British No. 1 MK III & Pattern 1914

Battle Rifles in Transition

feature By: Mike Venturino | April, 18

Now here is a caveat: The evolution of SMLE design is contradictory, according to various sources. In Military Rifles of Two World Wars by John Walter, the author gives 1916 as the date of transition from SMLE Mk II to SMLE Mk III. In Military Small Arms of the 20th Century, 7th

Despite the different models, the one feature most notable at a glance was the change from a round cocking piece at the bolt’s rear to a flat one. Military rifles in general are not considered pleasing to the eye, but the SMLE has to be one of the most homely military rifles to come along before synthetics. Its 25-inch barrel is covered by wood nearly to the muzzle, where a heavy steel nose piece takes over. The nose piece has a protruding stud for mounting a bayonet, and “ears” atop it to protect the front sight. The upper portion of the barrel is likewise covered by a wood handguard from the front receiver ring to the nose piece. In between the receiver and muzzle are a heavy steel barrel band/sling swivels and open rear sights.

Buttstocks on Mk IIIs look odd to Americans. There is no actual pistol grip, but they are not of straight-grip design either. Actually, the stock has a “hand recess” with a bump at the rear to hold the shooter’s hand approximately in the same position. Another deviation for contemporary military rifles was that Mk III stocks were made of two pieces joined by a collar at the rear of the receiver. That feature was not for economy of stock wood. Buttstocks came in three lengths so Mk IIIs could be approximately fitted to individual soldiers. SMLE buttplates were made of steel or brass.

The long-range, open rear sights originally used on SMLEs were a wonder of engineering, especially considering that open sights are the least precise of all rifle sighting equipment. They

One thing that can be said about nineteenth-century British politicians is that they have no qualms about declaring war on other nations while being woefully unprepared in terms of weaponry. By 1913 British Ordnance officers realized their SMLE and .303 cartridge were out of date. The much stronger front bolt locking system of Mauser rifles was attractive if they were also going to transition to a higher pressure cartridge as was being used by German and American armies. It was thought one of .276 caliber would be even better than the German’s 7.92mm or the American’s .30-06.

American military rifle manufacturers traditionally stamped their names on their rifle

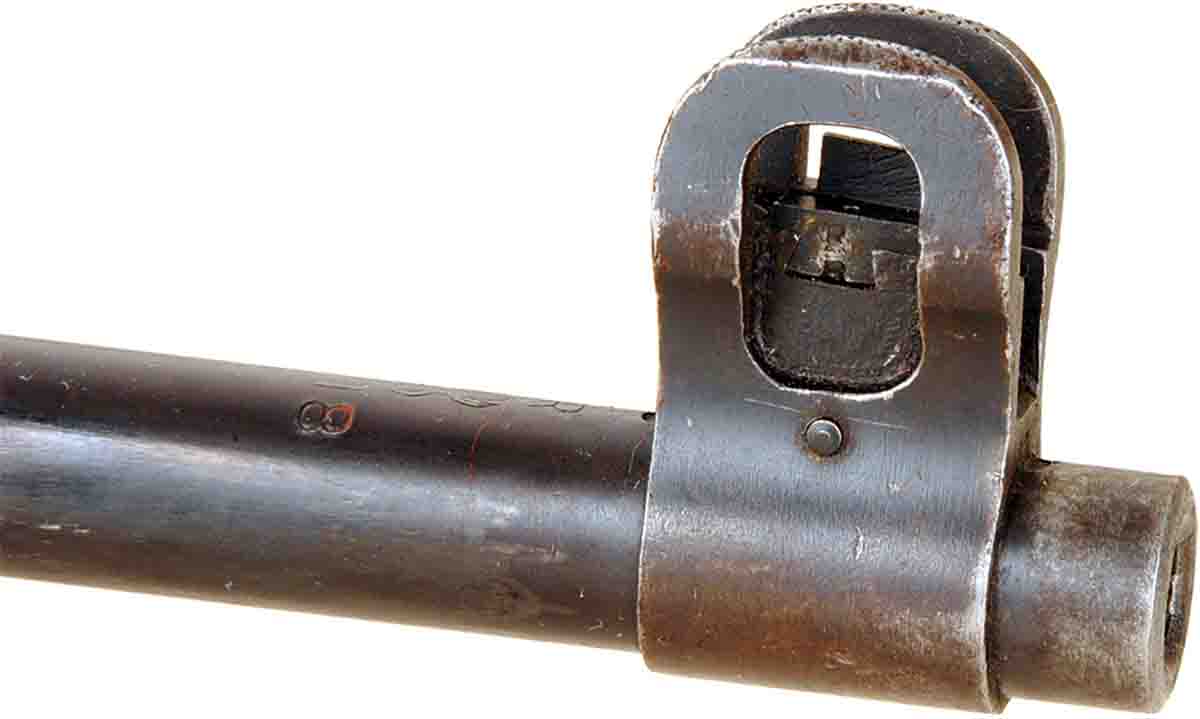

About the only thing similar to SMLE Mk IIIs was the shape of Pattern 1914 buttstocks. Keeping with the British insistence on fast bolt manipulation, P14s had a dogleg-shaped bolt handle. The rear sight contained two apertures of .010-inch diameter. One was the standard battle sight with the rifle zeroed for 300 yards. The other sight came into play when its ladder section was raised. The second aperture was then visible and could be elevated to 1,650 yards. A very distinctive feature of Pattern

British designers put some thought into protecting the sight by adding sturdy steel “wings,” a good idea in an era when bayonet fighting was considered important. Also, wings on front sights have portals so sight blades can be moved laterally for windage zeroing. There is no windage adjustment in the rear sights.

Another wasted sight effort of Pattern 1914 designers were volley sights along the rifle’s left side – a peep rear and post front. These again were for volley fire at extreme distances, and were so useless in practice that they were ordered removed from the rifles at their reissue at the beginning of World War II.

I now would like to take a moment to editorialize about SMLE and Pattern 1914 sights. In Military Small Arms of the 20th Century, 7th Edition, the authors state that the SMLE’s finely adjustable rear sight was the best ever put on a military rifle. As a rifleman for most of my adult life, but admittedly not with military experience, I have to disagree. SMLE long-range sights are nice pieces of craftsmanship, but open sights are in no way advantageous over aperture sights. In my humble estimation, Pattern 1914 rear sights are far more practical. Consider this: American military rifles starting with the Model 1917 (a minor redesign of the Pattern 1914) featured aperture sights. M1 Garands, M1 Carbines, Model 1903A3s, M14s and M16s all carried aperture sighting equipment. And unlike the sight on Model 1903 Springfields, all those rifles have sights located where they should be – near the shooter’s eye.

There is contradictory writing concerning the British use of Pattern 1914s in World War I. In more than one publication it has

Back in the 1960s as a teenager, in every gun store encountered I perused their used rifle racks. There were almost always British .303s, and some even had sturdy wire wrapping around stocks. In my inexperienced mind I thought, What kind of country has to wire their rifles together? Much later I learned that the wire was meant to sturdy up stocks when a specific rifle was used for launching grenades.

As noted, the British system of military weapon nomenclature gets very confusing. The SMLE was named No. 1 Mk I, II and III, with minor variations gaining an asterisk to denote some change. Somewhere there must have been a No. 2, but I cannot find one. After World War I the Pattern 1914 was given a No. 3 designation, and then in 1942 the basic version of the SMLE underwent a remodeling and was renamed the No. 4. It also gained a bunch of Marks and asterisks. The famous “Jungle Carbine” introduced late in World War II became the No. 5; at least I think all that is correct. All were made in Britain, India and Australia.

I never personally envisioned an SMLE of any Mark in my life until beginning work on my book Shooting World War II Small Arms. Then research revealed that SMLEs were vital to Britain early on and also were much used by Australian and New Zealand troops in Africa and Pacific Theaters. Eventually I purchased an SMLE Mk III made at the Lithgow facility in Australia. My prejudices were not so strong against Pattern 1914s, and one of those by Winchester had already gained a place in my rifle racks years before the book idea took hold.

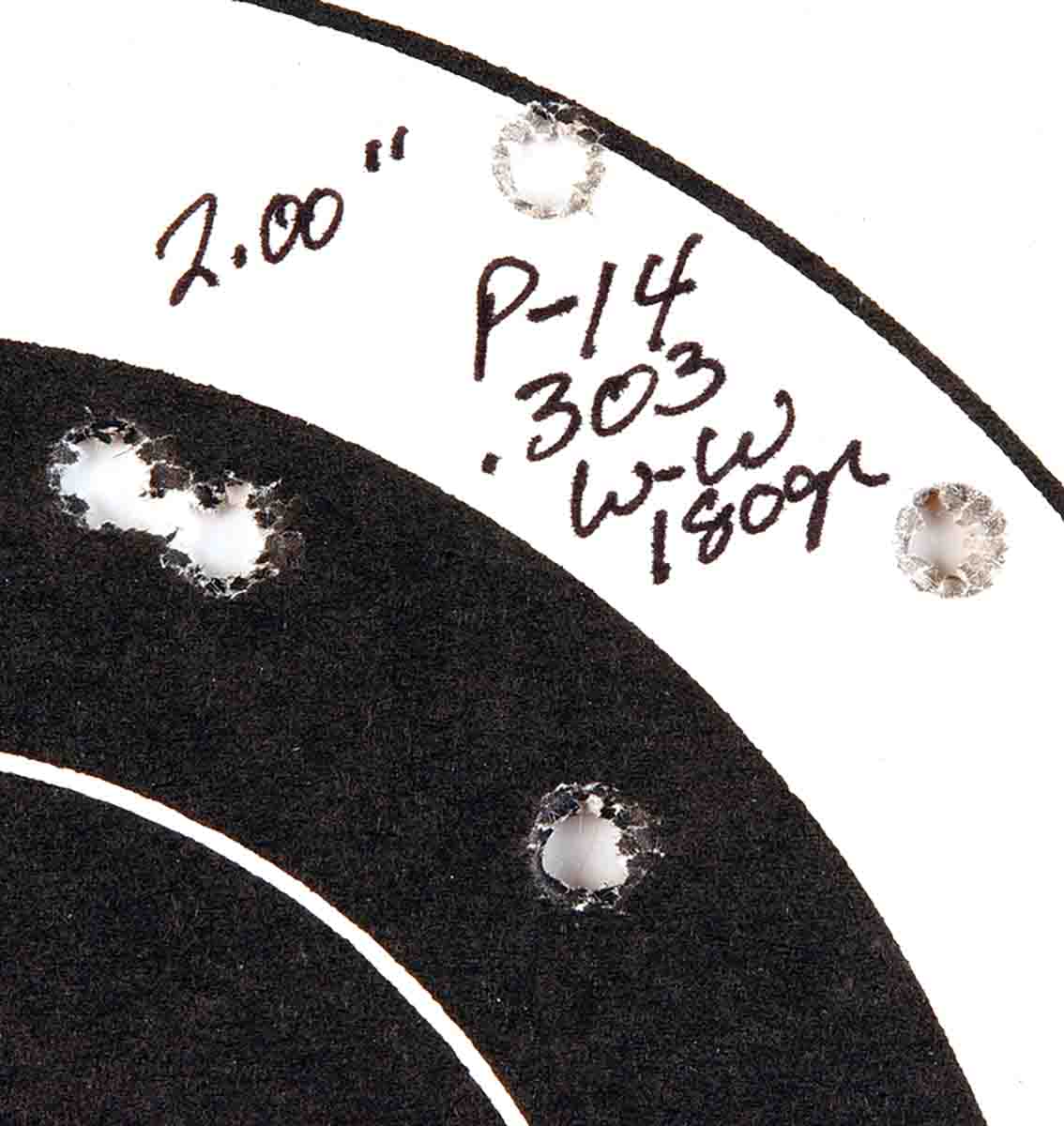

My attitude is reversed with the Pattern 1914. It is capable of better accuracy, has a better sight system and is no harder on brass than any rifle with front bolt locking lugs. So when the urge strikes me to shoot some .303 ammunition, it’s my pick of the half-dozen or so rifles and carbines so chambered.