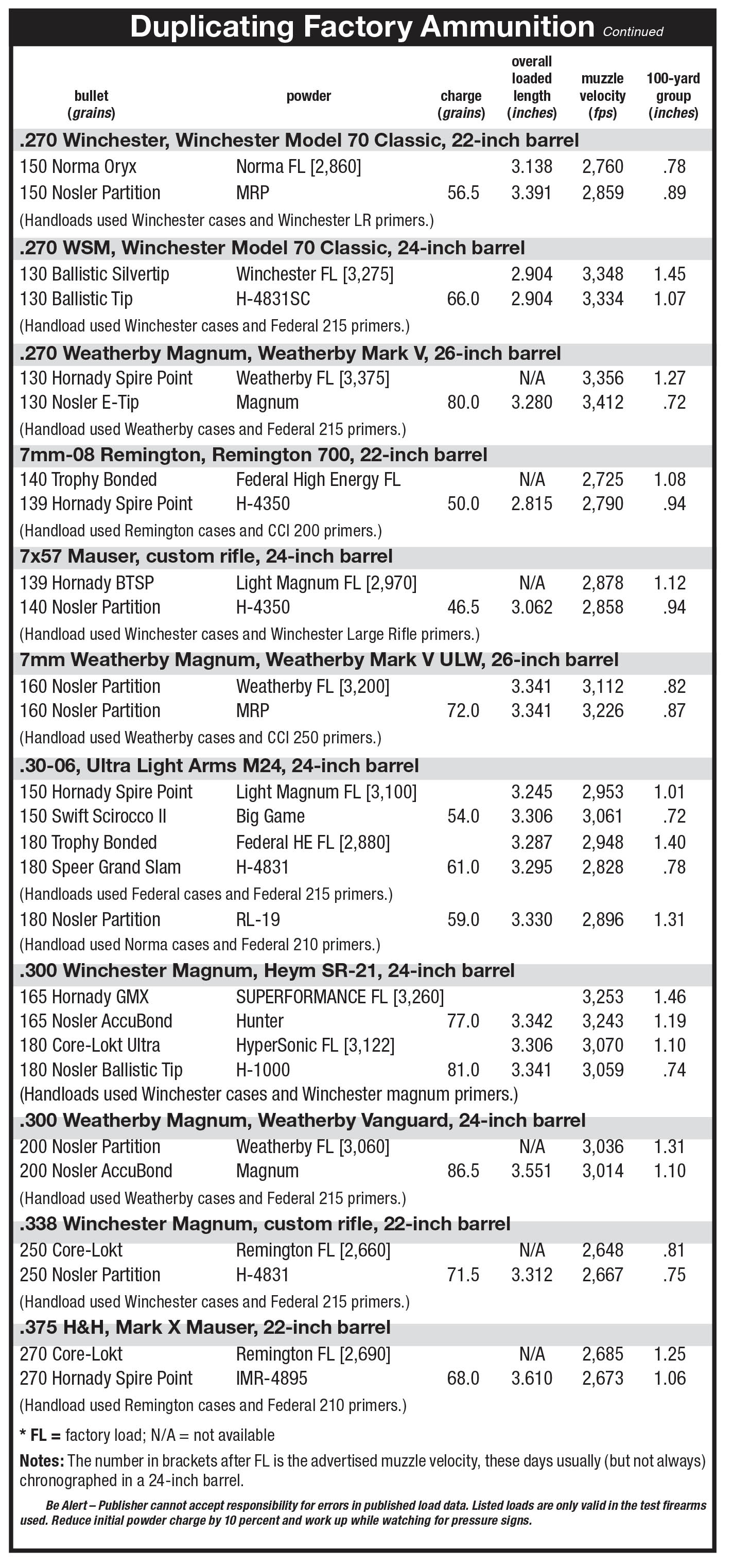

The loads in the accompanying list include others I’ve come up with over the decades to match – or exceed – the performance of factory ammunition. They include some discontinued factory loads, especially older “increased velocity” ammunition like Federal High Energy and Hornady Light Magnum, mostly as a basis for comparison. These days the same concept often appears under different names, such as Hornady Superformance and Remington HyperVelocity.

This ammunition used to be difficult to match by handloading, but with the abundance of new powders these days it’s often pretty easy. It should be noted, however, that Hornady Superformance ammunition is not always loaded with the same SUPERFORMANCE powder sold by Hodgdon. Instead Superformance ammunition is loaded with different blends, exactly which depending on the cartridge, and the SUPERFORMANCE powder sold by Hodgdon is the blend used in the .30-06 and a few other rounds.

I mention this because a reader once complained about an article where I’d listed the excellent results from SUPERFORMANCE powder in the .30-06, but said SUPERFORMANCE powder didn’t come anywhere near factory velocities in his .17 Hornet. I knew he hadn’t looked up the powder charge, because while Hodgdon lists considerable data for SUPERFORMANCE powder, there isn’t any for the .17 Hornet. Instead he’d broken down a factory round and weighed its powder charge, then tried handloads with the same amount of SUPERFORMANCE canister powder. Since the canister blend is far slower-burning than any powder suitable for the .17 Hornet, the velocity was very low, so he assumed I was a nitwit. Sometimes I can be, but not in this instance.

The listed handloads all use either published data or unpublished guidelines provided by powder companies. Several have the same overall length as factory ammunition using the same bullet. When I run across a factory load that shoots very well in one of my rifles, it seems logical to seat exactly the same bullet to the same depth. That usually works, despite many handloaders firmly believing that rifle bullets should always be seated “right off the lands.”

Some handloaders might find imitating factory loads a strange concept, especially those who remember when “store-bought” ammunition was considered second- rate. I believe in whatever works, especially techniques that save time when searching for a fast and accurate load.

These days some really good factory ammunition is relatively inexpensive, which brings up another question: Why spend hours in the loading room, when we could be out shooting factory stuff? But shooters almost never handload to save money. Instead we spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars on fancy equipment in the hope of making ammunition better than “store bought.” Sometimes we even succeed.