Bullets & Brass

Can Powder Reaction Split .44 Magnum Cases

column By: Brian Pearce | April, 18

Q: First, I would like to say that I have subscribed to Handloader for more years than I care to remember. I consider it a best-of-class publication and look forward to reading it every month.

On a recent trip to the range I decided to shoot up a stock of .44 Magnum handloads that have been in storage for many years. My handloads are stored in plastic boxes indoors and away from temperature extremes and moisture. All rounds fired, and I had no problem hitting steel plates at 100 yards. I noticed, however, that there was an unusual amount of powder residue on the outside of the cases, far more than would be expected for a full-power .44 Magnum load. Further inspection showed that about half of the cases were cracked. I then inspected some of the unfired cartridges and noticed that a few had a turquoise-colored corrosion on the case at the same point where the cracks were observed.

Upon returning home I pulled the bullets on the remaining loads and inspected the cases. The insides of the cases and the bottom of the jacketed bullets were all covered in a green patina. Moreover, the powder had clearly gone bad. It exhibited brownish rust and contained some yellow and off-colored kernels.

The powder in question was Vihtavuori N110, which is my go-to powder for .44 Magnum loads. There is no question that the powder reacted with the brass and copper jacketed bullets.

There are some unusual chemical compound ingredients in Vihtavuori N110 as they list diphenylamine (3.0%), diethyldiphenylurea (6.0%), potassium hydrogentartrate (2.0%), and potassium sulphate (2.0%). Is it possible that one of these compounds was the cause of the brass reaction? An opened can of N110 of the same vintage as the reloads in question did not show any obvious deterioration, so I am guessing that the presence of copper had something to do with the problem. Have you ever heard of this phenomenon? Thanks again for a great magazine! – H.G., via e-mail

A: It would have been helpful to have known more details about your loads, including the date that the powder was manufactured, how many times your cases were reloaded, their make, the climate where you reside, etc. But your problem probably boils down to powder deterioration, which can cause erosion to cases and copper-jacketed bullets.

As you know, brass is constructed of a blend of copper and zinc; however, sometimes there are small percentages of lead, phosphorus, aluminum, magnesium, silicon, arsenic and other materials, which are generally intentionally included. Incidentally, the majority of brass used in the U.S. is from recycled material. However, most case manufacturers try to keep their brass content as close to pure as possible. These materials generally do not interact negatively with the ingredients used in smokeless powders. However, it has happened many times in history. For example, the British Army had problems with cases delaminating during the 1920s when ammunition was stored in barns that had traces of ammonia in the air. I have seen surplus ammunition from around the world that showed signs of rust, corrosion and break down. However, their origins and storage conditions were largely unknown. A large European ammunition company recently had new cases delaminate after being loaded and shipped to the military, and was traced to excessive amounts of zinc in the case construction that was originally intended to harden the brass to reduce case head expansion with high-pressure loads.

Again, I believe that your problem can be traced to the powder, which had deteriorated and caused the reaction with the brass case and copper bullet. Vihtavuori is a member of the Commission Internationale Permanente (C.I.P.), essentially the European counterpart of the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI). It specifies that powders have a shelf life of 10 years from the date of manufacture. From the description that you offer, I am left with the impression that your .44 Remington Magnum handloads and age of the powder probably exceeded 10 years. Incidentally, SAAMI has no limitations for the shelf life of powder.

In discussing your experience with Vihtavuori, the company is currently using new powder washing methods that will help extend powder shelf life. It is also working on formulas to make its powders less temperature sensitive, more tolerant of being stored in a variety of temperatures and humidity levels, and help control barrel copper fouling.

Virtually every propellant manufacturer suggests regular rotation of powder and ammunition. Your experience is a good reminder to all of us that components should be kept as fresh as possible.

Ruger New Model Blackhawk Pressure Limits

Q: I have been a subscriber to Handloader for many years and appreciate all of the fine articles. I recently purchased a Lipsey’s Ruger New Model Blackhawk stainless steel chambered in .45 Colt with extra cylinder in .45 ACP. I have handloaded for many years and was wondering what pressure level I should not exceed. I believe that you have covered this very subject before, but cannot seem to locate your article in past issues. – G.L., via e-mail

A: I have not conducted scientific destruction tests (but I have done so with other guns) to determine stress and breaking points of the Ruger New Model Blackhawk .45 Colt, built on the “.357 fiftieth-anniversary frame,” nor am I aware of any labs that have. However, in measuring outside cylinder dimensions, chamber wall thickness, the amount of steel between chambers, the steel thickness over the cylinder latch notch (bolt stop notch), along with the steel type and quality, they clearly can handle loads that generate up to 23,000 psi.

Ruger only recommends using .45 Colt factory loads that are within SAAMI pressure guidelines established at 14,000 psi, which is clearly an effort to reduce liability. However, when you “convert” your revolver to .45 ACP by changing cylinders, Ruger recommends that cylinder with +P .45 ACP loads, with industry maximum average pressure being established at 23,000 psi. Incidentally, the .45 ACP cylinder shares very similar dimensions and strength as the .45 Colt cylinder, but is not identical.

When the .45 Colt is loaded to 23,000 psi, it will give notable power, as I have taken a number of deer and black bear cleanly. For what it may be worth, my sons and I have shot thousands of .45 Colt rounds loaded to this pressure level through several New Model Blackhawks built on the smaller .357 fiftieth-anniversary frame without problems. I hope this information helps.

.45 ACP Cartridge Pressure

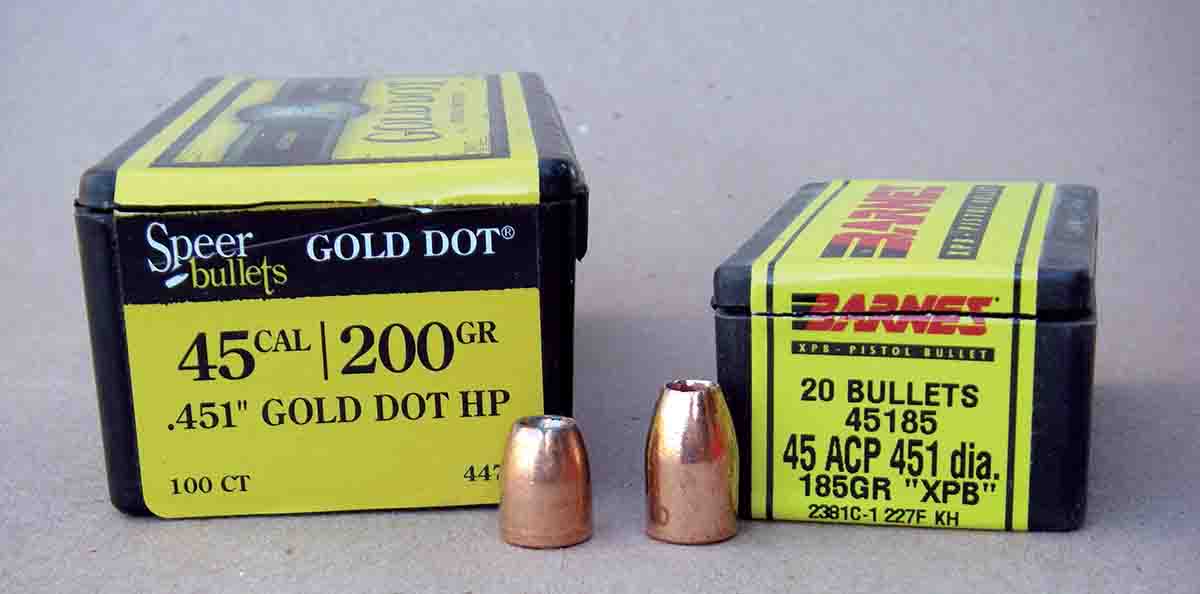

Q: Regarding your article, “Pet Loads, Loading the .45 ACP” in the October 2017 issue of Handloader No. 310; I have a quick question. You list the Barnes 185-grain XPB bullet with 7.0 grains of Alliant Unique powder for 1,062 fps. Then the Speer 200-grain Gold Dot HP is loaded with 7.3 grains of the same powder and generates 1,105 fps and no +P designation. What gives? – M.B., via e-mail

A: You raise an excellent question. The Barnes 185-grain XPB bullet is effectively constructed of pure copper (actually 99.5 percent). This results in a comparatively long bullet that seats more deeply into the case than any lead core jacketed bullet of the same weight, as well as all conventionally designed 200-grain, cup-and-core bullets. This reduction in precious powder capacity (in the already very short powder column of the .45 ACP) severely limits what powders can be used with that bullet, as well as powder charge weights. Many powders are excessively compressed, or simply cannot be used as there is not enough case capacity for powders that tend to be bulkier.

In spite of being tapered in an effort to reduce bore friction and chamber pressures, the Barnes bullet will raise pressures when compared to a cup-and-core bullet of the same weight. All of this explains why the 185-grain XPB received a lighter powder charge and is +P rated, whereas the Speer 200-grain Gold Dot HP bullet could be loaded with a heavier powder charge and resultant lower pressures.

I hope the above insight helps to answer your question, and thanks for taking the time to read our magazine.

.44 Special Loads

Q: I am a longtime reader and huge fan of your work. I really enjoyed your recent article about your grandfather and the Model 1895 Winchester rifle.

I would like to ask you for guidance on a .44 Special load for my Smith & Wesson Model 629-5 and my sister-in-law’s Smith & Wesson Model 21-4. I have a quantity of .430-inch, 190-grain lead SWC-HP bullets as offered by GT Bullets (www.gtbullets.com) that I would like to push to around 1,050 fps to 1,100 fps. I would like to replicate the Buffalo Bore or Underwood loads using the same bullet weights. This load would also be used in a Marlin Model 1894 as a “house load.”

I have about 200 pieces of virgin Starline brass that is sized, primed with Winchester Large Pistol primers, case mouths expanded and ready to load. The pistol powders that I have at my disposal include Alliant Unique, Power Pistol, Hodgdon Titegroup, Universal and Lil’ Gun. Thanks for your assistance. – G.T., USMC, Murrieta, CA

A: The .44 Special Buffalo Bore load that you mention contains a 190-grain soft hollowpoint bullet with gas check at an advertised 1,150 fps. The 190-grain lead SWC hollowpoint bullet from GT Bullets that you are using is slightly different, but you should be able to reach the same velocities without difficultly. However, you will need to watch for barrel leading.

From a Smith & Wesson Model 1950 Target Model 24-3 with a 4-inch barrel, 10.0 grains of Alliant Power Pistol powder ignited with a CCI 300 primer reached 1,086 fps, which is within the velocity range you requested. From a Marlin Model 1894CB (with Ballard rifling), velocity was 1,403 fps. You should be able to use your Winchester Large Pistol primers interchangeably with this particular load.

If you want to truly duplicate the Buffalo Bore load in your revolvers, try 10.6 grains of the same powder for around 1,150 fps. Thanks for the fine compliments, and I am glad that you enjoy our magazines.