Wildcat Cartridges

7MM JRS

column By: Richard Mann | December, 17

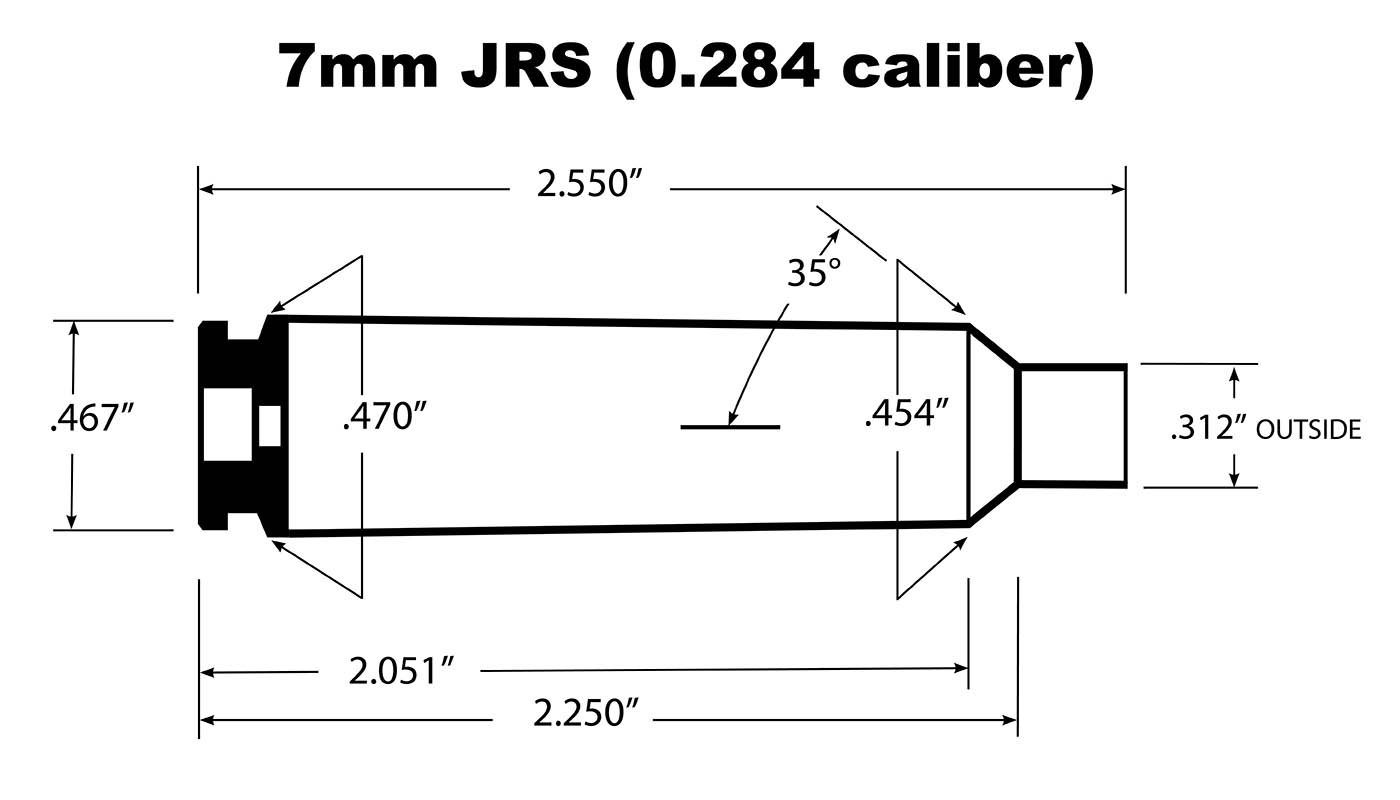

Sundra’s reasoning for the 7mm JRS – every wildcatter needs some rationale, real or imagined, to justify their obsession – was the fact that he disliked belted magnum cartridge cases. He also considered the roughly 82-grain water capacity of the 7mm Remington and Weatherby Magnums larger than optimum for the .284-inch bullet diameter. At the same time, he felt the 63-grain water capacity of the .280 Remington was less than ideal. These ideas lead to some work with the .280 Improved, but Sundra still felt there was a better answer.

It is unlikely there will ever be a wildcatter that gains fame through the creation of a cartridge, as Ned Roberts did with his .257. That does not mean the 7mm JRS is not a practical cartridge that still has value, even in this world of “short and fat” and 6.5mm hysteria. That’s why I was eager to work with it, specifically using propellants that were not available when the wildcat was created.

Sundra sent me a Winchester Model 70 with an E.R. Shaw barrel fitted to a Boyd’s laminated stock, along with some brass and instructions on case forming. There are two

The other method is to start with .30-06 brass and partially size the neck down with a 7mm JRS sizing die until resistance can be felt when closing the bolt. Again, pick a midrange .280 Remington load and fireform the case. The difference in using .280 Remington and .30-06 brass is that with .30-06 brass, the case neck will be formed about .045 inch shorter than the .30-inch neck length specified by Sundra.

I tried both methods, and both worked just as described; however, working with .280 Remington brass requires the extra step of expanding the neck to .30 caliber. Given that I had a good supply of Nosler .30-06 brass, I used it to save time and effort.

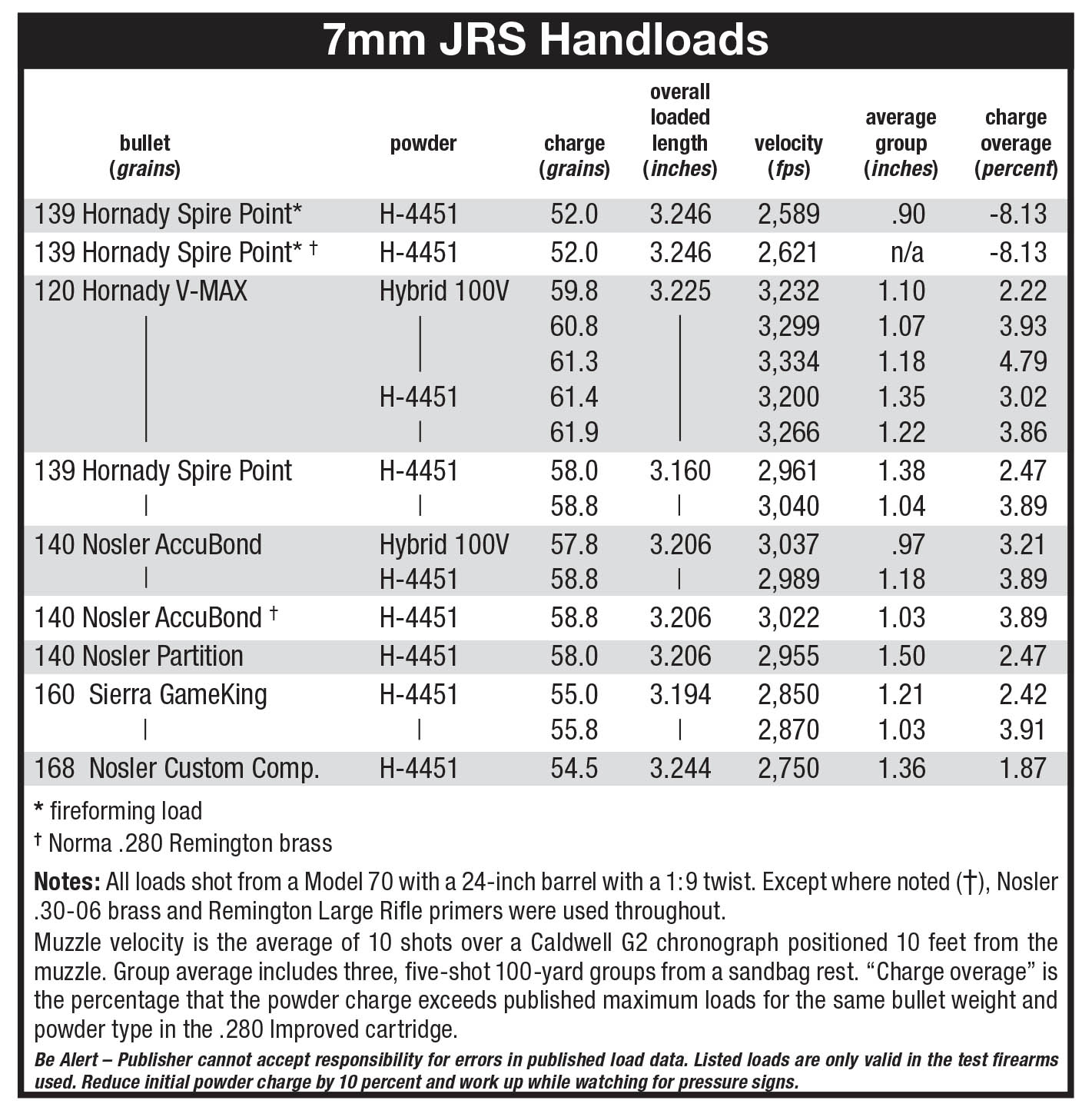

Sundra specified Reloader 22 as the ideal powder for the 7mm JRS, with H-4831, IMR-4831 and IMR-7828 being suitable too. I also tried IMR-4451 Enduron introduced in 2014, and Hybrid 100V. Both have a faster burn rate than RL-22 but are in the 4350 range. Without getting too aggressive, I wanted to see if I could approach 7mm Remington Magnum velocities. The question was where to start, and the answer was found with Hodgdon’s .280 Improved data.

Typical 7mm Remington Magnum handloads provide a velocity of around 3,330 fps with a 120-grain bullet. Using 61.3 grains of Hybrid 100V behind a Hornady 120-grain V-MAX delivered an average velocity of 3,334 fps. This load represents a 4.79 percent increase over the maximum powder charge for the .280 Improved. A Sierra 160-grain bullet provided 2,870 fps with 55.8 grains of IMR-4451. This powder charge is 3.91 percent above the maximum .280 Improved load and only falls short of 7mm Remington Magnum loads by 78 fps.

Accuracy with the rifle was rather good. Forty-two, five-shot groups were shot at 100 yards without cleaning the bore. The average group size for all loads fired was about 1.20 inches. Given the rifle’s snappy recoil, that is reasonably impressive. It should also be noted that because the brass used was formed with .30-06 cases, case necks were a bit shorter than Sundra’s specified ideal of .300 inch. Only one load was developed using the longer neck obtained with Norma .280 Remington brass. It shot groups a bit tighter than the .30-06-based loads, and it also showed a slight increase in velocity.

According to Hodgdon, the maximum 120- and 160-grain .280 Improved loads with Hybrid 100V and H-4451 produce velocities very similar to those I chronographed with the 7mm JRS. What this means is that there is room here to grow. If powder charges that were 6 percent larger than those listed as maximum for the .280 Improved were cautiously used for the 7mm JRS, then 7mm Remington Magnum performance might be exceeded. As stated earlier, I did not want to push the envelope, I wanted to see what I could do – conservatively – with the 7mm JRS using these new powders.

Admittedly, I’m not a 7mm kind of guy. I’m also not a “magnum” kind of guy, because I’ve never felt the need to deal with much recoil to kill a big-game animal. Regardless, with a rifle chambered for the 7mm JRS, there are only a few critters walking this planet that would seem too big to tackle.