Reloader's Press

Elite Sixguns Have Fixed Sights

column By: Dave Scovill | December, 20

I pulled the Colt out of the holster and answered in the affirmative, that at one time the Colt and a Hawes Western Marshall were the only sixguns I had that were suitable for hunting. He was fixated on the Colt, and in so many words stated that he was sure I was aware that there were better handguns with good triggers and adjustable sights that were more accurate for serious work like hunting.

It wasn’t the first time someone questioned my judgment regarding that old Colt, but it was the first occasion to be dressed down over it. Under the circumstances, I let the gentleman chew on me a bit, but after a couple of cervezas, I asked if he had done any serious work with a Colt SAA, or any of the S&W duty revolvers with fixed sights. He had not, mostly because he required target sights for good accuracy, and his readers expected him to use an elite handgun that was capable of fine accuracy. It was the first time I had heard anyone refer to a Smith & Wesson as “elite,” as if the rest of the industry were building second-class trash, or worse.

As for the difference in quality in sights, such as fixed sights on a Colt, Smith & Wesson or Ruger, in my opinion it’s simply a matter of familiarization with the sights, and practice* shooting at targets placed at various distances other than 25 yards. That adds up to field experience with opportunities to shoot at unknown ranges, including thousands of shots at small game – jackrabbits, badgers, foxes, coyotes and prairie dogs – or deer, even rocks or whatever over the years.

It is also important to know that adjustable sights are not necessarily target sights or vice versa. Moreover, target sights do not necessarily make good hunting sights, although a good set of adjustable sights might prove quite adequate for field use.

The problem with target or adjustable sights is the fine line between being able to see the front sight clearly in the rear notch. Some guns have front sights that nearly fill the rear notch, making it difficult to acquire the proper sight picture quickly and accurately. Those sights are good for a fine-tuned sight picture on targets but are simply too slow for field work.

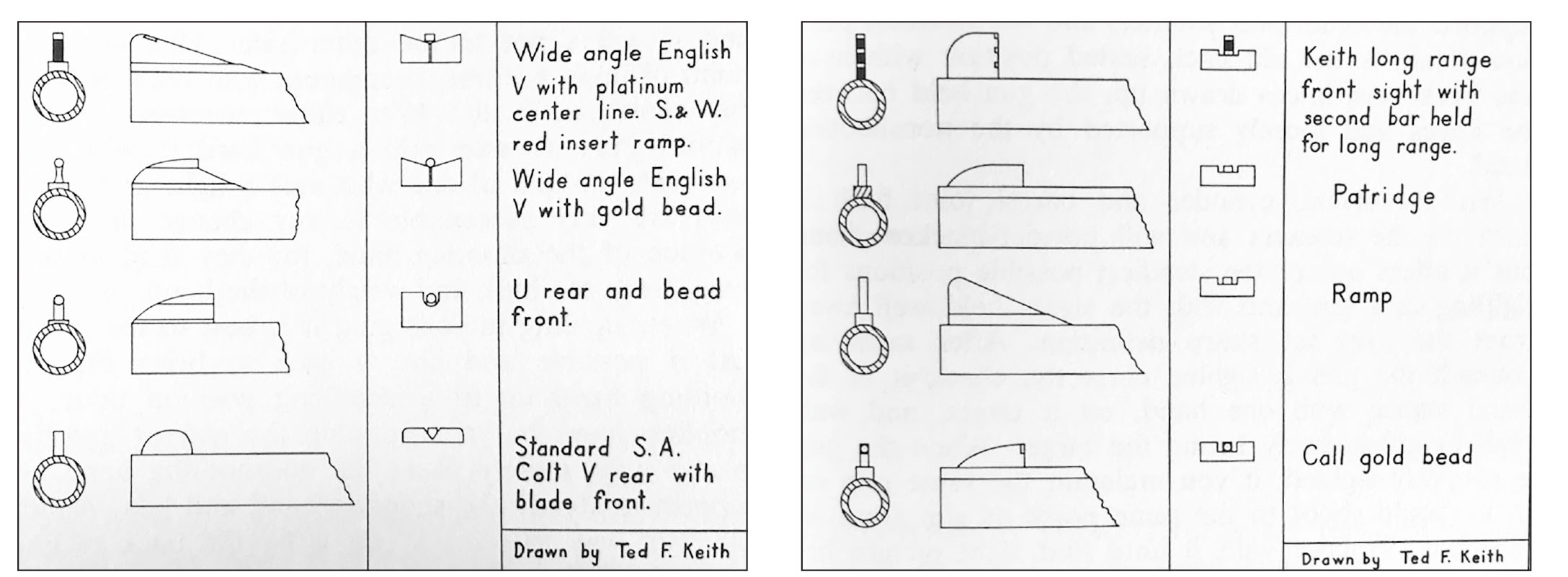

A Smith & Wesson Second Model Ejector Target .44 Special I used for many years had a Call gold bead inlaid in the top rear of the Patridge-type front sight that, when aligned in the rear notch at arm’s length, appeared as wide as the rear notch, making it nearly impossible to align the front and rear sight quickly. With lots of time to take each shot on paper targets with a six o’clock hold at the bottom of a black bull, it was quite accurate with good loads. In the field, however, it required too much time to align the sights before the target, which in most instances was long gone.

The saving grace with those sights was on long shots, 50 to 100 yards, out where the rear sight was lowered a bit (estimated) to elevate the barrel and accommodate for the range, albeit the sides of the front sight below the top of the rear notch left a very thin line of light to outline the front sight in silhouette on either side. The upper portion, however, with all or part of the round, gold bead centered over the rear notch – like a large ivory bead on a big double rifle is centered over a rear notch – is quick to acquire and is entirely sufficient for field use.

A shallow V cut in the rear of the top strap are the most difficult to use, owing the small area to align with the front sight blade or bead. These sights require great precision to align, much like some target sights that consist of a shallow U rear notch that is intended to accommodate a round, sometimes gold or ivory bead, up front.

The latter setup describes closely the sights on the early Colt New Service Target .44 Russian that set the world record perfect score in 1906. In use, the New Service Target sights are intended to be set up (adjusted) for the load of interest and not changed. So they are adjustable to a point, but not readily changed in use. In effect, the shallow V and U rear notch can be the most difficult to use, but for good eyes and a steady hold, produced fine accuracy.

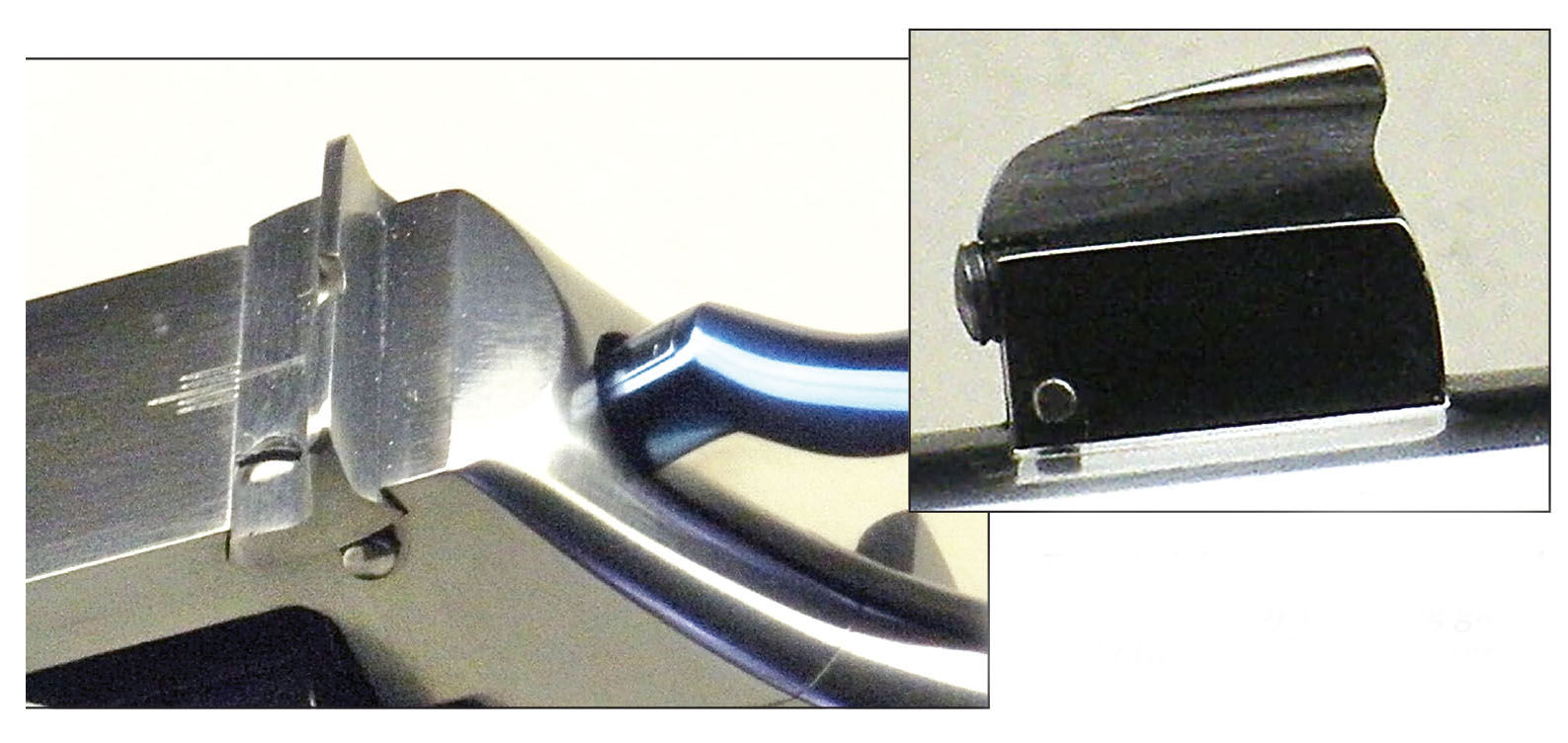

The most famous of the long-range Colt SAA revolvers had fixed sights with stadia lines engraved across the rear face of the front sight blade to use as references to align with the top (or bottom) of the rear sight notch. Each line was used as a reference for a given distance. In the field, where the exact range may not be known, the best guess, based on years of experience in the field, might not coincide with any of the stadia lines but may equate to the space between the 100- and 150-yard reference lines. The shooter splits the difference and aligns the top (shooter’s choice, top or bottom) of the rear notch with the guesstimate between 100 and 150 yards. This fairly describes Elmer Keith’s Long Range Colt, which when in actual use was quicker and possibly more accurate than attempting to adjust so-called target sights in the field with a screwdriver.

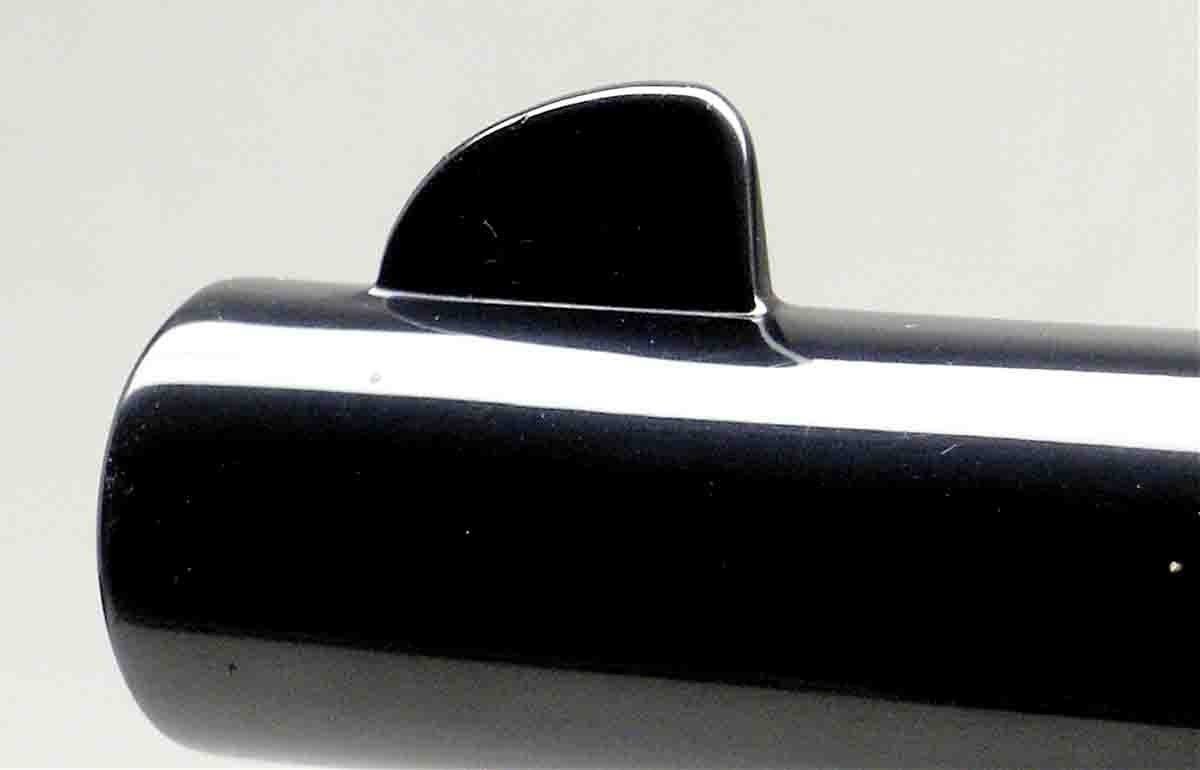

Short of having two or three stadia lines for reference, I have used what is commonly referred to as a Sourdough front sight for roughly 30 years. The Sourdough is usually associated with rifles, but the concept works with handguns as well. In use, the Sourdough has a blade (standard) up front that has the top rear corner cut at roughly a 45-degree angle. The flat surface angle serves two purposes: 1) to reflect light toward the eye, which can be left in the white or finished with fluorescent paint, and 2) the line formed by the lower edge of the flat angle serves as a second reference line that when in shooting position at arm’s length is held in line with the top (or the bottom) of the rear notch. On my sixguns, the lower line formed by the angled surface held in the top of the rear notch is intended to act as a stadia line for an approximate 100-yard zero with typical hunting loads in .44 and .45 Colt SAAs or their copies out of Europe.

Obviously, the Sourdough front sight requires quite a bit of cut-n’-try with a file and a steady hand with the preferred field load, albeit it can be used in standard fashion with the top of the front sight lined up with the top of the rear notch for practice at point-blank range, 25 yards or so, and extended field (hunting) ranges.

One of the advantages served by the Sourdough front sight on rifles and handguns is to reduce or eliminate glare from the heretofore rounded rear edge of the front sight. The second advantage is to offer an additional reference point for aiming beyond point-blank target ranges.

For “elite” shooters, as my associate referred to them, my shoot-n’-try method of using fixed sights with older Colts or their copies out of Europe has been criticized from time to time by readers and former staff writers who choose to shoot more refined revolvers with adjustable sights, which are no more “target” sights than all scopes would be “target” scopes. When these folks do shoot fixed, sometimes referred to as rudimentary, sighted revolvers, they sometimes move the target in to 15 yards, the standard range for cowboy-type shooting.

All of the above assumes you are shooting with both eyes open and focus on the front sight. The urge, apparently, with inexperienced handgun or rifle shooters is to close one eye and to raise the front sight for longer shots, but that causes the front sight to cover the intended target, which only exacerbates the problem. Always lower the rear sight in relation to the target and place the top of the front sight at six o’clock, directly below the intended point of bullet impact.

*With both eyes open and using a standard sight picture for 25 yards, but firing at a paper target out to 75 or 90 yards, note where the bullet hits and lower the rear sight to that point for the second shot with the front sight at six o’clock as before. This elevates the barrel at a slight angle and accounts for the bullet drop, estimated or known, at longer ranges. This effectively explains how Elmer Keith, with the aid of stadia lines, was able to walk his shots into a deer-sized target at 600 yards. For the final shot, Keith stated he held all of the front sight up in the rear notch and visually placed the top of the front sight on the deer.