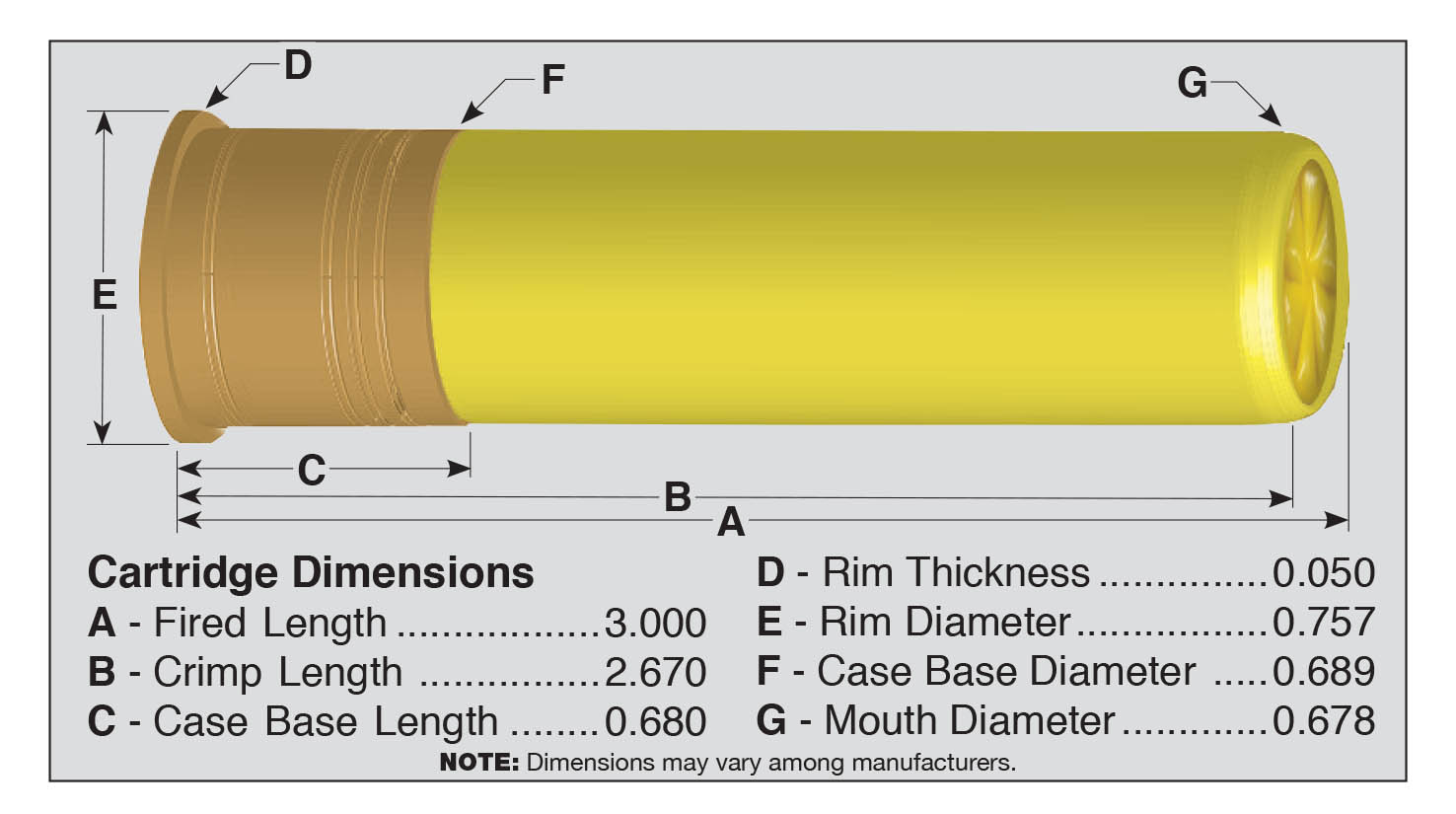

Cartridge Board

3-Inch 20 Gauge Part II

column By: Gil Sengel | June, 17

Unfortunately, the long 20 was not cashiered – due to a continuing interest/curiosity and the fact that there were a number of expensive double guns being used by “people who knew people” in the gun and ammunition business. Not only did Parker Bros. and A.H. Fox chamber these shotguns, but also Winchester offered the Model 21 with 3-inch chambers on special order from 1932 to 1949. Winchester chamberings included not only 12 and 20 gauges, but 16 gauge as well. At least Winchester and Peters loaded the roll-crimped ammunition. The 3-inch 16 had to have been the creation of someone looking for something to create!

Mercifully, the long 16 was quickly gone, but the 3-inch 20 gauge lived on. Folks with shotguns so chambered have written that Remington ammunition was available quickly after World War II, though this may have been old stock warehoused during the war. Remington did list one paper-cased 3-inch, 20-gauge load in its 1958 catalog. This was a 31⁄4 dram equivalent, 11⁄4-ounce loading of either No. 2, Nos. 4, 6 and 71⁄2 shot. In 1957, Western Ammunition showed two 3-inch loads. One contained 11⁄8 ounces of No. 6 shot and the other 13⁄16 ounces of No. 4s. No powder equivalent or velocity was given, but the shot was copper-plated Lubaloy brand. Not to be outdone, Winchester began carrying 3-inch 20s by 1960, the two loads listed being exactly the same as Western’s. Unfortunately, several factors were now coming together that would permanently alter the 20-gauge shotgun, and none of them were for the better.

The first item was marketing. When the .243 Winchester and .244 Remington were introduced in 1955, both were marketed as ideal all-around cartridges for varmints and deer. Own only one rifle, they said, for all the hunting that most folks do. Of course, it was necessary to buy a new rifle. An alert lad in someone’s marketing department then decided to apply the same logic to shotguns – and there was the 3-inch 20 gauge just waiting to be discovered. It was quickly labeled the 20-gauge 3-inch Magnum. “Ducks and geese in the morning, quail or grouse in the afternoon,” the ads said, all with the same shotgun! Just change shells.

Obviously, none of those enthusiastic folks had ever launched 11⁄4 ounces of shot from a 6-pound (or less) 20 gauge. It is a memorable event. The first time I saw it done was about 1960, when I was in maybe seventh grade. My cousin Robert was my age and got a new break-open single-shot 20 gauge for his birthday. It had a 3-inch chamber and couldn’t have weighed over 51⁄2 pounds. He brought it to our next rat shoot at the local dump, along with a box of shiny red, 3-inch paper-cased ammunition. (This was before 20- gauge shells were colored yellow.)

Soon a big rat appeared, and Robert snapped a shot at it. For a few seconds neither rat nor rat shooter moved. When he finally lowered the shotgun, Robert had tears streaming from both eyes, blood from both nostrils and a split bottom lip – the scar is visible to this day. The rat fared worse, but not by much. I was surprised how close the color of fresh blood matched that of those long, red shells.

At this time, a strong U.S. dollar made importing double guns from Europe (mainly Spain and Italy) profitable. Most of these were very good field guns with double triggers, plain extractors and a little engraving. At first, heavier magnum versions were offered in 3-inch 12 and 3-inch 20 gauges, but soon virtually all standard weight 20s had 3-inch chambers.

Maximum average pressure is the same for both 23⁄4- and 3-inch 20-gauge ammunition, and cartridges are seldom loaded to this ceiling. Recoil from the long shell, however, is unbearable in 51⁄2- to 6-pound guns. Also, stocks split behind the tangs if many heavy loads were used. The easiest fix was just to add weight to the gun, which was done to the tune of 12 to 20 ounces, mainly in the barrels. The dynamic, well-proportioned, affordably priced 20-gauge double was no more.

The 1970s saw Remington keep its one 3-inch, 20-gauge load, but Winchester added a 11⁄4-ounce load of buffered Nos. 2, 4 or 6 shot, plus a nonbuffered load using Nos. 4, 6 or 71⁄2 shot. In the 1980s both makers added one steel shot loading for waterfowl.

By the turn of the century, Remington had one steel load, one buffered 11⁄4-ounce load of No. 4 or No. 6 shot and a 11⁄4-ounce copperplated No. 6 “turkey load.” Winchester had similar offerings and even a cartridge containing 24 pellets of No. 3 buckshot.

Today, factory load listings are even greater. Winchester shows five with lead and nine using steel shot. Fiocchi lists nine lead and three steel loads. Remington no longer puts out many catalogs, so no one knows. Federal, however, takes top honors with 15 combinations, plus one carrying 18 pellets of No. 2 buckshot. Smaller outfits load various forms of nontoxic shot and lead shot to very high velocities.

Modern factory loads are really intended for use in newer autoloaders, all of which are a bit heavy but do control the recoil well – if not the muzzle blast. Even if some of this ammunition can be found when needed, it’s hard to understand why anyone would want a 20 gauge for waterfowl or turkeys, as the guns aren’t carried much. Larger bores weigh little more and pattern more uniformly.

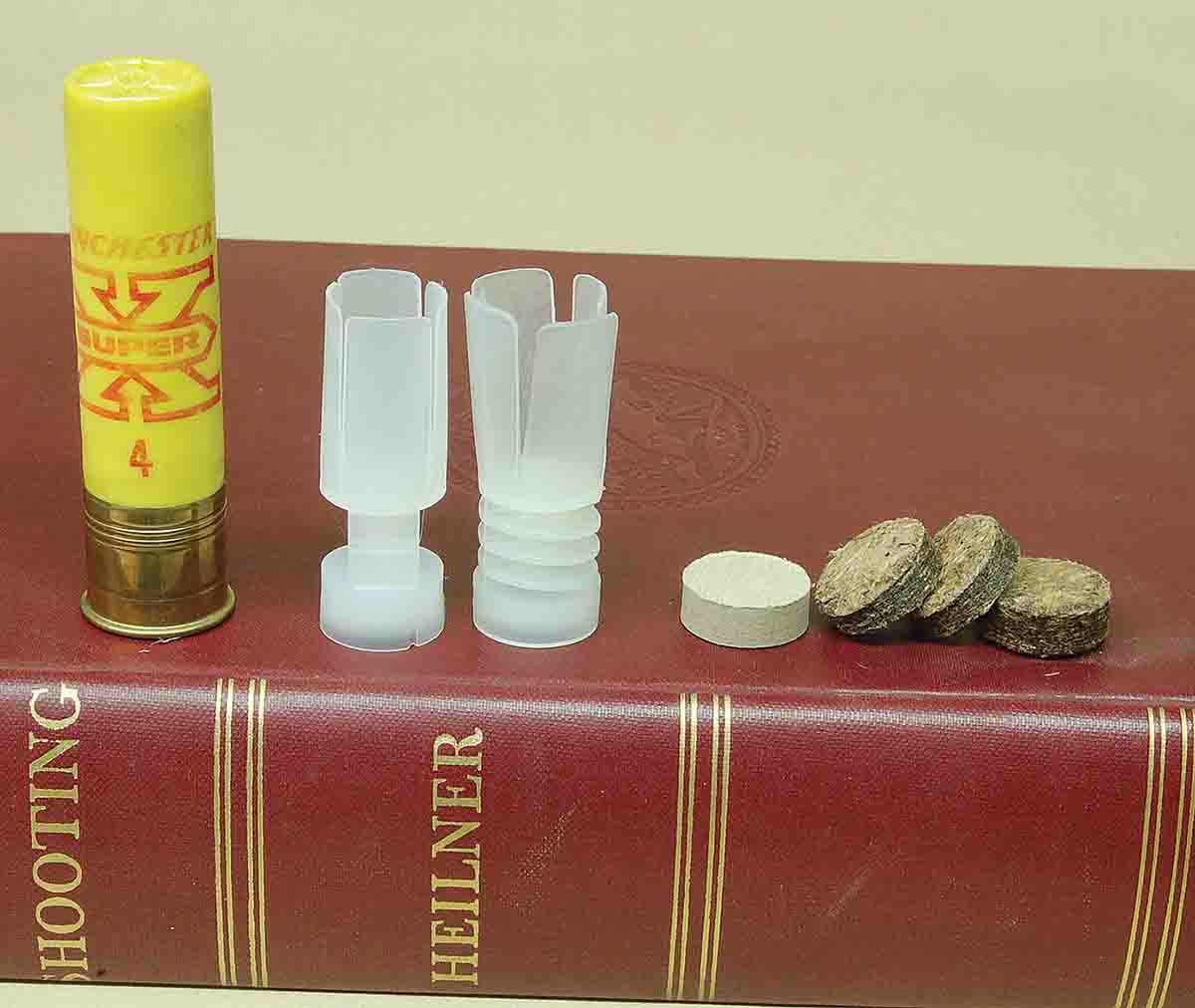

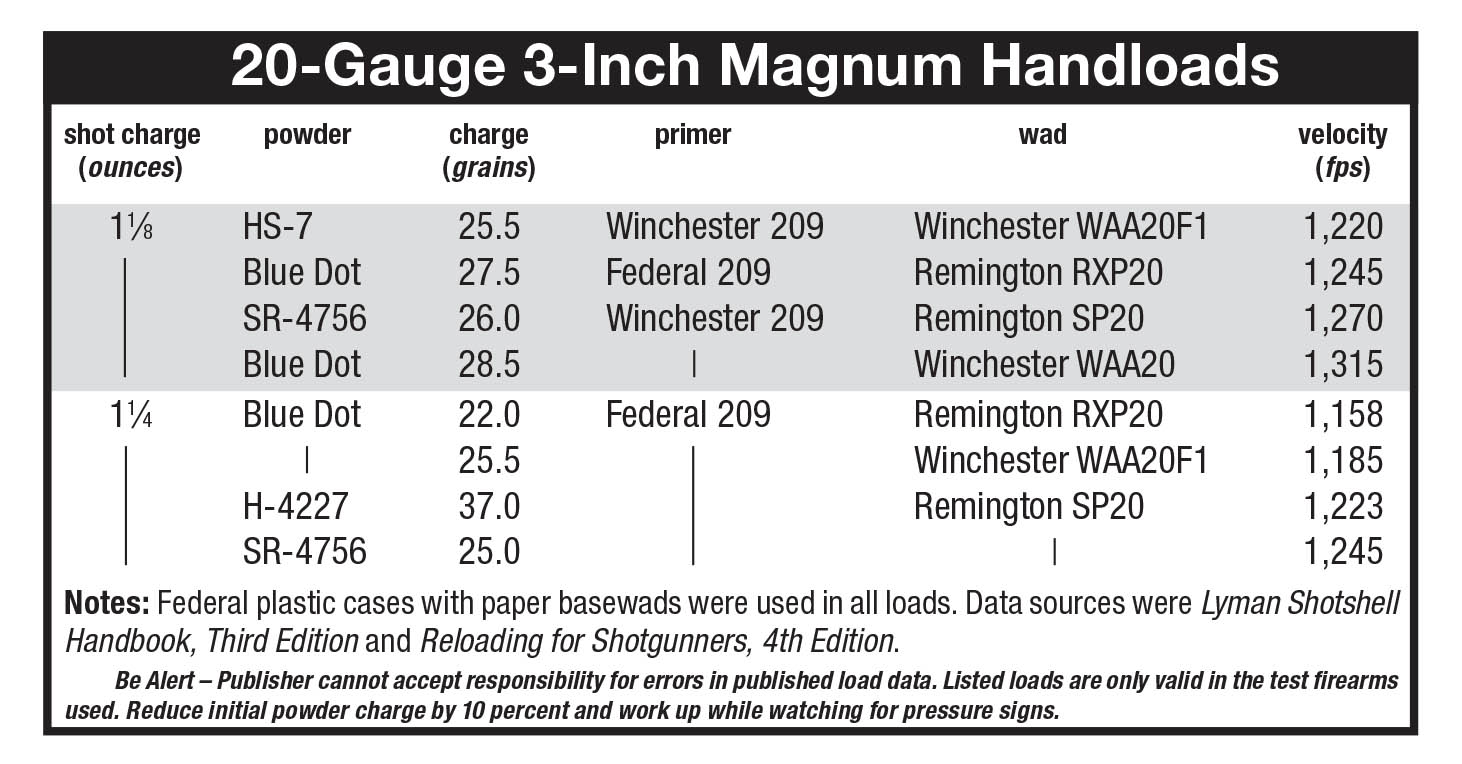

Nevertheless, if one has a lead shot use for the 3-inch 20, it will soon be discovered that it responds to handloading better than any other smoothbore except the 3-inch .410. Varying shot size, hardness, velocity, powder and wad brands radically affect patterns as shot weight goes up and bore size shrinks. Federal, Fiocchi and Cheddite all sell new 3-inch plastic cases, so there is no need to shoot up expensive factory ammunition for empties.

The lead shot loads shown nearby have been fired in three shotguns over the years. All produced uniform patterns with good centers out to 45 yards. Yet my pattern notes show equal results from most 16- and 12-gauge guns throwing the same shot charge from commonly available factory shells.

Since the advent of virtually all 20s being cut with 3-inch chambers, hunters who want a very light, short-chambered 20 for 3⁄4- to 7⁄8-ounce loads of shot must buy new custom doubles costing well up into four figures. Many have turned to the 28 gauge, but that may not last. Recently announced was – you guessed it – the 3-inch 28 gauge. We all know how that will probably turn out.