Cartridge Board

.375 Flanged Nitro Express (2 1/2)

column By: Gil Sengel | December, 17

Anyone who studies shooting history knows that many companies acquire a reputation for producing a particular type of firearm. In the U.S., for example, lever-action rifles will probably be forever associated with Winchester. Now consider Great Britain and its famed double rifle. Here again, one name stands out, Holland & Holland (H&H), even though several makers produced superb examples of such rifles.

This standing developed from H&H’s experimentation with rifling twists and forms beginning in the 1860s. Knowledge gained was put into the companies single-shot rook and rabbit rifles that were extremely popular in the 1870-1890 time frame. So successful was this work that by the late 1880s, H&H was considered the premier sporting riflemaker in Great Britain.

Holland’s experimenting with rifles did not stop at barrelmaking. The advent of smokeless powder quickly illustrated the need for new cartridges. However, H&H did not immediately jump into the new cartridge designing fray, instead waiting a bit to learn more about nitro powders.

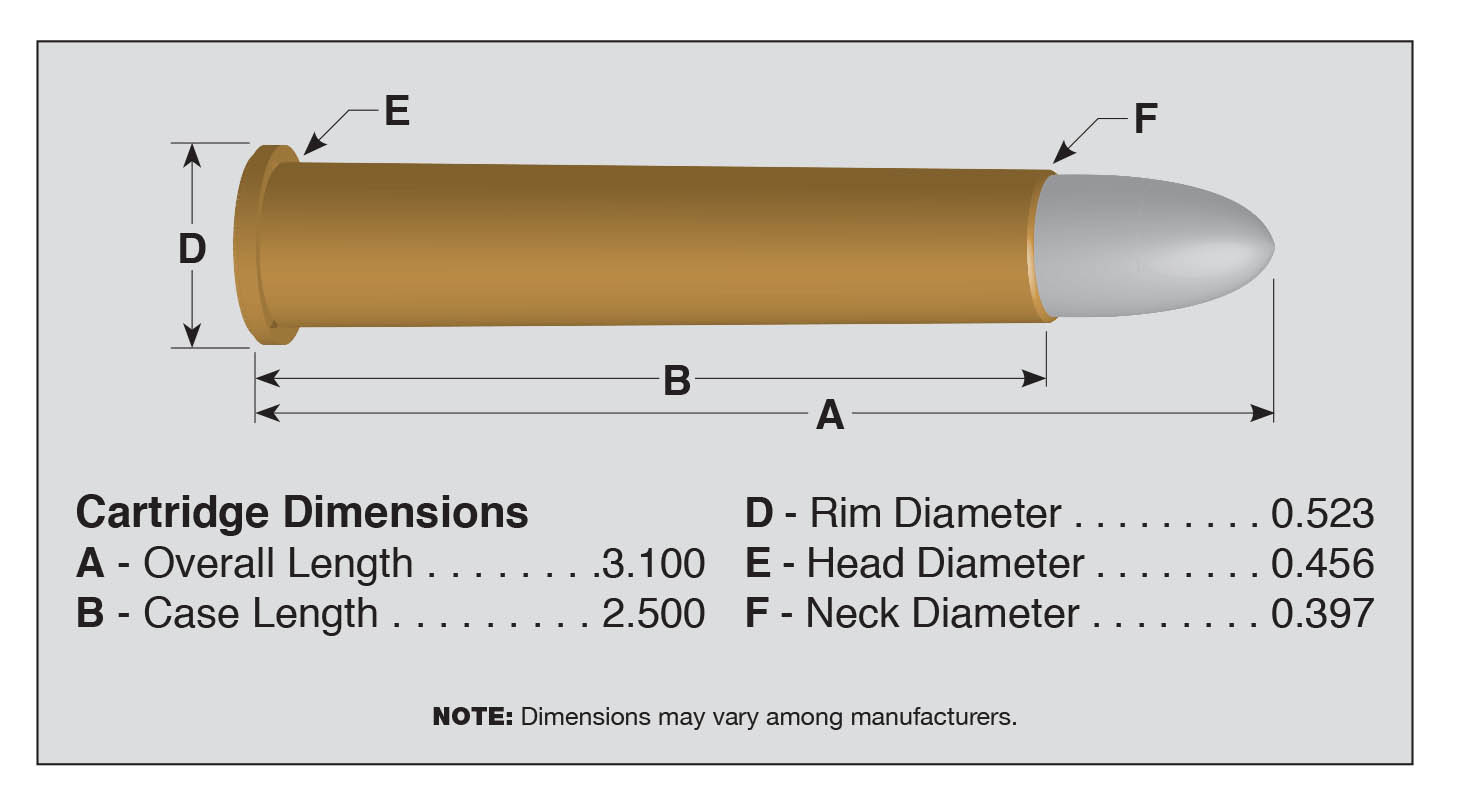

The year 1899 saw H&H bring out its first smokeless hunting round using a slightly lengthened .303 British case. It was originally called the .375 Cordite Express, or .375 Flanged Nitro Express, then later it became the .375 Flanged Nitro Express (21⁄2) to differentiate it from newer .375 rounds.

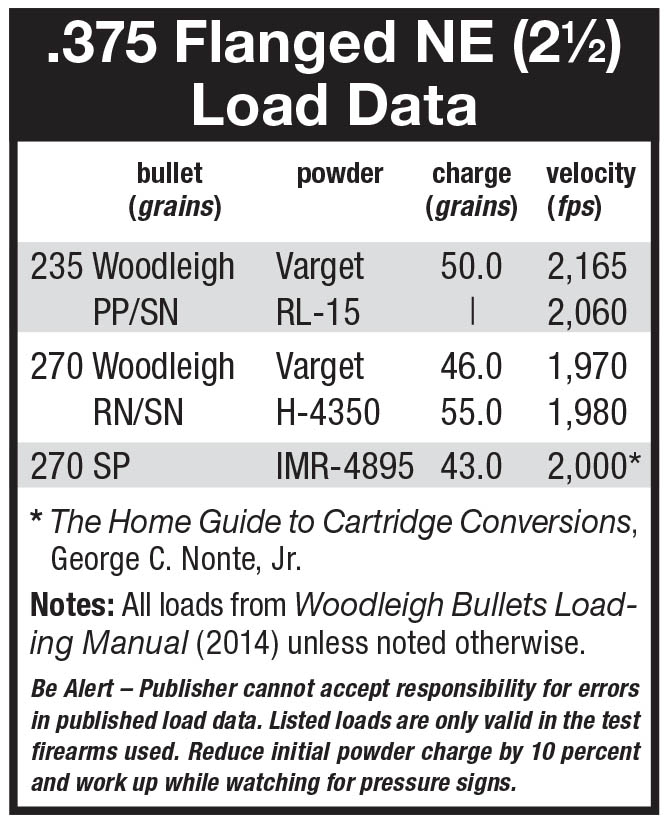

Ballistics show a 270-grain softpoint, solid and Holland Patent Peg Bullet, a large-cavity hollowpoint with a tapered insert to aid expansion. Muzzle velocity is given as 2,000 to 2,050 fps, depending upon reference, which would yield something over 2,400 foot-pounds (ft-lbs) of energy. Holland’s 1904 catalog also lists a 320-grain bullet “having a striking energy of 3,426 ft-lbs.” This would require a velocity of 2,200 fps – and a heavier rifle, according to H&H. That load didn’t last long.

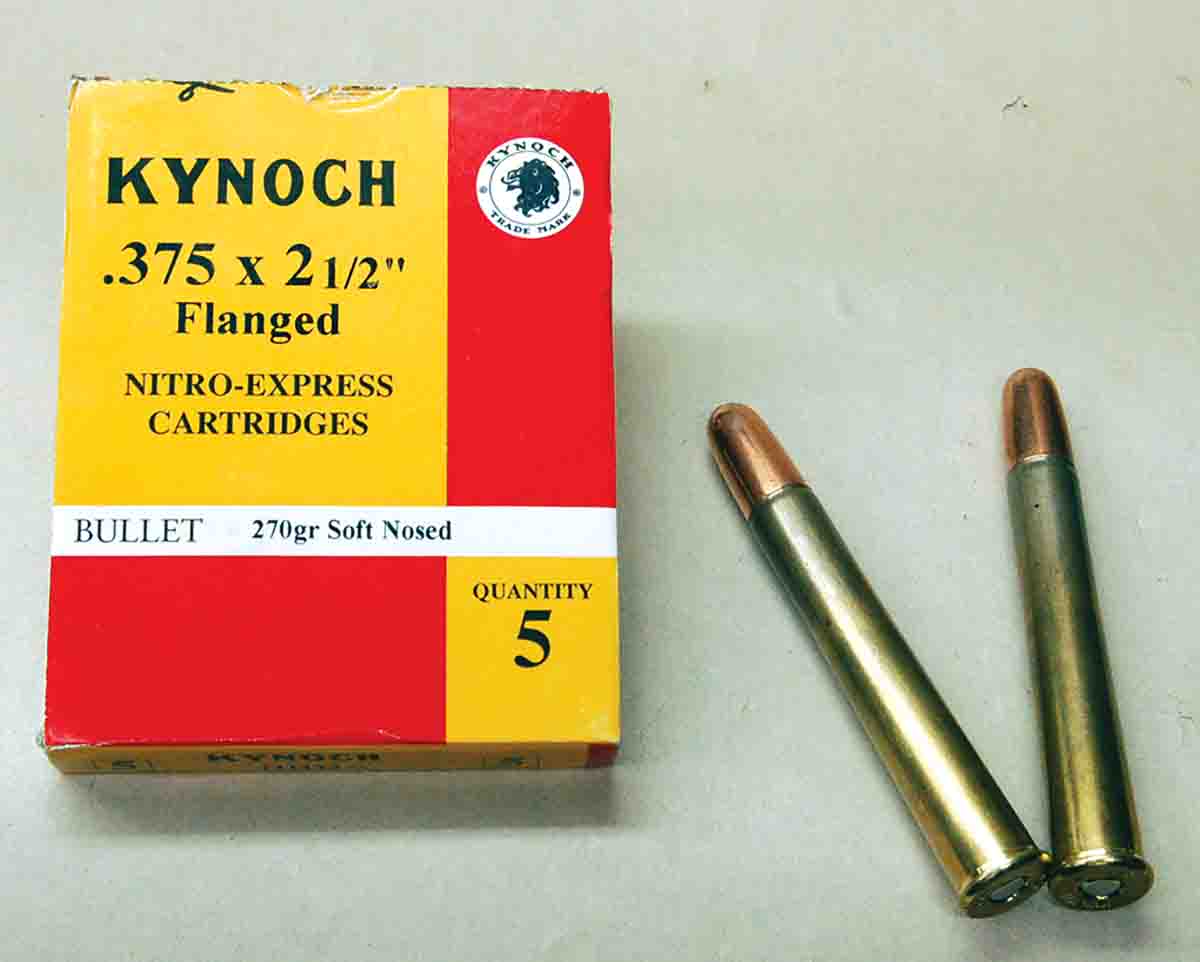

Eley and Kynoch loaded the round. By 1911, Kynoch listed 300- and 270-grain bullets loaded over 40 grains of cordite. Bullet types were softnose, pegged, solid, softnose split (jacket had narrow slits cut lengthwise in the bullet’s nose) and capped (basically a jacketed wadcutter with a hollow metal cap crimped on, forming a round nose). Kynoch ammunition was listed from 1903 to 1961.

H&H catalogs also state: “This .375 while possessing considerably increased stopping power, has all the advantages of the high velocity, flat trajectory and lightness of recoil characteristic of the .303 inch.” The velocity and trajectory may have been comparable to .303 loads at that time, but light recoil is questionable; the .375 Flanged NE (2½) was producing nearly 30 percent more energy than the .303.

Surprisingly, Holland & Holland offered the cartridge in a bolt rifle! Yes, H&H listed a Mannlicher that appears to be a Dutch or Romanian M95 military action (originally designed for the 6.5x53R) that had been rebarreled and stocked in typical British fashion. The same rifle was also available for the .303 and 6.5x53R cartridges. This was possible because loaded cartridge lengths of all three rounds were the same; so were case base and rim dimensions. There was probably no action modification necessary at all.

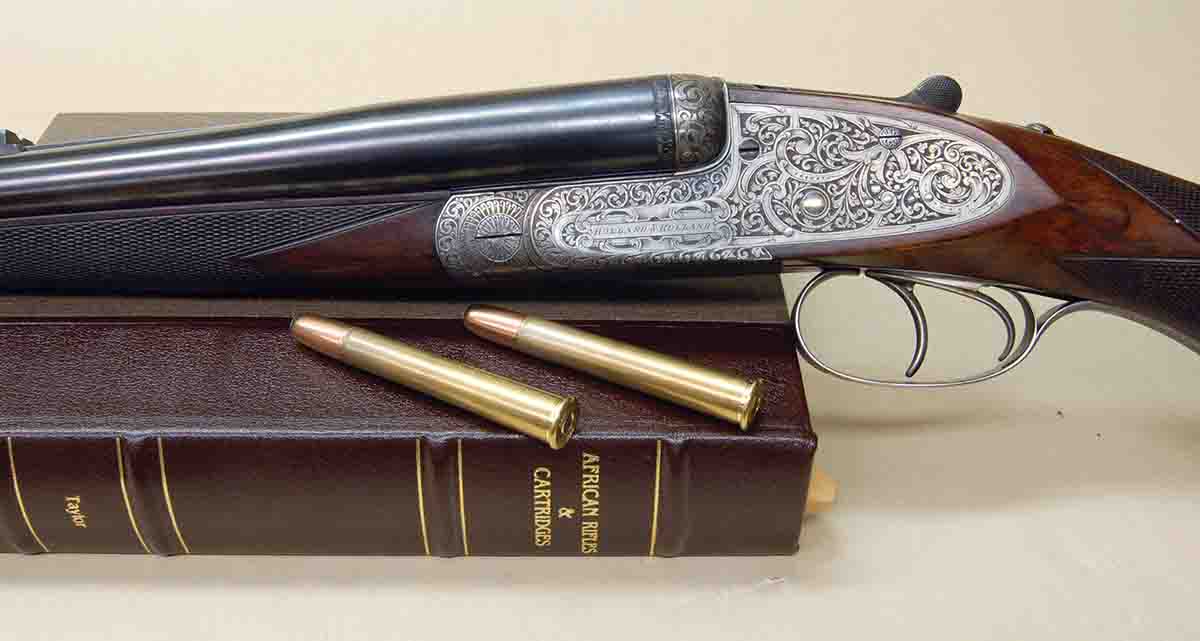

Holland & Holland also illustrated a falling-block, single shot and Martini single-shot sporting rifle chambering its new round. Yet the double rifle is what made the company’s reputation, and more specifically, the H&H Royal model. The one shown is courtesy of rifleman John Gannaway. At 9 pounds with 26-inch barrels, beautiful wood and incomparable Holland Royal engraving, it is an example of a beautiful object that begs to be used. Today that is easy to do, because Kynoch ammunition (Kynamco) yields right on 1,900 fps with a 270-grain bullet from this rifle. Recoil is like that of a 12-gauge shotgun firing 3¾ (dram equivalent), 1¼-ounce duck loads.

It is this use of the .375 Flanged NE (2½) that seems to be a mystery over the years. Even John Taylor of African Rifles and Cartridges fame didn’t get it. He said it was “not suitable for general African use, as it lacked power and penetration.” Well, yeah, as he was writing much later on when dozens of new cartridges were available, and smokeless powder was vastly improved over those in 1899. It’s like saying General Custer’s .45-70s were not suitable because the .30-06 was better.

The .375 Flanged NE (2½) was simply a cartridge of its time that – like anything more than 40 years old – is not understood today. Despite being what shooters now consider a large caliber, such was not the case up to at least 1920. There were plenty of more powerful rounds then-available in .45 caliber to 4 bore for delivering smashing power to large and dangerous animals. Our cartridge was never intended for such use.

Earlier observation that the cartridge was built on a lengthened .303 British case, but with an overall cartridge length the same as the .303, tells us what was really going on. By 1900, many hunters had been dashing about the world shooting all manner of creatures with the then-new small-bore, high-velocity rounds, all of which were of military origin. Such ammunition loaded with reliably expanding game bullets did not yet exist. Military rounds were everywhere but of course contained full-jacket, nonexpanding bullets. This ammunition did produce spectacular one-shot kills if animals were close enough – except when it didn’t! All too often the bullet went through with the quarry requiring a long follow-up or being lost entirely. Many British sportsmen became disillusioned with small-bullet, high-velocity cartridges.

Holland & Holland stepped in with the .375 Flanged NE (2½) using a bullet noticeably larger, heavier and more powerful than the new military rounds, yet its cartridge size was not much larger thanks to the efficiency of smokeless powder. The bullet expanded and held together. Some criticized the 2,000-fps muzzle velocity as too slow, not providing as flat a trajectory as the smaller calibers. True, yet it meant nothing, or very little, because 120 years ago most of the world’s hunting country was either jungle, heavy bush or thickly wooded, which is not true today. Shots much over 100 yards were rare, or at least unnecessary.

The cartridge became quite popular among experienced hunters, because it performed reliably on nondangerous game of up to 600 pounds or so. No doubt it was used on larger game, in which case the fast, second shot from a double rifle could generally settle things. Of course, stories of shooting lions, tigers and elephant are more interesting (salable) than shooting boar, tahr and stags, so one has to dig a bit to find records of its use. All accounts, however, indicate almost boring efficiency.

That popularity translates into original double and single-shot rifles being not too hard to find. Also, methinks a custom rifle on one of those old turnbolt Mannlichers would be a very interesting project. Such a rifle and cartridge would be just as efficient today for hunting in medium to dense cover as it was over 100 years ago.