Mike's Shootin' Shack

shooting The .50-98 WCF

column By: Mike Venturino | December, 17

Back in the 1870s, when cartridge-firing guns were practically new, Winchester was the pioneer of the repeating rifle concept. Starting with the Henry, then the Model 1866 firing rimfire .44s, Winchester advanced to reloadable centerfire cartridges with the Model 1873 .44 WCF (.44-40). Still, the company’s repeating leverguns lacked power. The rimfire .44 Henry, at maximum, was loaded with 28 grains of black powder, and the .44 WCF held only 12 grains more. Both cartridges used 200-grain bullets (some .44 Henry loads had bullets up to 218 grains).

Conversely, the big single-shot rifles by Sharps and Remington could take cartridges holding 90 to 100 grains of black powder, and depending on exact caliber, bullets weighed from 400 to 550 grains; it is obvious which rifle type hunters of game larger than deer would favor.

The Winchester Repeating Arms Company was nothing if not competitive, so by 1876 it super-sized (to use a modern term) the Model 1873 to take heftier cartridges. Initially, it used the .45-75 WCF with 350-grain bullets and a 75-grain powder charge. To accomplish such powder capacity and still have a cartridge short enough so a repeating rifle mechanism could accommodate it, case shape had to be bottlenecked.

Winchester’s sales expectations were not fulfilled with .45-caliber Model 1876s, so three years later the company literally expanded the concept to a .50-caliber cartridge. Whereas .45-75 WCF cases were 1.88 inches in length, the new .50 caliber was 1.94 inches. Bullet diameter increased from .457 inch to .508 inch, but bullet weight was decreased from 350 grains to 312 grains. The powder charge was increased a full 20 grains. With the increase in bullet diameter, the bottleneck shape of the case was all but eliminated; only a barely discernible taper remained.

This new round was the .50-95 WCF. For some reason, with .50-caliber Model 1876s, Winchester made its standard barrel length 26 inches, whereas all other cartridges were put in ’76s with 28-inch barrels. (Of course, special-order rifles could be had with almost any barrel length desired, out to 36 inches.) Its rifling twist rate was very slow. Because 312- grain, .50-caliber bullets are nearly as wide as they are long, a 1:60 twist was required.

In the late 1990s, Hank Williams Jr. loaned me an original Model 1876 .50-95 WCF to work up black-powder handloads for my book Shooting Lever Guns of the Old West (available from Wolfe Publishing). Bullets for that project were cast in NEI mould No. 510-300-GC, and brass was from Bertram of Australia. Dies were by RCBS. The NEI bullet actually weighed 314 grains when cast of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy and lubed with SPG. They were sized .509 inch, because the loaner Winchester’s barrel actually slugged .508 inch across its grooves. Eighty grains of GOEX FFg black powder fit in the Bertram cases, giving a velocity of 1,494 fps.

In my book, I ventured the opinion that Model 1876s would never be recreated for the replica market, but I was wrong – I’m glad I was. For in 2017 I was loaned one of the Cimarron/Uberti Model 1876 .50-95s to handload and shoot. In the intervening years, I had rid myself of .50-95 moulds, dies and brass. This time, a set of 4D/C-H dies was supplied along with a batch of Starline .50-90 brass that had been converted to .50-95 dimensions by Buffalo Arms Company (www.buffaloarms.com)

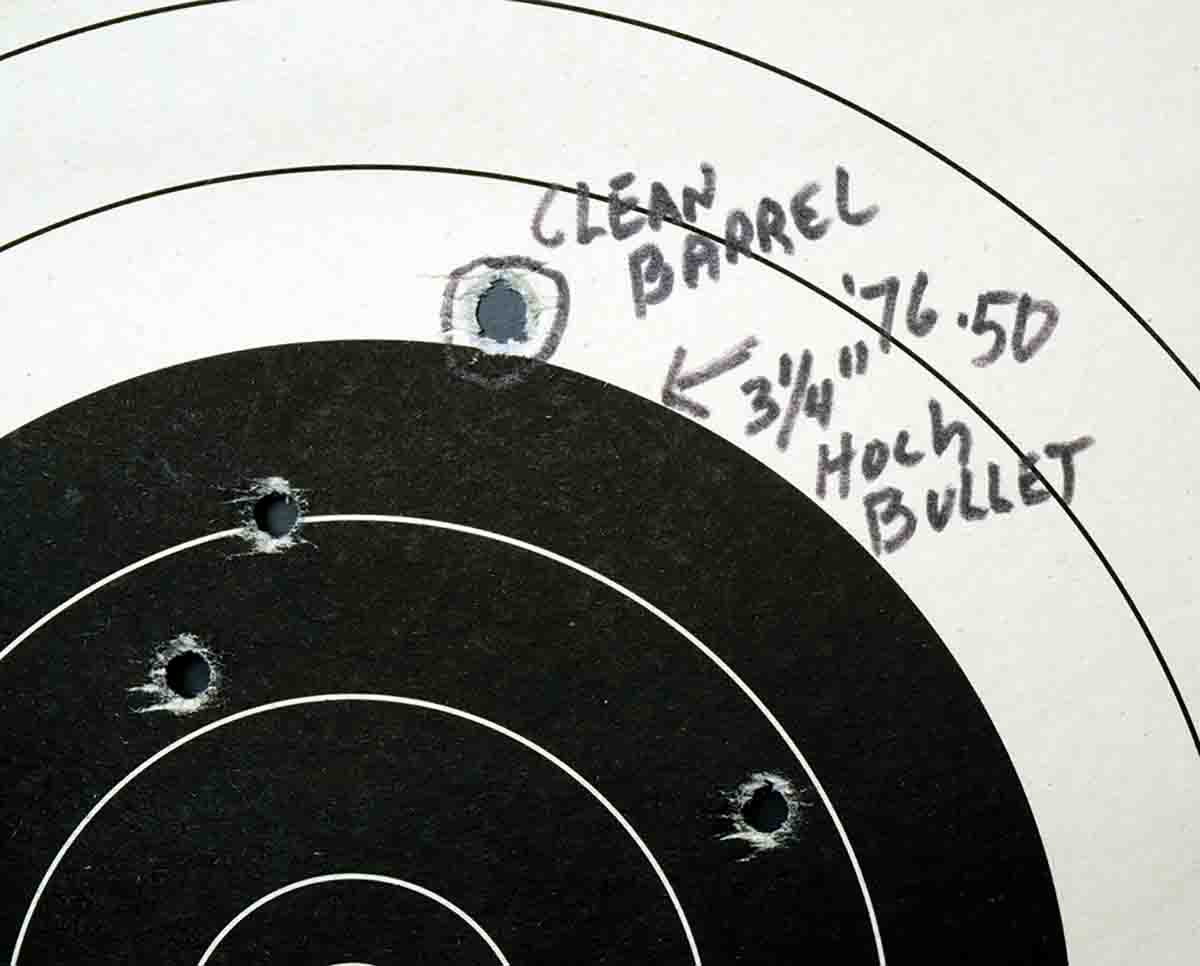

Also loaned was a vintage Ideal reloading tool with an integrated bullet mould. It was tried but found wanting, because bullets dropped from it were .518 inch. On hand was a Hoch mould for a .510-inch flatnose bullet. That design worked perfectly; cast of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy, they weighed 350 grains. Uberti’s handbook that accompanied the rifle indicated its barrel groove diameter was .507 inch, so I didn’t slug it. Bullets were sized .509 inch.

One difference in loading the second time was powder capacity. The converted Starline brass was thicker, consequently holding less black powder. Seventy-five grains of Swiss 11⁄2 Fg were all that could be loaded and still have room to seat bullets to an overall cartridge length of 2.25 inches. Even with heavier bullets and slightly less powder capacity, loads still generated 1,375 fps from the Cimarron/Uberti’s 28-inch barrel.

Shooting these .50-caliber Model 1876s is an experience. Smoke billows out 15 or 20 feet. Muzzle blast is tremendous, and that crescent buttplate called for a shoulder pad even for casual shooting.