In Range

Wildcats

column By: Terry Wieland | August, 19

Somewhere in the dim, dark recesses of some long-forgotten book there has to be an explanation – or at least an initial use – of the term “wildcat” as it relates to homegrown cartridges. The word seems to have been around forever, like “featherweight.”

As best I can determine, featherweight originated in the boxing world, where it was in use as early as the 1860s. By 1910, it was being applied to lightweight rifles and has been used so liberally ever since that it’s almost as generic as aspirin or Kleenex.

We are now into an area so murky it’s like the age-old question of the chicken and the egg. The reason I brought it up at all is to wonder whether wildcats, at this point in history, have even the faintest reason to exist. Is any wildcat, old or new, now worth the time, effort and expense of trying to load the ammunition?

Something I have noticed at various sales and auctions over the past few years is that any rifle chambered for a wildcat cartridge will almost always bring but a fraction of one chambered for a factory round. Even then, it will only realize a reasonable price if it comes complete with brass and loading dies, or if it can be economically rechambered to something more readily available.

James Grant, the sage of the single-shot rifle in the mid to late 1900s, had many old actions rebuilt into so-called “modern” varmint rifles. Quite a few of these were in oddball or wildcat cartridges. He found out the hard way that, having invested time and money to have those rifles made, he rarely broke even when he tried to sell them.

Particularly, Grant mentioned a couple of .22-caliber R2 Lovells, as well as one with interchangeable barrels in .22 Jet and .256 Winchester Magnum. What they brought when he sold them was about what he would have realized for the actions alone, and he concluded that the actions were all the buyers really wanted. The .22 Jet and .256 Winchester Magnum are technically not wildcats, but guns were made in such small numbers, and factory ammunition produced for such a short time, they might as well be.

In the 1930s, when wildcatting really took off, there was some justification for it, especially in small calibers at high velocities. One of the best known was the .22 K-Hornet, which had several claims to fame. One, it was

Parker Ackley later took that technique to extremes with his endless line of “improved” cartridges – factory rounds that were blown out to give them (allegedly) greater velocity. Call me a heretic, but greater velocity is not always an improvement or even an advantage. Notice that his “improved” .30-06 was greeted by the shooting public with a deafening yawn, and I don’t believe that improved .270s or .308s are breaking any sales records.

Lysle Kilbourn’s K-Hornet was not a vast improvement on the original, since it increased case capacity by only a few grains and afforded additional velocity of 100 or 200 feet per second with a 45-grain bullet. Going to all that trouble and expense to push a 45-grain bullet at 2,800 fps instead of 2,600 does not seem like much of a gain, but perhaps it was in 1948.

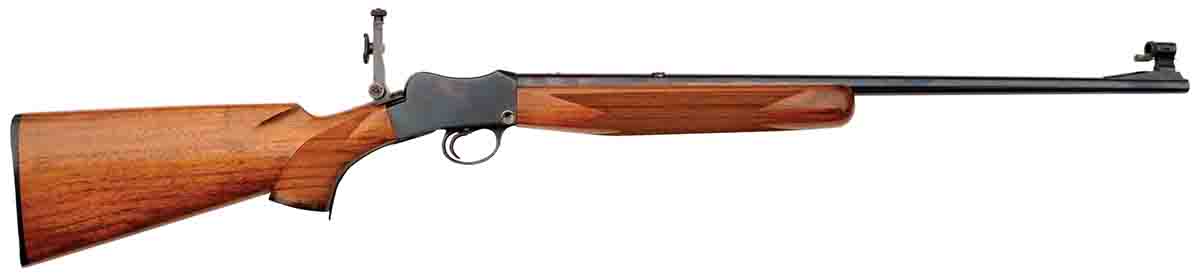

When buying a wildcat rifle, you may find you’ve purchased problems you never suspected. About 15 years ago, I was seduced by a converted BSA Martini that had been rebarreled to .22 K-Hornet. It had been customized by a semi-talented, semi-professional gunsmith. Judging by its appearance, this had occurred sometime in the 1960s. The barrel came from a Winchester Model 43 rifle, but that’s about where the positives end.

The difficulty with such a conversion is that the miniature BSA Martini was originally a rimfire, and while converting it to centerfire is not rocket science, it does need to be done right. Alas, such was not the case. Or at least, it may have been okay until I encountered my second difficulty, which was that I used some load data from the 1940s.

Handloaders in those days liked to live dangerously, and some of their loads are pretty hot. Unfortunately, around 1951 or ’52, ammunition manufacturers decided to strengthen Hornet brass with thicker walls and webs. This also reduced case capacity, which meant higher pressures with the same load. Whether this was widely published, I couldn’t say; Phil Sharpe did include a short notice to this effect in the supplement to a later edition of his Complete Guide to Handloading, but did not alter the load data in the front part of the book, which was based on old brass.

I was unaware of this but still backed off on the load to be on the safe side. Alas, I did not back off enough. Combined with modern brass, pressures were unseemly. It blew the centerfire conversion out of the breechblock, and locked the whole thing up tight. That was about 12 years ago. Since then, the rifle has visited four different gunsmiths, two of them twice, in cities as far apart as Pearland, Texas, and Ozark, Missouri. Only last month did I get it back from Lee Shaver with the whole conversion properly redone, and was able to fire factory Hornet ammunition without having to pound the action open.

If the advantage of having a K-Hornet is that you can fire factory Hornet ammunition, a major disadvantage is the brass cannot then be reloaded unless you have K-Hornet dies, and like most early wildcats, the dimensions of the K-Hornet were never standardized. Every gunsmith, it seemed, had his own version.

The list of wildcats extant today is mind-boggling, to say the least, but then so is the list of newly introduced cartridges that are said to be factory products. How many of those will still be chambered, with ammunition or brass still in production, five years from now? With many of these, handloading will become the only option if you want to keep shooting.

This brings us back to the original question: Are any wildcats worth the trouble? In my opinion, yes, but only because of the rifles themselves. There was a pre-war Winchester Model 54 for sale at a recent auction, rechambered for the .22 K-Hornet. Not being factory original, its collector value was minimal, but it was a really nice and historic rifle, nonetheless. Yes, I was tempted. No, I did not buy it. One K-Hornet has proven to be quite enough.