6mm Creedmoor

Loads for a Higher-Pressure Cartridge

feature By: John Barsness | December, 18

The 6mm Creedmoor appeared due to Remington’s 1947 introduction of the first commercially successful “short-action” bolt rifle. The company’s Model 722 happened to have a magazine 2.85 inches long, give or take a couple hundredths. Back then, very few “short-action” cartridges existed; the 722 was originally chambered for only two, the .257 Roberts and .300 Savage.

Along with its “long-action” companion rifle, the Model 721, the Remington 722 became very popular. Within a decade, Remington also chambered the 722 in .222 Remington, .222 Remington Magnum, .244

In 1962 the 722 and 721 morphed into the Remington 700, which soon became the most popular bolt rifle in the country – if not the world. The short-action 700 essentially standardized the length of the modern short bolt-action magazine at 2.85 inches.

However, most American target shooters remained convinced that .30-caliber cartridges from the .30-06 up were needed for shooting at 1,000-yard targets. “Everybody” knew heavier .30-caliber bullets drifted less in the wind, and smaller cartridges did not drive them fast enough.

Some short-range benchrest shooters, however, tried the .308 Winchester because its bullets drifted less than those of the popular .222 Remington, then the leading 100-200 yard benchrest cartridge. Eventually, however, they realized the .308 kicked too much for consistently fine shooting, even in rifles weighing more than 10 pounds.

It took far longer for America’s long-range target shooters to come to the same basic conclusion about larger .30-caliber cartridges. This finally occurred as they realized bullet weight was not the big factor in wind drift, but ballistic coefficient (BC).

After the .30-caliber obsession started dissipating, Americans “discovered” what many European target shooters had known for decades: A 6.5mm boat-tail spitzer of around 140 grains drifts similarly to a 190-grain .30-caliber boat-tail spitzer started at the same velocity – but the lighter bullet results in lighter recoil, allowing shooters to avoid flinching.

Now, there are limits to this because smaller calibers limit the length – and hence BC – of bullets. Target-shooting distances keep increasing due to laser rangefinders and other modern technology, and calibers even larger than .30 have proven best for shooting at a mile or more. At ranges out to around 1,000 yards, however, cartridges smaller than .30 caliber now rule target shooting.

Consequently, 6.5mm wildcats with slightly shorter cases were designed to fit perfectly in 2.85-inch magazines. Several commercial cartridges eventually appeared to fill this demand, including 2005’s 6.5x47 Lapua and 2007’s 6.5 Creedmoor.

Yet many target shooters proved even pickier, soon “discovering” 6mm cartridges recoil even less than 6.5mm cartridges due to lighter bullets. As a result of this startling news, “short” 6mm wildcats started appearing, among them (naturally) the 6mm Creedmoor, the 6.5 Creedmoor necked down.

According to various sources, at least two shooters had a major hand in getting Hornady to produce the 6mm Creedmoor

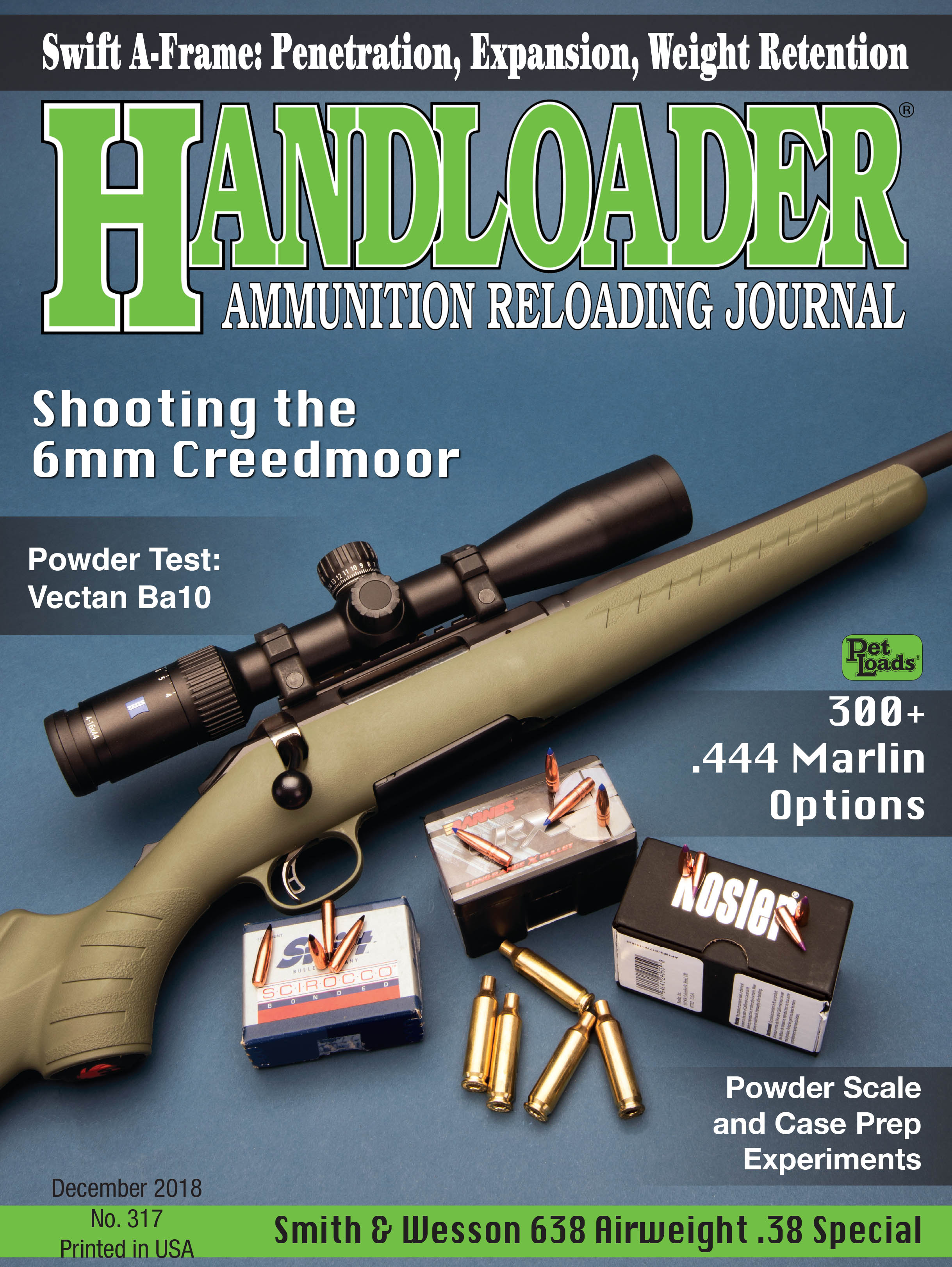

Hornady started producing 6mm Creedmoor ammunition and cases in 2017. Soon afterward I acquired a slightly used Ruger American Rifle (RAR) 6mm Creedmoor owned by a hunter who thought it simply had to be more accurate than his .243 Winchester. It was not, so he listed the 6mm Creedmoor on the Internet for an even lower price than a new RAR.

This Predator version has a slightly heavier barrel than the standard sporter. Immediately after opening the box, I grabbed the tip of the forend and the barrel in my right hand, and found that the forend could be easily pressed against the barrel. This meant it was not truly free floated, a probable cause of the unsatisfactory accuracy. (The stiffer forends on newer RAR stocks usually prevent this, but not always).

Not so astoundingly, a nearby sporting goods store had Hornady 6mm Creedmoor brass for sale, but no dies could be found locally, so I obtained a set of Redding Match Dies. While waiting for them, I performed a “literature search” of published 6mm Creedmoor data and found plenty, not just from Hornady but from Hodgdon, Sierra and Speer. In fact, by mid-2018 far more pressure-tested data existed for the 6mm Creedmoor than many other recently introduced factory rounds, probably due to its popularity as a wildcat.

The Hornady brass proved very consistent in weight and neck thickness. After running all the necks over the expander ball in the Redding sizing die, case length measured slightly less than the maximum 1.920 inches listed by Hornady, so I chamfered all the case mouths.

The chamber throat was investigated using both a Hawkeye borescope and by seating different bullets. The lands in front of the chamber were cut pretty evenly for a factory rifle, with a relatively gentle angle, which is common on target rifles but not hunting rifles. The longest any bullet could be seated just short of the lands was 2.865 inches when using the Hornady 108-grain ELD-M. Whether through luck or design, the inside length of the magazine on this particular Predator measures 2.870 inches; most other bullets ended up seated to an overall length of 2.600 to 2.800 inches.

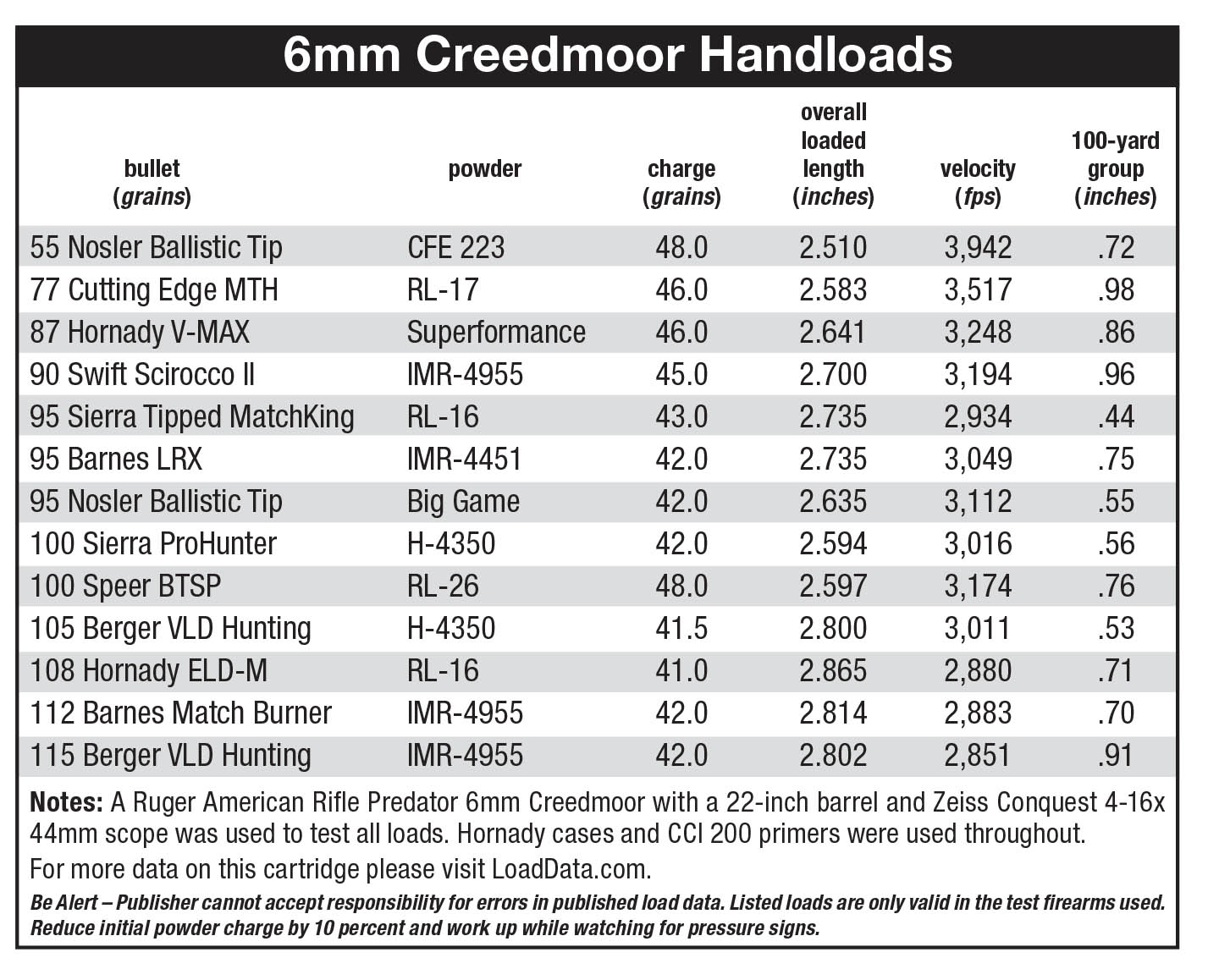

Generally, I start range-testing cartridges larger than .22 caliber with three-shot groups, then retest with four-shot groups, often changing seating depth slightly if the three-shot groups seemed iffy. The 6mm Creedmoor loads were primarily picked from data listing the highest velocity, but only a few required a little adjustment after the three-shot tests to shoot under an inch, and eventually all averaged under that magic number.

While the 6mm Creedmoor is obviously designed for longer, high-BC bullets, some lighter bullets were tested for those shooters preferring screaming muzzle velocities – though one of these, the Cutting Edge 77-grain Match/Tactical/Hunting (MTH) is an all-copper, hollowpoint boat-tail that is very long for its weight. The front end is designed to disintegrate, not just expand, and at 3,500 fps shoots very flat at “normal” hunting ranges out to 500 yards. Both my wife and I have had excellent field results with other Cutting Edge hunting bullets that also lose their “petals.”

One obvious question is whether the 6mm Creedmoor will become as popular as the 6.5 Creedmoor, the latter swiftly becoming one of the “standard” cartridges offered by just about every manufacturer of bolt action rifles. This standard list has long included the .223 Remington, .22-250 Remington, .243 Winchester, .270 Winchester, 7mm Remington Magnum, .308 Winchester, .30-06 and .300 Winchester Magnum. While many cartridges exist between the .243 and .270, apparently a lot of shooters feel the 6.5 Creedmoor plugs that gap pretty well, with recoil similar to the .243 but with bullet weights edging closer to the .270’s weights.

In contrast, the 6mm Creedmoor offers just about the same ballistics as the .243, a very popular hunting cartridge not only in the U.S. but also in Europe and Africa. The 6mm Creedmoor’s advantages over the .243 are pretty insignificant and mostly apply to long-range target shooting.

Quite a few target shooters tried the .243 Winchester during the rush to smaller calibers, including David Tubb, 11-time national High Power champion. Aside from the same problem encountered with the .260 Remington and longer, high-BC bullets in 2.850-inch magazines, the .243’s relatively shallow shoulder angle of 20 degrees tends to funnel hot powder gas right in front of the short neck, accelerating throat erosion and resulting in relatively short barrel life.

The 6mm Creedmoor solves the overall length problem, and it also extends barrel life somewhat, due to its modern “accuracy” shoulder angle of 30 degrees and a slightly longer neck. Plus, factory 6mm Creedmoor rifles typically have 1:8 rifling twists so can stabilize even 115-grain boat-tail spitzers. The twists of most factory .243 Winchesters are either the long-standard 1:10, or occasionally 1:9 – not quite enough to stabilize really long bullets under all environmental conditions.

After my first range session provided some fired brass, the water capacity of the 6mm Creedmoor and .243 Winchester was measured with a Berger 105-grain VLD Hunting bullet seated to an overall length of 2.800 inches. (Measuring water capacity to the top of the neck often provides an inaccurate comparison between cartridges. Necks can vary considerably in length, yet in big-game or long-range target rounds extra neck length does not usually add to powder capacity, as they are normally filled by bullets, not powder.)

Fired brass is also preferable because the fired primers seal the flash holes, necks are expanded enough to allow a bullet to just slip-fit inside, and case dimensions reflect capacity more accurately than new brass. For consistency, I also used Hornady .243 brass along with some Winchester brass on hand, which weighed just about the same. The 6mm Creedmoor cases had an average water capacity of 49.2 grains, and the .243 Winchester cases held 49.6 grains, just about the same. However, the SAAMI maximum average pressure for the 6mm is 62,000 psi and 60,000 psi for the .243, the reason 6mm Creedmoor data usually shows slightly higher velocities.After several range sessions, another very slight advantage for the 6mm Creedmoor was discovered: Cases stretch less than .243 brass, no doubt due to the steeper shoulder of the Creedmoor. The .243 is known for requiring rather frequent trimming, and hence short case life. Like shorter barrel life, that doesn’t matter to most hunters but does to target shooters.

So, will zillions of shooters rush out to replace their .243 Winchesters with 6mm Creedmoors? Some will, partly because long-range target shooting drives much of the recent rifle market, even among hunters, many of whom simply must have the latest advances in rifles, cartridges and scopes.

One example is the Ruger Precision Rifle, essentially a target version of the Ruger American Rifle, often purchased by hunters looking for long-range performance. Less than two years ago, I reviewed a Precision Rifle .243 Winchester in Rifle as part of an article on “chassis” rifles. It shot extremely well, even with Winchester hunting ammunition, but today Ruger no longer lists the .243 in the Precision Rifle, instead chambering the 6mm Creedmoor.

However, the .243 Winchester still appears in the list of chamberings for the RAR, and just about every other bolt-action rifle made on Earth – and will for a very long time. Meanwhile, hunters who feel an extreme itch for accuracy may find that the 6mm Creedmoor scratches it.