Shooting the Renowned G33/40

Or Trying To

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 23

The Vz33 was a Mauser 98 with certain modifications and was the Czech army’s main service weapon. It also served as the basis for some specialty rifles of different barrel lengths. In 1940, the Wehrmacht adopted one of these as the basis for a light, short-barreled rifle for use by mountain troops. It was designated the G33/40 – ‘G’ for Gewehr, or ‘rifle’ and ‘33’ for the Czech connection, along with ‘40’ for the year of adoption.

It was reputed to weigh, unloaded, 7.6 pounds. Mine, unloaded but with a sling, weighs 8.3 pounds, compared to 9.25 pounds for a K98.

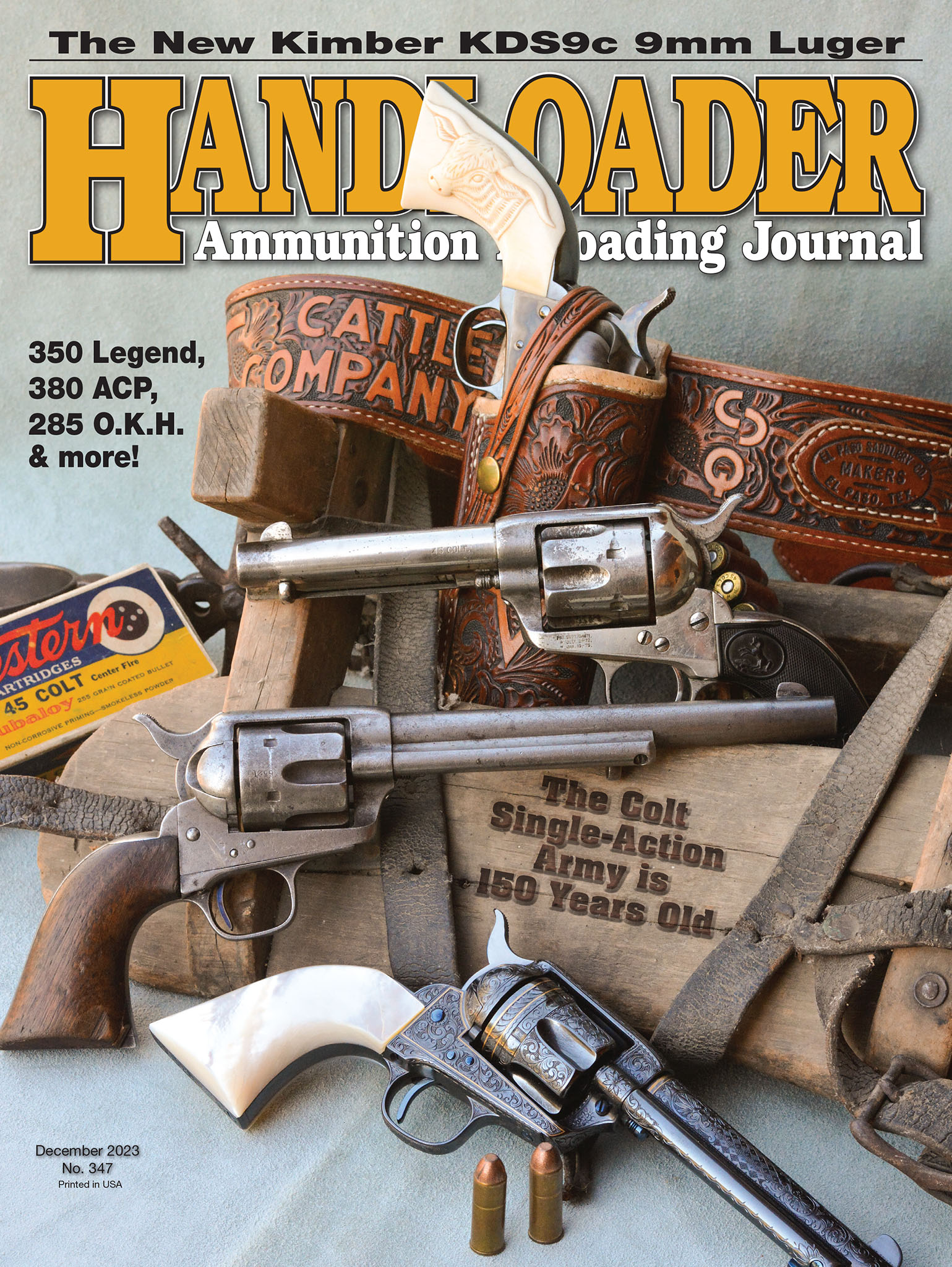

The G33/40’s virtues as a lightweight military rifle, combined with the superb quality, made it desirable both to military collectors and to gunsmiths wanting to use its action as the basis for a light, mountain-hunting rifle.

It has been estimated that about 120,000 G33/40s were produced from 1940 to 1942, and only a fraction of those survive today in their original condition. Between the attrition of warfare, destruction of surplus stocks, and cannibalization by gunsmiths, the G33/40, especially one in fine condition, has become a rarity and prices have soared. Today, one in collectible condition will command $3,500 to $4,000.

In 1965, as a 16-year-old in love with rifles and hunting, I was offered the chance to buy a G33/40 in what looked to my eye, then, as virtually new condition. I’d already agreed to the purchase of a sporterized Enfield P-17, but when I went to pick it up, I was given the option of the G33/40, which my friend Dick, the seller and a serious gun collector, said was, overall, a better rifle. Alas, in the interim I had researched the P-17 and fallen in love with the 30-06, so I passed it up. The price was $30 for either one. That seems like nothing, now, but to a teenager in 1965, it was a serious investment.

That brief introduction, however, kindled a desire for a G33/40 that lasted 60 years, and when one came along a few years ago, I grabbed it. As the photographs show, it is in about as fine a shape as one could hope in a rifle of its age and background, and yes, I paid the collector value for it. Short of a miracle or a deranged seller, you’re not going to find one for less.

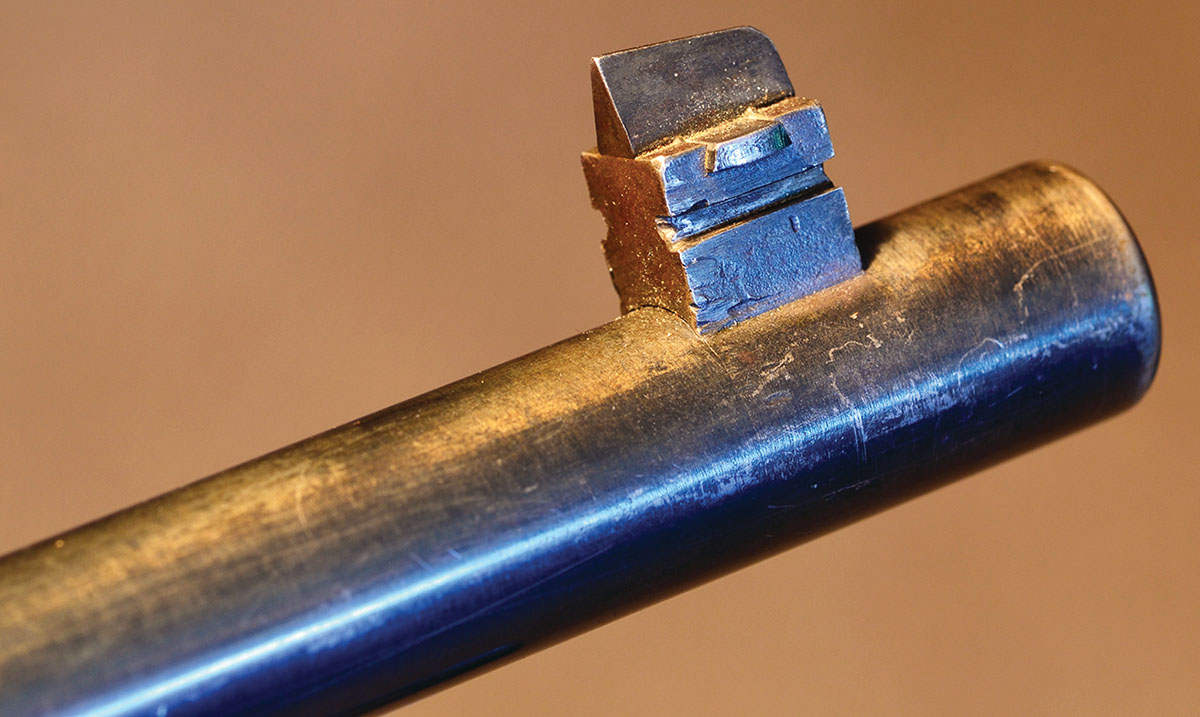

Naturally, the minute I laid hands on it, I took it to the range and there I found that, inexplicably, it put all its bullets at least a foot high at 100 yards, with the rear sight set all the way down at 100 meters, its lowest setting. The only solution in terms of sights would be to replace the blade front sight with a higher one, which I refuse to do.

However, I still wanted to shoot the rifle. That is, after all, what it was made to do, and I wanted to see what it could and could not do.

The ammunition I used was handloads that had worked well in other 8x57 JS rifles, including a civilian Mannlicher. Bullet weights ranged from 150 to 200 grains, with velocities from 2,350 feet per second (fps) to 2,750. Although they all grouped fairly well (4- to 5-inch, five-shot groups at 100 yards), they all printed 12 to 15 inches above the point of aim. This was using the original military sight, which is a simple ‘V’ with a barleycorn (inverted ‘V’) front sight, at its lowest setting of 100 meters.

It would seem very odd to me that a battle sight would be set for a long range anyway, since most enemy encounters where you would need it would be within 100 yards.

The obvious first problem is determining exactly what ammunition the rifle was originally regulated for and that is an impossible task. The only thing most of the sources agree on is that there was a wide range of ammunition used by the Wehrmacht, none of which is available today through standard channels, and even if it were, you would probably not shoot it.

Since I am certainly not going to alter any feature of the all-original G33/40, this leaves a process of trial and error, hoping to find a load that works.

The bullets I had available that might work were a Speer 170 grain, Hornady 195-grain spitzer, Hawk 200-grain roundnose and a cast 210-grain bullet. Ostensibly, the original military load for this rifle was around 196 grains.

My reasoning was that recoil from a faster bullet would cause greater muzzle jump and a higher point of impact. Therefore, reducing the recoil by lowering the velocity, and/or the bullet weight, could counteract that. Lower velocity would also result in greater bullet drop over 100 yards. Would that suffice? Only one way to find out.

I put together four loads, using four different bullets from four different makers, and four different powders. Powders were chosen on the basis of burn rate, going with faster ones because of the rifle’s short barrel. The combinations were minimum starting loads.

Because of the 8x57 JS’s checkered history, beginning with one bullet diameter (.318 inch) then switching to another (.323 inch), then widen number of countries that used it, and an endless assortment of rifles chambered for it, ranging in quality from superb to (probably) perilous, the compilers of loading manuals tend to be ultra-careful in their recommendations. Not surprisingly, one finds a wide range of loads.

The Hornady 195-grain was the closest I could come in bullet weight and configuration to the original German military load with which the G33/40 was presumably regulated, but both it and the Hawk 200-grain load scattered bullets. Attempts to work up and stabilize them at slightly higher velocities went nowhere.

The cast bullet load was, in a nutshell, a waste of time, powder and lead.

As you can see, the Speer 170-grain bullet has neither a crimping groove nor a cannelure, so I could not crimp the bullets. Loading rounds into the magazine three at a time, I found that after two shots, the bullet of the third round had jammed completely back into the case. This problem would only get worse if I increased the powder charge. I could get a tool and press a cannelure into the bullets, but even for me, that might be going a bit far. Instead, I will try to locate some bullets of the same weight with a cannelure and try those.

Unfortunately, after the shortages of recent years, manufacturers have not rushed to replenish their stocks of 8mm (.323 inch) bullets, and as I write this, pickings are slim.

But, as I said at the beginning, the objective was simple and direct, and I now have one load that will work, and hit that 8-inch plate out to 100 yards. Most of the time, anyway.

.jpg)