Sierra Bullets

Accurate and Field Proven Since 1947

feature By: Terry Wieland | June, 17

For as long as I can remember, the name “Sierra” has been synonymous with high-quality bullets. Going back 60 years, when there was only a handful of independent bullet makers in the country, if looking for accuracy, you looked to Sierra. The Sierra MatchKing was the standard, and everything else was measured against it.

As interest in benchrest shooting grew through the 1960s and 1970s, any bullet maker aiming to break into the accuracy game knew it would not make it until it could take on the MatchKing and win its share of matches. Which, truth to tell, a few did. This caused Sierra to redouble its efforts, and it usually came back to regain its crown. Either way, the Sierra reputation for accuracy was never tarnished, and it was never out of the running.

In some ways, this reputation for accuracy has put the company’s extensive line of game bullets in

the shade. This is both unfortunate and unfair. The Sierra GameKing is one of the all-time finest all-around hunting bullets. It combines dependable accuracy with terminal performance – all anybody needs most of the time in the vast majority of cartridges.

These days, with allegedly “premium” hunting bullets popping out of the woodwork with alarming regularity, it pays to look at exactly what “premium” means, and then ask if you need to pay $5 a bullet for that performance – always assuming it will deliver it in the first place. By the original definition, a premium game bullet was one that would be used on tough animals and hold together dependably at high velocities – nothing more, nothing less. At Weatherby velocities, for example, conventional bullets had a habit of coming apart on impact and failing to penetrate. If hunting elk with a .257 Weatherby Magnum, you needed something like the 115-grain Trophy Bonded Bear Claw. At 3,200 fps, it was devastating on large animals – expanding beautifully, retaining almost all its weight and penetrating to the utmost.

In 1990, I took that combination to both Tanzania and Botswana. Everything went well, most of the time. Then I shot an impala at 100 yards. The bullet went between the ribs on both sides and exited without expanding. We chased that impala for an hour through the long grass and finally got it. Then I realized I would have been much better off in that situation with a conventional bullet that would expand even when encountering minimal resistance. It was a valuable lesson: Even the best premium game bullet is not always the best choice.

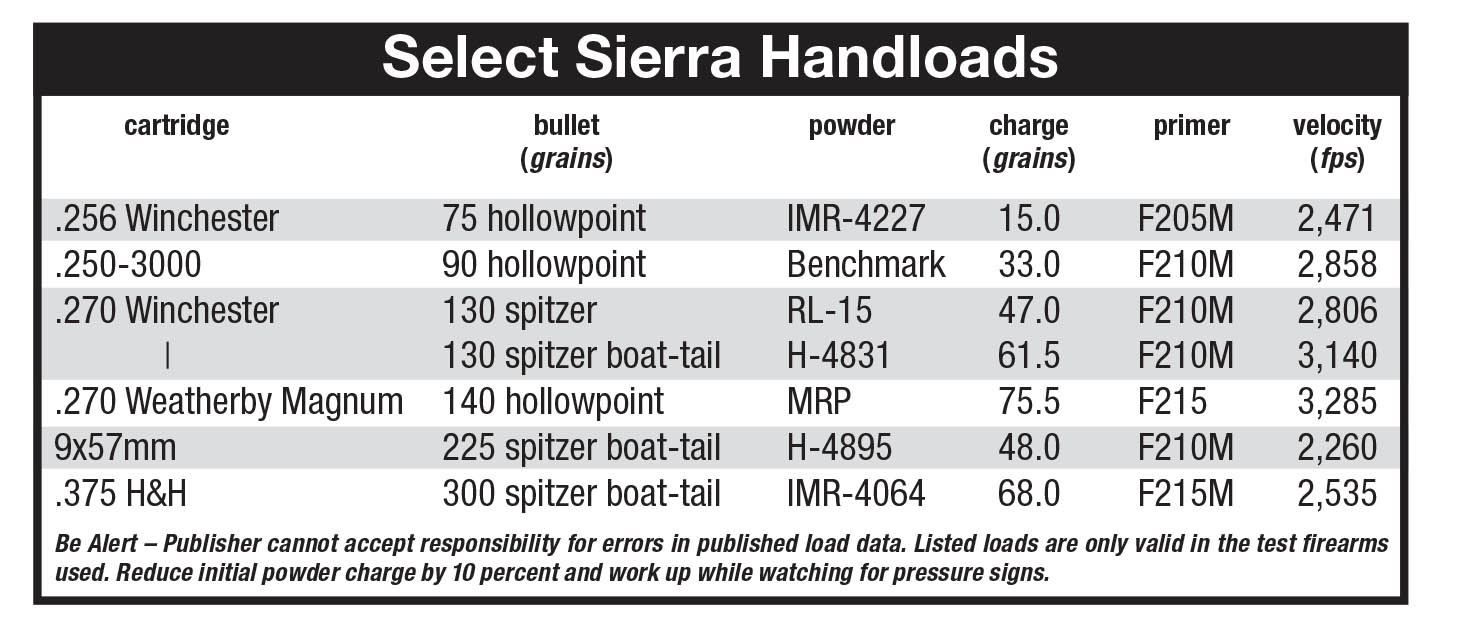

A couple of years ago, I was asked to develop a mild hunting load for the .270 Winchester for a friend’s wife. We wanted a 130-grain bullet at about 2,800 fps. It’s not always easy to find a bullet that is accurate at lower velocities, but the Sierra 130-grain Pro-Hunter turned in consistent five-shot groups smaller than an inch. We knew it could be relied upon to expand at those velocities out to 250 yards, which was the practical limit the lady set for herself when hunting pronghorn. That load worked so well, I now use it for training as well as some hunting.

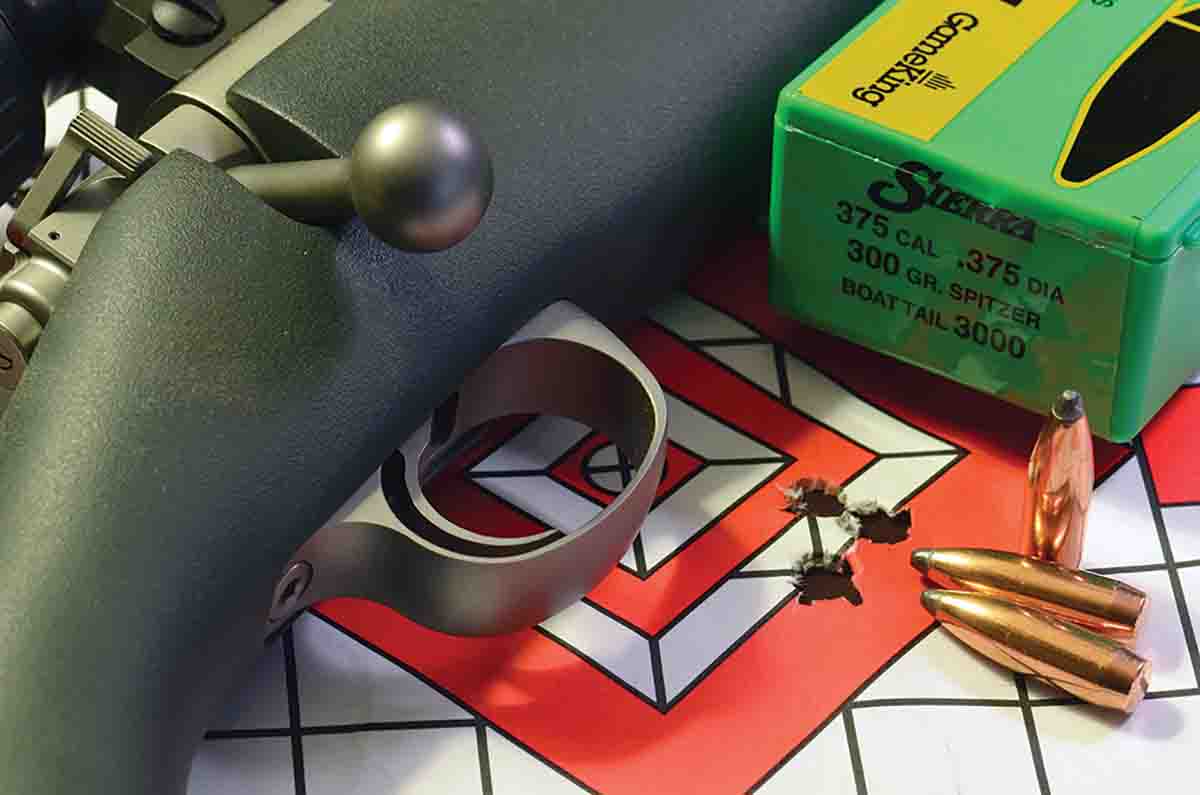

Last year, I needed a full-power load for a custom .270 Winchester, on short notice. I started with a proven load using H-4831 and three different 130- grain bullets that I knew to be good. My old favorite Nosler Partition, to my amazement, had the velocity but not the accuracy, while the Swift Scirocco II had high velocity but worrying pressure signs. The third bullet was the Sierra GameKing spitzer boat-tail, and it delivered both accuracy and a good velocity of 3,140 fps with pristine primers and cases. I used the Sierra load throughout the hunting season.

Interestingly enough, on three different shots, ranging from 103 yards to 328 yards, the bullet went right through the animal – more than enough penetration. One dropped on the spot, while the other two dashed a short distance and expired. The wound channels indicated the bullets all expanded well. The animals involved were two whitetails (a buck and a doe) and a Persian red sheep – all light-boned beasts weighing from about 125 to maybe 190 pounds.

Looking through my loading notes going back 30 years, I find that among the “best” loads for different cartridges, Sierra appears regularly: .250-3000 (90-grain hollowpoint), .270 Weatherby Magnum (140-grain hollowpoint), 9x57mm (225-grain spitzer boat-tail) and .375 H&H (300-grain spitzer boat-tail). All those are hunting loads.

Since early on, Sierra has offered a variety of bullet types for any given weight in a particular caliber. For example in .270 at 130 grains, there is both a spitzer flatbase and a spitzer boat-tail. I have rifles in which one performs better and rifles that prefer the other. Sierra has always offered hollowpoint big-game bullets as well, which gives shooters a third possible option in seeking that “perfect” load. Hollowpoints are unrivaled kings of the target ranges, and

Sierra builds proven accuracy into its hollowpoint GameKings. In hard-kicking rifles, these have the added advantage of not being deformed by battering in the magazine box.

Oddly enough, only one instance is found in my records where the hollowpoint version topped a spitzer, and that was in a .270 Weatherby Magnum many years ago. It delivered one full-power, three-shot group that measured .321 inch, and its five-shot groups were consistently under an inch. Wish I still had that rifle!

In the 1950s there were five notably independent bullet makers in the U.S.: Sierra, Hornady, Nosler, Speer and Barnes. Each developed its own niche in the market – Nosler with its Partition, Barnes with heavy-for-caliber bullets and so on. Hornady went on to become a full-service maker of brass, ammunition and loading equipment. Speer and Barnes both became part of conglomerates, and Nosler has ventured into brass, ammunition and even rifles. Except for a few glitches along the way, such as becoming part of the Leisure Group conglomerate in the 1960s, Sierra has remained independent, producing bullets and bullets only, focusing on making that one product.

Sierra grew out of a small general industrial firm created just after World War II, and its first bullet was the 53-grain .224, now known as the MatchKing. It came into being right at the beginning of the explosion of interest in benchrest shooting and became a mainstay – the bullet to beat by any other manufacturer that wanted to break into the game. In the 1960s Sierra expanded into pistol bullets and now makes a wide range of those as well. Today, there are almost too many noteworthy Sierra products to discuss individually. If the company has ever made a bad bullet, I am not aware of it.

One thing that should also be mentioned is the Sierra loading manual. While other manuals explain basic aspects of handloading, Sierra approaches the subject from the point of view of the serious long-range shooter and ballistician. The company was the first to publish not only ballistic coefficients for its bullets but also to provide different coefficients for different velocities. The ballistic tables provided in the early editions, and continued to this day, are unique in the field. For a while, the three-ring, binder-style manual (a godsend for those of us who like their manual lying open on the bench) was expanded into two volumes, one for rifles and one for pistols. It is now back to an all-inone volume. Sierra was also one of the first to embrace the computer revolution, with loading software and loading information on DVDs.

Although Sierra was founded in California and operated there for 43 years, it moved to Sedalia, Missouri, in 1990. This was due to California’s increasingly antibusiness, antigun stance. Missouri offered not only a better tax structure but also an environment that may well be the most gun-friendly in the country. Missourians love guns, and they love shooting at all levels. Where better for a bullet company to be located?

Venturing Into Ammunition

During its 70-year history, Sierra has never produced ammunition itself. Beginning in the 1970s, approximately, some ammunition companies began loading specialty bullets in their premium lines. Norma and Weatherby had led the way in this, but Federal was not far behind. Among others, Federal loaded Nosler Partitions and Swift A-Frames; in its match ammunition, it began loading MatchKings and the green “Sierra” on the box denoted fine accuracy.

Other ammunition makers have also loaded Sierras in their match ammunition. Now, Hunting Shack Munitions (HSM) of Montana is loading Sierra GameKing bullets in a line called, not surprisingly, Game King (sic). As well, it is doing something that is long overdue: offering a line of low-recoil hunting ammunition in such calibers as .270 Winchester, .30-06 and .300 Winchester Magnum.

Low-recoiling hunting ammunition is useful, because it allows a person who is new to the game, and might or might not want to continue, to use a powerful rifle without being frightened off by it. How many times have you heard someone talk about trying to teach his wife or young son to shoot with his hunting rifle and having the recoil and muzzle blast terrify them into flinching, missing and totally losing interest? This was exactly the reason for my developing the low-recoil .270 Winchester load mentioned earlier. Not all of us have a variety of hunting rifles to choose from, and few of us want to invest in a new, less powerful rifle just to teach someone who might lose interest.

HSM’s low-recoil ammunition is not merely light practice loads (although it could be used that way) but loads that tame a .270 Winchester down to the level of about a .257 Roberts, or turn a .300 Winchester Magnum into a ro-

bust .30-06. HSM states that recoil is reduced 53 percent over normal ammunition. For non-handloaders, these loads also provide a wider range of choice in hunting ammunition. For many hunting purposes, the power of a no-holds-barred .300 Winchester Magnum is not necessary, and this gives a more comfortable alternative.

In test shooting with a randomly selected rifle in three calibers (.270 Winchester, .30-06 and .300 Winchester Magnum), the felt recoil was, as advertised, much more comfortable; they delivered approximately the velocities in-

dicated by HSM, and all shot nice, tight three-shot groups right around an inch or a little larger.

These were hunting, not match, rifles, and in my experience that level of accuracy is about standard for any factory load. If better accuracy is wanted, you have to handload and develop tailor-made loads for an individual rifle.

For 70 years now, Sierra bullets have been renowned primarily for their accuracy and fine hunting performance at a range of velocities. Now that performance is increasingly available to non- handloaders.