Propellant Profiles

IMR-4350

column By: Randy Bimson | October, 20

Purportedly at the time of its introduction, noted authority Phil Sharpe reported that DuPont developed IMR-4350 to optimize the performance of the only “magnum” cartridge of the time, the .300 Holland & Holland Magnum. True or not, with the introduction of IMR-4350, cartridges like the then-wildcat .22 Varminter (.22-250) and .25-06, the .270 Winchester and the .300 H&H Magnum, all of which would have been considered overbore capacity at the time, received a much heralded boost in performance from IMR-4350.

In the first “Propellent Profiles” review of IMR-4350 in 1970, John Wootters described it as a “landmark” powder (Handloader No. 27, September-October). IMR-4350 was a game-changer when it was introduced in 1940 and continues, 80 years later, to define the velocity and accuracy potential of many of the latest cartridge designs. IMR-4350 has become the propellant of choice of handloaders who find it a well-balanced powder for a broad selection of the “fat case, small diameter projectile” cartridges that have become, some more, some less, popular in more recent times. These include cartridges like the .22 CHeetah MKI & MKII, 6.5-284 Norma, 6mm and 6.5 Creedmoor, .270 and .300 Winchester Short Magnum, 7mm and .300 Remington Short Action Ultra Magnum and the .300 Ruger Compact Magnum.

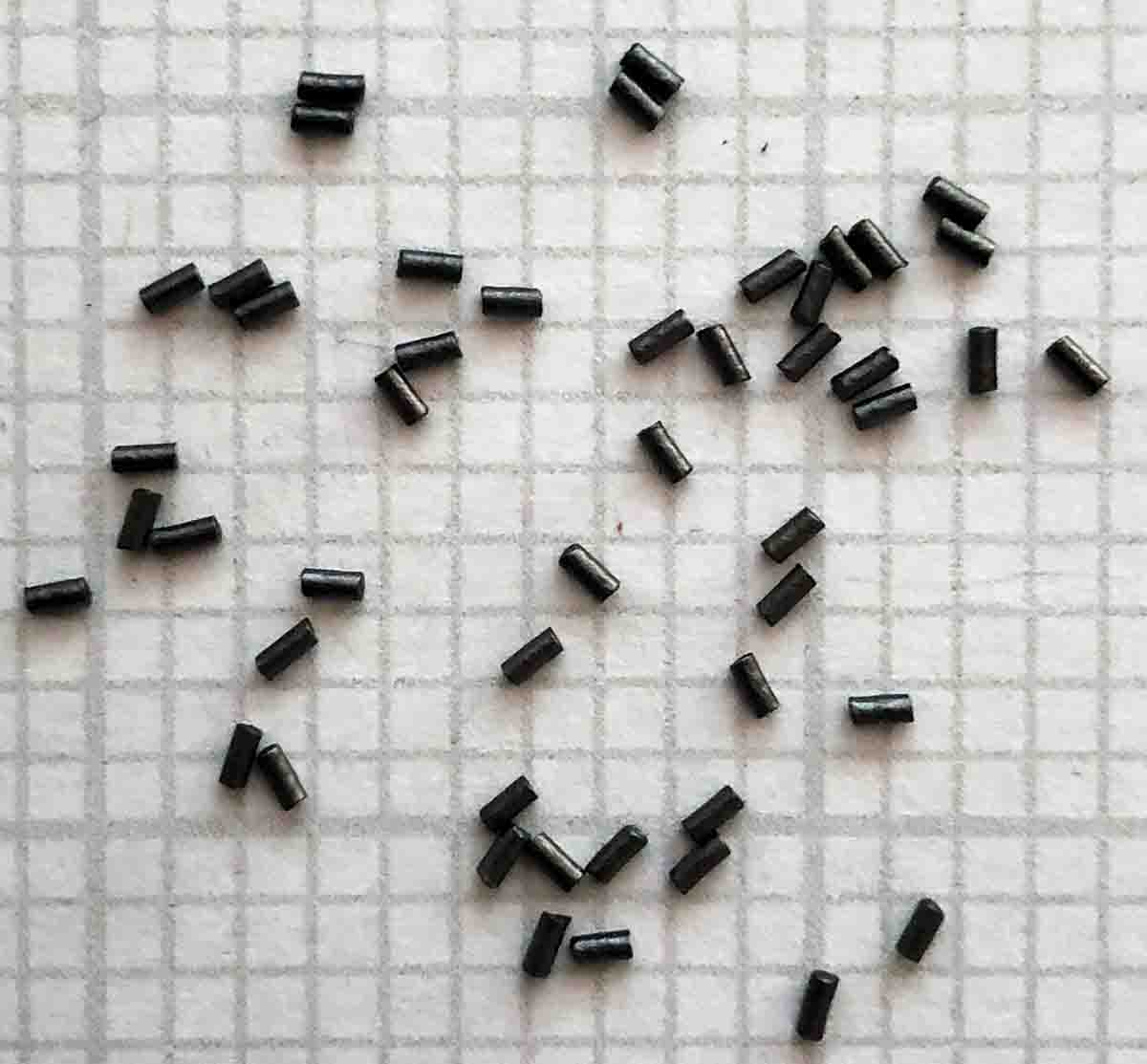

IMR-4350 is an extruded and longitudinally-perforated, long-grained, nitrocellulose single-based propellant. Its characteristics have changed little since its introduction, with the granular characteristics of current lot production being .083 inch in length by .038 inch in diameter with a hole diameter of .006 inch. The resulting web (grain wall thickness) is .016 inch. Bulk density is .945g/cm3. One of the very first so-called “progressive” burning powders, IMR-4350 incorporates a 6½ percent dinitro toluene (DNT) coating to retard burning. This aids in enabling IMR-4350 to produce high energy yields over a sustained period of burn time. Until the introduction of IMR-4831 in 1973, IMR-4350 had the slowest burn rate of the IMR series powders.

While cartridges using large charges of IMR-4350 benefit from the use of high-brisance primers like the CCI 250, Federal 215, Remington 9½M and Winchester’s LRM, most loading data for cartridges in the .22-250 to .30-06 range calls for standard large rifle primers.

Like IMR-4831 and other long grain powders, IMR-4350 can be a challenge for many powder measures to throw charges consistent enough to be agreeable to some handloaders. I am a notorious reloading tool junky and have owned no less than 10 different makes of powder measures. While I have not run IMR-4350 through all 10, I have three that stand out from the rest as being consistently capable of throwing charges of 65 to 73 grains of IMR-4350 within 2⁄10 of a grain. They are a Forster Products Bench Rest® Powder Measure, a Neil Jones Custom Products Micro Measure and an aged Belding and Mull “Visible” measure with a micrometer charge tube. The Belding and Mull has not been made for years, but I suspect the MVA “Visible” measure, an improved version of the Belding and Mull, would do just as well.

IMR-4350 has been used in my loads for more than half a century. Our “relationship” started off with a mutual liking for the .30-06 with assorted bullet weights and progressed through associations with the .270 Winchester, 6mm Remington, .22-250 Remington, .264 Winchester Magnum, 6.5-06, .280 Remington and the .300 H&H, among others. IMR-4350 never failed to produce excellent ballistics and equally good accuracy in any of the rifles I gave the time and attention to developing loads for.

I became infatuated with the .300 H&H Magnum in 1971, when through the efforts of an acquaintance, a standard grade pre-64 Winchester Model 70 became available. My reloading records show “Brutus,” as the Model 70 was so named by one of my longtime hunting companions, having consumed six pounds of an eight-pound canister of IMR-4350 (lot number P86MY07A). That rifle shows a distinct penchant for 68 grains of IMR-4350 topped off with either the Sierra 165-grain GameKing spitzer boat-tail or Nosler 165-grain spitzer Partition. It will send either bullet down range with a velocity of 3,110 to 3,120 fps from the 26-inch factory barrel. Typical five-shot groups with either bullet fall between the perimeters of .750 and .875 inch off the bench at 100 yards, when I do my part.

The bulk of the 165-grain bullets that go downrange are the Sierras, with the intended targets being paper or steel, with the odd jackrabbit and coyote thrown in for some real-world practice. The Nosler Partitions are reserved for hunting the likes of whitetail and mule deer, elk, moose and African plains game – and what a fine job they do. Of all big-game hunting caliber rifles I own, this rifle and cartridge combination is my go-to rig for most of my hunting.

One note of caution: one reloading data source back in 1970 listed a maximum load of 70 grains of IMR-4350 and a 165-grain bullet. This is way too hot for my Model 70 or its stablemate, a Sako M85 prototype commissioned for a special project during my tenure as manager of technical services with Beretta USA. Most data sources of today show a maximum charge of 67 to 68 grains with a 165-grain bullet. This just reinforces the longstanding axiom that loading data is definitive only for the actual make and type of bullet used to develop the data and the test barrel it is fired from. Fired from any other rifle barrel – with a bullet of a different profile or construction – and all bets are off. Always start with a reduced or minimum listed load when developing loads for a specific rifle and bullet.

Over the years IMR powders have made the transition of ownership from DuPont to IMR Powder and more recently to Hodgdon Powders, which rebranded the product line as IMR Legendary Powders. The IMR series of powders continue to be manufactured at the powder works located in Valleyfield, Quebec, Canada, where they have been made since the early years of World War II.

Interestingly, many shooting publications incorrectly reference the Valleyfield plant as being situated in the Canadian province of Ontario.

In a recent conversation with Ron Rieber of Hodgdon Powders, he mentioned the fact that whether it be IMR-4350 or its close cousin, H-4350, Hodgdon’s annual production quantities never meet the ongoing demand for these two exceptionally broad-spectrum propellants.

A classic is defined as “an outstanding example of its kind, something of lasting worth.” I think it is fair to say that IMR-4350 is an outstanding example of a propellant that, over the last 80 years, has and continues to prove its worth. It’s truly one of the classic propellant powders of all-time.

.jpg)